Yellow Peril facts for kids

The Yellow Peril (also known as the Yellow Terror) was a racist idea that showed people from East Asia and Southeast Asia as a big danger to the Western world. This idea used a "color-metaphor" to describe them.

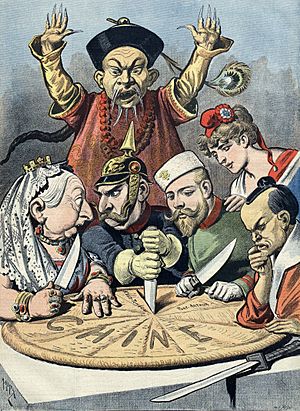

This racist belief came from ideas in the 1800s that pictured East Asians as less developed or even dangerous. During this time, Western countries were expanding their power. In the late 1800s, a Russian thinker named Jacques Novikow used the term "Le Péril Jaune" (The Yellow Peril). Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany later used this idea to encourage European countries to take over parts of China. He also used it to make the Japanese and Asian victory over Russia in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) seem like a threat to white Europe. He even suggested that China and Japan were working together to take over the Western world.

Contents

What is the Yellow Peril?

The racist ideas and cultural stereotypes of the Yellow Peril started in the late 1800s. This was when Chinese workers legally moved to countries like Australia, Canada, the U.S., and New Zealand. Their hard work sometimes caused a racist reaction because they would work for lower wages than local white people.

In 1870, a French historian named Ernest Renan warned Europeans about a danger from the East. However, he was actually talking about the Russian Empire, which some in the West saw as more Asian than European.

Germany's Role

From 1870, the Yellow Peril idea gave a clear shape to anti-East Asian racism in Europe and North America. In central Europe, a diplomat named Max von Brandt told Kaiser Wilhelm II that Germany had plans for colonies in China. Because of this, the Kaiser used the phrase die Gelbe Gefahr (The Yellow Peril). He used it to support Germany's interests and to justify European countries taking over land in China.

In 1895, Germany, France, and Russia worked together in the Triple Intervention. They forced Imperial Japan to give up its Chinese colonies after the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895). This event helped lead to the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05). The Kaiser said this was needed to protect white Western Europe from a made-up danger from the "yellow race."

To justify European control, the Kaiser used a picture called Peoples of Europe, Guard Your Most Sacred Possessions (1895) by Hermann Knackfuss. This picture showed Germany leading Europe, with warriors fighting a "yellow peril" from the East. This "peril" was shown as a dark cloud with a calm Buddha surrounded by flames. The Kaiser believed this picture showed a coming "race war" that would decide who ruled the world in the 1900s.

Russia's Fears

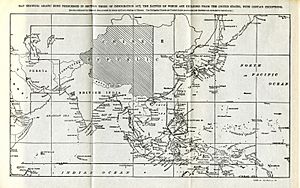

In the late 1800s, after a treaty, China got back some land that Russia had taken. At this time, Western news often made China seem like a rising military power. They used the Yellow Peril idea to create fears that China would conquer Western colonies, like Australia.

Russian writers also worried about a "second Tatar yoke" or a "Mongolian wave." Vladimir Solovyov, a philosopher, combined Japan and China into "Pan-Mongolians" who he thought would conquer Russia and Europe. Other writers like Dmitry Merezhkovskii shared similar fears.

The explorer Vladimir K. Arsenev also showed the Yellow Peril idea in Russia. This fear even continued into the Soviet era, leading to the forced movement of Koreans. Arsenev described East Asians (Koreans, Chinese, and Japanese) as a single "yellow peril." He criticized immigration to Russia and saw the Ussuri region as a barrier against this "onslaught."

Canada's Head Tax

Canada also had anti-Asian policies. The Chinese head tax was a fee charged to every Chinese person entering Canada. This tax started after the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 was passed. It was meant to stop Chinese people from coming to Canada after the Canadian Pacific Railway was finished.

The tax was ended by the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923. This new law completely stopped most Chinese immigration, except for certain groups like business people, religious leaders, teachers, and students.

United States' Policies

In 1854, Horace Greeley, an editor for the New-York Tribune, wrote an article supporting the idea of keeping Chinese workers out of California. He didn't use the term "yellow peril," but he compared Chinese workers to African slaves.

In California in the 1870s, even though a treaty allowed Chinese workers to come, white workers demanded that the U.S. government stop Chinese immigration. They felt Chinese workers were taking their jobs, especially during an economic downturn.

In Los Angeles, Yellow Peril racism led to the Los Angeles Chinese massacre of 1871. Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, a leader named Denis Kearney used the Yellow Peril idea in his speeches against Chinese workers. He often ended his speeches by saying, "and whatever happens, the Chinese must go!" The news often showed Asian people as a threat to American culture. This pressure led the U.S. government to pass the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which stopped Chinese immigration until 1943. After Kaiser Wilhelm II used the term in 1895, the U.S. press also started using "yellow peril" to describe Japan as a military threat and to talk about Asian immigrants.

Boxer Rebellion

In 1900, the Boxer Rebellion (August 1899 – September 1901) made the racist ideas of East Asians as a Yellow Peril even stronger. The Boxers were an anti-colonial group who believed Western countries were causing China's problems. They wanted to save China by killing Westerners and Chinese Christians. In the summer of 1900, the Boxers attacked foreign areas in Beijing.

Western Views

Most victims of the Boxer Rebellion were Chinese Christians. However, the Western world was more interested in getting revenge for the Westerners killed by the Boxers. In response, eight countries, including the United Kingdom, the United States, and Japan, formed the Eight-Nation Alliance. They sent soldiers to end the attacks in Beijing.

The Russian news described the Boxer Rebellion as a race and religious war between "White Holy Russia" and "Yellow Pagan China." They used quotes from anti-Chinese poems to support the idea of a Yellow Peril. Russian nobles also demanded action against the "Asian threat." Prince Sergei Nikolaevich Trubetskoy urged European leaders to divide China and end the Yellow Peril to Christian countries. Because of this, on July 3, 1900, Russia forced 5,000 Chinese people to leave Blagoveshchensk. From July 4 to 8, Russian police and soldiers killed thousands of Chinese people at the Amur River.

In the Western world, news of Boxer attacks caused Yellow Peril racism in Europe and North America. The Chinese rebellion was seen as a "race war" between the yellow race and the white race. The Economist magazine warned in 1905 that European powers needed to be careful when Chinese nationalism grew.

Colonial Revenge

On July 27, 1900, Kaiser Wilhelm II gave a racist speech called Hunnenrede. He told his soldiers to act like "Huns" and commit terrible acts against the Chinese people (both Boxers and civilians) to stop the rebellion. He said:

When you come before the enemy, you must defeat him, a pardon will not be given, prisoners will not be taken! Whoever falls into your hands will fall to your sword! Just as a thousand years ago the Huns, under their King Attila, made a name for themselves with their ferocity, which tradition still recalls; so may the name of Germany become known in China in such a way that no Chinaman will ever dare look a German in the eye, even with a squint!

The German Foreign Office tried to remove the parts about racist violence from the speech. But the Kaiser was annoyed and published the full speech. He saw the Boxer Rebellion as a war between the West and the East. However, his ideas about the Yellow Peril were much bigger than what was actually possible.

Orders for Cruelty

The Kaiser ordered his commander, Field Marshal Alfred von Waldersee, to be cruel. The Kaiser's friend, Philipp, Prince of Eulenburg, wrote that the Kaiser wanted to destroy Beijing and kill its people to get revenge for the murder of Germany's minister to China. Only the other nations in the Eight-Nation Alliance refused to be so cruel, which saved the people of Beijing from a massacre. In August 1900, soldiers from Russia, Japan, Britain, France, and America captured Beijing before the German forces arrived.

Acts of Cruelty

The eight-nation alliance looted and burned Beijing as revenge for the Boxer Rebellion. The level of destruction showed that the Western powers saw the Chinese as "less than human."

An American missionary named Luella Miner reported that Russian soldiers were "atrocious," the French were not much better, and the Japanese were looting and burning without mercy. German, Russian, and Japanese troops were criticized the most for their harshness and willingness to kill Chinese people of all ages, sometimes by burning entire villages. The Americans and British paid a Chinese general, Yuan Shikai, and his army to help the Eight-Nation Alliance stop the Boxers.

German Field Marshal Waldersee arrived in China on September 27, 1900, after the Boxers were already defeated. Still, he launched 75 attacks in northern China to find and destroy any remaining Boxers. His soldiers killed more farmers than Boxer fighters, because by autumn 1900, the Boxers were no longer a threat. In November 1900, a German politician named August Bebel criticized the Kaiser's attack on China, calling it shameful and barbaric.

Cultural Fears

The idea of Yellow Peril racism often called for white people around the world to unite. When there was an economic, social, or political problem, racist politicians would call for white unity against non-white people from Asia who they claimed threatened Western civilization. Even after the Western powers defeated the Boxer Rebellion, the fear of Chinese nationalism became a cultural concern among white people. They worried that the "Chinese race" wanted to invade and take over Christian civilization in the Western world.

Ideas of Racial Annihilation

The Darwinian Threat

An Austrian philosopher named Christian von Ehrenfels believed that the Western and Eastern worlds were in a "Darwinian racial struggle" for control of the planet. He thought the "yellow race" was winning. He claimed that Chinese people were inferior and that their culture lacked qualities like determination and invention, which he said were natural to white Western cultures.

Von Ehrenfels's racist idea was that if Asia conquered the West, it would mean the end of the white race. He imagined a genetically superior Sino–Japanese army taking over Europe after a race war that the West would lose.

Race War Ideas

To stop the Yellow Peril, von Ehrenfels suggested that white nations should unite. They should start a "preemptive war" to conquer Asia before it became too strong. Then, they would create a worldwide racial system, with the white race at the top in every conquered Asian country. He imagined a small group of "Aryan White people" leading the ruling class, military, and thinkers. In each conquered country, the Yellow and Black races would be slaves, forming the economic base of this worldwide racial system.

Xenophobia (Fear of Foreigners)

Germany and Russia

From 1895, Kaiser Wilhelm used the Yellow Peril idea to show Germany as the protector of the West against attacks from the East. He used this to get his government officials, the public, and other leaders to support his plans for Germany to become the most powerful empire. In a letter to Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, the Kaiser said: "It is clearly the great task of the future for Russia to cultivate the Asian continent, and defend Europe from the inroads of the Great Yellow Race."

Historian James Palmer explained that the idea of the "Yellow Peril" grew in the 1890s due to fears about Asian population growth, immigration to the West, and more Chinese people settling near the Russian border. These fears were mixed with a vague dread of mysterious powers supposedly held by followers of Eastern religions. A German picture from the 1890s, which inspired Kaiser Wilhelm II to coin the term, shows these ideas. It depicts European nations as heroic but vulnerable women, guarded by the Archangel Michael, looking anxiously at a dark cloud in the East. In the cloud, a calm Buddha is surrounded by flames.

The Kaiser knew that Tsar Nicholas shared his anti-Asian racism. He hoped to convince the Tsar to end his alliance with France and form a German–Russian alliance against Britain. Wilhelm II's use of the "yellow peril" was part of Germany's foreign policy. It aimed to encourage Russia's actions in Asia and later to create problems between the United States and Japan.

United States

19th Century Laws

In the U.S., Yellow Peril fears led to laws like the Page Act of 1875, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and the Geary Act of 1892. The Chinese Exclusion Act replaced an earlier treaty that had encouraged Chinese migration. That treaty had said that Chinese people in the U.S. and Americans in China should have religious freedom and not face unfair treatment.

In the Western U.S., Chinese people were often treated unfairly, leading to the saying, "Having a Chinaman's chance in Hell," meaning "no chance at all." In Tombstone, Arizona, a sheriff and mayor formed an "Anti-Chinese League" in 1880. In 1880, a riot in Denver destroyed the local Chinatown. In 1885, the Rock Springs massacre destroyed a Chinese community in Wyoming. In Washington Territory, Yellow Peril fears led to attacks on Chinese workers, the burning of Seattle's Chinatown, and the Tacoma riot of 1885, where white residents forced Chinese people out of their towns. In Seattle, the Knights of Labor forced 200 Chinese people out in the Seattle riot of 1886. In Oregon, 34 Chinese gold miners were killed in the Hells Canyon Massacre (1887).

20th Century Laws

Due to political pressure, the Immigration Act of 1917 created an "Asian Barred Zone." People from these countries were not allowed to immigrate to the U.S. The Cable Act of 1922 said that American women could keep their citizenship even if they married, unless they married a non-white person who couldn't become a citizen. Asian men and women were not allowed to become American citizens.

The Cable Act also allowed the government to take away the citizenship of a white American woman if she married an Asian man. This law was challenged in the Supreme Court case Ozawa v. United States (1922). A Japanese-American man tried to prove that Japanese people were white and could become citizens. The Court ruled that Japanese people were not white. Two years later, the National Origins Quota of 1924 specifically stopped Japanese people from entering the U.S. and becoming citizens.

Protecting "American" Character

To "preserve the ideal of American homogeneity" (meaning keeping America mostly the same), the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924 limited who could enter the U.S. based on their skin color and race. The 1924 Act used old census data from 1890. This was because the 1890 data showed more white immigrants from Western and Northern Europe and fewer non-white immigrants from Asia and Southern/Eastern Europe. This helped protect the social, economic, and political power of white Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASPs) in the 1900s.

The National Origins Formula (1921–1965) aimed to keep the percentage of "ethnic populations" lower than the existing white populations. This meant only about 150,000 non-white people were allowed into the U.S. each year. This formula was later ended by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

Acceptable Asian Characters

In the 1930s, Yellow Peril stereotypes were common in U.S. culture. Movies showed Asian detectives like Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto. White actors played these Asian characters, making them acceptable to mainstream American audiences. This was especially true when the villains were secret agents from Imperial Japan.

People who supported the idea of a Japanese Yellow Peril in America included powerful groups who wanted to support the Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek. They presented him as a Christian Chinese savior. After Japan invaded China in 1937, these groups successfully pushed the U.S. government to help Chiang Kai-shek's side. News reports (in print, radio, and movies) favored China, which helped the U.S. fund and equip Chiang Kai-shek's anti-communist party against the Communist party led by Mao Zedong.

Changing Views During War

In 1941, after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government officially declared China an ally. The news media then changed how they used Yellow Peril ideas. They started including China with the West and criticized anti-Chinese laws as harmful to the war effort against Imperial Japan. The U.S. government hoped that after Japan was defeated, China would become a capitalist country led by Chiang Kai-shek.

Chiang Kai-shek asked the American government to get rid of anti-Chinese laws. He threatened to keep American businesses out of the "China Market" if they didn't. In 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was repealed. However, because another law from 1924 was still in place, this repeal was mostly a symbolic gesture of support for China.

21st Century Views

American professor Frank H. Wu said that anti-Chinese feelings today, pushed by people like Steve Bannon, are like the anti-Asian hatred from the 1800s. He called it a "new Yellow Peril." He noted that this view doesn't tell the difference between Asian foreigners and Asian-American U.S. citizens. He believes that American worry about China's rise comes from the fact that, for the first time in centuries, the Western world is challenged by a people they once saw as culturally behind and racially inferior. He suggests the U.S. sees China as "the enemy" because its economic success challenges the idea of white superiority. Also, the COVID-19 pandemic has increased xenophobia and anti-Chinese racism, which has deep roots in the Yellow Peril idea.

Australia

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, fear of the Yellow Peril was a common cultural feature among white people settling in Australia. This racist fear of non-white Asians was a main theme in novels about invasions, like The Yellow Wave: A Romance of the Asiatic Invasion of Australia (1895). These stories often imagined an Asian invasion of Australia's "empty north," which was actually home to Indigenous Australians. In one novel, White or Yellow?: A Story of the Race War of A.D. 1908 (1887), a journalist wrote about a large group of Chinese people legally arriving in Australia and taking over white society and industries.

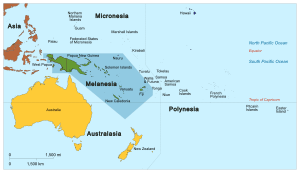

Stopping Racial Equality

In 1901, the Australian Government adopted the White Australia policy. This policy, which had been in place informally, generally stopped Asians, and especially Chinese and Melanesians, from immigrating. Historian C. E. W. Bean said this policy was "a strong effort to maintain a high, Western standard of economy, society, and culture." In 1913, a film called Australia Calls used the fear of the Yellow Peril. It showed a "Mongolian" invasion of Australia that was eventually defeated by ordinary Australians fighting secretly.

In 1919, at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes, supported by Britain and the U.S., strongly opposed Japan's request for a Racial Equality Proposal to be added to the Covenant of the League of Nations. This proposal stated:

The equality of nations being a basic principle of the League of Nations, the High Contracting Parties agree to accord, as soon as possible, to all alien nationals of states, members of the League, equal and just treatment in every respect, making no distinction, either in law or in fact, on account of their race or nationality.

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, who was the conference chairman, wanted to prevent official racial equality among nations. He said it needed a unanimous vote from all countries in the League of Nations. On April 11, 1919, most countries voted for the proposal, but the British and American delegations opposed it. To keep the White Australia policy, the Australian government sided with Britain and voted against Japan's request. This defeat in international relations greatly influenced Imperial Japan to later challenge the Western world militarily.

France

Colonial Empire

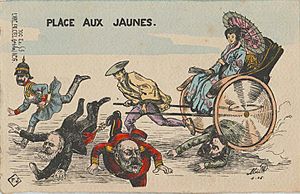

In the late 1800s, French politicians used the Péril jaune (Yellow Peril) to compare France's low birth-rate to the high birth-rates in Asian countries. This led to a cultural fear among the French that Asian immigrant workers would soon "flood" France. They believed the only way to fight this was for French women to have more children. This would give France enough soldiers to stop the future wave of immigrants from Asia. From this racist viewpoint, the French news supported Imperial Russia during the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905). They showed Russians as heroes defending the white race against the Japanese Yellow Peril.

In the early 1900s, in 1904, French journalist René Pinon wrote that the Yellow Peril was a cultural, political, and dangerous threat to white civilization. He described it as Japanese and Chinese groups spreading across Europe, destroying cities and civilizations. He believed that even if European countries stopped fighting each other, they would face a new danger: the "yellow man." He wrote that the civilized world always needed a common enemy, and for the future, it might be the "yellow man."

Despite claiming to bring civilization, the French exploited Vietnam's natural resources and treated the Vietnamese people as laborers from the start of colonization in 1858. After World War II, the First Indochina War (1946–1954) was justified as defending the white West against the péril jaune. They claimed that the Communist Party of Vietnam were puppets of China, part of a "communist plot" to conquer the world. French anti-communism used racist ideas to dehumanize the Vietnamese, allowing cruel acts against prisoners during the "dirty war." This Yellow Peril racism was a reason for the existence of French Indochina. French news often showed Vietnamese fighters as "innumerable yellow hordes" or "fanatical hordes."

Modern France

In her 1991 book, Gisèle Luce Bousquet said that the péril jaune, which shaped how the French saw Asians, especially Vietnamese people, is still a cultural prejudice in modern France. French people sometimes resent Vietnamese people in France, seeing them as academic overachievers who take jobs from "native French" people.

In 2015, the cover of Fluide Glacial magazine showed a cartoon called Yellow Peril: Is it Already Too Late?. It showed a Chinese-occupied Paris with a sad Frenchman pulling a rickshaw, carrying a Chinese man in a 19th-century French colonial uniform, with a blonde French woman. The editor defended it as satire about French fears of China's economic threat. He even joked about printing more copies to help balance France's trade deficit.

Italy

In the 1900s, Imperial Japan and Ethiopia worked together to avoid being colonized by European powers. Before the Second Italo-Ethiopian War (1934–1936), Japan gave diplomatic and military support to Ethiopia against an invasion by Fascist Italy. In response, Benito Mussolini ordered a Yellow Peril propaganda campaign in the Italian news. This campaign showed Japan as a military and cultural threat to the Western world. It warned of a dangerous "yellow race–black race" alliance meant to unite Asians and Africans against white people.

In 1935, Mussolini warned about the Japanese Yellow Peril and the threat of Asia and Africa uniting against Europe. In the summer of 1935, the National Fascist Party often held anti-Japanese protests in Italy. However, Japan and Italy, both powerful empires, eventually agreed to disagree. Japan would not help Ethiopia against Italy if Italy recognized Manchukuo, a Japanese-controlled state in China. Italy then stopped its anti-Japanese Yellow Peril propaganda.

Mexico

During the Mexican Revolution (1910–20), Chinese-Mexicans faced racist abuse. They were criticized for not being Catholic, for not being "Mexican" racially, and for not fighting in the Revolution.

A terrible event against Asian people was the Torreón massacre (May 13–15, 1911) in northern Mexico. Soldiers killed 308 Asian people (303 Chinese, 5 Japanese) because they were seen as a threat to Mexican culture. In 1913, after capturing the city of Tamasopo, soldiers and townspeople forced the Chinese community out by looting and burning their Chinatown.

During and after the Mexican Revolution, Yellow Peril ideas, often linked to Catholic beliefs, led to racism and violence against Chinese Mexicans. They were often accused of "stealing jobs." Anti-Chinese propaganda falsely claimed that Chinese people were unclean, immoral, and spread diseases that would harm the "Mexican race." In the 1930s, about 70% of the Chinese and Chinese-Mexican population was forced out of Mexico.

Turkey

In 1908, near the end of the Ottoman Empire, the Young Turk Revolution brought the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) to power. The CUP admired Japan's modernization during the Meiji Restoration (1868) because Japan modernized without losing its identity. The CUP wanted to make Turkey the "Japan of the Near East." They even thought about allying with Japan to unite Eastern peoples in a "racial war" against the white colonial empires of the West. In Turkish culture, the "yellow" color of "Eastern gold" symbolizes the moral superiority of the East over the West, which supported these ideas.

Fear of the Yellow Peril still happens against Chinese communities in Turkey. This is often in response to the Chinese government's actions against the Muslim Uyghur people in China's Xinjiang province.

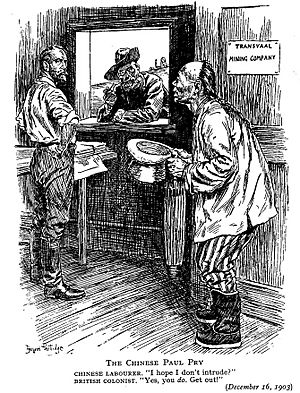

South Africa

In 1904, after the Second Boer War, the British government allowed about 63,000 Chinese laborers to come to South Africa. They were brought to work in the gold mines for lower wages.

On March 26, 1904, about 80,000 people protested in London against using Chinese laborers in South Africa. They wanted to highlight the exploitation of these workers. The Trade Union Congress passed a resolution saying that the government was wrong to allow "indentured Chinese labor under conditions of slavery."

The large number of Chinese laborers working for low wages in South Africa contributed to the British government's election loss in 1906. After 1910, most Chinese miners were sent back to China because of strong opposition to them as "colored people" in white South Africa. Despite the racial violence between white and Chinese miners, the use of Chinese labor helped South Africa's economy recover after the war, making the gold mines very productive.

New Zealand

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Prime Minister Richard Seddon used the Yellow Peril idea to promote racist politics in New Zealand. He compared Chinese people to monkeys. In his first political speech in 1879, Seddon said New Zealand didn't want its shores "flooded with Asiatic Tartars." He added, "I would sooner address white men than these Chinese. You can't talk to them, you can't reason with them. All you can get from them is 'No savvy'."

In 1905, in Wellington, a white supremacist named Lionel Terry murdered an old Chinese man, Joe Kum Yung. He did this to protest Asian immigration. Laws were passed to limit Chinese immigration, including a heavy poll tax in 1881. This tax was lowered in 1937 after Imperial Japan invaded China. In 1944, the poll tax was removed, and the New Zealand government formally apologized to the Chinese people of New Zealand.

Yellow Peril in Stories and Movies

Novels

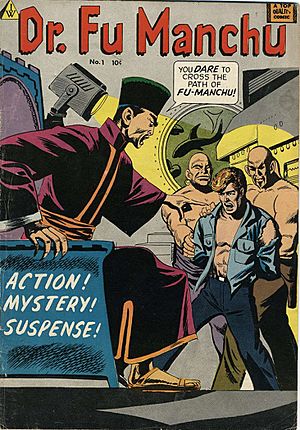

The Yellow Peril was a common theme in adventure stories of the 1800s. Dr. Fu Manchu is a famous villain from these stories, created by Sax Rohmer. Fu Manchu is a mad scientist who wants to conquer the world, but he is always stopped by a British policeman, Sir Denis Nayland Smith.

Yellow Peril: The Adventures of Sir John Weymouth–Smythe (1978) by Richard Jaccoma is a story that imitates the Fu Manchu novels.

The novel Yellow Peril (1989) by Bao Mi (Wang Lixiong) describes a civil war in China that leads to nuclear war, then escalates into World War III. Published after the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, this book showed ideas against the Chinese government and was therefore banned.

Short Stories

- The Infernal War (1908) by Pierre Giffard is a science fiction story. It shows World War II as a fight among white European empires. This distraction allows China to invade Russia and Japan to invade the U.S.

- In "Under the Ban of Li Shoon" (1916) and "Li Shoon's Deadliest Mission" (1916), H. Irving Hancock created the villain Li Shoon. He was described as a "tall and stout" man with a "moon-like yellow face" and "bulging eyebrows" over "sunken eyes." Li Shoon was seen as a mix of evil and intelligence, making him "a wonder at everything wicked."

- The Peril of the Pacific (1916) by J. Allan Dunn describes a made-up Japanese invasion of the U.S. mainland in 1920. This invasion happens with the help of disloyal Japanese-Americans and the Imperial Japanese Navy. The racist language in the story shows the strong, irrational fear of Japanese-American citizens in California at the time.

- "The Unparalleled Invasion" (1910) by Jack London, set between 1976 and 1987, shows China conquering other countries. The Western World fights back with biological warfare. Western armies kill Chinese refugees at the border and survivors in China. London describes this war as necessary for white people to settle China.

- In "He" (1926) by H. P. Lovecraft, a white man sees the future where "yellow men" dance among the ruins of the white man's world. In "The Horror at Red Hook" (1927), the story talks about "slant-eyed immigrants" in New York practicing "nameless rites in honor of heathen gods."

Yellow Peril in Movies

In the 1930s, Hollywood movies showed two different images of East Asian men: the evil master-criminal, Dr. Fu Manchu, and the good master-detective, Charlie Chan. Fu Manchu was a character that played on fears of Asian people spreading and taking over.

In 1936, the Nazis banned Sax Rohmer's novels in Germany because they thought he was Jewish. Rohmer denied being racist and said his stories were "not against Nazi ideals." In science fiction movies, the "futuristic Yellow Peril" is shown by Emperor Ming the Merciless, a character like Fu Manchu who fights Flash Gordon. Similarly, Buck Rogers fights against the Mongol Reds, a Yellow Peril group that took over the U.S. in the 25th century.

Yellow Peril in Comic Books

In 1937, DC Comics featured "Ching Lung" on the cover of Detective Comics. Years later, in New Super-Man (2017), it was revealed that Ching Lung was actually All-Yang, the evil twin brother of I-Ching. He created the Ching Lung image to show Super-Man how the West made Chinese people look like villains.

In the late 1950s, Atlas Comics (now Marvel Comics) published Yellow Claw, a story similar to Fu Manchu. What was unusual for the time was that the racist imagery was balanced by an Asian-American FBI agent, Jimmy Woo, who was the main opponent.

In 1964, Stan Lee and Don Heck created the Mandarin in Tales of Suspense. He was a supervillain inspired by the Yellow Peril idea and was the main enemy of Iron Man. In Iron Man 3 (2013), the Mandarin appears as the leader of a terrorist group. Iron Man discovers that the Mandarin is actually an English actor hired as a cover for someone else's crimes. The filmmakers said they made the Mandarin an impostor to avoid Yellow Peril stereotypes and to show how fear is used by powerful groups.

In the 1970s, DC Comics introduced Ra's al Ghul, a supervillain similar to Fu Manchu. While his race was not clearly stated, his beard and "Chinaman" clothing made him an example of Yellow Peril stereotyping. When adapting the character for Batman Begins, the filmmakers had an impostor Ra's al Ghul to distract from the true character. This was done to avoid the problematic origins of the character, making the villain a deliberate fake rather than a real portrayal of another culture's evil plans.

Marvel Comics used Fu Manchu as the main enemy of his son, Shang-Chi. Later, Marvel Comics lost the rights to the Fu Manchu name, so his real name became Zheng Zu. The Marvel movie Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings (2021) replaces Fu Manchu with Xu Wenwu, a new character inspired by Zheng Zu and the Mandarin. This movie lessens the Yellow Peril ideas because Wenwu is fought by an Asian superhero, his son Shang-Chi, instead of Tony Stark. It also removes any direct references to the Fu Manchu character.

See also

In Spanish: Peligro amarillo para niños

In Spanish: Peligro amarillo para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |