Women's education in the United States facts for kids

In the early days of the United States, when it was still a group of colonies, higher education was mostly for men. Over time, starting in the 1800s, women gained more chances to go to school and college. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, more women than men started earning bachelor's and master's degrees each year. This trend continued, with women making up the majority of graduates for these degrees. Since 2005, the same thing has happened with doctorate degrees, where more women now earn them than men.

How Many Women Go to College?

Since the early 1970s, more women have been enrolling in college and graduating than men.

Here's a look at how many women earned degrees between 1950 and 1980:

| Year | % of bachelor's degrees | % of Doctorate degrees |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 23.9% | 9.7% |

| 1960 | 35% | 10.5% |

| 1970 | 41.5% | 13.3% |

| 1980 | 49% | 30.3% |

In the 1930s, about 480,000 to 481,000 women were enrolled in higher education in the U.S. Different groups counted this number in slightly different ways.

More Women Graduating Than Men

In the late 1970s, for the first time, more women than men were earning undergraduate degrees. Since 1981, women have consistently earned more bachelor's degrees than men. For example, in 1980, women had a 1% lead, but by 2015, they had a 33% advantage. This means that for every 100 men who graduate, about 134 women do. Also, there are many more scholarships available specifically for women than for men.

Here's a table showing the percentage of college degrees earned by women over the years:

| Year | Associate's | Bachelor's | Master's | Doctorate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970-1971 | 42.9% | 43.4% | 39.3% | 10.6% |

| 1980-1981 | 54.7% | 49.8% | 49.5% | 29.0% |

| 1990-1991 | 58.8% | 53.9% | 53.1% | 39.1% |

| 2000-2001 | 61.6% | 57.3% | 58.2% | 46.3% |

| 2010-2011 | 61.7% | 57.2% | 60.1% | 51.4% |

| 2020-2021 | 61.1% | 57.7% | 60.7% | 54.1% |

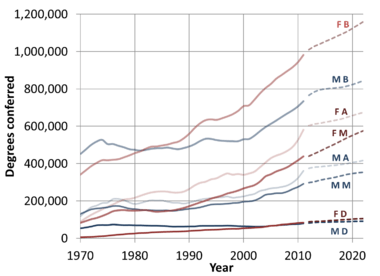

This graph shows how the percentage of degrees earned by women has changed over time:

History of Women's Education

Colonial Times

In Colonial America, basic education was common in New England. People there, especially the Puritans, believed everyone needed to read the Bible. So, boys and girls learned to read early. Towns even had to pay for primary schools.

Most girls didn't go to formal schools. They learned at home or at "Dame schools," where women taught reading and writing in their own homes. By 1750, almost all men and nearly 90% of women in New England could read and write. However, there was no higher education for women back then.

Public schools that were paid for by taxes started teaching girls in New England as early as 1767. Some towns were slow to do this. For example, Northampton, Massachusetts, didn't want to use taxes to educate girls from poorer families. They used taxes to prepare boys for college instead. It wasn't until after 1800 that Northampton used public money to educate girls. In contrast, Sutton, Massachusetts, started paying for schools for both boys and girls much earlier.

Historians note that reading and writing were seen as different skills. Schools taught both. But in places without schools, mostly boys learned to read and write. Girls often only learned to read, especially religious texts. This is why many colonial women could read but couldn't write their names; they used an "X" instead.

In the Southern colonies, there were very few public schools. Most children learned at home with tutors or went to small private schools.

Early Ideas About Girls' Education

During the 1600s, many people in the colonies didn't think it was important for women to get an education. Some even thought it was unnecessary or dangerous. Women were mostly expected to be mothers and take care of the home. Their value came from doing domestic tasks well, not from being smart or educated.

Men had more power and control in society. Because of this, women were often seen as less capable, and their minds were not thought to need much development.

However, girls did learn basic reading and writing. Mothers often taught young children at home. Some women, like Anne Bradstreet and Phillis Wheatley, even wrote and published poetry. Diaries from the time show that both boys and girls read the Bible at night and were praised for it. But getting higher education was still very difficult for women.

Slowly, these ideas changed. More people started to believe that women should have better access to education. For example, in 1687, some people in Farmington, Connecticut, pushed for their town school to include girls, a fight that continued for centuries.

The 1800s: Big Changes

In the early 1800s, only a small number of American children, both boys and girls, spent much time in school. Even fewer got a high school education. For girls, the focus was on learning "ladylike" manners and skills. In 1821, Emma Willard started her Female Seminary. She believed young women should learn to fit into their "place in society" and thought the idea of women graduating from college was "absurd." Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who went to Willard's Seminary, disliked this idea. This experience later helped her become a leader in the women's rights movement. A few private colleges, like Oberlin in 1833, started accepting women, but state colleges mostly only allowed men.

The second half of the 1800s brought much faster progress for women's education. Many new colleges for women were founded, such as Vassar (1865), Wellesley (1875), Smith (1875), Bryn Mawr (1885), Radcliffe (1879), and Barnard (1889). These colleges were filled with female high school graduates, who were already the majority of high school graduates. High school enrollment tripled in the 1890s, with girls still making up most of the students.

Between 1867 and 1915, 304 new colleges and universities opened, bringing the total to 563. In many state colleges, like the University of Colorado and the University of Iowa, there were more women than men on the teaching staff. The president of the University of Wisconsin even suggested limiting the number of women students.

The 1900s: Fighting for Equality

At the start of the 20th century, during the first wave of feminism, women fought for equal rights in education. After long struggles, women finally gained the right to be educated through new government laws, colleges opening their doors, and chances to go to higher education.

Before education reforms, boys and girls often studied different subjects. Girls were often taught skills for jobs society thought were suitable for them, like secretaries or social workers. This "differentiated curriculum" meant that high schools helped shape gender roles. There was a push to make women "domesticated citizens" rather than scholars. Even though women's voices were starting to be heard, some people still doubted their ideas. Girls of different races and backgrounds also started entering public schools, and their studies were sometimes affected by their race.

The 1930s

Education was a big topic in the 1930s. Some schools separated boys and girls to "protect the virtue of female high school students." Home economics and industrial education became new parts of the high school curriculum, clearly designed for women's jobs. These classes taught women practical skills like sewing, cooking, and using new household inventions. However, this training often didn't help women get stable jobs with good pay.

The 1930s also saw huge changes for women in college. In 1900, about 85,000 women were in college, and 5,237 earned bachelor's degrees. By 1940, there were over 600,000 female college students, and 77,000 earned bachelor's degrees. This increase happened partly because people started to see that higher education could help women in their roles as wives, mothers, citizens, and professionals.

In the 1930s, it was generally expected that white, middle-class women would marry. Some thought college-educated women were less likely to marry. Others argued that college made women better wives and mothers by teaching them practical skills.

The 1930s were also a time of great economic hardship due to the Great Depression. People needed to justify the cost of college. Many women had to get grants, scholarships, or fellowships to pay for their degrees. Even with help, most saved money for years because the aid wasn't enough. Despite these challenges, the 1930s were a peak time for women earning PhDs. These degrees were in many different fields, opening up areas for women that were once closed.

To help families pay for education, the U.S. Government created the National Youth Administration (NYA). Between 1935 and 1943, the NYA provided nearly $93 million in financial aid. Even with more opportunities, women still had to prove the value of their education. As more people graduated, those who lost jobs during the Depression had to compete with younger, more educated people.

The 1930s also marked 10 years since women gained the right to vote. Even with voting rights, women were often kept out of political power. This struggle led to new forms of political activism and more support for an Equal Rights Amendment.

Popular Subjects for Women

In the 1930s, teaching and nursing were the most popular fields for women. Home economics also became very popular during the Depression. This field brought a scientific approach to traditional housework, making "homemaking" a respected, though still female, job. Social work, child development, and nursery school programs were also common.

Women also slowly started to enter fields traditionally dominated by men, like business, science, medicine, architecture, engineering, and law. They also gained important positions in the federal government during the New Deal era.

Women's Colleges

Before the American Civil War, few colleges accepted women. Salem College, founded in 1772 as a primary school, is the oldest educational place for females. However, it didn't give out college degrees until 1890.

Some colleges started by accepting both men and women. Oberlin College, founded in 1833, was the first college to accept both women and African Americans. Other early co-educational schools included Hillsdale College (1844) and Antioch College (1852). Hollins University started as co-educational in 1842 but became all-female in 1852.

Many colleges for women only were founded before the Civil War. These include Mount Holyoke College (1837), Wesleyan College (1836), which was the first college chartered to grant degrees to women, and Vassar College (1861).

During the Civil War, many men went to fight, creating more opportunities for women in schools. Slowly, more colleges opened their doors to women. Today, there are 60 women's colleges in the United States, offering education similar to co-educational universities.

Government Actions for Equality

In 1848, the Seneca Falls Convention was held in New York to support education and voting rights for women. While it didn't have an immediate effect, it laid the groundwork for future efforts toward equal education for women.

The Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act of 1862 created universities to educate both men and women in practical subjects. However, women's courses still focused on home economics. By 1870, 30% of colleges were co-educational. Later, in the 1930s, women-only colleges were established, offering more academic and intellectual courses beyond domestic skills.

In July 1975, Title IX became law. This law made it illegal to discriminate against anyone based on their sex in any educational program that received federal money. Schools had a few years to follow this law. Over the years, there were court cases that sometimes limited Title IX's reach, but the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987 helped bring back its full power. In the 1990s, more changes were made, allowing people to sue for money if they faced discrimination and requiring schools to report their operations publicly. In the 2000s, new rules allowed email surveys and parents could bring lawsuits for discrimination.

Timeline of Key Events

1727: Ursuline Academy, New Orleans, founded by the Sisters of the Order of Saint Ursula, became the oldest continuously operating school for girls and the oldest Catholic school in the U.S.

1742: Moravians in Pennsylvania started the first all-girls boarding school in America, the Bethlehem Female Seminary. It later became a college.

1772: Salem Academy and College began as a school for young girls in North Carolina. It is the oldest educational institution for both girls and women in the U.S.

1783: Washington College in Chestertown, Maryland, hired the first women instructors at any American college: Elizabeth Callister Peale and Sarah Callister taught painting and drawing.

1803: Bradford Academy in Massachusetts was the first higher education institution in the state to admit women.

1826: The first American public high schools for girls opened in New York and Boston.

1829: The first public test of an American girl in geometry took place.

1831: Mississippi College became the first coeducational college in the U.S. to grant degrees to women, Alice Robinson and Catherine Hall.

1835: Ingham University in New York was the first women's college in New York State and the first chartered women's university in the U.S.

1836: Georgia Female College (now Wesleyan College) in Macon, Georgia, was the first school established as a full college for women, offering the same education as men. It awarded the first known bachelor's degree to a woman.

1837: Bradford Academy became an all-girls institution.

1837: Mount Holyoke College, first called Mount Holyoke Seminary, was founded by Mary Lyon in Massachusetts.

1844: Margaret Fuller was the first woman allowed to use the Harvard College library.

1849: Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to earn a medical degree from an American college.

1850: Lucy Sessions became the first African American woman in the U.S. to receive a college degree, from Oberlin College.

1851: The Adelphean Society, now Alpha Delta Pi, was founded at Wesleyan Female College, becoming the first secret society for women.

1855: The University of Iowa became the first coeducational public or state university in the U.S.

1858: Mary Fellows was the first woman west of the Mississippi River to receive a bachelor's degree.

1862: Mary Jane Patterson became the first African-American woman to earn a BA, from Oberlin College.

1863: Mary Corinna Putnam Jacobi was the first woman to graduate from a U.S. school of pharmacy.

1864: Rebecca Crumpler became the first African-American woman to graduate from a U.S. college with a medical degree.

1866: Lucy Hobbs Taylor became the first American woman to earn a dental degree.

1866: Sarah Jane Woodson Early became the first African-American woman to serve as a professor.

1869: Fanny Jackson Coppin became the first African-American woman to lead a higher learning institution in the U.S.

1870: Ada Kepley became the first American woman to earn a law degree.

1870: Ellen Swallow Richards became the first American woman to earn a degree in chemistry.

1871: Frances Elizabeth Willard became the first female college president in the U.S.

1871: Harriette Cooke became the first woman college professor in the U.S. to be appointed full professor with equal pay to men.

1871: Japanese women were allowed to study in the USA.

1873: Linda Richards became the first American woman to earn a degree in nursing.

1877: Helen Magill White became the first American woman to earn a Ph.D.

1878: Mary L. Page became the first American woman to earn a degree in architecture.

1879: Mary Eliza Mahoney became the first African-American in the U.S. to earn a diploma in nursing.

1881: American Association of University Women was founded.

1883: Susan Hayhurst became the first woman to receive a pharmacy degree in the U.S.

1886: Winifred Edgerton Merrill became the first American woman to earn a PhD in mathematics.

1889: Maria Louise Baldwin became the first African-American female principal in Massachusetts, supervising white staff and students.

1889: Susan La Flesche Picotte became the first Native American woman to earn a medical degree.

1890: Ida Gray became the first African-American woman to earn a Doctor of Dental Surgery degree.

1892: Laura Eisenhuth became the first woman elected to state office as Superintendent of Public Instruction.

1894: Margaret Floy Washburn became the first woman to be officially awarded a PhD in psychology.

Late 1800s: Anandibai Joshi (India), Keiko Okami (Japan), and Sabat Islambouli (Syria) became the first women from their countries to get a degree in Western medicine.

1900: Otelia Cromwell became the first African-American woman to graduate from Smith College.

1903: Mignon Nicholson became the first woman in North America to earn a veterinary degree.

1904: Helen Keller graduated from Radcliffe, becoming the first deafblind person to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree.

1905: Nora Stanton Blatch Barney became the first woman to earn an engineering degree in the U.S. (civil engineering).

1908: Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority, the first African-American Greek letter organization for women, was founded.

1909: Ella Flagg Young became the first female superintendent of a large city school system.

1915: Lillian Gilbreth earned the first PhD ever granted in industrial psychology.

1917: Sigma Delta Tau sorority, a Jewish women's Greek letter organization, was founded.

1918: The College of William & Mary admitted women to its undergraduate class.

1921: Sadie Tanner Mossell became the first African-American woman to earn a Ph.D. in the U.S. (Economics).

1922: Sigma Gamma Rho sorority was founded, the first African-American sorority on a predominantly white campus.

1922: Lorna Myrtle Hodgkinson became the first woman to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard.

1923: Virginia Proctor Powell Florence became the first African-American woman to earn a degree in library science.

1925: Zora Neale Hurston became the first African-American woman admitted to Barnard College.

1926: Dr. May Edward Chinn became the first African-American woman to graduate from the University and Bellevue Hospital Medical College.

1929: Jenny Rosenthal Bramley became the first woman to earn a Ph.D. in physics in the U.S.

1931: Jane Matilda Bolin was the first African-American woman to graduate from Yale Law School.

1932: Dorothy B. Porter became the first African-American woman to earn an advanced degree in library science.

1933: Inez Beverly Prosser became the first African-American woman to earn a PhD in psychology.

1934: Ruth Winifred Howard became the second African-American woman to receive a Ph.D. in psychology.

1935: Jesse Jarue Mark became the first African American woman to earn a Ph.D. in botany.

1936: Flemmie Kittrell became the first African American woman to earn a Ph.D. in nutrition.

1937: Anna Johnson Julian became the first African-American woman to receive a Ph.D. in sociology.

1940: Roger Arliner Young became the first African-American woman to earn a Ph.D. in zoology. Marion Thompson Wright became the first African-American woman to earn a Ph.D. in History.

1941: Ruth Lloyd became the first African-American woman to earn a Ph.D. in anatomy.

1941: Merze Tate became the first African American woman to earn a Ph.D. in government and international relations from Harvard.

1942: Margurite Thomas became the first African American woman to earn a Ph.D. in geology.

1943: Euphemia Haynes became the first African-American woman to earn a Ph.D. in Mathematics.

1945: Harvard Medical School admitted women for the first time.

1947: Marie Maynard Daly became the first African-American woman to earn a Ph.D. in chemistry.

1949: Joanne Simpson was the first woman in the U.S. to receive a Ph.D. in meteorology.

1951: Maryly Van Leer Peck became Vanderbilt University's first chemical engineer graduate and the first woman to receive an M.S. and a Ph.D. in chemical engineering from the University of Florida.

1952: Georgia Tech admitted its first women students.

1962: Martha Bernal became the first Latina to earn a PhD in psychology.

1963: Grace Alele-Williams became the first Nigerian woman to earn any doctorate (Mathematics Education).

1965: Sister Mary Kenneth Keller became the first American woman to earn a PhD in Computer Science.

1972: Title IX was passed, making sex discrimination illegal in federally funded educational programs.

1972: Willie Hobbs Moore became the first African-American woman to earn a Ph.D. in Physics.

1975: Lorene Rogers became the first woman president of a major research university (The University of Texas).

1975: Jeanne Sinkford became the first female dean of a dental school.

1976: U.S. service academies (like the Military and Naval Academies) first admitted women.

1977: Nancy Goorey became the first female president of the American Association of Dental Schools.

1977–1978: For the first time, more associate degrees were given to women than men in the U.S.

1979: Christine Economides became the first American woman to earn a PhD in petroleum engineering.

1979: Jenny Patrick became the first African-American woman in the U.S. to earn a Ph.D. in chemical engineering.

1980: Women and men were enrolled in American colleges in equal numbers for the first time.

1981–1982: For the first time, more bachelor's degrees were given to women than men in the U.S.

1982: Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan ruled that the Mississippi University for Women's male-only admissions policy was illegal.

1982: Judith Hauptman became the first woman to earn a PhD in Talmudic studies.

1983: Christine Darden became the first African-American woman in the U.S. to earn a Ph.D. in mechanical engineering.

1984: The Supreme Court case Grove City College v. Bell limited Title IX's reach, saying it only applied to programs directly receiving federal aid.

1986–1987: For the first time, more master's degrees were given to women than men in the U.S.

1987: Johnnetta Cole became the first African-American president of Spelman College.

1988: The Civil Rights Restoration Act was passed, extending Title IX to cover all programs at any educational institution receiving federal aid.

1994: Judith Rodin became the first permanent female president of an Ivy League University (University of Pennsylvania).

1994: The Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act required colleges to share information about their sports teams and budgets for men and women.

1996: United States v. Virginia ruled that the Virginia Military Institute's male-only admission policy was illegal.

2001: Ruth Simmons became the first African-American woman to lead an Ivy League institution (Brown University).

2004–2005: For the first time, more doctoral degrees were given to women than men in the U.S. As of 2011, more U.S. women (10.6 million) had master's degrees or higher than men (10.5 million).

2006: Title IX rules were changed to allow more flexibility for single-sex classes or activities in elementary and secondary schools.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |