Ahmed ʻUrabi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ahmed ʻUrabi Pasha

|

|

|---|---|

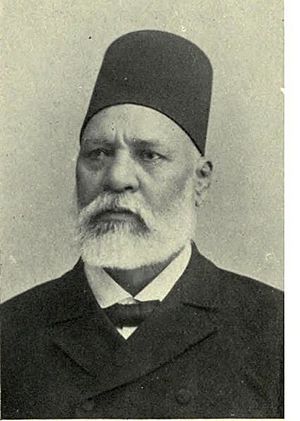

ʻUrabi in 1906

|

|

| Prime Minister of Egypt | |

| In office 1 July 1882 – 13 September 1882 |

|

| Monarch | Tewfik Pasha |

| Preceded by | Raghib Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Mohamed Sherif Pasha |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 31, 1841 Zagazig, Egypt |

| Died | September 21, 1911 (aged 70) Cairo, Egypt |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Battles/wars | Ethiopian–Egyptian War ʻUrabi revolt Anglo-Egyptian War |

Ahmed ʻUrabi (born March 31, 1841 – died September 21, 1911) was an important Egyptian leader. He was also known as Ahmed Ourabi or Orabi Pasha. He was a nationalist, meaning he strongly believed in his country, Egypt. He was also an officer in the Egyptian Army.

ʻUrabi was the first major political and military leader in Egypt to come from a peasant family, called fellahin. In 1879, he took part in a protest that grew into the ʻUrabi revolt. This revolt was against the ruler of Egypt, Khedive Tewfik. Tewfik's government was heavily influenced by Britain and France.

ʻUrabi became part of Tewfik's government. He started making changes to Egypt's army and government. However, protests in Alexandria in 1882 led to Britain attacking the city. This started the Anglo-Egyptian War. ʻUrabi and his supporters were captured. This led to Britain taking control of Egypt. ʻUrabi was sent away to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka).

Contents

Early Life and Army Career

Ahmed ʻUrabi was born in 1841. His village, Hirriyat Razna, was near Zagazig, about 80 kilometers north of Cairo. His father was a village leader and quite wealthy. This allowed ʻUrabi to get a good education.

He finished elementary school in his village. Then, in 1849, he went to Al-Azhar University to continue his studies. Later, he joined the army. He quickly rose through the ranks. By the age of 20, he was a lieutenant colonel.

ʻUrabi came from a peasant background. His modern education and military service were possible because of reforms by Khedive Ismail. Ismail wanted to modernize Egypt. He removed barriers between ordinary Egyptians and the ruling class. Before, only people of Balkan, Circassian, or Turkish origin could join the army. Ismail changed this. He allowed Egyptians and Sudanese from all backgrounds to join the military. These changes helped ʻUrabi rise in the army.

ʻUrabi served in the Ethiopian-Egyptian War from 1874 to 1876. He helped with supplies and communication lines. Egypt lost this war. ʻUrabi was very upset about how the war was managed. This experience made him interested in politics. It also turned him against the Khedive's rule.

Protesting for Change

ʻUrabi was a very powerful speaker. Because he came from a peasant family, many Egyptians saw him as a true voice for their people. His followers even called him 'El Wahid', meaning 'the Only One'.

Khedive Tewfik made a new law. This law stopped peasants from becoming army officers. ʻUrabi led a group protesting this law. They were against the special treatment given to aristocratic officers. ʻUrabi often spoke out against the unfair treatment of ethnic Egyptians in the army. He and his supporters, who included most of the army, succeeded. The unfair law was removed. In 1879, they formed the Egyptian Nationalist Party. They hoped to build a stronger Egyptian identity.

In February 1882, ʻUrabi and his army allies joined with reformers. They demanded big changes. This protest, known as the ʻUrabi revolt, aimed for fairness for Egyptians. They wanted everyone to be equal under the law. With support from peasants, ʻUrabi tried to free Egypt and Sudan from foreign control. He also wanted to end the Khedive's absolute rule. The Khedive himself was controlled by European influence. Egyptian leaders demanded a constitution. This would give power to a parliament. The revolt also showed anger against too much foreign influence. This included the Turkish and Circassian noble families.

Plans for a Parliament

ʻUrabi was first promoted to Bey, a high rank. Then he became an under-secretary of war. Finally, he became a member of the government. They started making plans for a new parliamentary assembly. During the last months of the revolt in 1882, ʻUrabi was said to be the Prime Minister. This was for a new government based on what the people wanted.

Khedive Tewfik felt threatened by ʻUrabi. He asked the Ottoman Sultan for help. Egypt and Sudan were still technically loyal to the Sultan. But the Sultan was slow to respond.

British Involvement

Britain was worried that ʻUrabi might not pay Egypt's huge debts. They also feared he might take control of the Suez Canal. So, Britain and France sent warships to Egypt. They wanted to stop any problems. Tewfik fled to the ships for protection. He moved his court to Alexandria.

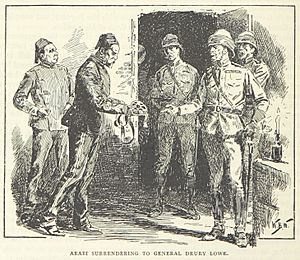

The strong presence of warships made people fear an invasion. This led to anti-Christian riots in Alexandria on June 12, 1882. The French fleet left, but the Royal Navy ships stayed. They fired on the city's artillery after Egyptians ignored a warning. In September, a British army landed in Alexandria. They were stopped at the Battle of Kafr El Dawwar. Another British army, led by Sir Garnet Wolseley, landed near the Suez Canal. On September 13, 1882, they defeated ʻUrabi's army at the Battle of Tell El Kebir. After this, the British marched to Cairo. Cairo surrendered without a fight. ʻUrabi and other nationalist leaders were captured.

Exile and Return

ʻUrabi was put on trial for rebellion on December 3, 1882. He was found guilty and sentenced to death. However, the sentence was immediately changed. He was sent away for life instead. He left Egypt on December 28, 1882. He went to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka).

His home in Kandy, Ceylon, is now the Orabi Pasha Cultural Center. While in Ceylon, ʻUrabi worked to improve education for Muslims there. He helped establish Hameed Al Husseinie College in 1884. This was Sri Lanka's first school for Muslims. He also supported the founding of Zahira College in 1892.

In May 1901, Khedive Abbas II allowed ʻUrabi to return to Egypt. Abbas was Tewfik's son and the new ruler. He was a nationalist, like his grandfather Ismail. Abbas was also against British influence in Egypt. ʻUrabi returned on October 1, 1901. He stayed in Egypt until he died on September 21, 1911.

Legacy

The British said their intervention in Egypt was only temporary. But British forces stayed in Egypt for many decades. In 1914, during World War I, Britain removed Khedive Abbas II. They feared he might side with the Ottoman Empire. Egypt then became a sultanate and a British protectorate. Britain recognized Egyptian independence in 1922. This happened after a revolution in 1919.

ʻUrabi's revolt was very important for Egypt. It was the first time strong nationalist feelings appeared in Egypt. These feelings later played a big role in Egyptian history. Some historians say the 1881–1882 revolution also laid the groundwork for modern politics in Egypt. In the 20th century, especially under Gamal Abdel Nasser, ʻUrabi was seen as a national hero. He also inspired political activists in Ceylon.

Places Named After ʻUrabi

- Arabi, Louisiana: A suburb in the United States named after him. Its residents felt connected to his fight for independence.

- A main street and an underground station in Cairo's Al Mohandessin district bear his name.

- Orabi Square in Alexandria honors him.

- The main square in Zagazig has a statue of ʻUrabi on a horse. Its university's emblem also features his picture.

- A coastal road in the Gaza Strip is named Ahmed Orabi Street.

- Orabi Pasha Street in Central Colombo, Sri Lanka, is named after him.

- The Orabi Pasha Cultural Center in Kandy preserves his former house.

See also

In Spanish: Ahmed Orabi para niños

In Spanish: Ahmed Orabi para niños