1550–1600 in European fashion facts for kids

Fashion in Europe from 1550 to 1600 became much more fancy and rich. Clothes had lots of different fabrics, cuts, embroidery, and decorations. The wide shapes for clothes, which were popular in the 1530s, changed. By the middle of the century, a tall, narrow look with a V-shaped waist was back in style.

Later, sleeves and women's skirts started to get wider again, especially at the shoulders. This wide shoulder look continued into the next century. A very important part of clothing during this time was the ruff. It started as a small ruffle on a shirt collar. But it grew into a separate, large piece of fine linen. Ruffs were often decorated with lace or embroidery and shaped into stiff, neat folds using starch and hot irons.

Contents

General Trends in Fashion

Spanish Style: Dark and Rich

When Charles V gave up his power in 1558, his son Philip II became king of Spain. Even though Europe was no longer ruled by one court, Spain's love for dark, rich clothing became very popular. New friendships and trade routes appeared as Catholic and Protestant countries became more separate.

The strict and formal styles of the Spanish court were popular almost everywhere, except in France and Italy. Black clothes were worn for the most important events. Black dye was hard and expensive to make, so black clothing looked very fancy, even if it seemed simple. Rich Protestants also liked this style.

Clothes were very detailed and made from heavy fabrics like velvet and silk. They were often decorated with bright jewelry like rubies, diamonds, and pearls, which stood out against the dark clothes. Even Queen Elizabeth's clothes showed styles from France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Poland, as well as Spain.

Linen ruffs grew from small frills at the neck and wrists to huge "cartwheel" shapes. By the 1580s, these ruffs needed wire supports to hold them up. Ruffs were worn by everyone in Europe, no matter their social class. They were made from long pieces of linen, sometimes as long as 19 yards! Later ruffs were made from delicate reticella, a type of lace.

Elizabethan Style: Rules and Riches

Because Elizabeth I was Queen of England, women's fashion became very important. The Queen always had to look pure and perfect, and this idea influenced how Elizabethan women dressed.

The Elizabethan era had its own customs and social rules, which were shown in their fashion. Your style often depended on your social status. People had to follow the Elizabethan Sumptuary Laws, which controlled what kind of clothes and materials they could wear.

These sumptuary laws were used to control people's behavior and make sure the social classes stayed in order. Everyone in England knew these rules. If you broke them, you could get big fines, lose your property or title, or even lose your life.

When it came to fabrics, only royalty could wear ermine fur. Other nobles could only wear fox or otter fur. People lower in society could use other animal products for their clothes. Clothes were often padded and stiffened with things like whalebone to create a geometric shape, making the waist look small.

Even the upper classes had rules. Certain materials, like cloth of gold, could only be worn by the Queen, her mother, children, aunts, and sisters, as well as duchesses and countesses. Other noblewomen, like viscountesses, were not allowed to wear it.

Not just fabrics, but also colors were restricted in the Elizabethan era, depending on your social status. Only the Queen and her direct family could wear purple. Depending on your status, a color might be allowed for a whole outfit or only for specific items like cloaks or jackets. Lower classes could only use brown, beige, yellow, orange, green, gray, and blue in wool, linen, and sheepskin. Upper classes usually wore silk or velvet.

Fabrics and Decorations

Clothes in the Elizabethan Era were often heavily decorated, especially for rich people in England. Shirts and undershirts were embroidered with blackwork (black stitching) and had lace edges. Heavy velvet and brocade fabrics were decorated even more with bobbin lace, gold and silver embroidery, shiny sequins, and jewels. Towards the end of this time, colorful silk embroidery became very popular. It was a way for rich people to show off their wealth.

The trend for darker, more serious colors might have come from Spain and its fine merino wool. Countries like the Netherlands, Germany, Scandinavia, England, France, and Italy all started to use the formal Spanish style after the 1520s. Expensive dyes could create many colors, from blacks and grays to browns, purples, and reds. Cheaper reds, oranges, and pinks came from plants like madder, and blues from woad. Other plants made yellow dyes, but these often faded.

By the end of this period, there was a clear difference between the serious styles liked by Protestants in England and the Netherlands (which still showed Spanish influence) and the lighter, more revealing styles of the French and Italian courts. This difference continued into the 17th century.

Women's Fashion

Women's outer clothes usually included a loose or fitted gown worn over a kirtle or petticoat (or both). Instead of a gown, a woman might wear a short jacket or a doublet with a high neckline. The "trumpet" sleeves, which were wide at the cuff and popular in the 1540s and 1550s, disappeared by the 1560s. Narrower French and Spanish sleeves became popular.

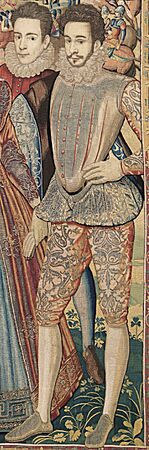

Overall, the shape of clothes was narrow in the 1560s. Then, it slowly became wider, with a focus on the shoulders and hips. The slashing technique, where fabric was cut to show a contrasting lining, changed. By the 1580s in England, these cuts became padded and jeweled shoulder rolls.

Gown, Kirtle, and Petticoat

The main outer garment was a gown. Gowns came in many styles: loose or fitted (called a French gown in England); with short or long sleeves; and floor-length or with a long train (clothing).

The gown was worn over a kirtle or petticoat (or both for warmth). Before 1545, the kirtle was a fitted one-piece garment. After that, kirtles or petticoats might have attached bodices that fastened with lacing or hooks. Most had sleeves that were pinned or laced on. The parts of the kirtle or petticoat that showed under the gown were usually made of richer fabrics, especially the front panel of the skirts.

The bodices in French, Spanish, and English styles were stiffened into a cone or a flat, triangular shape. They ended in a V-shape at the front of the waist. Italian fashion was different, with a broad U-shape instead of a V. Spanish women also wore stiff, boned corsets called "Spanish bodies." These squeezed the body into a smaller, but still geometric, cone shape. Bodices could have high necks or wide, low, square necklines. They fastened with hooks in front or laced up the side-back. High-necked bodices, like men's doublets, might fasten with hooks or buttons. Italian and German fashion kept the front-laced bodice from earlier times, with ties in parallel rows.

Underwear

During this time, women's underwear was a washable linen chemise or smock. This was the only piece of clothing worn by every woman, no matter her social class. Rich women's smocks were embroidered and trimmed with narrow lace. Smocks were made from rectangular pieces of linen. In northern Europe, the smock fit closely and was widened with triangular pieces of fabric. In Mediterranean countries, smocks were cut fuller in the body and sleeves. High-necked smocks were worn under high-necked outer clothes to protect the expensive garments from body oils and dirt.

Stockings or hose were usually made of woven wool sewn to fit. They were held up with ribbon garters.

The first corsets probably came from Spain in the 16th century. They were like stiff bodices made with thick fabrics. This fashion spread to Italy, then to France, and eventually to England. In England, it was called a pair of bodies because it was made in two parts that laced front and back. The corset was only for rich people. It was a fitted bodice stiffened with reeds, wood, or whalebone.

Skirts were held in their proper shape by a farthingale or hoop skirt. In Spain, the cone-shaped Spanish farthingale stayed popular into the early 17th century. It was only briefly fashionable in France, where a padded roll called a French farthingale (or bum roll in England) held the skirts out in a rounded shape at the waist. The skirts then fell in soft folds to the floor. In England, the Spanish farthingale was worn through the 1570s, then slowly replaced by the French farthingale. By the 1590s, skirts were pinned to wide wheel farthingales to create a drum shape.

Partlet

A low neckline might be filled in with an infill called a partlet. Partlets worn under the kirtle and gown were usually made of lawn (a fine linen). Partlets were also worn over the kirtle and gown. The colors of "over-partlets" varied, but white and black were most common. The partlet might be made of the same material as the kirtle and decorated with lace. Embroidered partlet and sleeve sets were often given to Queen Elizabeth as New Year's gifts.

Outerwear

Women wore strong overskirts called safeguards over their dresses when riding or traveling on dirty roads. Hooded cloaks were worn in bad weather. Sometimes, strings were attached to the stirrup to hold the skirts in place while riding. Mantles were also popular. These were like square blankets or rugs attached to the shoulder, worn around the body, or on the knees for extra warmth.

Besides keeping warm, Elizabethan cloaks were useful for any weather. The Cassock, also known as the Dutch cloak, was another type of cloak. Its name suggests military ideas, and it had many forms. This cloak was known for flaring out at the shoulders and having detailed decorations. Cloaks could be ankle-length, waist-length, or shorter. They also had specific measurements, often cut 3/4 length. Longer cloaks were more popular for travel and came with many options, like taller collars, upturned collars, or no collars, and sleeves.

The French cloak was quite different from the Dutch one. It was worn anywhere from the knees to the ankle. It was usually worn over the left shoulder and included a cape that reached the elbow. It was a very decorated cloak. The Spanish cloak or cape was known for being stiff, having a very decorated hood, and being worn to the hip or waist. Women's over-gowns were very plain and worn loosely to the floor or ankle length. The Juppe was related to the safeguard and was usually worn with it. The Juppe replaced the Dutch Cloak and was likely a loose form of the doublet.

Accessories

The fashion for wearing or carrying the pelt of a sable or marten spread from Europe to England. These accessories are called zibellini or "flea furs." The most expensive zibellini had faces and paws made of gold with jeweled eyes. Queen Elizabeth received one as a New Year's gift in 1584. Gloves made of perfumed leather had embroidered cuffs. Folding fans appeared late in this period, replacing flat fans made of ostrich feathers.

Jewelry was also popular for those who could afford it. Necklaces were made of beaded gold or silver chains and worn in concentric circles, sometimes reaching as far down as the waist. Ruffs also had jewelry attached, like glass beads, embroidery, gems, brooches, or flowers. The jewels of Mary, Queen of Scots are well-known.

Belts were surprisingly important. They were used for fashion or for practical reasons. Lower classes wore them almost like tool belts. Upper classes used them as another place to add jewels and gems. Scarves, though not often mentioned, had a big impact on Elizabethan style. They were multi-purpose. They could be worn on the head to protect pale skin from the sun, warm the neck on a cold day, and add to the colors of a gown or outfit. The upper class had silk scarves of every color to brighten an outfit, often with gold thread and tassels.

When traveling, noblewomen would wear oval masks of black velvet called visards to protect their faces from the sun.

Hairstyles and Headgear

Married and adult women covered their hair, just like in earlier times. Early in this period, hair was parted in the middle and fluffed over the temples. Later, front hair was curled and puffed high over the forehead. Wigs and fake hairpieces were used to make hair look longer or fuller.

A typical hairstyle of the period involved curling the front hair. The back hair was worn long, twisted with ribbons, then coiled and pinned up.

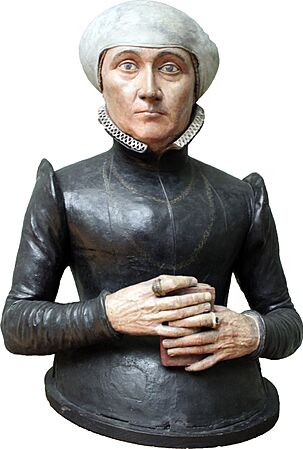

A close-fitting linen cap called a coif or biggins was worn, either alone or under other hats or hoods, especially in the Netherlands and England. Many embroidered and lace-trimmed English coifs from this period still exist.

The French hood was worn throughout this period in both France and England. Another popular head covering was a caul, which was a net cap lined with silk and attached to a band. It covered pinned-up hair. This style was also seen in Germany earlier in the century. Widows wore black hoods with thin black veils for mourning.

Makeup

The ideal beauty standard for women in the Elizabethan era was to have light or naturally red hair, a pale complexion, and red cheeks and lips. This was inspired by Queen Elizabeth's style. The goal was to look very "English," especially since Spain, with its darker-haired people, was England's main rival.

To make their skin even paler, women wore white makeup on their faces. This makeup, called Ceruse, was made of white lead and vinegar. While it made skin look pale, the white lead was poisonous. Women often got lead poisoning from it, which could make them very sick or even lead to death before age 50. Other ingredients used in makeup included sulfur, alum, and tin ash. Besides makeup, women sometimes had blood removed to make their faces look paler.

Cochineal, madder, and vermilion were used as dyes to create bright red effects on the cheeks and lips. Kohl was used to darken eyelashes and make eyes look bigger.

Style Gallery 1550s

Style Gallery 1560s

Style Gallery 1570s

Style Gallery 1580s

Style Gallery 1590s

Men's Fashion

Overview of Men's Clothing

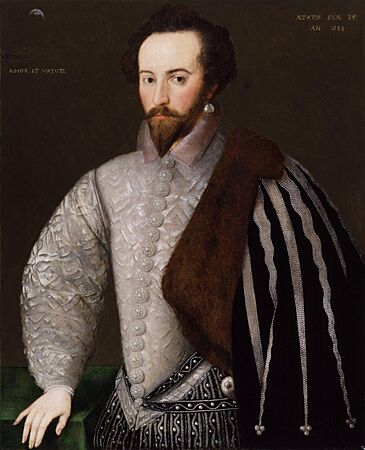

Men's fashionable clothing included a linen shirt with a collar or ruff and matching wrist ruffs. These were starched to keep them stiff and bright. Over the shirt, men wore a doublet with long sleeves sewn or laced on. Doublets were stiff, heavy garments, often reinforced with boning. Sometimes, a jerkin, usually sleeveless and made of leather, was worn over the doublet. During this time, doublets and jerkins became more colorful and highly decorated. Waistlines dipped into a V-shape in front and were padded to hold their shape. Around 1570, this padding became very big, creating a peascod belly (like a pea pod).

Hose, which were like pants, came in many styles. They were worn with a codpiece early in the period. Trunk hose or round hose were short, padded pants. Very short trunk hose were worn over cannions, which were fitted hose that ended above the knee. Trunk hose could be paned or pansied, meaning they had strips of fabric (panes) over a full inner layer. Slops or galligaskins were loose hose that reached just below the knee. Slops could also be pansied.

Pluderhosen were a type of pansied slops from Northern Europe. They had a very full inner layer that pulled out between the panes and hung below the knee.

Venetians were semi-fitted hose that reached just below the knee.

Men wore stockings or netherstocks and flat shoes with rounded toes. Early in the period, shoes had cuts, and later they had ties over the top of the foot. Boots were worn for riding.

Outerwear for Men

Short cloaks or capes, usually hip-length, often with sleeves, or military jackets like a mandilion, were fashionable. Long cloaks were worn in cold and wet weather. Gowns were becoming old-fashioned and were mostly worn by older men for warmth indoors and out. During this time, robes started to become special clothing for certain jobs, like scholars (think of graduation gowns today).

Hairstyles and Headgear for Men

Hair was usually worn short, brushed back from the forehead. Longer styles were popular in the 1580s. In the 1590s, fashionable young men wore a lovelock, which was a long section of hair hanging over one shoulder.

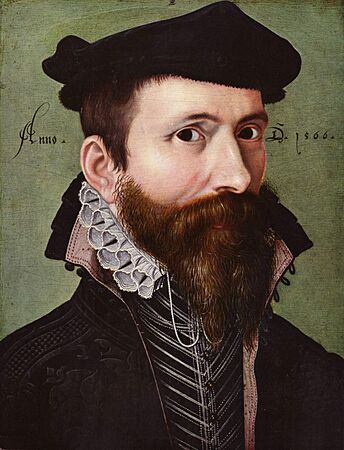

Through the 1570s, men wore a soft fabric hat with a gathered top. These came from the flat hat of earlier times. Over time, the hat became stiffer, and the top became taller and less flat. Later, a cone-shaped felt hat with a rounded top called a capotain or copotain became popular. These hats became very tall towards the end of the century. Hats were decorated with a jewel or feather and were worn indoors and out.

Close-fitting caps that covered the ears and tied under the chin, called coifs, continued to be worn by children and older men under their hats or alone indoors. Men's coifs were usually black.

A cone-shaped linen cap with a turned-up brim called a nightcap was worn informally indoors. These were often embroidered.

Beards

Even though many men wore beards before the mid-16th century, this was when grooming and styling facial hair became socially important. These styles changed very often, from pointed whiskers to round trims. The easiest way for men to keep their beard style was to apply starch to their groomed faces. Popular beard styles at this time included:

- The Cadiz Beard or Cads Beard: Named after the Cádiz Expedition in 1596. It looked like a large, bushy growth on the chin.

- The Goat Beard: Looked like a goatee. It was similar to the Pick-a-devant and Barbula styles.

- The Peak: A common name for a beard, but it specifically meant a mustache neatly styled to a pointed tip.

- The Pencil Beard: A small, thin part of the beard coming to a point around the center of the chin.

- The Stiletto Beard: Shaped like the dagger it was named after.

- The Round Beard: Trimmed to emphasize the roundness of the male cheekbones. Another name for this was the Bush Beard.

- The Spade Beard: Shaped like a spade from a deck of cards. The beard was wide on the upper cheeks and curved down to a point at the chin. This style was thought to look military and was liked by soldiers.

- The Marquisetto: A very sleek beard trim, cut close to the chin.

- The Swallow's Tail Beard: Unique because the hairs from the center of the chin were separated and spread in opposite directions. It was a longer, more noticeable version of the forked beard.

Accessories for Men

A baldrick or "corse" was a belt often worn diagonally across the chest or around the waist. It was used for holding items like swords, daggers, bugles, and horns.

Gloves were often used to show wealth. Starting in the second half of the 16th century, many men cut off the tips of their glove fingers so that people could see the jewels hidden by the glove.

Late in this period, fashionable young men wore a plain gold ring, a jeweled earring, or a strand of black silk through one pierced ear.

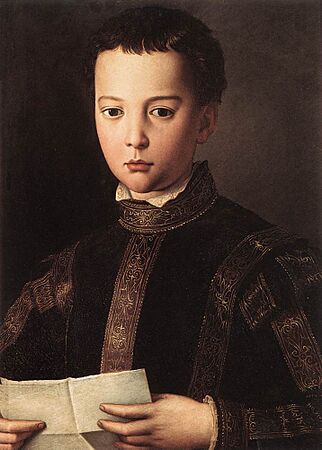

Style Gallery 1550s–1560s

-

King Edward VI of England, c. 1550.

-

King Eric XIV of Sweden, c. 1560.

-

Portrait of Henry Lee of Ditchley, 1568.

Style Gallery 1570s

Style Gallery 1580s–1590s

-

King Johan III of Sweden, 1582.

Footwear

Fashionable shoes for men and women were similar. They had a flat, one-piece sole and rounded toes. Shoes were fastened with ribbons, laces, or simply slipped on. Shoes and boots became narrower, fit the foot more closely, and covered more of the foot, sometimes up to the ankle. Like in the first half of the century, shoes were made from soft leather, velvet, or silk. In Spain, Italy, and Germany, the slashing of shoes (making cuts in the fabric) continued. In France, however, slashing slowly went out of style, and coloring the soles of shoes red began. Besides slashing, shoes could be decorated with cords, quilting, and frills.

Thick-soled pattens were worn over delicate indoor shoes to protect them from dirty streets. A type of patten popular in Venice was the chopine – a platform-soled shoe that could raise the wearer as high as two feet off the ground!

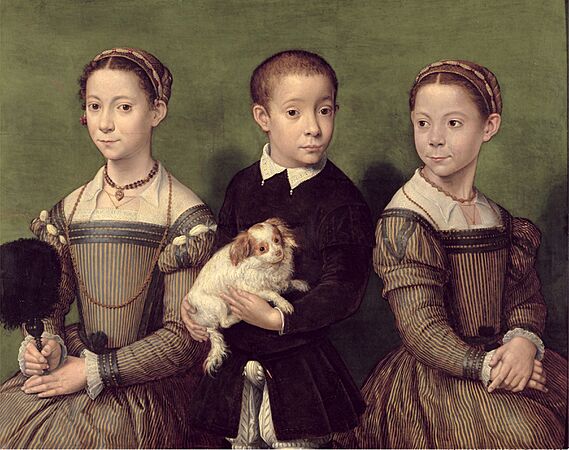

Children's Fashion

Young boys wore gowns or skirts and doublets until they were breeched, which meant they started wearing breeches (pants) like adult men.

-

The sisters of Sofonisba Anguissola, Italy, 1555.

-

The French princess Marguerite of Valois, 1560.

Working Class Clothing

-

German painting of the Last Supper in contemporary dress, 1565.

|

See also

- Blackwork

- Coif

- Doublet

- Elizabethan era

- Farthingale

- Hose

- Jerkin

- Ruff

- Zibellino

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |