William James Sidis facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William James Sidis

|

|

|---|---|

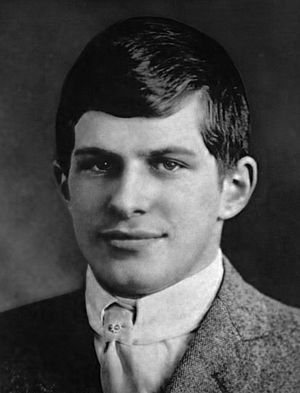

Sidis at his Harvard graduation (1914)

|

|

| Born | April 1, 1898 Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

|

| Died | July 17, 1944 (aged 46) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Other names |

|

| Alma mater | Harvard University Rice Institute Harvard Law School |

|

Notable work

|

|

William James Sidis (born April 1, 1898 – died July 17, 1944) was an American child prodigy. He was incredibly smart, especially in math and languages. He wrote a book called The Animate and the Inanimate in 1925. In this book, he shared his ideas about how life might have started.

William's father, Boris Sidis, was a psychiatrist who wanted his son to be very gifted. William became famous for being so smart at a young age. Later, he became known for being a bit unusual and for wanting to stay out of the public eye. He stopped focusing on math and wrote about other topics using different names. He went to Harvard when he was only 11 years old. As an adult, people said he had a very high IQ. They also said he could speak about 25 different languages and dialects. Many people who knew him, like Norbert Wiener and William James, agreed he was extremely intelligent.

Contents

William James Sidis: A Child Genius

Early Life and Amazing Talents

William James Sidis was born in New York City on April 1, 1898. His parents were Jewish immigrants from Ukraine. His father, Boris, came to the U.S. in 1887 to escape unfair treatment. His mother, Sarah, and her family also fled from violence in the late 1880s. Sarah went to Boston University and became a doctor. William was named after his godfather, William James, who was a famous philosopher. Boris was a psychiatrist who wrote many books. He could speak many languages, and William also learned many languages when he was very young.

William's parents believed in helping him love learning from a very early age. Some people criticized their parenting style. But William could read The New York Times when he was just 18 months old! By the time he was eight, he had reportedly taught himself eight languages. These included Latin, Greek, French, Russian, German, Hebrew, Turkish, and Armenian. He even invented his own language, which he called "Vendergood."

Harvard University and College Years

In 1909, William Sidis made history by becoming the youngest person ever to enroll at Harvard University. He was only 11 years old. Harvard had previously said he was too young to join at age 9.

In 1910, William showed how well he understood advanced math. He gave a lecture to the Harvard Mathematical Club about "four-dimensional bodies." This talk got attention from all over the country. Norbert Wiener, another child prodigy who was also at Harvard, said William's talk was amazing. He wrote that it "would have done credit to a first or second-year graduate student of any age." Daniel F. Comstock, a physics professor at MIT, praised William greatly. He compared him to the famous mathematician Karl Friedrich Gauss. Comstock predicted that William would become a great mathematician. William started taking full college classes in 1910. He earned his Bachelor of Arts degree on June 18, 1914, when he was 16.

After graduating, William told reporters he wanted to live a "perfect life." He said the only way to do this was to live away from others. He later enrolled in Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

Teaching and Further Studies

After some Harvard students bothered William, his parents helped him get a job. He became a math teaching assistant at the William Marsh Rice Institute (now Rice University) in Houston, Texas. He arrived at Rice in December 1915, at age 17. He was also working towards his doctorate degree.

William taught three classes: Euclidean geometry, non-Euclidean geometry, and freshman math. He even wrote a textbook for the Euclidean geometry course in Greek! After less than a year, William left his job. He was not happy with the department, his teaching duties, or how older students treated him. When a friend asked why he left, he said, "I never knew why they gave me the job in the first place—I'm not much of a teacher." William stopped trying to get a higher degree in math. In September 1916, he enrolled in Harvard Law School. He left in March 1919, during his final year.

Public Life and Challenges

In 1919, after leaving law school, William was arrested. He had taken part in a public parade in Boston that became violent. He was sentenced to 18 months in prison. This arrest was big news because he was famous for graduating from Harvard so young. During his trial, William said he was a conscientious objector during World War I. This meant he refused to fight because of his beliefs. He also said he was a socialist. His father helped him stay out of prison. Instead, his parents kept him at their special center in New Hampshire for a year. Then they took him to California for another year.

After returning to the East Coast in 1921, William wanted to live a quiet, independent life. He took simple jobs, like running adding machines. He worked in New York City and grew apart from his parents. It took years before he could legally return to Massachusetts. He worried for a long time about being arrested again. He collected streetcar tickets and wrote his own small magazines. He also taught his friends his ideas about American history. In 1935, he wrote a book called The Tribes and the States. This book talked about how Native Americans helped shape American democracy.

In 1944, William won a legal case against The New Yorker magazine. The magazine had published an article about him in 1937. He said the article had many false statements. The article described his life as lonely. Earlier, he had lost a similar case about the same article. The judge felt bad for William, but said that public figures could not always stop the press from writing about their private lives.

Later Life and Passing

William Sidis passed away in 1944 in Boston. He was 46 years old. He died from a cerebral hemorrhage, which is a type of bleeding in the brain.

William's Writings and Interests

William Sidis wrote about many different subjects. These included ideas about the universe, Native American history, and even streetcar systems. He also had ideas about how time might work differently in space.

The Animate and the Inanimate

In his book The Animate and the Inanimate (1925), William shared his thoughts on how life began and how the universe works. He suggested that there are parts of space where the laws of physics might work in reverse. He believed that life has always existed and has changed through evolution. He also thought that stars might be "alive" in a way, going through cycles of light and dark. This book was mostly ignored when it came out. It was found again in an attic in 1979.

Vendergood Language

When he was only 8 years old, William created his own constructed language called Vendergood. He wrote about it in his second book, the Book of Vendergood. This language was mostly based on Latin and Greek. It also used parts of German and French. Vendergood had eight different ways to express ideas, like telling someone to do something or wishing for something. It also used a base 12 number system instead of our usual base 10.

Here are some examples from his book:

- 'Do I love the young man?' = Amevo (-)ne the neania?

- 'The bowman obscures.' = The toxoteis obscurit.

- 'I am learning Vendergood.' = (Euni) disceuo Vendergood.

- 'What do you learn?' (sing.). = Quen diseois-nar?

- 'I obscure ten farmers.' = Obscureuo ecem agrieolai.

The Tribes and the States

The Tribes and the States is a book William wrote around 1935. It tells the history of Native Americans, especially those from the Northeastern parts of the U.S.. He wrote this book using the name "John W. Shattuck." Much of the information came from wampum belts. William explained that wampum belts were a way of writing using colored beads. Different bead designs meant different ideas.

The book mainly talks about how Native Americans influenced the Europeans who came to America. It also discusses how Native Americans helped shape the early United States. He believed that the idea of different groups joining together, like the Native American federations, was important to the Founding Fathers of the U.S.

Other Interests

William was also very interested in transportation, especially streetcar systems. He even made up a word for people fascinated with transportation research: "peridromophile." He wrote about streetcar tickets, suggesting ways to make public transport better. In 1930, he received a patent for a special perpetual calendar that could figure out leap years.

William's Legacy

After William's death, his sister Helena said his IQ was "the very highest that had ever been obtained." However, later writers found that some of his biographers, like Amy Wallace, might have made his IQ seem higher than it was.

It's known that William's mother, Sarah, sometimes made exaggerated statements about her family. Helena also wrongly said that a Civil Service exam William took in 1933 was an IQ test. She claimed his score of 254 was his IQ, but it was likely his rank on the list of people who passed the exam. Helena also said William knew all the languages in the world. His mother even claimed he could learn a language in just one day! William's father, Boris, did not believe in IQ tests, calling them "silly."

Even with some exaggerations, people who knew William, like MIT Physics professor Daniel Frost Comstock and mathematician Norbert Wiener, agreed he was truly brilliant.

William Sidis's life and work, especially his ideas about Native Americans, are discussed in Robert M. Pirsig's book Lila: An Inquiry into Morals (1991). Norbert Wiener also wrote about William in his own autobiography, Ex-Prodigy.

Discussions on Education

William's unique upbringing led to many discussions about the best way to educate children. Newspapers often criticized his father's methods. Many educators at the time believed that schools should give all children similar experiences to help them become good citizens. Most psychologists thought intelligence was something you were born with, not something you could teach early at home.

The challenges William faced in college might have made people think it was not good for very smart children to go to college too early. However, research now shows that challenging schoolwork can help gifted children with social and emotional difficulties. Because of this, some colleges now allow younger students to enroll early.

The newspapers often made fun of William. The New York Times, for example, called him "a wonderfully successful result of a scientific forcing experiment." His mother later said that what the newspapers wrote about her son was not true to who he was.

See also

In Spanish: William James Sidis para niños

In Spanish: William James Sidis para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |