Battle of Kunersdorf facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Kunersdorf |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Third Silesian War | |||||||

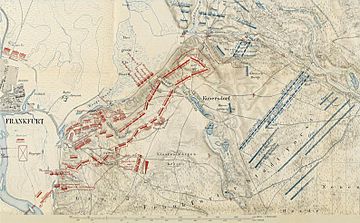

Battle of Kunersdorf, Alexander Kotzebue |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 59,500 248 guns |

50,900 230 guns |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 16,332 | 18,609–20,700 172 guns |

||||||

The Battle of Kunersdorf happened on August 12, 1759. It took place near Kunersdorf (now Kunowice, Poland). This battle was a major part of the Third Silesian War and the larger Seven Years' War.

Over 100,000 soldiers fought in this battle. An army of Russians and Austrians, led by Pyotr Saltykov and Ernst Gideon von Laudon, defeated Frederick the Great's Prussian army. The Allied forces had about 59,500 soldiers, while Frederick had around 50,900.

The land around Kunersdorf made fighting difficult for both sides. However, the Russians and Austrians arrived first. They used the tough terrain to their advantage by building strong defenses. They also prepared for Frederick's famous "oblique order" attack.

Even though Frederick's troops started strong, the large number of Allied soldiers eventually gave the Russians and Austrians the upper hand. By the afternoon, the Prussian army was exhausted. Fresh Austrian troops joined the fight, securing a victory for the Allies.

This battle was the only time in the Seven Years' War that the Prussian Army, led by Frederick himself, completely fell apart. After this loss, Berlin, the capital of Prussia, was only 80 kilometers (50 miles) away. It was open to attack by the Russians and Austrians. However, the Allied commanders did not follow up on their victory due to disagreements.

Only about 3,000 soldiers stayed with Frederick after the battle. Many more had scattered but rejoined the army within a few days. This was one of Frederick's worst defeats.

Contents

Understanding the Seven Years' War

Why the War Started

The Seven Years' War was a huge global conflict. In Europe, it was closely linked to the earlier War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). After that war, Frederick II of Prussia, also known as Frederick the Great, gained control of a rich area called Silesia. This happened after the First and Second Silesian Wars.

Empress Maria Theresa of Austria wanted Silesia back. She also wanted to regain power in the Holy Roman Empire. So, she rebuilt her army and made new alliances. In 1754, problems between Great Britain and France in North America gave France a chance to challenge Britain's control of Atlantic trade.

Maria Theresa saw this as an opportunity. She put aside her old rivalry with France to form a new team against Prussia. Because of this, Britain joined forces with Prussia. This series of political changes is known as the Diplomatic Revolution.

Prussia's Early Successes

At the start of the war, Frederick had one of the best armies in Europe. His soldiers could fire their guns very quickly. By late 1757, Prussia was doing well in the war. They had won big battles at Rossbach and Leuthen. They also took back parts of Silesia that Austria had captured.

Prussia then moved south into Austrian Moravia. In April 1758, Prussia and Britain signed an agreement. Britain promised to send money and troops to help Frederick's army. These troops helped push the French out of Hanover and Westphalia.

While the French were busy, Prussia had to deal with Sweden, Russia, and Austria. All these countries wanted to take land from Prussia. Frederick was worried about the Russian army moving from the east. He marched to stop them.

In August 1758, a Prussian army of 35,000 men fought a Russian army of 43,000 at the Battle of Zorndorf. Both sides lost many soldiers, but the Russians pulled back. Frederick claimed victory. Later, a Swedish army stopped the Prussians at the Battle of Tornow. By the end of summer, the fighting was a draw.

Prussia's enemies did not fully push into Prussia's main territory. The Austrian commander, Leopold Josef Graf Daun, could have ended the war in October at Hochkirch. But he did not chase Frederick's army after his victory. This gave Frederick time to build a new army over the winter.

The Situation in 1759

By 1759, Prussia was mostly defending its land. Russian and Austrian troops were surrounding Prussia, getting close to Brandenburg. When winter ended in April 1759, Frederick gathered his army in Lower Silesia. This kept the main Austrian army in Bohemia.

However, the Russians moved their forces into western Poland. This threatened Prussia's heartland, even Berlin. Frederick sent his general, Friedrich August von Finck, to stop the Russians. But Finck's army was defeated at the Battle of Kay on July 23.

After this, Pyotr Saltykov and the Russian forces moved west. They took over Frankfurt an der Oder on July 31. There, they dug in and built defenses near Kunersdorf. To make things worse for the Prussians, an Austrian army led by Ernst Gideon von Laudon joined Saltykov in early August.

King Frederick quickly moved his army from Saxony. He combined his forces with the remaining troops of Carl Heinrich von Wedel. By August 9, Frederick had about 50,000 soldiers. He moved them towards the Oder River to face the Allied army.

Preparing for Battle

The Battleground

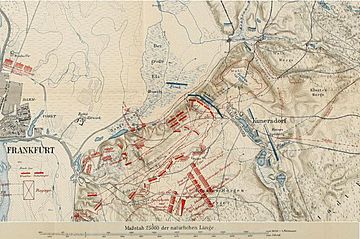

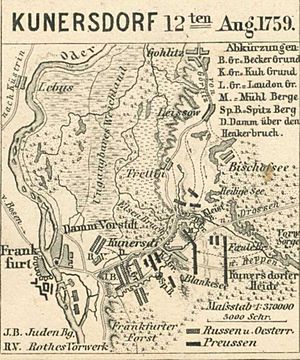

The land around Kunersdorf was better for defending than attacking. There was a line of small hills, like Judenberge and Mühlberge. These hills were about 30 meters (100 feet) high. They were steeper on the north side and bordered by a marshy area.

Several ravines and hollows cut through the hills. The ground was also covered with small ponds, streams, and marshy fields. These natural features made it hard for large armies to move around. To the east and north was the Forest of Reppen. The ground there was sandy and unstable, with many streams and bogs.

Allied Preparations

The Russian army had about 41,000 soldiers for the battle. The Austrian army had about 18,500 men. These numbers come from official records. Some older sources might have higher estimates, but they are not based on documents.

The Allied commanders, Saltykov and Laudon, did not always agree. Saltykov did not like foreigners, and Laudon found Saltykov hard to understand. They both mistrusted each other. But Laudon wanted to fight, so he helped the Russians build defenses.

Saltykov placed his troops in a strong position. He focused his forces in the center. He wanted to stop Frederick from using his "oblique order" attack. Saltykov built strong fortifications along the hills, facing northwest. The Judenberge hill was the most heavily defended.

They expected Frederick to attack from the west, from Frankfurt. To stop cavalry charges, the Russians used fallen trees to block the ground. Saltykov also took all the food and supplies he could from Frankfurt.

Prussian Plans

While Saltykov prepared, the Prussians reached Reitwein, north of Frankfurt, on August 10. They built temporary bridges across the Oder River during the night. Frederick crossed the river and moved south towards Kunersdorf. By August 11, the Prussians had about 50,000 men.

Frederick quickly looked at the enemy's position. He talked to a forest ranger and a local peasant. The peasant told him that a certain area was impassable. But the peasant did not know that the Russians had built a causeway there.

Looking through his telescope, Frederick saw the Reppen Forest. He thought he could use it to hide his army's movement, like he did at Leuthen. He did not send scouts to check the forest or ask locals about the ground. He also thought all the Allies were facing northwest.

Frederick planned to send a small force, led by Finck, to distract the Russians. His main army would march southeast, circling around Kunersdorf, hidden by the Reppen Forest. He hoped to surprise the enemy and force them to turn around. This would allow him to use his famous oblique battle order.

However, Saltykov was smart. Late on August 11, he realized Frederick was not attacking from Frankfurt. He changed his army's positions. The Russians then set fire to Kunersdorf. Only the stone church and some walls were left. Saltykov had outsmarted Frederick.

The Battle Unfolds

Prussian soldiers woke up at 2:00 am on August 12. They started marching within an hour. Finck's troops arrived at their position by dawn. Karl Friedrich von Moller set up artillery on a high hill and aimed it at the Russian lines. Finck's infantry and cavalry pretended to attack to distract the Russians.

Meanwhile, the rest of Frederick's army marched 37 kilometers (23 miles) in a semicircle. They went around the eastern side of the Russian line to attack from the southeast. This difficult march took up to eight hours. Frederick wanted to surprise the enemy, but he did not send any scouts to check the path.

Halfway through the march, Frederick realized he would face the enemy head-on, not from behind. Also, a row of ponds forced his army into three narrow columns. This made them vulnerable to Russian gunfire. Frederick changed his plans. His right vanguard would attack the Mühlberge hill. He hoped to push the Russians off the heights.

This redeployment took time. The delay confirmed Frederick's plan to Saltykov. The Russian commander moved more troops to face the Prussian attack.

Frederick's army got stuck in the Reppen Forest. It was a hot and humid day, and the men were already tired. The trees were thick, and the ground was soft and muddy. This made moving the heavy cannons very difficult. The carriages for the biggest guns were too wide for the narrow forest bridges. The soldiers had to rearrange their columns in the woods.

The Russians could hear them, but thought they were just small scouting groups. They believed Finck's column was the main force. Between 5:00 am and 6:00 am, only Finck's troops were visible to the Russians.

Attacking Mühlberge Hill

Finally, at 8:00 am, some of Frederick's army came out of the woods. This included most of Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz's cavalry and artillery. A short time later, the rest of the Prussians appeared. The Russians then realized it was the main army, not just scouts. The battle began in earnest.

Finck's artillery had been ready since dawn. At 11:30 am, Moller started firing at the Russian positions. The Russian artillery had been aimed incorrectly and had to be moved. For 30 minutes, both sides fired at each other.

Around noon, Frederick sent his first wave of soldiers towards the Russian position on the Mühlberge. These troops included grenadiers, musketeers, and cuirassiers. The Prussian artillery created a circle of fire, allowing the infantry to move safely. They advanced into a hollow between two hills. When they were very close to the Russian guns, they charged.

Some Russian troops on the hill suffered heavy losses. The Prussian grenadiers overwhelmed them. Prussian losses were also high. Frederick sent 4,300 men into this attack. He immediately lost 206 of Prince Henry's cuirassiers.

Saltykov sent his own grenadiers to help defend. But the Prussians captured the Mühlberge hill. They took between 80 and 100 enemy cannons. They immediately turned these cannons against the Russians. For a while, the Prussians held the position.

After taking the cannons, the Prussians fired at the retreating Russians with their own captured guns. Many Russians were killed or wounded. By 1:00 pm, the Russian left side was defeated and pushed back. Some Russians even accidentally fired on their allies, mistaking them for Prussians. Saltykov brought in more units, and the situation slowly became stable.

The Attack Stalls

The Prussian position was better, but the Russian position was much worse. While Frederick's main force attacked Mühlberg, Johann Jakob von Wunsch captured Frankfurt with 4,000 men. The Prussians had blocked the Allies from moving east, west, or south. The terrain blocked them from moving north. If they tried, Moller's artillery would hit them from the side.

Frederick's brother, Prince Henry, and other generals told Frederick to stop. They argued that the Prussians could defend Frankfurt from their position. To go down into the valley, cross the Kuhgrund, and attack the Spitzberge hills would be too risky. The weather was very hot, and the troops were tired from marching and fighting. They were also low on water and had not eaten a hot meal in days.

Despite these arguments, Frederick wanted to keep pushing. He had won half the battle and wanted a complete victory. He moved his artillery to the Mühlberg. He ordered Finck's troops to attack the Allied strong point from the northwest. His main force would cross the Kuhgrund.

To complete Frederick's plan, the Prussians had to go down one hill, cross a soft field, and then attack another well-defended hill. This is where Saltykov had placed most of his men, making the Grosser Spitzberg almost impossible to take.

Saltykov had already moved fresh troops, including most of Laudon's infantry, to reinforce this area. Finck's attack made no progress. The Prussian attack at the Kuhgrund was met with deadly fire along their narrow front. Saltykov watched and sent in more reinforcements from other areas.

The Allied forces had 423 artillery pieces, which they used against the struggling Prussians. The Allied grenadiers held their lines.

The Prussian left side had many problems, mostly because the terrain had not been properly checked. Two small ponds and several streams cut through the land. The Russians had also placed fallen trees to block the path. This forced the Prussian lines to break into small columns. This reduced their famous firepower.

Outside the Jewish settlement, the Prussians tried to break through the Russian line. They reached the Jewish cemetery but lost many men. For example, Krockow's 2nd Dragoons lost two-thirds of their force. Other regiments also had heavy losses. Despite these problems, they kept fighting through the Russian positions.

Cavalry Attack and Retreat

The battle ended in the early evening with a Prussian cavalry charge. It was led by von Seydlitz against the Russian center and artillery. This effort was pointless. The Prussian cavalry suffered huge losses from cannon fire and retreated in complete chaos. Seydlitz himself was badly wounded.

Dubislav Friedrich von Platen took command. Under Frederick's orders, Platen tried one last desperate attack. His scouts found a way past the ponds south of Kunersdorf. But it was in full view of the artillery on the Grosser Spitzberge. Seydlitz, still watching, knew it was foolish to charge a fortified position with cavalry. He was right, but Frederick seemed to have lost his clear judgment.

Prussian cavalry was known for attacking at a full gallop, with riders close together. But the ground was soft, marshy, and broken by streams. This forced them to attack in small groups, not in their usual massed formation.

Before more action could happen, Laudon led the Austrian cavalry in a counterattack. They routed Platen's cavalry. The fleeing Prussian men and horses trampled their own infantry. General panic spread through the Prussian army.

The cavalry attack against fortified positions had failed. The Prussian infantry had been on their feet for 16 hours. Half of that time was spent marching over difficult land. The other half was spent fighting against tough odds in hot weather. Despite the hopelessness, the Prussian infantry repeatedly attacked the Spitzberge, each time with greater losses. One infantry regiment lost over 90 percent of its force.

King Frederick himself led two attacks. He lost two horses in the effort. He was getting on a third horse when it was shot and fell, almost crushing him. Two of Frederick's helpers pulled him out. A bullet hit his gold snuff box, which, along with his heavy coat, probably saved his life.

The End of the Battle

By 5:00 pm, neither side could make any more progress. The Prussians held onto the captured artillery works. They were too tired to even retreat. They had pushed the Russians from the Mühlberge, the village, and the Kuhgrund, but no further.

The Allies were also tired, but they had more cavalry and some fresh Austrian infantry. These fresh troops, who had arrived late, joined the fight around 7:00 pm. For the exhausted Prussians, this wave of fresh Austrian reserves was the final blow.

Some Prussian groups fought bravely, but they suffered heavy losses. Their stubborn defense could not stop the chaos of the Prussian retreat. Soldiers threw away their weapons and ran for their lives.

The battle was lost for Frederick, though he had not accepted it yet. Frederick rode among his fleeing army, trying to rally his men. He grabbed a regimental flag and shouted, "Children, my children, come to me. With me, with me!" But they did not hear him, or they chose not to obey.

Saltykov sent his Cossacks and Kalmyks (cavalry) to finish the job. The Chuguevski Cossacks surrounded Frederick on a small hill. He stood there with the few remaining members of his bodyguard, determined to fight or die. With 100 hussars, Captain Joachim Bernhard von Prittwitz-Gaffron fought his way through the Cossacks. He dragged the King to safety. Many of his squadron died saving him.

Aftermath of the Battle

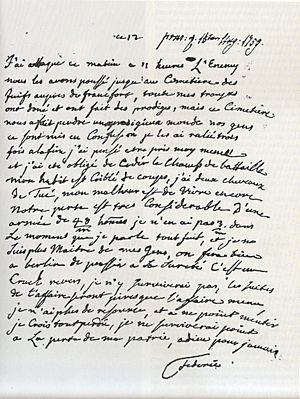

That evening, back in Reitwein, Frederick sat in a peasant hut. He wrote a desperate letter to his old tutor, Count Karl-Wilhelm Finck von Finckenstein: "This morning at 11 o'clock I have attacked the enemy. ... All my troops have worked wonders, but at a cost of countless losses. Our men got into confusion. I gathered them three times. In the end I was in danger of getting captured and had to retreat. My coat is full of bullet holes, two of my horses have been shot dead. My bad luck is that I am still living ... Our defeat is very big: I have 3,000 men left from an army of 48,000 men. Right now, everyone is running; I am no longer in charge of my troops. Thinking about the safety of anyone in Berlin is a good idea ... It is a cruel failure that I will not survive. The results of the battle will be worse than the battle itself. I do not have any more resources, and—to be honest—I believe that everything is lost. I will not survive the downfall of my homeland. Farewell forever!"

Frederick also decided to give command of the army to Finck. He told the general he was sick. He named his brother as the top commander. He also insisted his generals promise loyalty to his nephew, the 14-year-old Frederick William.

Battle Losses

Before the battle, both armies had received more troops. The Allied forces had about 60,000 men, plus 5,000 holding Frankfurt. The Prussians had almost 50,000.

The Russians and Austrians lost 16,332 men. About 3,486 were killed. Russian losses were 14,031, and Austrian losses were 2,301. Prussian losses vary in different sources. Some say 6,000 killed and 13,000 wounded, which is over 37 percent of their army. Other sources report 18,609 to 21,000 total losses.

The Prussians lost all their horse artillery. This was a special type of artillery where the crews rode horses, pulling their cannons. It was one of Frederick's inventions. The Prussians also lost 60 percent of their cavalry, both men and horses. They lost 172 of their own cannons. They also lost the 105 cannons they had captured from the Russians earlier. They lost 27 flags and two standards.

Many high-ranking officers were lost. Frederick lost eight regimental colonels. Seydlitz was wounded and had to give up command. Wedel was so badly wounded he never fought again. Georg Ludwig von Puttkamer, a cavalry commander, was killed. Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, who later became a major general in the American Revolutionary War, was wounded. Ewald Christian von Kleist, a famous poet and officer, was badly injured.

Several other generals died from their wounds later. Prussia was in a very difficult situation. Frederick felt hopeless about saving his kingdom for his heir.

Impact on the Allied Forces

Even though they were still careful of each other, the Russian and Austrian commanders were happy with their teamwork. They had outfought Frederick's army. Elizabeth of Russia promoted Saltykov and gave special medals to everyone involved. She also sent a sword of honor to Laudon.

However, the victory came at a high cost. Losing 27 percent of their men would not usually be considered a victory. The close-quarters fighting and cavalry charges caused many injuries and deaths on both sides.

Despite the losses, Saltykov and Laudon still had their armies intact. They also kept their communication lines open. But the Prussian defeat did not lead to bigger consequences. The victors did not march on Berlin. Instead, they went to Saxony.

Within days, Frederick's army regrouped. About 26,000 survivors were scattered between Kunersdorf and Berlin. But four days after the battle, most of them returned to headquarters. Frederick's army grew back to 32,000 men and 50 cannons.

Elizabeth of Russia continued to support Austria. She believed it was important for Russia. But her help became less effective. Long supply lines made it hard for Russian troops to get supplies. They took little part in the remaining battles of 1759 and 1760. The Russian army did not fight another major battle until 1761.

In 1762, Elizabeth died. Her nephew, Peter, who admired Frederick, became the new ruler. He immediately pulled Russia out of the war. This saved the Prussians.

Why Kunersdorf Was a Disaster

Most military historians agree that Kunersdorf was Frederick's biggest and most disastrous loss. They usually point to three main reasons:

- He did not respect the Russian way of fighting.

- He lacked good information about the land.

- He failed to realize that the Russians had overcome the terrain challenges.

Frederick made his situation worse by breaking his own rules of war.

Ignoring the Terrain and Enemy

First, Frederick thought he could use his famous "oblique order" attack. But his scouting was incomplete. The Russians had been there for two weeks. They had dug in and built strong defenses with fallen trees and cannons. When Frederick arrived, he did not properly check the land. He should have sent his cavalry to scout the area.

The Russians and Austrians had found and reinforced a causeway. This allowed them to create a strong, unified front. This canceled out any advantage of Frederick's oblique attack. Also, the Russians used the natural hills for defense. They built strong points and bastions. Even though Frederick's troops eventually pushed back the Russian left, it did little good. The terrain allowed the Allies to form a deep, strong line, protected by hills and marshes.

Refusing Advice

Second, Frederick made a big mistake by not listening to his trusted generals. His brother Henry, a skilled tactician, suggested stopping the battle at midday. By then, the Prussians had taken the first hill and Frankfurt. From these positions, the Prussians would be safe. Eventually, the Allied forces would have to retreat.

Henry also argued that the troops were exhausted. They had marched for days in very hot weather. They were low on water and had not eaten well. But instead of holding his safe position, Frederick forced his tired troops to go down the hill, cross low ground, and climb the next hill, facing heavy fire.

The Prussian cavalry initially pushed back the Russian and Austrian cavalry. But the heavy cannon and musket fire from the Allied front caused huge losses. Frederick also made a serious error by sending his cavalry into battle in small groups. He sent them against dug-in positions and over soft, marshy ground.

Breaking His Own Rules

Third, Frederick fought on ground chosen by his enemy, not his own. He had little information and almost no understanding of the land. He broke all his own military rules. He sent his infantry directly into heavy gunfire. He then made it worse by sending his cavalry in small, useless charges across soft, wet ground. The terrain made it impossible to send his cavalry in a large, powerful mass.

The huge loss was due to more than these three issues. Frederick broke his own rules because he disliked his enemies. This brought out the worst in his leadership. The loss at Kunersdorf was similar to the Battle of Hochkirch. At Hochkirch, Frederick's contempt for the Austrians led to his loss. This contempt for both Austrians and Russians also contributed to his defeat at Kunersdorf.

One historian noted that "seldom in military history has a battle been so completely lost by an organized army in such a short space of time." Frederick's loss was not just because he refused to believe his enemies had military skill. At Hochkirch, Frederick showed good leadership by rallying his troops. Prussian discipline held strong.

However, the Prussian army at Kunersdorf was not the same as the one at Hochkirch. Frederick had put together a new army over the winter. But it was not as well-trained or disciplined as his old one. He failed to accept this. At Kunersdorf, his army panicked, and discipline broke down, especially in the last hour. Only a few regiments held together. Frederick had demanded more from his men than they could give.

|

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |