1920 Nebi Musa riots facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 1920 Jerusalem riots |

|

|---|---|

| Part of Intercommunal conflict in Mandatory Palestine | |

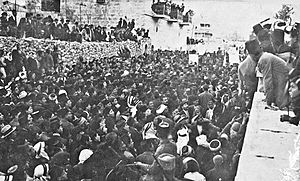

Nebi Musa procession, 4 April 1920

|

|

| Location | Jerusalem, Palestine |

| Coordinates | 31°47′0″N 35°13′0″E / 31.78333°N 35.21667°E |

| Date | 4–7 April 1920 |

|

Attack type

|

Riot |

| Deaths | 5 Jews, 4 Arabs |

|

Non-fatal injuries

|

216 Jews, 18 Arabs, 7 Britons |

The 1920 Nebi Musa riots or 1920 Jerusalem riots were a series of violent events. They happened in the British-controlled area of Palestine from Sunday, April 4, to Wednesday, April 7, 1920. The riots took place in and around the Old City of Jerusalem.

During these events, five Jewish people and four Arab people were killed. Several hundred others were hurt. The riots happened at the same time as the Nebi Musa festival. This was an important Muslim festival held every year around Easter Sunday. The riots were named after this festival.

The violence followed a time of growing tension between Arab and Jewish communities. These events also happened shortly after the Battle of Tel Hai. They came as Arab groups in Syria faced increasing pressure during the Franco-Syrian War.

During the Nebi Musa festival, many Muslim people gathered for a religious parade. Arab religious leaders gave speeches. These speeches mentioned Zionist immigration and earlier fights near Jewish villages in the Galilee. It is not fully clear what exactly caused the parade to turn into a riot.

The British military government in Palestine was criticized for how it handled the situation. People said they pulled troops out of Jerusalem too soon. They were also slow to get control back. Because of the riots, trust between the British, Jewish, and Arab communities weakened. One result was that the Jewish community started to build its own security groups. These groups worked alongside the British administration.

After the riots, leaders (sheikhs) from 82 villages near Jerusalem and Jaffa spoke out. They said they represented 70% of the local people. They signed a paper protesting the violence against Jewish people. Some people believe these statements might have been influenced by money. Even with the riots, the Jewish community in Palestine held elections. These elections for the Assembly of Representatives took place on April 19, 1920. They were held everywhere except Jerusalem, where they were delayed until May 3. The riots also happened before the San Remo conference. This meeting, held from April 19 to 26, 1920, decided the future of the Middle East.

Contents

What Led to the Riots

After World War I, the Ottoman Empire fell apart. Great Britain and France took on a role to help the Middle East. The Balfour Declaration of 1917 said that a homeland for the Jewish people should be created in Palestine. The Paris Peace Conference, 1919 also discussed these plans. Both Jewish and Arab groups talked a lot about these ideas. News about these talks was widely shared.

The idea of self-determination means people should choose their own government. The League of Nations supported this idea. However, it was not fully applied to Palestine. This was because the British knew that local people would likely not support Zionism, which the British backed. These plans for Palestine and other Arab areas after World War I made many Arab people more upset and active.

On March 1, 1920, Joseph Trumpeldor was killed. This happened during the Battle of Tel Hai by a group from Southern Lebanon. This worried Jewish leaders a lot. They asked the British military government to protect the Yishuv (Jewish community). They also asked them to stop a pro-Syrian public gathering.

However, British leaders like General Louis Bols and Military Governor Ronald Storrs did not take these fears seriously. This was despite a warning from Chaim Weizmann, head of the Zionist Commission. Weizmann said that a "pogrom is in the air," meaning a violent attack on Jews was likely. There were also warnings about possible trouble between Arabs, and between Arabs and Jews. To Weizmann, these warnings sounded like those given before attacks on Jews in Russia.

At the same time, Arab hopes grew high. On March 7, the Syrian Congress declared the independence of Greater Syria. This new Kingdom of Syria, with Faisal as its king, claimed the British-controlled area of Palestine. On March 7 and 8, protests happened in all cities of Palestine. Shops closed, and many Jewish people were attacked. Protesters shouted things like "Death to Jews" and "Palestine is our land and the Jews are our dogs!"

Jewish leaders asked the British to let Jewish defenders carry weapons. This was to make up for the lack of British troops. This request was turned down. But Ze'ev Jabotinsky and Pinhas Rutenberg openly started training Jewish volunteers for self-defense. The Zionist Commission kept the British informed about this. Many volunteers were from the Maccabi sports club. Some were veterans of the Jewish Legion. Their training mostly involved exercises and hand to hand combat with sticks. By the end of March, about 600 people were doing military drills daily in Jerusalem. Jabotinsky and Rutenberg also started collecting weapons.

The Nebi Musa festival was an annual Muslim spring festival. It started on the Friday before Good Friday. It included a parade to the Nebi Musa shrine (tomb of Moses) near Jericho. This festival had been celebrated since the time of Saladin. An Arab writer, Khalil al-Sakakini, described how groups would come with banners and weapons. The Ottoman Turks used to send thousands of soldiers and even cannons to keep order during the Nebi Musa parade in Jerusalem's narrow streets. However, Governor Storrs only sent 188 police officers, even after warning Arab leaders.

Days of Trouble in Jerusalem

By 10:30 a.m. on Sunday, April 4, 1920, between 60,000 and 70,000 Arab people had gathered in the city square for the Nebi Musa festival. Groups had already been attacking Jewish people in the Old City's narrow streets for over an hour.

Amin al-Husayni gave a speech from the Arab Club balcony. His speech was strongly anti-Zionist. His uncle, Musa al-Husayni, who was the mayor, also spoke from the city hall balcony with similar ideas. However, according to one witness, Fayyad al-Bakri, the rioting began when a Jewish person spat on a banner he was holding. When that person was pushed away, Jewish bystanders started throwing stones.

The editor of the newspaper Suriya al-Janubia, Aref al-Aref, also spoke at the Jaffa Gate. What he said is debated. Some say he told people, "If we don't use force against the Zionists and against the Jews, we will never be rid of them." Others say he worked with the police and spoke against violence.

The crowd reportedly shouted "Independence! Independence!" and "Palestine is our land, the Jews are our dogs!" Arab police officers joined in the applause, and the violence began. The local Arab people looted the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem. The Torath Chaim Yeshiva was attacked. Torah scrolls were torn and thrown on the floor, and the building was then set on fire. In the next three hours, 160 Jewish people were injured.

Khalil al-Sakakini saw the violence start in the Old City. He wrote about people running, stones being thrown at Jews, shops closing, and screams. He saw a Jewish shoeshine boy being beaten. He heard people shout, "Muhammad's religion was born with the sword." He felt sickened by the "madness of humankind."

The army put a night curfew in place on Sunday night. They arrested several dozen rioters. But on Monday morning, these rioters were allowed to go to morning prayers and then were released. Arab people continued to attack Jewish people and break into their homes, especially in buildings where both Arabs and Jews lived.

On Monday, as the problems got worse, the army closed off the Old City. No one was allowed to leave. Several homes were set on fire, and tombstones were broken. British soldiers found that most illegal weapons were hidden on Arab women. On Monday evening, the soldiers were taken out of the Old City. A later report called this a "mistake." Even with strict rules (martial law), it took the British authorities another four days to bring order back.

The Jewish community in the Old City had no training or weapons. Jabotinsky's men were outside the walled Old City and blocked by British soldiers. Two volunteers managed to get into the Jewish Quarter. They pretended to be medical workers. They helped organize self-defense using rocks and boiling water.

In the riots, five Jewish people and four Arab people died. Two hundred sixteen Jewish people were injured, 18 of them seriously. Twenty-three Arab people were injured, one seriously. About 300 Jewish people were moved out of the Old City for safety.

Questions About British Actions

In Hebrew, these events were called meoraot, meaning targeted attacks. This word reminded people of attacks that often happened in Russia. Palestinian Arabs, however, called them a heroic sign of an 'Arab Revolt'. When people used the word "pogrom" to describe the violence, it suggested that the British government had secretly allowed the anti-Jewish riot to happen. This word compared the events to attacks in Eastern Europe, where Jews were victims of racist violence supported by the rulers.

Soon after, Chaim Weizmann and British army Lieutenant Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen claimed that Haj Amin al-Husseini was encouraged to start the riot by Colonel Bertie Harry Waters-Taylor, who was Field-marshal Allenby's Chief of Staff. The idea was to show the world that Arabs would not accept a Jewish homeland in Palestine. This claim was never proven, and Meinertzhagen was later removed from his position.

The Zionist Commission noted that before the riots, Arab milkmen started asking Jewish customers in Meah Shearim to pay them right away. They said they would no longer serve the Jewish neighborhood. Christian shopkeepers had marked their shops with a cross beforehand so they would not be accidentally looted. An earlier report also accused Governor Storrs of making Arabs angry. It blamed him for stopping efforts to buy the Western Wall. A petition from American citizens to their consul complained that the British had stopped Jews from defending themselves.

After the violence began, Ze'ev Jabotinsky met Governor Storrs. He offered to use his volunteers, but Storrs said no. Storrs took Jabotinsky's pistol and asked where his other weapons were, threatening to arrest him. Later, Storrs changed his mind and asked for 200 volunteers to report to the police station to become deputies. After they arrived and the swearing-in began, orders came to stop, and he sent them away. Arab volunteers had also been invited and were also sent away.

On Sunday night, the first day of the riots, several dozen rioters were arrested. But on Monday morning, they were allowed to go to morning prayers and then were released. On Monday evening, after strict rules (martial law) were put in place, the soldiers were taken out of the Old City. A later report called this a "mistake."

After the riots, Storrs visited Menachem Ussishkin, the new head of the Zionist Commission. Storrs said he felt "regrets for the tragedy that has befallen us." Ussishkin asked, "What tragedy?" Storrs replied, "I mean the unfortunate events that have occurred here in the recent days." Ussishkin then suggested, "His excellency means the pogrom." When Storrs hesitated to call it a pogrom, Ussishkin said, "You Colonel, are an expert on matters of management and I am an expert on the rules of pogroms."

The Palin Report noted that Jewish representatives kept calling the events a "pogrom." This suggested that the British government had allowed the violence to happen.

Looking Into the Riots

The Palin Commission (or Palin Court of Inquiry) was a group sent to the region in May 1920 by the British. They looked into the reasons for the trouble.

The Palin Report about the April riots was signed in July 1920. This was after the San Remo conference and after the British military government was replaced by a civilian leader, Sir Herbert Samuel. The report was given in August 1920 but was never officially published. It criticized both sides.

The report blamed the Zionists. It said their "impatience to achieve their ultimate goal and indiscretion are largely responsible for this unhappy state of feeling." It specifically mentioned Amin al-Husayni and Ze'ev Jabotinsky. However, it wrongly identified Jabotinsky as the organizer of the "Bolshevist" (communist) Poalei Zion party, which he was not.

The report also criticized some actions of the British military command. It especially pointed out the decision to pull troops out of Jerusalem early on Monday morning, April 5. It also said that once strict rules (martial law) were announced, the British were slow to regain control.

What Happened Next

More than 200 people were put on trial because of the riots, including 39 Jewish people. Musa Kazim al-Husayni was replaced as mayor by Ragheb Bey Nashashibi, from a rival family. Amin al-Husayni and Aref al-Aref were arrested for causing trouble. But when they were let out on bail, they both escaped to Syria. A military court sentenced them to 10 years in prison in their absence.

Leaders (sheikhs) from 82 villages in the Jerusalem and Jaffa areas publicly protested the Arab riots. They issued a formal statement saying that, in their view, Jewish settlement was not a danger to their communities. Similar statements were sent to London in 1922. Hundreds of sheikhs and local leaders (mukhtars) supported Jewish immigration. They believed that this immigration would improve the lives of Arabs as industries grew, just as the Zionist movement claimed. However, some of these sheikhs were paid by the World Zionist Organisation to make these statements.

British soldiers were sent to search Jewish people for weapons. This was done at the request of the Palestinian Arab leadership. They searched the offices and homes of Chaim Weizmann, the head of the Zionist Commission, and Jabotinsky. At Jabotinsky's house, they found three rifles, two pistols, and 250 rounds of ammunition. Nineteen men were arrested. Jabotinsky went to the jail himself to insist on his arrest. A military judge released him because he was not home when the guns were found. But he was arrested again a few hours later.

Jabotinsky was found guilty of having the pistol that Storrs had taken on the first day of the riot, among other things. The main witness was Ronald Storrs, who said he "did not remember" being told about the self-defense group. Jabotinsky was sentenced to 15 years in prison and sent to Egypt. But the next day, he was returned to Acre Prison.

Jabotinsky's trial and sentence caused a big uproar. Newspapers in London, including The Times, protested it. It was also questioned in the British Parliament. Even before the newspaper articles appeared, General Congreve, the commander of British forces, wrote that Jewish people were sentenced much more harshly than Arab people who had committed worse crimes. He reduced Jabotinsky's sentence to one year. The other 19 Jewish people arrested with him had their sentences reduced to six months.

The new civilian government, led by Herbert Samuel, gave a general pardon (amnesty) in early 1921. However, Amin al-Husayni and Aref al-Aref were not included in the pardon because they had run away before their convictions. Samuel pardoned Amin in March 1921 and made him Mufti of Jerusalem. When the Supreme Muslim Council was created the next year, Husseini demanded and received the title Grand Mufti, a job he would hold for life. Also, General Storrs became the civil governor of Jerusalem under the new government.

As the riots began, the British temporarily stopped Jewish immigration to Palestine. Also, feeling that the British were not willing to defend Jewish settlements from Arab attacks, Palestinian Jews created self-defense groups. These groups became known as the Haganah ("defense"). Furthermore, the riots made the feeling of Palestinian nationalism stronger within the Palestinian Arab community.

See also

- Arab nationalism

- Palestinian nationalism

- Killing of Moshe Barsky, 1913 - the first kibbutz member killed in Arab attack

- Anti-Zionism

- Timeline of Jewish History

- Intercommunal conflict in Mandatory Palestine

Images for kids

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |