Agustín de Zárate facts for kids

Agustín de Zárate (born around 1514 in Valladolid, died around 1575 in Seville) was an important Spanish official, writer, and historian. He worked for the Spanish government and wrote a famous book called Historia del descubrimiento y conquista del Perú (History of the Discovery and Conquest of Peru).

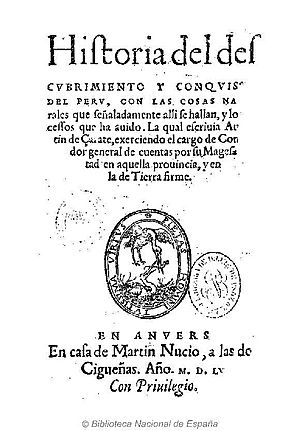

His book tells the story of the first years after the Spanish arrived in the Inca Empire. It covers the time when the Spanish took control and even a civil war among the Spanish leaders. Many people think it is one of the best historical accounts from the Spanish colonization of the Americas. The book was first printed in 1555 and became very popular. It was even translated into English, French, Italian, and German, making it a "best seller" of the 1500s!

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Family

Agustín de Zárate was born around 1514 in Valladolid, a major city in Spain. His family had strong connections to the royal family. He was the only son of Lope Diaz de Zárate and Isabel de Polanco.

His father was a government secretary for important councils. In 1512, he became secretary of the Council of Castile. This was the highest court and administrative body in Spain at the time. When Agustín was about eight years old, his father arranged for him to take over this job when he turned eighteen.

So, in 1532, Agustín became secretary of the Council of Castile. He married Catalina de Bayona, who came from a wealthy family. She brought him a large dowry, which was like a gift of money or property.

In 1538, Agustín's father passed away. Agustín received a good amount of money and property from his inheritance. He also received all of his father's books and weapons. This collection of books helped Agustín learn a lot, even though he didn't go to a formal university. His writings show he loved reading humanistic works, which were popular at the time.

Mission to South America

During the 1500s, a lot of gold and silver was found in Hispanic America. The Spanish king, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, wanted to make sure the government was getting its fair share. He also wanted to protect the indigenous peoples of the Americas. So, he created new laws in 1542 to limit the power of the Spanish settlers, called encomenderos, who controlled groups of native people.

To help manage the money and enforce these new laws, the king decided to send financial auditors to America. Agustín de Zárate was chosen for this important job. He was picked by Philip II of Spain, who was then a prince. Zárate was to check the royal finances in Peru and Tierra Firme (parts of Panama and Colombia).

In August 1543, Zárate left his job as secretary of the Council of Castile. He became the chief accountant for these territories. His job was to make sure the Crown's taxes (usually one-fifth of all income) were paid correctly. He also had to check the accounts in Tierra Firme on his way to Peru.

Zárate left Spain on November 3, 1543. He sailed with a large fleet of 52 ships, led by the first viceroy of Peru, Blasco Núñez Vela. Zárate traveled with friends and family, including his nephews Polo de Ondegardo and Diego de Zárate.

He arrived in Nombre de Dios, Panama, on January 9, 1544. He immediately began checking the financial records there. He reached Lima, Peru, on June 26, 1544. This was just as a big uprising by the encomenderos was starting.

Zárate found that the royal treasury accounts in Lima were very messy. He decided to re-examine all the records from the beginning of the Spanish conquest. This made some royal officials unhappy, as they didn't like his strict audit.

Peru Civil War

The main goal of Viceroy Núñez Vela was to enforce the New Laws. But the encomenderos did not like these laws because they limited their power. They started a rebellion in Cusco, choosing Gonzalo Pizarro as their leader. Gonzalo was the brother of Francisco Pizarro, who had led the conquest of Peru.

The viceroy became very unpopular. The judges of the Royal Tribunal in Lima decided to remove him. They sent him away to Spain. They also stopped enforcing the New Laws and told Gonzalo Pizarro to disband his army.

During the viceroy's trial, Zárate was called as a witness. He said that many people, both Spanish and native, complained about the viceroy's rule. To protect himself, Zárate signed a letter in September 1544. He stated that anything he did regarding the viceroy's removal was due to "just fear."

The Royal Tribunal sent Zárate to tell Gonzalo Pizarro to disband his army. Zárate was chosen because he was a royal servant and a smart man. But when Zárate met Gonzalo, he was afraid to deliver the order. Instead, Gonzalo asked Zárate to present the rebels' demands to the Royal Tribunal in Lima.

Zárate returned to Lima and told the Tribunal that the rebels wanted Gonzalo Pizarro to be named governor. Otherwise, his troops would attack Lima. The judges were unsure, but Zárate supported Gonzalo's appointment. He handed Gonzalo the document making him governor. Years later, Zárate said he did this because his family and friends were held hostage.

Zárate tried to continue his accounting work. But he faced difficulties because royal officials did not want him to examine the poorly managed finances. Gonzalo Pizarro also used a lot of royal money to support his rebellion. He even offered Zárate servants from his own lands. This might suggest Zárate helped Pizarro get royal funds.

Because he could not do his job properly, Zárate decided to return to Spain. Before leaving, he stored his accounting papers in a convent.

Return to Spain

Zárate left the port of Callao on July 9, 1545, about a year after he arrived in Peru. He left his nephews and main assistant behind. He carried a small amount of money he had collected for the Spanish Crown.

He arrived in Panama on August 4, 1545. There, a rebellion supporting the former Viceroy Núñez Vela was still happening. Zárate was asked to provide money for this uprising. He secretly left during the night and reached Nombre de Dios.

In Nombre de Dios, he prepared documents to protect himself from future problems. He wrote a report for the king explaining why he returned without finishing his audit. This report was an early version of his famous book.

He finally left South America on November 9, 1545. His ship was wrecked in a storm in the Caribbean Sea. Zárate ended up in Mexico City, where he was asked to carry more money to Spain. He landed in Spain in July 1546.

Meanwhile, complaints about Zárate had reached the Spanish Court. He was accused of financial mismanagement and supporting Gonzalo Pizarro's rebellion. He was sent to prison. He argued that he was trying to find a middle ground between the rebels and the king. He was released after ten months, thanks to his friends who paid his bail. During this time, Zárate began writing his book, Historia del descubrimiento y conquista del Perú.

After Gonzalo Pizarro's rebellion was defeated in 1548, a new trial started against his supporters. Zárate was accused again and imprisoned for three months. He was later acquitted of the serious charges. However, he had to pay a fine for some financial issues.

In 1554, Prince Regent Philip asked Zárate to collect gold and silver from America. Zárate collected a huge amount of money in less than two months and brought it to the prince.

Zárate's book was ready by then. He gave the manuscript to Prince Philip, who read it during a journey to England. The prince liked the story so much that he asked Zárate to publish it. Zárate was then sent to Antwerp to collect taxes and mint coins.

On March 30, 1555, Zárate signed the dedication letter for his book. The first edition was printed in Antwerp. From then on, his book became widely known, with many reprints and translations.

After his work in Flanders, Zárate returned to Spain. He continued to work as an accountant for the government. In 1574, he was given a new job managing salt mines in Andalusia.

Zárate also made changes to his book. He rewrote parts about important events, like the murder of Francisco Pizarro. He also removed some chapters about the religion of the Native Americans.

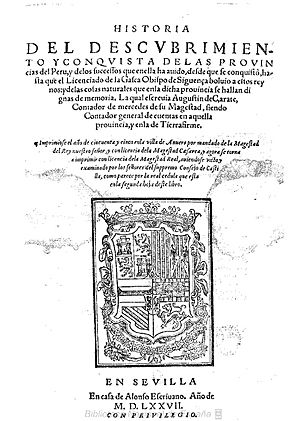

With the king's permission, he published a second edition of his History in Seville in 1577. This version is the one commonly used today.

In his later years, Zárate worked as an accountant for the Casa de Contratación, which managed trade with the Americas. He faced another accusation of financial mismanagement. The last known document about him is from 1585.

Zárate likely died after 1589, but the exact date is not known. He may have married a second time. A letter from his nephew mentions a daughter named Isabelica.

Works

Agustín de Zárate's only known work is his book, Historia del descubrimiento y conquista del Perú (History of the Discovery and Conquest of Peru). This book made him one of the most important Spanish historians of Peru. Other famous historians, like Francisco López de Gómara and Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, used Zárate's work as a source.

The Historia was very popular in the 1500s. It was published many times: in Spanish in 1555 and 1577, and translated into German, French, Italian (all in 1563), and English (1581).

Even though Zárate only stayed in Peru for about a year, he learned a lot about local life. He collected information and copied parts of other writings into his book. When he returned to Spain, he remembered the events in America. He wrote that he saw "so many rebellions and news in that land, that it seemed something worth of memory."

Zárate started writing his book while he was in prison after returning to Spain. The book has seven parts:

- The first four parts describe events from Francisco Pizarro's preparations for exploration up to Zárate's arrival in Peru.

- The last three parts describe what happened in Peru from 1544 to 1550. These parts are written with great detail and excitement, especially the fifth part, which Zárate witnessed himself.

Spanish historians and critics have highly praised Zárate's work. Many have called it a beautiful historical record and a work of great literary quality. They say he was a careful writer with a clear and graceful style.

In his Historia, Zárate often refers to the classical world of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. He sometimes compares the Inca Empire and the Spanish conquest to these ancient civilizations. He quotes famous classical writers like Horace, Seneca, Ovid, and Plato. He even uses Plato's myth of Atlantis to explain where the first people of America might have come from.

Even Pedro Cieza de León, another Spanish chronicler of Peru, said that Agustín de Zárate was considered "wise and well-read" in Latin.

Sources for the Historia

Zárate used several reports to write his book. He mainly used two:

- A manuscript from Viceroy Pedro de La Gasca that described Gonzalo Pizarro's rebellion.

- A report from Rodrigo Lozano, the mayor of Trujillo, which Zárate used for the early chapters about the discovery of Peru.

Zárate never said in his book how long he was a direct witness to events in Peru. Since he only stayed for about a year, he had to rely on other writings. He probably also used letters and reports from his nephew, Polo de Ondegardo, who stayed in Peru. It's unclear how Zárate learned so much about Inca religion for his first edition, given his short stay.

The 1577 New Edition

In 1577, a new Spanish edition of the book was printed with important changes. Zárate removed three chapters from the first part that discussed the Andean religion (which the Spanish called "idolatry"). He also rewrote parts of chapters 12 and 26 in the fifth part. He wanted to remove any hints about his past involvement in Gonzalo Pizarro's rebellion or his feelings about it. This new edition was printed in Seville.

The main reason for these changes was a shift in the Spanish government's attitude. When Zárate first showed his manuscript to Philip, Philip was a young prince. By 1563, Philip was king and had made the Spanish Inquisition much stronger. The government wanted to link God's cause with the Spanish monarchy's cause. Any negative comments about royal authority could be seen as an offense.

Censorship became much stricter between the first and later editions. A law in 1558 increased control over all printed materials. It even introduced the death penalty for those who kept or sold books banned by the Inquisition. New editions of already published books also had to follow these rules.

This led to a new official rule: the Christianization effort preferred to ignore the religious past of Native Americans rather than learn about it. This rule applied in Spain too. This is why Zárate removed the three chapters from his Historia that talked about pre-Hispanic Peruvian religion and myths.

Here's what those removed chapters were about:

- Chapter 10 described the creation legends of the Andean natives. It also mentioned their traditions about a great flood, which Zárate compared to the flood story in the Bible.

- Chapter 11 gave details about offerings and sacrifices to the huacas (Andean shrines), which the Spanish called idols. It included important information about human sacrifices in Peru. This chapter also reported that Andean natives compared the hats worn by Christian bishops to similar headwear on ancient statues. This made some Spanish people believe that these statues represented Christian apostles who might have preached in America long ago.

- Chapter 12 said that Andean natives believed in the resurrection of the body after death. Inca Garcilaso de la Vega thought this was a very important detail.

See also

In Spanish: Agustín de Zárate para niños

In Spanish: Agustín de Zárate para niños

- Pedro Cieza de León

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |