Asian immigration to the United States facts for kids

Asian immigration to the United States is about people moving to the United States from different parts of Asia. This includes places like East Asia, Southeast Asia, and South Asia. People from Asia have been in the land that is now the U.S. since the 1500s.

The first big wave of Asian immigrants came in the late 1800s. They mostly settled in Hawaii and on the West Coast. For many years, from 1875 to 1965, U.S. laws made it very hard for Asians to immigrate. They were also mostly not allowed to become U.S. citizens until the 1940s. After 1965, when new immigration laws were passed, many more people from Asia began to move to the United States.

Contents

History of Asian Immigration

Early Arrivals (before 1830s)

The first people from Asia known to arrive in North America after Europeans came were Filipinos. They were part of a Spanish ship's crew that landed in Morro Bay, California, in 1587. This was part of a trade route between the Philippines and Spain's colonies in North America.

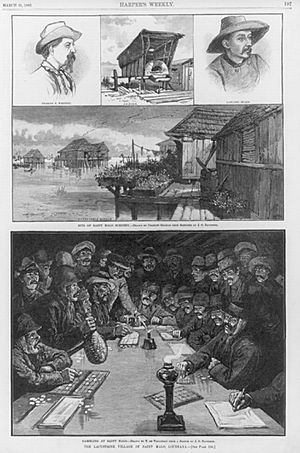

More Filipino sailors came to California as both places were part of the Spanish Empire. By 1763, Filipino "Manila men" had a settlement called St. Malo near New Orleans, Louisiana. A few Chinese merchants also lived in the U.S. by 1815.

First Big Wave (1850–1917)

By the 1830s, people from East Asia started moving to Hawaii. American business owners had set up large farms there. These early immigrants, mostly from China, Japan, Korea, India, and the Philippines, came to work on these farms. They were often hired under special contracts.

When Hawaii became part of the United States in 1893, many Asians were already living there. More continued to arrive. Plantation owners in Hawaii brought in Chinese workers for cheap labor starting in 1852. They also brought in workers from other Asian countries to keep wages low.

- Between 1885 and 1924, about 30,000 Japanese came to Hawaii as government-sponsored workers.

- Another 170,000 Japanese immigrants came to Hawaii between 1894 and 1924.

- Thousands of Koreans moved to Hawaii in the early 1900s, escaping hardship in Korea.

- Filipinos, who were U.S. colonial subjects after 1898, also came to Hawaii by the "tens of thousands" in the early 1900s.

Gold Rush and Railroads

The first major wave of Asian immigration to the mainland U.S. happened on the West Coast. This started during the California Gold Rush in the 1850s. The number of Chinese immigrants in California grew from under 400 in 1848 to 25,000 by 1852. Most Chinese immigrants came from the Guangdong province. They hoped to find opportunities and send money back to their families.

Asian immigrants were needed across the U.S. for cheap labor in mines, factories, and on the Transcontinental Railroad. Some farm owners in the South also wanted Chinese workers to replace enslaved labor. Chinese workers often borrowed money from brokers to travel. They would pay it back with their wages after arriving. Many Chinese merchants also came, opening businesses that became the first Chinatowns.

Japanese, Korean, and South Asian immigrants also arrived in the mainland U.S. from the late 1800s. They also came to fill the need for workers. Japanese immigrants, many of whom were farmers, started coming in large numbers in the 1890s after Chinese immigration was restricted. By 1924, 180,000 Japanese immigrants had come to the mainland.

Filipino migration to North America continued, with reports of "Manila men" in California gold camps in the 1840s. By 1880, the census showed 105,465 Chinese and 145 Japanese immigrants. This shows that Chinese immigrants were the main Asian group on the mainland at that time.

Growing Hostility and Exclusion Laws

In the 1860s and 1870s, people in the U.S. became more hostile towards Asian workers. Groups like the Asiatic Exclusion League formed. East Asian immigrants, especially Chinese Americans, faced discrimination and violence. They were often seen as a "yellow peril". Attacks and even lynchings of Chinese people were common. The Rock Springs massacre was a terrible event where white miners killed nearly 30 Chinese immigrants. They accused the Chinese of taking their jobs.

In 1875, Congress passed the Page Act. This was the first law to restrict immigration. It said that forced laborers from Asia and Asian women were "undesirable" and could not enter the U.S. In reality, this law mostly stopped Chinese women from coming to the U.S. This prevented male workers from bringing their families.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 stopped almost all immigration from China. This was the first U.S. immigration law to ban people based on their race or country of origin. Only a few merchants, diplomats, and students were allowed. The law also stopped Chinese immigrants from becoming U.S. citizens. The Geary Act of 1892 made Chinese people carry special certificates to prove they had the right to be in the U.S.

Even with these harsh laws, Chinese immigrants fought for their rights. They continued to seek voting rights and citizenship. In 1898, the Supreme Court case United States v. Wong Kim Ark ruled that a person born in the U.S. to Chinese immigrant parents was a U.S. citizen at birth. This was a very important decision for birthright citizenship.

New Groups and More Restrictions

After Chinese immigration was restricted, Japanese and South Asian workers filled the labor demand. By 1900, there were 24,326 Japanese residents in the U.S. The first South Asian immigrants, mostly Punjabi Sikh farmers, arrived in 1907. About 6,400 South Asians came to America during this time. Like Chinese and Japanese immigrants, most were men. Some Bengali Muslim craftsmen and merchants also came to the East Coast.

Anti-Asian hostility continued. There were riots in 1907 in places like San Francisco, California, and Bellingham, Washington. In Bellingham, a mob attacked hundreds of South Asian immigrants. The U.S. then made the 1907 Gentleman's Agreement with Japan. Japan agreed to stop its citizens from moving to the U.S. In return, the U.S. agreed to fewer restrictions on Japanese immigrants. This meant Japanese immigrants were mostly banned unless they already owned property or were immediate family members. Many Japanese women came as "picture brides" to marry men already in the U.S. Korean women also came this way, as Korea was under Japanese rule.

After the Spanish–American War in 1898, the U.S. took control of the Philippines. Filipinos became U.S. nationals, so they were not initially affected by exclusion laws. Many Filipinos came as farm workers. The U.S. government also helped some Filipino students, called pensionados, to study in U.S. colleges. However, in 1934, the Tydings–McDuffie Act promised independence to the Philippines. It also sharply limited Filipino immigration to only 50 people per year.

Exclusion Era (1917–1943)

The laws against Chinese and Japanese immigration were made even stronger. The Asiatic Barred Zone Act of 1917 banned all immigration from a large area of Asia. This included parts of the Middle East, Central Asia, the Indian Subcontinent, and Southeast Asia.

The Immigration Act of 1924 set limits on immigration from all countries. It also banned immigrants who were "ineligible for citizenship." This meant almost no Asian immigration to the U.S. The act also created the United States Border Patrol. There were a few exceptions. Filipinos could still immigrate until 1934 because they were U.S. nationals. Also, Asian immigrants could still go to Hawaii, which was a U.S. territory.

After these exclusion laws, Chinese immigrants faced more challenges. They moved away from farm work and railroad jobs. Many started their own businesses like laundries, stores, and restaurants. They often gathered in Chinatowns across the country.

The South Asian population had a very uneven number of men and women. Many Punjabi Sikh men in California married women of Mexican descent. This helped them avoid laws and prejudice that stopped them from marrying white people.

Citizenship Rulings

Two important Supreme Court cases during this time decided who could be a U.S. citizen.

- In 1922, Takao Ozawa v. United States ruled that Japanese people were not "Caucasian." So, they could not become citizens under the law that only allowed "free white persons" to naturalize.

- A few months later in 1923, United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind ruled that even though Indians were sometimes considered "Caucasian" by scientists, they were not seen as "white" by most people. So, they also could not become citizens.

These cases confirmed that foreign-born Asian immigrants were legally stopped from becoming citizens because of their race. Even though children born in the U.S. to Asian parents were citizens, first-generation immigrants could not become citizens.

Asian immigrants continued to face discrimination. Second-generation Asian Americans, who were citizens, still faced segregation in schools and problems finding jobs. They were also often not allowed to own property or businesses.

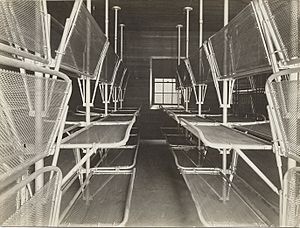

The worst discrimination against Asian Americans happened during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, about 110,000 to 120,000 Japanese Americans on the West Coast were forced into internment camps. Most of these people were U.S. citizens by birth.

Ending Exclusion (1943–1965)

After World War II, U.S. immigration laws began to change.

- In 1943, the Magnuson Act ended 62 years of Chinese exclusion. It allowed 105 Chinese people to immigrate each year. It also let Chinese people already in the U.S. become citizens.

- In 1946, the Luce–Celler Act allowed Filipinos and Indians to become citizens. It set a quota of 100 immigrants per year from each country.

These changes led to the McCarran–Walter Act in 1952. This law removed the "free white persons" rule. This meant Asian and other non-white immigrants could finally become citizens. However, it still kept strict limits on immigration from Asia. One important exception was for family members of U.S. citizens, including "war brides" who married American soldiers.

New Waves of Asian Immigration (1965–present)

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 changed everything. It removed the old rules that blocked most Asian immigrants. Instead, it set the same immigration limits for every country. This led to a huge increase in Asian immigration.

- In 2021, 31% of all immigrants in America were born in Asia.

- By 2019, there were 29 times more Asian immigrants than in 1960.

Asian Americans are a very diverse group. Different groups came for different reasons. For example, over 50% of Vietnamese immigrants in the 1900s came because of war or political problems. In contrast, only 5% of Filipino immigrants and 16% of Chinese immigrants came for those reasons. Filipino and Chinese immigrants were also more likely to have a higher education than Vietnamese immigrants.

Senator Hiram Fong from Hawaii spoke about these changes in 1965. He believed that Asian immigrants would not change America's culture much because they were a small part of the population.

U.S. wars also affected Asian immigration. After World War II, laws favored family reunification. This helped bring skilled workers to the U.S. The Luce–Celler Act of 1946 also helped immigrants from India and the Philippines.

The end of the Korean War and Vietnam War brought new waves of immigrants from Korea, Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. Some were war brides who later brought their families. Others were highly skilled or refugees seeking safety. More recently, groups like South Asians and mainland Chinese have grown. This is due to larger families, more family reunification visas, and more skilled workers coming on special work visas.

Modern Chinese Immigration

Since 1965, Chinese immigration has been helped by the U.S. having separate immigration limits for Mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. In the 1960s and 1970s, most Chinese immigrants came from Taiwan. A smaller number came from Hong Kong as students. Immigration from Mainland China was very low until 1977. Then, China allowed more people to leave, leading to more students and professionals coming to the U.S. These new Chinese immigrants often settled in suburban areas instead of older Chinatowns.

One famous suburban Chinatown is Monterey Park, California. In the 1970s, it was mostly a white middle-class area. But a Chinese real estate agent, Frederic Hsieh, invested in properties there. He marketed it to wealthy Chinese in Taiwan and Hong Kong as a "Chinese Beverly Hills." Many wealthy Chinese were interested in investing due to political issues in Asia.

Changing Demographics

The changes in immigration laws have greatly shifted the Asian American population. Japanese Americans were once the largest Asian American group. In 1970, there were nearly 600,000 Japanese Americans. But today, due to lower birth rates and less immigration, they are the sixth-largest Asian American group. Japanese Americans have high rates of being born in the U.S. and becoming citizens.

Before 1990, there were fewer South Asians than Japanese Americans. By 2000, Indian Americans almost doubled in population. They became the third-largest Asian American group. They are very visible in tech areas like Silicon Valley. Indian Americans have some of the highest rates of academic success in the U.S. Most speak English and are highly educated.

Today, Chinese, Indians, and Filipinos are the three largest Asian ethnic groups immigrating to the United States. Asians in the U.S. are a very diverse group and are growing fast. Asian Americans make up 6% of the U.S. population and are expected to reach 10% by 2050.

Timeline of Key Laws and Rulings

- 1875 Page Act: This law was the first to restrict immigration. It stopped forced laborers from Asia and Asian women from entering the U.S.

- 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act: This law banned almost all immigration from China. It also made it very hard for Chinese Americans to move around.

- 1898 United States v. Wong Kim Ark: The Supreme Court ruled that a U.S.-born son of Chinese immigrants was a U.S. citizen. This was based on the birthright citizenship part of the 14th Amendment.

- 1917 Asiatic Barred Zone Act: This law banned immigration to the U.S. from most of Asia. This included the Indian Subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and parts of the Middle East.

- 1922 Ozawa v. United States: The Supreme Court ruled that Japanese people could not become citizens. This was because they were not considered "white" or Caucasian at the time.

- 1923 United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind: The Supreme Court ruled that Indians could not become citizens. Even though some scientists called them "Caucasian," they were not seen as "white" by most people.

- 1924 Immigration Act of 1924: This law set immigration limits based on country of origin. It set a zero limit for Asian countries. It also created the United States Border Patrol.

- 1943 Magnuson Act: This law ended the ban on Chinese immigration. It allowed a small number of Chinese people to immigrate each year. It also let Chinese people already in the U.S. become citizens.

- 1945 War Brides Act: This law temporarily lifted the ban on Asian immigration for the spouses and adopted children of U.S. service members.

- 1946 Luce–Celler Act: This law allowed Indian Americans and Filipino Americans to become citizens. It allowed 100 immigrants per year from India and 100 from the Philippines.

- 1952 Walter–McCarran Act: This law removed all federal anti-Asian exclusion laws. It allowed all Asians to become citizens. However, strict immigration limits still remained.

- 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments of 1965: This important law removed all racial and nationality-based discrimination in immigration limits.

- 1989 American Homecoming Act: This law allowed children of American soldiers and Vietnamese mothers (called Amerasian children) to immigrate to the United States.

Images for kids

See Also

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |