Wilhelm Dörpfeld facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Wilhelm Dörpfeld

|

|

|---|---|

Wilhelm Dörpfeld

|

|

| Born | 26 December 1853 Barmen, Prussia

|

| Died | 25 April 1940 (aged 86) |

| Nationality | German |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Archaeology |

Wilhelm Dörpfeld (born December 26, 1853 – died April 25, 1940) was a German architect and archaeologist. He was a pioneer in a special way of digging up old sites called stratigraphic excavation. This means he carefully studied the different layers of soil to understand when things were built or used. He also made very detailed drawings of his archaeological finds.

Dörpfeld is famous for his work at Bronze Age sites around the Mediterranean Sea. These include places like Tiryns and Hisarlik, which is believed to be the ancient city of Troy. He continued the excavations started by Heinrich Schliemann at Troy. Like Schliemann, Dörpfeld believed that the places mentioned in the ancient Greek poems by Homer were real. Even though some of his exact ideas about these locations aren't fully accepted today, his main idea that they were real places is now widely agreed upon. His work helped develop new scientific ways to study these important historical sites. It also made more people interested in the culture and mythology of Ancient Greece.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Wilhelm Dörpfeld was born in Barmen, which was then part of Prussia. His parents were Christine and Friedrich Wilhelm Dörpfeld. His father was a well-known teacher and a strong Christian. He wanted his family to have deep religious feelings.

Because of this, Dörpfeld went to religious schools. There, he learned the basics of Latin and Greek. He finished high school in Barmen in 1872.

Career in Archaeology

In 1873, Dörpfeld began studying architecture in Berlin at the famous Academy of Architecture. At the same time, he started working for an industrial company. His sister, Anna, helped him pay for his studies because his father could not. During school breaks, Dörpfeld worked for a railway company, drawing buildings and other architectural designs. He graduated with honors in 1876.

Working at Ancient Olympia

In 1877, Dörpfeld became an assistant at the excavations in Ancient Olympia, Greece. He worked with famous archaeologists like Richard Bohn and Ernst Curtius. Later, he became the technical manager of the project. The team found many amazing things, including a complete statue of Hermes made by the artist Praxiteles. These excavations helped people remember the ancient Olympic Games. They also played a part in starting the modern Olympic Games in 1896.

Meeting Heinrich Schliemann

After returning from Olympia, Dörpfeld planned to take his architecture exam and settle down in Berlin. He needed a steady job because he was preparing to start a family. In February 1883, he married Anne Adler, who was the daughter of his university professor, Friedrich Adler. They had three children together. Around this time, he met Heinrich Schliemann, a famous archaeologist. Schliemann convinced Dörpfeld to join his archaeological trips.

Excavations at Troy and Other Sites

In 1882, Dörpfeld and a team of archaeologists joined Schliemann, who was digging at Troy. The two became good friends and worked together on other projects too. They dug at Tiryns from 1884 to 1885. They also returned to Troy from 1888 to 1890.

Dörpfeld also worked at the Acropolis of Athens from 1885 to 1890. There, he uncovered the Hekatompedon temple, which was an older version of the Parthenon. He continued excavations at Pergamon (from 1900 to 1913) and in 1931 at the Agora of Athens.

In 1886, Dörpfeld helped start the German School of Athens. This school was later named the Dörpfeld Gymnasium in his honor. From 1887 to 1912, he was the director of the German Archaeological Institute at Athens. In 1896, he published a book called Das griechische Theater. This was the first major study of how Greek theatres were built.

After he retired in 1912, Dörpfeld took part in many discussions about archaeology. For example, in the 1930s, he debated with American archaeologist William Bell Dinsmoor about the different stages of the Parthenon's construction. In the early 1920s, he started teaching at the University of Jena. However, he didn't enjoy teaching much, so he returned to Greece.

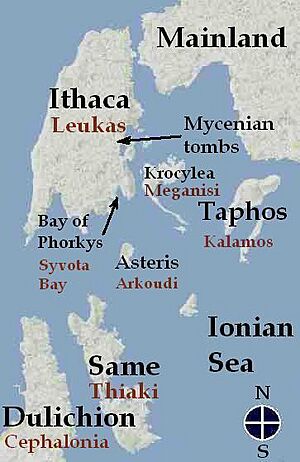

Dörpfeld passed away in 1940 on the island of Lefkada, Greece. He owned a house there. He believed that the bay of Nidri on Lefkada's eastern coast was the real Ithaca, the home of Odysseus from Homer's Odyssey.

Archaeological Discoveries and Methods

Dörpfeld developed a very important method for dating archaeological sites. He looked at the layers of soil (called strata) where objects were found. He also studied the types of materials used to build structures. This helped him figure out how old a site was.

He corrected many of Schliemann's earlier ideas. For example, at Mycenae, Schliemann thought some burial sites were the "Treasury of Atreus." Dörpfeld realized they were actually "tholos" tombs, which are round, beehive-shaped tombs.

The Acropolis of Athens

During excavations on the Acropolis of Athens, Dörpfeld helped correct a long-held belief. People used to think that the temple of Athena, which was destroyed by the Persians in 480 BCE, was located under the Parthenon. Dörpfeld showed that it was actually to the north of the Parthenon. He suggested that three different temples were built in the same spot over time. He called them Parthenon I, Parthenon II, and Parthenon III (which is the temple we see today). He was even able to figure out the size and shape of the first two proto-Parthenons.

Troy and Homer's Ithaca

After Schliemann died in 1890, his wife hired Dörpfeld to continue the excavations at Troy. Dörpfeld found nine different cities built one on top of the other at the Hisarlik site. He believed that the sixth city was the legendary Troy from Homer's stories. This city was larger than the first five and had tall limestone walls. Dörpfeld also found Mycenaean pottery in the same layers, which supported his idea. However, most modern archaeologists now think that Homer's Troy was actually the seventh city layer.

Dörpfeld spent a lot of time trying to prove that Homer's epic poems were based on real historical events. He suggested that the bay of Nidri, on the eastern coast of Lefkada, was Odysseus's home, Ithaca. Dörpfeld compared parts of the Odyssey to the actual geography of Lefkada. He concluded that it must be the Ithaca described by Homer. He was especially convinced by this passage:

- I dwell in shining Ithaca. There is a mountain there,

- high Neriton, covered in forests. Many islands

- lie around it, very close to each other,

- Doulichion, Same, and wooded Zacynthos—

- but low-lying Ithaca is farthest out to sea,

- towards the sunset, and the others are apart, towards the dawn and sun.

- It is rough, but it raises good men." Homer, Odyssey 9.1:

Today, Lefkada is connected to mainland Greece by a causeway and a floating bridge. But in ancient times, it was connected by a narrow strip of land, making it more like a peninsula than an island. This strip of land was cut through by the Corinthians in the 7th century BCE. However, modern geographers say that ancient Lefkada was indeed an island. They note that the causeway we see today is new, formed by dirt building up in the channel. So, Lefkada might have been connected to the mainland in different ways over thousands of years. Dörpfeld might have thought that Lefkada was a separate island when Homer wrote about it.

Legacy

Wilhelm Dörpfeld was a very important person in the study of classical archaeology. His method of dating archaeological sites by looking at the layers of soil and building materials is still a main part of how archaeologists study sites today.

However, his excavations did have some problems. His strong desire to prove that Homer's Odyssey was based on real places was seen as a bit romantic by some. Other archaeologists pointed out that he focused too much on buildings when dating sites. He sometimes didn't pay enough attention to smaller finds, like pottery. Still, Dörpfeld is remembered for bringing more order and carefulness to archaeology. He also helped save many archaeological sites from Schliemann's less careful digging methods.

In 1924, a plant found in Cuba was named Doerpfeldia cubensis to honor Dörpfeld.

See also

In Spanish: Wilhelm Dörpfeld para niños

In Spanish: Wilhelm Dörpfeld para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |