Whooping crane facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Whooping crane |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| In the Calgary Zoo, Alberta | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Gruiformes |

| Family: | Gruidae |

| Genus: | Grus |

| Species: |

G. americana

|

| Binomial name | |

| Grus americana (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

|

|

|

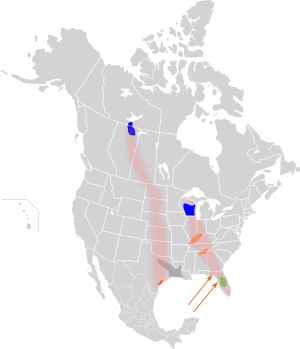

| Distribution map of the whooping crane. blue: breeding, orange: wintering, green: year-round, grey: experimental year-round | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Ardea americana Linnaeus, 1758 |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The whooping crane (Grus americana) is a fascinating bird native to North America. It gets its name from the loud, trumpet-like calls it makes, which sound like "whoops." These calls can travel for miles! Along with the Sandhill Crane, it is one of only two types of cranes found in North America. The Whooping Crane is also the tallest bird on the continent.

These magnificent birds have a long lifespan, often living for 22 to 24 years in the wild. However, their journey has been difficult. A long time ago, there were many more Whooping Cranes, but because of too much hunting and losing the places where they lived, their numbers dropped dramatically. By 1941, there were only 21 Whooping Cranes left in the wild and just two living in special care. Thanks to dedicated conservation efforts over many decades, their population has slowly grown. As of 2020, the total number of Whooping Cranes, including those in the wild and those in captivity, was a little over 911 birds. This shows that while they are still rare, the efforts to save them are making a difference.

Contents

What They Look Like

Adult Whooping Cranes are mostly white, which makes them easy to spot. They have a bright red patch on the top of their head (called a crown) and a long, dark, pointed beak. When they are young, they look a bit different, with feathers that are more cinnamon brown.

When a Whooping Crane flies, you can see its long neck stretched out straight and its long, dark legs trailing behind. A key feature visible in flight is the black tips on their wings.

Whooping Cranes are very large birds. They are the tallest birds in North America, standing between 4 feet 1 inch and 5 feet 3 inches tall. They are also one of the heaviest birds on the continent. On average, male Whooping Cranes weigh about 16 pounds, while females weigh about 14 pounds. Their wingspan, the distance from the tip of one wing to the tip of the other when fully spread, is usually between 6 feet 7 inches and 7 feet 7 inches.

It's important not to confuse Whooping Cranes with other large white birds in North America, like the Great Egret or the Wood Stork. While these birds are also white and have long legs, they are much smaller than the Whooping Crane. Even some large Sandhill Cranes can be similar in size, but Sandhill Cranes are gray, not white, so they are easy to tell apart.

How they communicate

Whooping Cranes use their loud calls to communicate. They have "guard calls" to warn their partner about possible danger. Mated pairs also perform a special rhythmic call together, called a "unison call," often in the morning, after courtship dances, or when protecting their territory.

Where They Live

A long time ago, Whooping Cranes lived across a large area in the middle of North America, stretching south into Mexico. But as their numbers decreased, their range shrank.

Today, the main wild population of Whooping Cranes breeds in a remote area called the muskeg (a type of swampy forest) in Wood Buffalo National Park, which is located in Alberta and the Northwest Territories in Canada. This area is the last remaining place where the original wild Whooping Cranes nest in the summer.

In the winter, this main population of Whooping Cranes flies south. Their winter home is along the coast of Texas, near the town of Rockport, especially in the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge and nearby areas like Matagorda Island and the Lamar Peninsula.

Scientists and conservationists have also been working to create new populations of Whooping Cranes in other areas. For example, Whooping Cranes have nested naturally in central Wisconsin for the first time in 100 years as part of a reintroduction project. These birds now spend their summers in Wisconsin and nearby states. There are also experimental populations that do not migrate, which have been introduced in Florida and Louisiana.

During their long migration between Canada and Texas, Whooping Cranes often stop at places like the Salt Plains National Wildlife Refuge in Oklahoma. This refuge is a very important resting and feeding spot for the migrating cranes.

Reproduction and parenting

Whooping Cranes build their nests on the ground, usually in a slightly raised spot within a marshy area. The female crane typically lays one or two eggs, usually in late April or mid-May. The eggs are olive-colored with blotches and are about 2½ inches wide and 4 inches long, weighing around 6.7 ounces. Both parents take turns sitting on the eggs to keep them warm, which takes about 29 to 31 days. Usually, only one chick from a nest survives to grow up. The parents take care of the young bird for 6 to 8 months, and the young crane stays with its parents for about a year.

What They Eat

Whooping Cranes are omnivores, which means they eat both plants and animals. They usually look for food while walking in shallow water or in fields, sometimes using their long beaks to probe into the mud or ground.

While they eat a variety of things, they tend to eat more animal matter than many other types of cranes. In their winter homes in Texas, they eat things like crabs, clams, grasshoppers, fish (like eels), small reptiles (like snakes), mice, voles, water plants, acorns, and berries.

In the summer, when they are breeding, their diet can include frogs, snakes, small rodents, small birds, fish (like minnows), water insects, crayfish, clams, snails, and berries. Studies have shown that blue crabs are a very important food source for the cranes wintering in Texas, sometimes making up a large part of what they eat.

When they are migrating, Whooping Cranes also eat waste grain left in fields, such as wheat, barley, and corn.

Predators

While adult Whooping Cranes are very large and don't have many natural enemies, their eggs and young chicks are vulnerable to predators. Animals that might try to eat their eggs or chicks include black bears, wolverines, gray wolves, cougars, red foxes, Canada lynx, bald eagles, and common ravens. Golden eagles have also been known to kill young Whooping Cranes.

Adult Whooping Cranes are usually able to defend themselves or avoid medium-sized predators like coyotes if they are aware of the danger. However, in areas where new populations have been introduced, especially birds raised in captivity, they might not be as good at avoiding predators. For example, in Florida, bobcats have been a significant threat to Whooping Cranes, including adults. Scientists believe this might be partly because there are fewer large predators that would normally hunt bobcats in those areas.

Sadly, another threat to Whooping Cranes, especially in reintroduced populations, has been illegal hunting by people. Even though it is against the law and there are consequences, some cranes have been shot. This is a major problem because every single Whooping Crane is important for the survival of the species.

Conservation Efforts

Whooping Cranes were likely never extremely common, but their population dropped dramatically due to people hunting them without rules and destroying the wetlands and grasslands where they lived. Before Europeans settled widely in North America, there were likely over 10,000 Whooping Cranes. By 1870, that number had fallen to about 1,300-1,400. The situation became critical by 1938, with only 15 adult birds left in the main migratory flock and a small non-migratory group in Louisiana. A hurricane in 1940 further reduced the Louisiana population.

Saving the Whooping Crane became a major focus for conservationists. In the early 1960s, people like Robert Porter Allen worked to educate the public, especially farmers and hunters, about the importance of protecting these birds. Organizations like the Whooping Crane Conservation Association were formed to influence government decisions and raise awareness. The Whooping Crane was officially declared endangered in 1967, which provided legal protection.

Early efforts included trying to breed Whooping Cranes in captivity. This was challenging at first. A female crane named Josephine, who was injured and brought into care in 1940, was part of these early attempts. While she produced eggs, getting the chicks to survive and then reproduce themselves was very difficult for many years.

Meanwhile, the wild population was growing very slowly. This led to discussions among conservationists about the best way forward: should they focus only on protecting the few wild birds, or should they try harder with captive breeding, even if it meant taking birds or eggs from the small wild population?

A key discovery happened in 1954 when the summer breeding grounds in Wood Buffalo National Park were finally located. Scientists observed that Whooping Crane pairs often laid two eggs but usually only raised one chick successfully. This led to the idea of taking one egg from a two-egg nest in the wild. The hope was that the wild parents could still successfully raise one chick, while the second egg could be used to start a captive breeding program. This strategy was tried and seemed to work without harming the wild population's ability to reproduce.

Eggs taken from the wild were sent to places like the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Maryland. Here, scientists developed techniques for hatching and raising crane chicks in captivity, often practicing with the more common Sandhill Cranes first. Getting these captive-raised birds to reproduce was still a hurdle.

In the 1970s, ornithologist George W. Archibald worked closely with a female Whooping Crane named Tex at the International Crane Foundation. He spent years trying to encourage her to lay a fertile egg. This dedicated effort led to the hatching of a chick named Gee Whiz, who successfully grew up and reproduced with other Whooping Cranes.

The techniques developed at places like Patuxent and the International Crane Foundation were crucial for creating successful captive breeding programs. These programs provided the birds needed for reintroduction efforts. A single male crane named Canus, who was rescued as an injured chick in 1964, became a very important bird in the captive breeding program, fathering or grand-fathering many captive-bred cranes.

More recently, in 2017, the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center decided to end its Whooping Crane breeding program after over 50 years. Their birds were moved to other zoos and conservation centers to continue the breeding efforts. This move caused some concern about how it might affect the overall program.

Despite challenges, the wild population has been increasing. In 2007, the Canadian Wildlife Service counted 266 birds in Wood Buffalo National Park. By early 2017, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimated that 505 Whooping Cranes had arrived at the Texas wintering grounds. As of 2020, there were an estimated 677 Whooping Cranes living in the wild across the original migratory population and three reintroduced populations, with another 177 birds in captivity. This brought the total population to over 800 birds.

Protecting the winter habitat in Texas is also very important. Environmental groups have worked to ensure that the cranes have enough water, especially during droughts, by taking legal action to protect river flows that feed their marshy habitat. Conservation groups have also been buying land and protecting areas near the Aransas refuge to provide more safe places for the growing population. Money from the settlement of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill has even helped fund some of these land purchases.

Scientists are also thinking about how climate change might affect the cranes' migration and breeding cycles in the future.

Reintroduction Efforts

Besides protecting the original wild population, several projects have tried to create new populations of Whooping Cranes in other areas.

One early project, started in 1975, tried a method called "cross-fostering." Scientists placed Whooping Crane eggs into the nests of Sandhill Cranes in Idaho. The idea was that the Sandhill Cranes would raise the Whooping Crane chicks, and the chicks would learn the migration route from Idaho to New Mexico by following their foster parents. While many chicks hatched and learned to migrate, they imprinted on the Sandhill Cranes, meaning they saw themselves as Sandhill Cranes and didn't try to mate with other Whooping Cranes. This project was stopped in 1989 because it didn't lead to a self-sustaining population.

Another effort began in 1993 to create a population that would not migrate, near Kissimmee, Florida. Captive-bred birds were released into the wild. While this population did produce the first chick conceived in the wild by reintroduced cranes in 2003, the birds faced high death rates and didn't reproduce very successfully. Releases were stopped in 2005, and the population slowly decreased. By March 2018, only 14 cranes remained. Some of the surviving birds have since been moved to join a newer reintroduction effort in Louisiana. As of 2020, only 9 birds were left in the Florida population.

A third major reintroduction project started in 2001 to create a new migratory population east of the Mississippi River. This project used a unique method: young Whooping Cranes were raised by humans wearing crane costumes to prevent them from imprinting on people. These chicks were then trained to follow a special ultralight aircraft, which led them on their first migration from Wisconsin to Florida. Once they learned the route, they were expected to migrate on their own in future years. This project was managed by organizations like Operation Migration and the Whooping Crane Eastern Partnership. As the population grew, they also started releasing captive-raised juveniles directly into the wild flock, hoping they would learn the migration route from the older cranes.

This Eastern Migratory Population has faced challenges, including severe weather events like tornadoes that killed several birds in 2007. Sadly, illegal shootings have also been a significant problem for this population. Despite these setbacks, the population has grown. In May 2011, there were 105 birds, and by June 2018, the estimate was 102 birds. However, the number had dropped to 86 birds in 2020. Due to challenges with the hand-raised birds reproducing, the ultralight-led migration program was discontinued in 2016, with focus shifting to other release methods.

More recently, a new effort began in 2011 to establish a non-migratory population in Louisiana, where a historical population once lived. This project is a partnership between several government agencies and conservation groups. Captive-bred cranes are released into the White Lake Wetlands Conservation Area. This population has also faced challenges, including illegal shootings. However, there have been successes. In April 2016, a pair of reintroduced cranes successfully hatched and raised a chick, the first born in the wild in Louisiana since 1939. Scientists have also tried swapping eggs from captive birds into wild nests in Louisiana, allowing wild cranes to raise the chicks. As of August 2018, at least 65 birds were surviving in this population, and by 2020, the number had reached 76 birds, including birds moved from the Florida project.

Illegal hunting remains a serious threat to these reintroduced populations. It is estimated that a significant percentage of deaths in both the Eastern Migratory Population and the Louisiana population have been caused by illegal shootings. People caught for these actions have faced consequences under the law. Conservation groups emphasize that the cost and effort to raise and release a single Whooping Crane are very high, making every loss to illegal activity particularly damaging to the recovery efforts.

Despite the challenges, the story of the Whooping Crane is one of hope and dedicated effort. Thanks to the hard work of many people and organizations, this magnificent bird is slowly making a comeback from the edge of extinction.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Grulla trompetera para niños

In Spanish: Grulla trompetera para niños

- Puppet-rearing

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |