William O'Connell Bradley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William O'Connell Bradley

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 32nd Governor of Kentucky | |

| In office December 10, 1895 – December 12, 1899 |

|

| Lieutenant | William J. Worthington |

| Preceded by | John Y. Brown |

| Succeeded by | William S. Taylor |

| United States Senator from Kentucky |

|

| In office March 4, 1909 – May 23, 1914 |

|

| Preceded by | James B. McCreary |

| Succeeded by | Johnson N. Camden Jr. |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 18, 1847 Garrard County, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | May 23, 1914 (aged 67) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Frankfort Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Margaret Robinson Duncan |

| Relations | Thomas Z. Morrow (brother-in-law) Edwin P. Morrow (nephew) |

| Profession |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Union Army |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

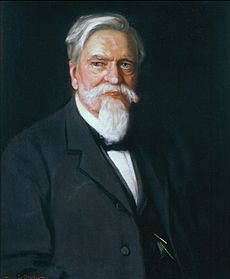

William O'Connell Bradley (March 18, 1847 – May 23, 1914) was a well-known politician from Kentucky. He served as the 32nd Governor of Kentucky. Later, he was chosen by the state legislature to be a U.S. senator for Kentucky. Bradley was the first Republican to become governor of Kentucky. Because of this, he was often called the "father of the Republican Party in Kentucky."

Early in his career, Bradley faced challenges because Kentucky was mostly a Democratic state. He lost elections for the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate multiple times. He became famous nationally after a speech at the 1880 Republican National Convention. He was nominated for governor in 1887 but lost. However, he greatly reduced the usual Democratic lead. In 1895, he was nominated for governor again. He won by taking advantage of disagreements within the Democratic Party. His time as governor was marked by political fights and some violence. He worked to improve the lives of African Americans in the state. However, a Democratic majority in the state legislature made it hard for him to pass many of his civil rights ideas.

After Bradley's term, Republican William S. Taylor was elected governor in a very close election in 1899. When the Democratic candidate, William Goebel, challenged the results, Bradley joined the legal team for the Republicans. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court. The court eventually sided with the Democrats. Even though he was from the minority party, Bradley was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1907. This happened because of more divisions within the Democratic Party. Bradley was against Prohibition, which made him more appealing to some Democrats than their own candidate, Governor Beckham. After many votes, four Democratic lawmakers switched their votes and elected Bradley. His time in the Senate was not very eventful. On the day he announced he would not run for re-election, he was in a streetcar accident. He died from his injuries on May 23, 1914.

Contents

Early Life and Education

William O'Connell Bradley was born on March 18, 1847. His birthplace was near Lancaster, Kentucky in Garrard County, Kentucky. He was the youngest child of Robert McAfee and Nancy Ellen Bradley. His family later moved to Somerset, Kentucky. There, William was taught by private teachers and attended a private school.

When the American Civil War began, he tried twice to join the Union Army. Both times, his father removed him because he was too young. Even with only a few months of service, many people called him "Colonel Bradley" for the rest of his life.

In 1861, Bradley worked as a page in the Kentucky House of Representatives. He studied law with his father, who was a leading lawyer in Kentucky. Kentucky law usually required people to be 21 to take the bar examination. However, a special law allowed Bradley to take it at age 18. He passed the exam and became a lawyer in 1865. He then joined his father's law firm. He later received an honorary law degree from Kentucky University (now Transylvania University).

On July 13, 1867, Bradley married Margaret Robertson Duncan. He changed his faith to Presbyterianism, his wife's religion. They had two children: George Robertson Bradley and Christine (Bradley) South.

Starting His Political Journey

Bradley's political career began in 1870. He was elected as the prosecuting attorney for Garrard County. As a Republican in a mostly Democratic area, he didn't win many early elections. He lost twice for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. In 1875, his party nominated him for the U.S. Senate. He was too young to legally hold the office, but all Republicans in the state legislature voted for him.

Bradley was chosen as a delegate to six Republican National Conventions in a row. At the 1880 convention in Chicago, he gave a powerful speech. This speech brought him attention from important party leaders. He was also asked by President Chester A. Arthur to help with a financial case in 1885. However, Bradley resigned due to disagreements.

Running for Governor in 1887

In 1887, Kentucky Republicans nominated Bradley for Governor. He ran against Democrat Simon Bolivar Buckner, a former Confederate general. Bradley urged Kentuckians to move past the Civil War. He wanted them to stop only electing former Confederate Democrats. His plan included improving education and developing Kentucky's resources. He pointed out that Kentucky had a lot of coal but bought much of it from other states.

During the campaign, Buckner was popular and had strong party support. Bradley was a better speaker. In their only debate, Bradley criticized Democrats for wasteful spending. He also supported a protective tariff and federal help for education. Buckner then accused Bradley of spreading false rumors about his speeches. After this, Buckner refused to debate Bradley again.

Rumors spread that Buckner was afraid to debate Bradley. Bradley did little to stop these rumors. Some Democrats also criticized their own party's record. Bradley kept talking about the need to check the state's money. He lost the election by over 16,000 votes. However, he had the best showing for a Republican governor candidate up to that time. He also got strong support from black voters. Bradley's concerns about the state's money were proven right. In 1888, the state treasurer, James Tate, ran away with $250,000 from the state treasury and was never found.

In 1888, Bradley was again considered for the U.S. Senate but lost. He also received votes for the Vice-Presidential nomination. President Benjamin Harrison offered him a position as Minister to Korea in 1889. Bradley turned it down, choosing to stay in Kentucky for future political chances. He was elected to the Republican National Committee three times.

Running for Governor in 1895

Bradley announced his plan to run for governor early in 1895. He was nominated easily by the Republicans. The main issue in this election was whether the country should use a gold standard for money or allow the coinage of silver (called "free silver"). Republicans strongly supported the gold standard.

Democrats were divided on the money issue. Their candidate, Parker Watkins Hardin, supported free silver. But the Democratic party's platform was unclear. Most people thought it favored gold. This left many Democrats unsure where their candidate stood.

The campaign started in Louisville. Hardin openly supported free silver, which divided his party. Bradley repeated many of his arguments from 1887. He blamed Democrats for mismanaging the state government. He pointed to the missing state treasury money as proof. He also connected Hardin to the missing money, as Hardin was the state's attorney general at the time. Bradley also blamed the national economic problems on the Democratic President.

In one debate, Hardin tried to counter Bradley by saying that electing a Republican would lead to "Negro domination" in the state. This put Bradley in a tough spot. If he ignored the issue, he might lose black votes. If he acknowledged it, he might lose white votes. Bradley tried to avoid the race question. He focused instead on Hardin's connection to the missing money. After a difficult debate where he was heckled, Bradley stopped participating in joint debates. Many believed he was looking for a reason to avoid the race issue.

In the election, Bradley won the votes of many Democrats who supported the gold standard. He also gained support from anti-immigrant groups. Democrats were also hurt by economic problems and a severe drought. Bradley became the first Republican governor of Kentucky. He defeated Hardin by 172,436 votes to 163,524. The Populist candidate received 16,911 votes, mostly from Democrats.

Governor of Kentucky

Bradley became governor on December 10, 1895. During his time, Republicans controlled the Kentucky House of Representatives. However, Democrats controlled the Kentucky Senate. This led to many disagreements between the two parts of the state government and with the governor.

Legislative Challenges

In Bradley's first legislative session, many bills were proposed. These included a ban on cigarettes, making carrying a hidden weapon a serious crime, and banning gambling. Bradley also wanted a law against lynching. However, most of the session focused on electing a U.S. Senator.

Democrats were divided on who to support for Senator. Republicans nominated W. Godfrey Hunter. No candidate could get enough votes. The voting went on for many days. People in the viewing areas became very loud. Tensions grew, and armed Democratic supporters stood outside the state house to try and scare Republican lawmakers.

Bradley called the state militia to Frankfort to keep order. He even thought about moving the session to Louisville for better security. Some Democrats praised Bradley for keeping order. But Democratic lawmakers in the Senate tried to accuse Bradley of interfering with the election. They wanted to fine him and put him in jail. On March 16, Governor Bradley declared martial law in the capital. The session ended that day without electing a senator. One newspaper said it was "hard to conceive how a legislature would go about accomplishing less."

Bradley called a special session in March 1897 to continue voting for senator. After much debate and many votes, William Joseph Deboe was finally elected. He became the first Republican senator from Kentucky.

Helping African American People

Bradley did a lot to help African American people in Kentucky. He spoke out against racially motivated lynchings. He demanded that county officials take action against racial violence. He called a special legislative session in March 1897 to consider an anti-lynching bill. This bill would punish law enforcement officers who failed to prevent lynchings. It also allowed officers to get help from other people to protect prisoners. The bill quickly passed and Bradley signed it on May 11, 1897. During Bradley's four years as governor, the number of lynchings in the state went down.

Other Issues During His Term

When the legislature met in 1898, Democrats had a very large majority. Bradley asked for many changes. He wanted to cut spending, put state charities under a non-political board, and improve education.

The legislature mostly ignored the governor's requests. They passed a pure food and drug law without his signature. Bradley's veto of a law about railroad rates was upheld. Both parts of the legislature asked Senator William Lindsay to resign. They said he no longer represented his party's interests. Lindsay refused, saying he represented the people of Kentucky.

Bradley also spoke about the poor condition of the Governor's Mansion. He said it was falling apart and uncomfortable. Instead of fixing it, the legislature passed a law taking control of the mansion away from the governor. On February 10, 1899, the mansion caught fire. It was very cold, and firefighters had trouble with frozen water. The mansion was badly damaged. Even though it was insured, the legislature only made minimal repairs for the Republican governor. The Bradleys stayed with a neighbor and then at a hotel before moving back into the repaired mansion.

Bradley also tried to end violent feuds in eastern Kentucky. During his term, there were "Tollgate Wars." Private companies built roads and charged tolls. Poor residents felt the tolls were too high. They wanted "free roads" and resorted to violence, burning toll houses. Bradley wanted strong action against this violence. But the Democratic legislature, who felt sympathy for the poor, refused to act.

Kentucky's soldiers in the Spanish–American War faced poor conditions and disease in army camps. Many men died from these conditions. When it was time for the troops to come home, Bradley found the state had no money for hospital trains. Bradley personally borrowed money from a bank to bring the soldiers home.

The Goebel Election Law and 1899 Election

In 1898, a law called the Goebel Election Law was passed. This law created a Board of Election Commissioners chosen by the General Assembly. This board would decide election results. Because the General Assembly was mostly Democratic, and William Goebel was likely to run for governor, many saw this law as unfair. Bradley vetoed the bill, but the legislature overrode his veto.

Republicans tried to challenge the law in court, but the Kentucky Court of Appeals said it was constitutional. Goebel, as the party leader, chose the members of the Election Commission. He picked three strong Democrats.

As Bradley's term ended, few Republicans wanted to run for governor. They feared the state would vote Democratic and that the Goebel Election Law would make it impossible to win. Attorney General William S. Taylor was the first to announce his candidacy. He gained strong support.

The Republican convention nominated Taylor. Bradley was initially cool toward Taylor. However, he agreed to tour the state with Republican leader Augustus E. Willson. Bradley defended his time as governor and encouraged African American people to support the Republican Party. He also highlighted his appointments of African Americans to his cabinet.

As the election neared, both parties warned of possible fraud and violence. On election day, November 7, it was mostly calm. The results were very close. Taylor won by a small margin. The Board of Elections, which many thought Goebel controlled, surprisingly certified Taylor's win. Taylor was sworn in as governor on December 12, 1899.

After leaving office, Bradley moved to Louisville and continued his law practice. Soon after, Goebel challenged the election results. Bradley joined the legal team for the Republicans. On January 30, Goebel was shot and wounded. He was sworn in as governor but died on February 3. His running mate, J. C. W. Beckham, then became governor.

Bradley argued in federal court that the Goebel Election Law took away citizens' right to vote. He said this right was protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. The court refused to get involved, saying it was a state issue. The cases eventually went to the Supreme Court of the United States. Bradley argued that the election committee was biased. The Supreme Court also refused to intervene.

Later Life and Passing

In 1900, Bradley lost an election for a U.S. Senate seat. The state Republican party then split into two groups. In 1904, Bradley supported Augustus E. Willson for governor. However, another candidate was nominated and lost the election.

Serving in the Senate

In 1907, Republicans nominated Willson for governor, and he won. This victory gave Republicans more confidence. In 1908, they nominated Bradley for a U.S. Senate seat. Democrats nominated outgoing Governor Beckham. Even though Democrats had a majority, seven Democratic lawmakers refused to vote for Beckham because he supported Prohibition. After two months of voting, four Democrats who favored Bradley's stance switched their votes. Bradley was elected by a vote of 64–60. He became a U.S. Senator.

During his time in the Senate, Bradley was known more for his speeches than for new laws. He disappointed African Americans by supporting a policy that limited their appointments to government jobs in their home states.

In the 1908 presidential election, Bradley supported Charles W. Fairbanks. However, his state party supported William Howard Taft. This caused disagreements within the party. Bradley was not chosen as a delegate to the Republican National Convention. This ended his alliance with Governor Willson. In 1911, Bradley did not strongly support his party's candidate for governor, who then lost the election.

On May 14, 1914, Bradley announced he would retire from politics due to his declining health. As he was rushing to board a streetcar after his announcement, he fell badly. He broke two fingers and suffered head and internal injuries. He died on May 23, 1914. His cause of death was listed as kidney failure. Both houses of Congress expressed their sympathy and adjourned out of respect. His body was returned to Frankfort and buried in the state cemetery.

Images for kids

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |