Army of the Rhine and Moselle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Army of the Rhine and Moselle |

|

|---|---|

Fusilier of a French Revolutionary Army

|

|

| Active | 20 April 1795 – 29 September 1797 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | First Republic |

| Disbanded | 29 September 1797 and units merged into Army of Germany |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Jean-Charles Pichegru Jean Victor Marie Moreau Louis Desaix Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr |

The Army of the Rhine and Moselle (French: Armée de Rhin-et-Moselle) was an important military group of the French Revolutionary Army. It was created on April 20, 1795. This army was formed by combining parts of the Army of the Rhine and the Army of the Moselle.

This army fought in two main campaigns during the War of the First Coalition. French military leaders in Paris created armies for specific jobs. The job of this army was to protect the French border along the Rhine river. It also aimed to move into the German states and possibly threaten Vienna, the capital of Austria.

The 1795 campaign was not successful. General Jean-Charles Pichegru was removed from command after it. In 1796, under General Jean Victor Marie Moreau, the army did much better. They defeated enemy forces at Kehl and moved into southwestern Germany.

The success of this army depended on working with France's Army of the Sambre and Meuse. This other army was led by Jean-Baptiste Jourdan. In 1796, rivalries between Jourdan and Moreau, and even among their officers, made it hard for both armies to work well together.

After a summer of fighting, the Coalition forces led the French deeper into German lands. The Austrian commander, Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen, defeated the French at Wurzburg and second Wetzlar. He then beat Jourdan's army at the Limburg-Altenkirchen. These defeats meant Jourdan's army and Moreau's Army of the Rhine and Moselle could not join forces.

Once Jourdan went back to the west side of the Rhine, Charles focused on Moreau. By October, they were fighting in the Black Forest. By December, Charles had surrounded the French forces at the main river crossings of Kehl and Hüningen. By early 1797, the French had lost control of these river crossings. After a short campaign in 1797, France and Austria signed the Treaty of Campo Formio. On September 29, 1797, the Army of the Rhine and Moselle joined with the Army of the Sambre and Meuse. They formed the Army of Germany.

The campaigns of the Army of the Rhine and Moselle helped train many young officers. A historian named Ramsey Weston Phipps called it a "school for marshals." This means it was a great place for future leaders of Napoleon's army to gain experience.

Contents

Why Was the Army Formed?

The French Revolution and European Reactions

In 1789, the French Revolution began. At first, other European rulers saw it as a problem only for the French king. But by 1791, Leopold II, the Holy Roman Emperor, worried about his sister, Marie Antoinette, who was the French queen.

In August 1791, Leopold and Frederick William II of Prussia issued the Declaration of Pillnitz. They said that the safety of European kings was linked to the safety of the French royal family. They threatened action if anything happened to the king and queen. French nobles who had left France, called émigrés, kept asking for help to stop the revolution.

On April 20, 1792, the French National Convention declared war on Austria. This started the War of the First Coalition (1792–1798). In this war, France fought against most of the countries bordering it, plus Portugal and the Ottoman Empire.

Early Battles and the Rhine River

Parts of the armies that later formed the Army of the Rhine and Moselle fought in the capture of the Netherlands. They also took part in the siege of Luxembourg. These armies won a big victory at the Battle of Fleurus on June 16, 1794.

After Fleurus, the enemy forces in Flanders collapsed. The French armies took over the Austrian Netherlands and the Dutch Republic in the winter of 1794–1795. From then on, the Rhine river became a key defense line. Controlling its crossings was vital for both sides.

Challenges for the French Army

By 1792, the armies of the French Republic were in a messy state. Experienced soldiers from the old royal army fought alongside new volunteers. These new recruits were full of revolutionary spirit. But they often lacked discipline and training. They sometimes refused orders and caused problems within their units. After a defeat, they might even mutiny.

Things got harder in 1793 with the "levée en masse" (mass conscription). This meant many ordinary people were forced to join the army. The basic army unit, the demi-brigade, mixed old soldiers with new recruits. Ideally, it combined well-trained old soldiers with less trained National Guard units and poorly trained volunteers.

Leadership was also a problem. French commanders had to balance protecting the border with the demands for victory from Paris. Commanders were often suspected of disloyalty. If they failed, they could face the guillotine. Many top generals were executed. Many old officers had left France to join enemy armies. The cavalry, in particular, suffered from this. However, the artillery, which was less popular with the old nobility, remained strong.

By 1794-95, French military planners saw the upper Rhine Valley and the Danube river basin as very important. The Rhine was a strong barrier against Austrian attacks. Controlling its crossings meant controlling access to lands on both sides. Access across the Rhine and through the Black Forest led to the upper Danube valley. For the French, controlling this area was key to reaching Vienna.

The French also wanted to move their army out of France. Their army needed to live off the land it occupied. The French government believed war should pay for itself. They did not set aside money to pay or feed their soldiers. This helped with some problems, but not all. Soldiers were paid in a worthless paper money called the Assignat until April 1796. After that, they got metal coins, but pay was still often late. Soldiers often mutinied because of this.

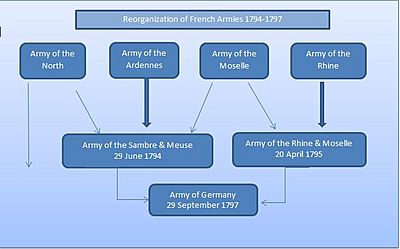

How the Army Was Formed

In late 1794, military planners in Paris reorganized the army. The right side of the Armies of the Center (later the Army of the Moselle), the entire Army of the North, and the Army of the Ardennes were combined. They formed the Army of the Sambre and Meuse. This army was placed on the west bank of the Rhine, north of where the Main and Rhine rivers meet.

The remaining parts of the old Army of the Center and the Army of the Rhine were united. This happened on November 29, 1794, and officially on April 20, 1795. Jean-Charles Pichegru was put in command. These troops were stationed further south. Their line stretched on the west bank of the Rhine from Basel to the Main River.

At Basel, the Rhine river turns north. It enters a wide valley called the Rhine Ditch. This valley is about 31 kilometers (19 miles) wide. It is bordered by the Black Forest mountains on the German side and the Vosges mountains on the French side. Further north, the river became deeper and faster. It then widened into a delta before flowing into the North Sea.

The 1795 Campaign

The Rhine Campaign of 1795 (April 1795 to January 1796) started with both French armies trying to cross the Rhine. Their goal was to capture the Fortress of Mainz. The French Army of the Sambre and Meuse, led by Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, faced Count Clerfayt's army in the north. The French Army of Rhine and Moselle, under Pichegru, faced Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser's army in the south.

From April to August, both sides waited. Then, in August, Jourdan crossed the river and quickly took Düsseldorf. The Army of the Sambre and Meuse moved south to the Main River, completely cutting off Mainz. Pichegru's Army of the Rhine and Moselle surprised the Bavarian soldiers at Mannheim. By mid-August, both French armies had strong positions on the east bank of the Rhine.

However, the French wasted their good start. Pichegru missed a chance to capture Clerfayt's supply base at the Battle of Handschuhsheim, losing many soldiers. With Pichegru not acting, Clerfayt focused on Jourdan. He defeated Jourdan at Höchst in October. This forced most of the Army of the Sambre and Meuse to retreat to the west bank of the Rhine.

These events left the Army of the Rhine and Moselle alone. When Wurmser blocked the French crossing at Mannheim, the Army of the Rhine and Moselle was trapped on the east bank. The Austrians defeated the left side of the Army of Rhine and Moselle at the Battle of Mainz. They then moved down the west bank. In November, Clerfayt defeated Pichegru at Pfeddersheim. He successfully completed the siege of Mannheim. In January 1796, Clerfayt made a truce with the French. This sent the Army of the Rhine and Moselle back to France. The Austrians kept large parts of the west bank.

The 1796 Campaign

The 1796 Rhine Campaign began with Jean-Baptiste Kléber's attack south of his crossing point at Düsseldorf. After Kléber gained enough space on the east bank of the Rhine River, Jean Baptiste Jourdan was supposed to join him. This would be with the rest of the Army of the Sambre and Meuse.

At the first battles of Altenkirchen (June 4, 1796) and Wetzlar, two French divisions attacked a part of the Austrian army. A direct attack combined with a move around the enemy's side forced the Austrians to retreat. Three future Marshals of France played important roles at Altenkirchen. These were François Joseph Lefebvre, Jean-de-Dieu Soult, and Michel Ney. Altenkirchen is about 50 kilometers (31 miles) east of Bonn. Wetzlar was about 66 kilometers (41 miles) north of Frankfurt.

Altenkirchen was a trick to make the Austrian commander move troops from the south. Moreau made this trick seem real by moving part of the Army of the Rhine and Moselle north from Strasburg. When Archduke Charles moved troops north to stop what looked like a big crossing, Moreau quickly turned back to Kehl and crossed the river. Kléber did his part of the plan perfectly.

The enemy armies of the First Coalition included troops from the Holy Roman Empire. They also had infantry and cavalry from various states. This force totaled about 125,000 soldiers. This was a large army for the 1700s. Habsburg troops made up most of the army. But they could not cover the area from Basel to Frankfurt well enough. In spring 1796, new soldiers from cities and states joined the Habsburg force. This added about 20,000 men.

Archduke Charles, who commanded the enemy forces, did not like using these new militias. They were poorly trained. Charles had only half the number of French troops. His forces stretched over a 211-mile front, from Basel to Bingen. Charles had put most of his army between Karlsruhe and Darmstadt. This area was likely to be attacked because it offered a way into eastern German states and to Vienna.

On June 22, Moreau's Army of the Rhine and Moselle crossed the river at Kehl and Hüningen at the same time. At Kehl, Moreau's advance group of 10,000 men moved first. The main force of 27,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry followed. They faced only a few hundred Swabian guards on the bridge. The Swabians were greatly outnumbered and could not get help. Most of the Imperial Army was further north. So, within a day, Moreau had four divisions across the river.

The Swabian soldiers were forced out of Kehl. They regrouped at Rastatt by July 5. Neither Louis Joseph, Prince of Condé's army in Freiburg nor Karl Aloys zu Fürstenberg's force in Rastatt could reach Kehl in time. Also, at Hüningen, near Basel, Ferino made a full crossing. He moved east along the German side of the Rhine with several units. The Austrian and Imperial armies were in danger of being surrounded.

With Ferino's quick moves, Charles made an organized retreat. He moved his four columns through the Black Forest and toward Bavaria. By mid-July, the French kept pushing Charles's army. Two enemy columns near Stuttgart were surrounded and surrendered. This led to a truce with the Swabian Circle. The third column, including Condé's Corps, retreated through Waldsee to Stockach, and then to Ravensburg. The fourth Austrian column, the smallest, marched along the northern shore of Lake Constance.

Because of the size of the attacking French force, Charles had to retreat deep into Bavaria. This was to line up his northern flank with Wartensleben's army. As he retreated, his own line became stronger. The French lines, however, stretched out and became weaker. During this retreat, most of the Swabian Circle was left to the Army of the Rhine and Moselle. This army forced a truce and took large payments. The French also occupied several towns in southwestern Germany. These included Stockach, Constance, Ulm, and Augsburg. As Charles retreated further east, a neutral zone grew. It eventually covered most of southern German states.

Summer of 1796: The Tide Turns

By mid-summer, the Army of the Rhine and Moselle seemed to be succeeding. Jourdan and Moreau looked like they were about to surround Charles and Wartensleben. They hoped to split the two enemy armies. But Wartensleben kept retreating east-north-east, even though Charles ordered him to join forces.

At the Battle of Neresheim on August 11, Moreau defeated Charles's army. Finally, Wartensleben realized the danger. He changed direction, moving his troops to join Charles's northern side. At the Battle of Amberg on August 24, Charles defeated the French again. But on the same day, his commanders lost a battle to the French at Friedberg. There, the French army isolated an Austrian infantry unit.

The war then turned in favor of the Coalition. Both French armies had stretched their lines too far into Germany. They were too far apart to help each other. The Coalition's forces pushed a wider gap between Jourdan's and Moreau's armies. This was what the French had tried to do to Charles and Wartensleben.

Even though Charles told him to retreat north, Maximilian Anton Karl, Count Baillet de Latour retreated east. He wanted to protect Austria's borders. Moreau did not take the chance to place his army between the two Austrian forces. As the French retreated toward the Rhine, Charles and Wartensleben pushed forward. On September 3 at Würzburg, Jourdan tried to stop the retreat but failed. At the Battle of Limburg, Charles pushed him back to the Rhine.

Once Moreau heard about Jourdan's defeat, he began his retreat from southern Germany. He retreated through the Black Forest. Ferino oversaw the rear guard. Moreau claimed one more victory: an Austrian group came too close to Moreau at Biberach. They lost 4,000 prisoners, flags, and cannons.

Both sides faced heavy rains. The ground was soft and slippery. The Rhine and Elz rivers had flooded. This made cavalry attacks harder. Archduke Charles's forces chased the French carefully. The French tried to slow them down by destroying bridges. But the Austrians repaired them and crossed the swollen rivers.

Near Emmendingen, the Archduke split his force into four groups. They attacked the French. The French retreated across the rivers, destroying all bridges.

After the chaos at Emmendingen, the French retreated south and west. They prepared for battle near Schliengen. Moreau placed his army along a ridge of hills. This gave them a strong position. Because of the bad roads in late October, Archduke Charles could not go around the French right side. The French left side was too close to the Rhine. The French center was too strong to attack directly. Instead, Charles attacked the French sides head-on. This caused many casualties for both sides.

The Duc d'Enghien led a brave attack on the French left. This cut off their way to retreat through Kehl. Nauendorf's group marched all night and half the day. They attacked the French right, pushing them back further. During the night, while Charles planned his next attack, Moreau began moving his troops toward Hüningen.

Although both the French and Austrians claimed victory, historians agree the Austrians gained a strategic advantage. However, the French left the battlefield in good order. Several days later, they crossed the Rhine River at Hüningen.

Sieges at Kehl and Hüningen

After Schliengen, both the French and the Coalition wanted to control the Rhine river crossings at Kehl and Hüningen. At Kehl, 20,000 French defenders under Louis Desaix and Jean Victor Marie Moreau almost won the siege. They made a surprise attack that nearly captured the Austrian cannons. The French managed to capture 1,000 Austrian soldiers.

On January 9, General Desaix suggested leaving Kehl to General Latour. They agreed that the Austrians would enter Kehl the next day, January 10, at 4:00 PM. The French quickly repaired the bridge. This gave them 24 hours to take everything valuable and destroy everything else. By the time Latour took the fortress, nothing useful was left. The French made sure the Austrians could not use anything. Even the fortress itself was just dirt and ruins. The siege ended after 115 days.

At Hüningen, Karl Aloys zu Fürstenberg's forces started the siege soon after the Austrian victory at Schliengen. Most of this siege happened at the same time as the siege at Kehl. Troops from Kehl marched to Hüningen to prepare for a big attack. But the French defenders surrendered on February 1, 1797. The French commander, Jean Charles Abbatucci, was killed early in the fighting. Georges Joseph Dufour replaced him.

The trenches, first dug in November, had filled with winter rain and snow. Fürstenberg ordered them opened again, and the water drained on January 25. The Coalition forces secured the earthworks around the trenches. On January 31, the French failed to push the Austrians out. Archduke Charles arrived that day.

The night of January 31 to February 1 was calm, with only regular artillery fire. At midday on February 1, 1797, as the Austrians prepared to storm the bridgehead, General Dufour offered to surrender. This avoided a costly attack for both sides. On February 5, Fürstenberg finally took control of the bridgehead.

After the losses in 1796 and early 1797, the French gathered their forces on the west side of the Rhine. A short campaign in late spring of 1797 led to a peace agreement between Austria and France. This was the Treaty of Campo Formio, which ended the War of the First Coalition. The later truce at Leoben led to long talks for peace. On September 29, 1797, the Army of the Rhine and Moselle joined with the Army of the Sambre and Meuse. They formed the Army of Germany.

Challenges for Commanders

The Army of the Rhine and Moselle faced many leadership problems early on. The 1795 campaign was a complete French failure. The difficulties came partly from Pichegru's own situation. He competed with both Moreau and Jourdan. He also disagreed with the direction the revolution was taking.

Pichegru was replaced by Desaix, and later Moreau. Pichegru was a skilled and popular commander. But his actions sometimes seemed strange. He captured Mannheim but then allowed Jourdan to be defeated. Throughout 1796, his actions in Paris made it harder to run military operations in Germany.

In 1796, competition between generals caused problems, not just political ideas. Jourdan and Moreau were jealous of each other. They refused to combine their armies. Moreau moved quickly into Bavaria, as if he was the only French army in Germany. This frustration led to rivalries among lower-ranking commanders too. Ferino kept making seemingly random moves near the Swiss border. He acted as if he was in charge of his own army.

These problems were not only in Moreau's army. In the Army of the Sambre and Meuse, Jourdan argued with his wing commander Kléber. Kléber suddenly resigned. Two generals close to Kléber also found reasons to leave. Faced with this, Jourdan replaced them.

A School for Future Leaders

The campaigns of the Army of the Rhine and Moselle gave great experience to many talented young officers. Historian Ramsey Weston Phipps wrote about how important this experience was. Officers learned to lead in tough conditions. There were not enough soldiers, training was poor, and supplies were short. There was also confusion in battle plans.

Phipps's idea was that the training officers received depended on where they served and which army they belonged to. Young officers learned a lot from experienced leaders like Pichegru, Moreau, Lazar Hoche, Lefebvre, and Jourdan.

Phipps's idea is not unique. In 1895, Richard Phillipson Dunn-Pattison also called the French Revolutionary army "the finest school the world has yet seen for an apprenticeship in the trade of arms." Later, Emperor Napoleon I brought back the title of Marshal. This helped him reward his best generals and soldiers from the French Revolutionary Wars.

The Army of the Rhine and Moselle included five future Marshals of France: Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, Jean-Baptiste Drouet, Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr, and Édouard Adolphe Casimir Joseph Mortier. François Joseph Lefebvre, though older by 1804, was named an honorary marshal. Michel Ney, a brave cavalry commander in 1795–1799, learned to command under Moreau and Massena. Jean de Dieu Soult served under Moreau and Massena. Jean Baptiste Bessieres, like Ney, was a good regimental commander in 1796. MacDonald, Oudinot, and Saint-Cyr, who fought in the 1796 campaign, all received honors later.

Commanders of the Army

See Also

Images for kids