Xueta facts for kids

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 18,000 - 20,0000 (approx.) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Majorca | |

| Languages | |

| Catalan, Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Xueta Christianity, mainstream Catholicism, Crypto-Judaism; some individuals now reverting to mainstream Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

|

The Xuetes (pronounced shoo-EH-tuh) are a special group of people living on the Spanish island of Majorca in the Mediterranean Sea. They are descendants of Majorcan Jews who were forced to change their religion to Christianity a long time ago. Some were called conversos because they converted, while others were Crypto-Jews, meaning they secretly kept their Jewish faith.

For many years, the Xuetes only married within their own group. Many of their descendants practice a unique form of Christian worship called Xueta Christianity. Until the mid-1900s, Xuetes faced a lot of unfair treatment. Later, as people gained more freedom of religion, the pressure on them lessened. Today, about 18,000 people on Majorca have Xueta surnames, but not everyone knows about their interesting and sometimes difficult history.

Contents

What Does "Xueta" Mean?

The word Xueta comes from the local language of the Balearic Islands. Some experts think it comes from juetó, which is a small version of jueu (meaning "Jew").

Other people believe it comes from xulla (pronounced shoo-yah), which means salted bacon or pork. This idea suggests that Xuetes were seen eating pork to prove they were not practicing Judaism. This meaning is similar to other old, often offensive, names used for Jews or converts.

There's also a third idea that combines both: the word xuia might have changed the "j" in juetó to an "x", creating xuetó, and then xueta.

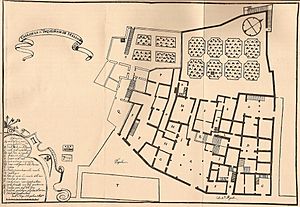

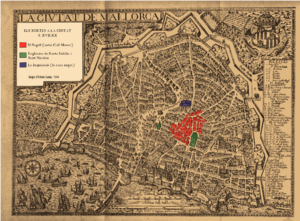

The Xuetes were also called "del Segell" (meaning "of the Seal") or "del carrer" (meaning "of the street"). This was because many of them lived on a specific street, the carrer de l'Argenteria (Silversmiths' Street), where many worked as silversmiths. This street was part of the old Jewish quarter in Palma, Majorca.

Because the word Xueta was often used in an offensive way, the people themselves preferred to call themselves "del Segell", "del carrer", or simply "noltros" or "es nostros" (meaning "us"), as opposed to "ets altres" ("the others").

Xueta Family Names

There are specific family names that are linked to the Xueta community. These are: Aguiló, Bonnin, Cortès, Fortesa, Fuster, Martí, Miró, Picó, Pinya/Piña, Pomar, Segura, Tarongí, Valentí, Valleriola, and Valls.

It's important to know that many of these names are also common among other people in areas where Catalan is spoken. So, just having one of these surnames doesn't automatically mean someone is Xueta.

Some other names like Galiana, Moyà, and Sureda were also linked to converts but are not considered Xueta surnames. There are also many other surnames in Majorca with Jewish origins that are not part of the Xueta community, such as Abraham, Amar, Bonet, and Vidal.

So, while Xuetas are descendants of converts, not all descendants of converts are considered Xuetas.

Xueta Family History in Their Genes

Scientists, especially from the University of the Balearic Islands, have studied the genes of the Xuetes. Their research shows that Xuetes are a unique group with genetic links to other Jewish communities, like those from the Middle East (Mizrahi Jews), Europe (Ashkenazi Jews), and North Africa. This is found by looking at DNA passed down from fathers (Y chromosome) and mothers (mitochondrial DNA).

The Xueta community also has some specific health conditions that are more common among them, like Familial Mediterranean fever, which is also seen in Sephardi Jews.

A Look Back in Time

The Converts (1391-1488)

Majorca's Jewish community faced big changes between 1391 and 1435. First, their neighborhoods (called calls) were attacked in 1391. Then, a preacher named Vincent Ferrer encouraged conversions in 1413. Finally, in 1435, most of the remaining Jewish community converted to Christianity. These conversions were often done to protect the group, not always because of personal religious change.

Many of these "new Christians" secretly continued their Jewish traditions. They formed a group called the "Confraternity of Saint Michael" to help their community, similar to how their old Jewish community (Aljama) used to work. They helped those in need, settled arguments, and supported their religious practices. For a while, they could do this without much trouble.

The Spanish Inquisition Begins (1488-1544)

In 1488, the Spanish Inquisition arrived in Majorca. This was a special court created by the Catholic rulers of Spain to make sure everyone followed the same religion. People in Majorca, and other parts of Spain, didn't like it, but they couldn't stop it.

The Inquisition's main goal was to find and punish "Crypto-Jews" – those who secretly practiced Judaism. They used "Edicts of Grace," which encouraged people to confess their secret Jewish practices to avoid harsher punishments.

Between 1488 and 1492, 559 Majorcans confessed to Jewish practices. The Inquisition learned the names of many others. After this, until 1544, 239 Crypto-Jews were "reconciled" (meaning they confessed and were allowed back into the Church, but often with punishments). Sadly, 537 were "relaxed," meaning they were handed over to civil authorities to be executed. Out of these, 82 were actually burned alive. Many others who fled were "burned in effigy" (meaning a dummy representing them was burned). This was different from the 1492 expulsion of Jews from Spain, as Majorca officially had no Jews left by 1435.

Secret Practices Continue (1545-1673)

After 1544, the Inquisition in Majorca mostly stopped targeting Crypto-Jews, even though some secret practices continued. This might have been because the Inquisition was busy with other issues or because the Crypto-Jews became better at hiding their religion. Trials from later times show that religious practices were often taught within families when children became teenagers, especially to women when they were about to marry.

During this time, many people who had been punished earlier fled the island. Most of those who stayed became truly Catholic. Also, rules about limpieza de sangre (meaning "purity of blood") became common. These rules meant that people with Jewish ancestors were often excluded from guilds (groups of workers) and religious orders.

However, a small group of Xuetes continued their secret practices. They also kept strong family and business ties within their group.

From 1640, the descendants of converts started to become very successful in business. Before, they were mostly artisans and shopkeepers. But now, they started large trading companies and became very involved in foreign trade. They even controlled a large part of the island's trade and insurance market. These businesses were often owned by conversos, and they used some of their profits to help their own community.

Because of their international trade, the Xuetes reconnected with Jewish communities in other cities like Livorno, Rome, and Amsterdam. This allowed them to get Jewish books and learn more about their heritage. For example, Rafel Valls, known as "the Rabbi," a religious leader among the Majorcan converts, traveled to Alexandria and Smyrna.

During this time, a social system likely developed within the Xuete community. Some were called "orella alta" ("high ears"), like an aristocracy, and others were "orella baixa" ("low ears"). These differences, along with jobs and family ties, influenced who married whom within the group.

The Xuetes' Story Continues

The Second Persecution (1673-1695)

It's not entirely clear why the Inquisition started targeting Majorcan Crypto-Jews again after about 130 years. It might have been because of economic competition, a new rise in religious practices, or a specific court case.

Early Signs

In 1672, a merchant told the Inquisition that Jews from Livorno were asking about Majorcan Jews with certain surnames like Forteses and Martins.

In 1673, a ship carrying Jews expelled from Oran stopped in Palma. The Inquisition arrested a 17-year-old named Isaac López. He had been born in Madrid and baptized as Alonso, but had fled with his converso parents. Alonso refused to give up Judaism and was burned alive in 1675. This event deeply affected the "judaizers" and made him a symbol of courage.

That same year, some servants of conversos told their confessors that they had seen their masters practicing Jewish ceremonies.

In 1674, the Majorca Inquisition listed 33 accusations against the Crypto-Jews. These included refusing to marry "natural Christians," keeping secrets, using Old Testament names, identifying with their Jewish tribes, and avoiding New Testament images in their homes. They were also accused of insulting Christians, cheating them in business, and even holding church positions to mock them. They were said to have their own legal system, collect money for their poor, fund a synagogue in Rome, hold secret meetings, follow Jewish dietary laws and fast days, observe the Shabbat (Jewish Sabbath), and avoid Last Rites when dying.

The Conspiracy

In 1677, the Supreme Inquisition ordered the Majorcan Inquisition to act on the servants' confessions. The servants claimed that the "observants" (as they called themselves, referring to the Torah) met in a garden in Palma to observe Yom Kippur. This led to the arrest of leaders like Pere Onofre Cortès and five others. Within a year, 237 people were arrested.

With help from corrupt officials, the accused managed to give limited information and denounce as few people as possible. All of them asked to return to the Church and were "reconciled."

Part of their punishment was that all their belongings were taken away. This amounted to a huge sum of money, so much that it was said there wasn't that much cash on the entire island.

In the spring of 1679, five autos-da-fé (public ceremonies where sentences were announced) took place. The first one was preceded by the destruction of the garden building and the salting of the earth where the conversos met. Before a huge crowd, 221 conversos were condemned. They were sent to new Inquisition prisons, and their goods were taken.

The Cremadissa (Mass Burning)

After serving their prison sentences, many who still held their Jewish faith decided to leave the island. They were watched by the Inquisition and felt harassed by a society they blamed for the economic problems caused by the confiscations.

During this time, a small event led to another wave of arrests. Rafel Cortès, also known as Cap loco (Crazy head), remarried a Catholic woman with a converso surname. His family was upset because she wasn't of Jewish ancestry. Feeling hurt, he told the Inquisition about some of his fellow Crypto-Jews. Fearing a general denunciation, a large group planned a mass escape. On March 7, 1688, they secretly boarded an English ship. But bad weather prevented them from leaving, and they had to return home. The Inquisition found out and arrested the entire group.

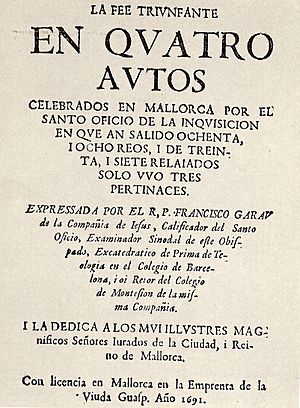

The trials lasted three years. The group's unity weakened due to strict isolation and the feeling that escape was impossible. In 1691, the Inquisition held three autos de fe, condemning 73 people. Of these, 45 were handed over to civil authorities to be burned, and 5 were burned in effigy. Three people who had already died had their bones burned. In total, 37 were actually punished, and three – Rafel Valls, Rafel Benet, and Caterina Tarongí – were burned alive. About 30,000 people watched.

The sentences also included other punishments that lasted for at least two generations: those in the condemned families, their children, and grandchildren could not hold public jobs, become priests, marry non-Xuetes, wear jewelry, or ride horses. While the last two punishments weren't strictly enforced, the others continued due to custom, even beyond the two generations.

The Last Trials

The Inquisition continued to open and close trials, mostly against people who had died. In 1695, one auto de fe was held against 11 deceased people and one living woman who was "reconciled." In the 1700s, there were two individual trials: in 1718, Rafel Pinya confessed and was reconciled. In 1720, Gabriel Cortès, who had fled to Alexandria and returned to Judaism, was burned in effigy as the last person condemned to death by the Majorcan Inquisition.

These last cases were rare. The trials of 1691 marked the end of Crypto-Judaism in Majorca. The escape of leaders, the devastation of the mass burnings, and widespread fear made it impossible to keep the old faith alive. It is after these events that we can truly speak of the Xuetes as a distinct group.

Anti-Xueta Propaganda

Faith Triumphant

In the same year as the 1691 autos de fe, a Jesuit priest named Francesc Garau published a book called Faith Triumphant. This book described the Inquisition trials and was meant to keep the memory and shame of the converts alive. It helped create the reasons for treating Xuetes differently and continued this separation.

The book was republished in 1755 and used to argue against Xuetes having equal rights. It also formed the basis for another book in 1857, The Balearic Synagogue or the history of the Majorcan Jews. In the 20th century, the book was republished many times, but with the opposite intention – to show how harsh and insensitive its original message was.

Les gramalletes

The gramalleta or sambenet (also called sanbenito) was a special tunic that people condemned by the Inquisition had to wear as punishment. The designs on the tunic showed what crime they had committed and their punishment. After the autos-da-fé, a painting of the convicted person wearing the gramalleta was made, with their name included. In Majorca, these paintings were publicly displayed in the cloister of St. Domingo to serve as a lasting reminder of the verdict.

Because these displays wore out, the Inquisition ordered them to be redone several times. This caused problems because many noble families had ancestors among the condemned. However, in 1755, the order was carried out, focusing on sambenets from after 1645, which mostly involved Xuete families. These sambenets remained on display until 1820, when a group of Xuetes attacked and burned St. Domingo.

In 1755, the same year Faith Triumphant was republished, another book was published. It listed the sambenitos that had been displayed and renewed. This book also aimed to ensure people didn't forget the history, despite the efforts of those affected to make it disappear.

The Xueta Community Today

The Inquisition wanted to make Jews disappear by forcing them into the Christian community. But it actually did the opposite: it kept the memory of the condemned alive, and by extension, of everyone with those family names, even if they were sincere Christians. This helped create a community that, even without Jewish practices, stayed very close-knit. Meanwhile, other descendants of Crypto-Jews on the island, who weren't publicly shamed, lost all knowledge of their origins.

Soon after, the Xuetes regained their important role in society. Even though their religious network was gone and their money had been taken, they formed strong business ties with nobles and clergy, even with Inquisition officials. Their renewed energy and political connections allowed them to actively fight for equal rights, adapting to the changing times.

The War of the Spanish Succession (1705-1715)

During the War of the Spanish Succession, some Xuetes supported Philip V of Spain (Bourbon family), hoping he would bring modern ideas about religion and society. They saw the French Bourbon rule as less repressive than the previous Habsburg rule in Spain.

A group of Xuetes, led by Gaspar Pinya, actively supported Philip. In 1711, a plot financed by Pinya was discovered. He was jailed and his property taken. But when the Bourbons won the war, he was rewarded with rights similar to minor nobility. This didn't affect the rest of the community.

The Republication of Faith Triumphant (1755)

In 1755, some Xuetes, including tailor Rafel Cortes, tried to stop the republication of Faith Triumphant. Their request was accepted, and the book's distribution was stopped for a while. However, the Inquisitors eventually allowed it to be distributed again.

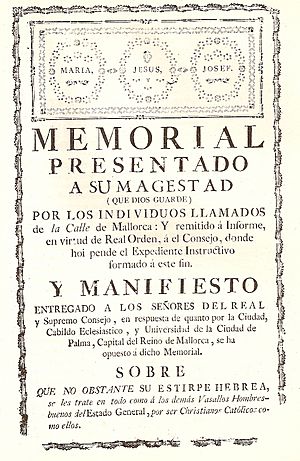

The Carrer Deputies (1773-1788)

In 1773, the Xuetes chose six representatives, known as "perruques" (wigs) because of their fancy wigs, to ask King Charles III of Spain for full social and legal equality. The King asked Majorcan institutions for their opinion, and they strongly opposed the Xuetes' request. A long and expensive legal battle followed, where both sides passionately argued their cases. The documents from this trial show how deep discrimination was, but also how determined the Xuetes were to fight for equality.

In 1782, a prosecutor in Majorca, despite knowing the King might favor the Xuetes, wrote a very racist memo. He suggested stopping the agreement and exiling the Xuetes to Menorca and Cabrera, where they would be kept with strict limits on their freedom.

Finally, the King cautiously sided with the Xuetes. On November 29, 1782, he signed a Real Cédula (Royal Decree). This decree allowed Xuetes freedom to move and live anywhere, removed architectural features that marked the Segell district, and banned insults and mistreatment. The King also seemed open to full professional freedom and allowing Xuetes into the navy and army, but he wanted these changes to happen slowly to avoid more conflict.

Less than six months later, the deputies pushed again for Xuetes to access any job they wanted and reported that insults and discrimination hadn't stopped. They also complained about the sambenets still being displayed. The King set up a group to study the problem. This group suggested removing the sambenets, banning Faith Triumphant, spreading Xuetes throughout the city (even by force if needed), and removing all formal ways they helped each other. They also suggested allowing Xuetes into all church, university, and military jobs, getting rid of guilds, and ending "purity of blood" rules, or at least limiting them to 100 years. These last two suggestions were meant for the whole kingdom.

Then came another period of discussions and a new trial. In October 1785, a second Cédula Real was issued. It mostly ignored the group's suggestions and only allowed Xuetes into the army and civil administration. Finally, in 1788, a last rule established simple equality in holding any office, but still didn't mention university or church positions. That same year, the Court and the Inquisition tried to remove the sambenets from the cloister, but it didn't happen.

The most noticeable effect of these Royal Decrees was the slow breaking up of the Segell community. Xuetes started to live in other streets and neighborhoods. However, those who stayed in Segell kept their social discrimination, marrying only within their group, and continuing traditional jobs. In education and religion, where the King's reforms didn't reach, segregation remained strong.

The End of the Old System (1812-1868)

Majorca was not taken over during the Napoleonic wars. While the new Spanish Constitution of 1812 brought liberal ideas, Majorca became a place for those who strongly supported the old ways. In 1808, soldiers blamed the Xuetes for their mobilization and attacked the Segell district.

The 1812 Constitution, in effect from 1812 to 1814, ended the Inquisition and brought the full civil equality that Xuetes had long wanted. Because of this, many active Xuetes joined the liberal cause. In 1820, when the Constitution was restored, a group of Xuetes attacked the Inquisition headquarters and the Santo Domingo monastery, burning their records and the sambenets. When the Constitution was abolished again in 1823, the Carrer was raided, and shops were looted. Such events were common during this time, similar to riots in other towns on the island.

In 1836, Onofre Cortès became a councilor in the Palma town hall. This was the first time since the 1500s that a Xueta held such a high public office. Since then, it has become common for Xuetes to hold public positions in the town hall and provincial government.

In 1857, a book called The Balearic synagogue or the history of the Jews of Majorca was published. Much of this book repeated Faith Triumphant. A year later, another book, A miracle and a lie. Vindication of the Majorcan Christians of Hebrew lineage, was published in response.

Even though there were different opinions within the Xueta community before the Inquisition trials, it became clear during these violent changes that one small but important group was liberal, later republican, and somewhat against the church. They fought to end all signs of discrimination. Another group, probably the majority but less visible in history, was conservative and very religious. They wanted to go unnoticed. Both groups wanted the "Xueta problem" to disappear, but in different ways: one by showing the injustice, the other by blending in.

During these progressive times, Xuetes formed social clubs and mutual aid groups. They also gained positions in political institutions through liberal parties.

From the First Republic to the Second Republic (1869-1936)

Once they could, some wealthy Xueta families gave their children a good education. These children played an important role in the artistic movements of the time. Xuetes were leaders in the Renaixença (the revival of Catalan culture), defending the Catalan language and bringing back the Floral Games (literary competitions). Important figures included Tomàs Aguiló i Cortès, Marian Aguiló i Fuster, and Ramón Picó i Campamar.

Josep Tarongí (1847–1890), a priest and writer, faced difficulties in his studies but was eventually ordained. Because he was Xueta, he had to work outside Majorca. He was central to a big debate in the 1800s about the Xueta issue. In 1876, he was forbidden to preach at St. Miquel church. This started a public argument that involved many people and had a big impact on and off the island.

Between 1923 and 1930, several Xuetes held the position of mayor of Palma, including Guillem Forteza Pinya, Joan Aguiló Valentí, and Rafel Ignaci Cortès Aguiló.

The short period of the Second Spanish Republic was also important. The state was officially secular (not tied to a religion), and many Xuetes supported this new system, just as their ancestors had supported Enlightenment and liberal ideas. During the Republic, for the first time, a Xueta priest preached a sermon at the Palma cathedral, which was very symbolic.

From the Spanish Civil War to Today (1936-early 21st C.)

Prejudice against Xuetes continued to decrease as Majorca opened up to tourism in the early 1900s and its economy grew. Many outsiders, both Spanish and foreign, moved to the island. For them, the Xuetes' history meant nothing, which marked a turning point for the community.

In 1966, Miguel Forteza Piña published a book called The descendants of the converted Jews of Majorca. Four words of truth. This book revealed research from the 1930s that showed more than 200 Majorcan surnames were linked to those condemned for practicing Judaism. This caused the last big public debate about the Xueta question. After this, discrimination mostly became a private matter, and public expressions of it almost disappeared.

Freedom of religion was legally introduced at the end of the Franco era, though it was limited to private practice. This allowed some Xuetes to reconnect with Judaism. In the 1960s, there were some revival movements. For example, Nicolau Aguiló moved to Israel in 1977 and returned to Judaism, becoming Rabbi Nissan Ben-Avraham.

There's been some mixed feelings between Judaism and the Xuetes. Jewish authorities in Israel have sometimes found it difficult to deal with Jews who have a Christian tradition. But for Xuetes interested in connecting with world Jewry, their unique existence is explained by the fact that they are "Jews." This might explain the existence of a mix of Jewish and Christian worship called Xueta Christianity, though it's a small group. Traditionally, the Church of Saint Eulalia and the Church of Montesión in Palma de Mallorca have been important centers for Xueta religious life.

A significant event after Spain became a democracy was the election of Ramon Aguiló (a direct Xueta descendant) as socialist mayor of Palma in 1979. He was re-elected until 1991. His election by popular vote showed that discrimination was declining. Other cases, like Francesc Aguiló becoming mayor of Campanet, also confirmed this.

However, this doesn't mean all rejection of Xuetes has disappeared. A 2001 poll by the University of the Balearic Islands showed that 30% of Majorcans said they wouldn't marry a Xueta, and 5% said they wouldn't even want Xuetes as friends. While these numbers are high, they are mostly among older people.

In recent years, several Xueta groups have been created, such as RCA-Llegat Jueu ("Jewish Legacy") and the Institut Rafel Valls. The city of Palma has also joined the Red de Juderias de España ("Network of Spanish Jewries"), which connects Spanish cities with a historical Jewish presence.

New immigration in the early 2000s is bringing new energy to the community, including at the Palma synagogue, involving both newcomers and Xuetes. In 2010, Rabbi Nissan Ben-Avraham, a son of the community, returned to Spain after becoming a rabbi in Israel.

Recognition

In 2011, Rabbi Nissim Karelitz, a leading rabbi and Jewish law expert in Bnei Brak, Israel, officially recognized the Chuetas of Palma de Majorca as Jewish.

See also

In Spanish: Chueta para niños

In Spanish: Chueta para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |