Battle of Hochkirch facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Hochkirch |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Third Silesian War | |||||||

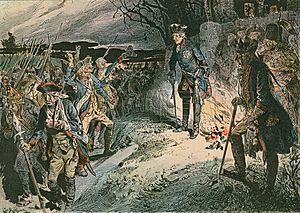

Der Überfall bei Hochkirch am 14. Oktober 1758, Hyacinthe de la Pegna |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 80,000 | 30,000–36,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 5,400 killed and wounded | 9,400 killed, wounded and captured | ||||||

The Battle of Hochkirch happened on October 14, 1758. It was a big fight during the Seven Years' War, specifically part of the Third Silesian War. After weeks of moving around, a large Austrian army of 80,000 soldiers, led by Leopold Josef Graf Daun, surprised the Prussian army. The Prussian army, with 30,000–36,000 soldiers, was led by Frederick the Great. The Austrians overwhelmed the Prussians, forcing them to retreat. The battle took place in and around the village of Hochkirch, about 9 kilometers (5.6 miles) east of Bautzen, in Saxony.

Many historians believe this battle was one of Frederick's biggest mistakes. He didn't listen to his officers. He refused to believe that the careful Austrian commander, Leopold von Daun, would actually attack. But the Austrian army ambushed his troops before dawn. Over 30% of Frederick's army was defeated. Five of his generals were killed, and he lost his cannons and many supplies. Even though Daun completely surprised them, he couldn't successfully chase the retreating Prussians. The Prussian soldiers who escaped joined another group nearby. They got their strength back over the winter.

Contents

What Was the Seven Years' War?

- Further information: Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War was a huge global conflict. In Europe, it was especially intense because of the recent War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). That war ended with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748. This treaty gave Frederick II of Prussia, also known as Frederick the Great, a rich area called Silesia.

Empress Maria Theresa of Austria signed the treaty to gain time. She wanted to rebuild her army and make new alliances. She was determined to regain power in the Holy Roman Empire and get Silesia back. In 1754, tensions grew between Britain and France in North America. This gave France a chance to challenge Britain's control of Atlantic trade. Austria saw this as an opportunity to get back its lost lands and limit Prussia's growing power. So, Austria and France, who used to be rivals, formed a new alliance. Britain then teamed up with the Kingdom of Prussia. This alliance included the British king's lands in Europe, like Hanover, and lands belonging to his relatives. This series of political moves was called the Diplomatic Revolution.

At the start of the war, Frederick had one of the best armies in Europe. His soldiers could fire their guns very quickly. By the end of 1757, the war was going well for Prussia and badly for Austria. Prussia won big victories at Rossbach and Leuthen. They also took back parts of Silesia that Austria had captured. The Prussians then moved south into Austrian Moravia. In April 1758, Prussia and Britain made an agreement called the Anglo-Prussian Convention. Britain promised to pay Frederick a lot of money each year. Britain also sent soldiers to help Frederick's brother-in-law, the Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. Ferdinand pushed the French out of Hanover and Westphalia. He also recaptured the port of Emden in March 1758. He crossed the Rhine River, which worried France. Even though Ferdinand won against the French at the Battle of Krefeld, he had to retreat back across the Rhine.

While Ferdinand kept the French busy, Prussia had to fight Sweden, Russia, and Austria. Prussia was worried about losing Silesia to Austria, Pomerania to Sweden, and other areas to Saxony or Russia. This was a nightmare for Prussia. By 1758, Frederick was concerned about the Russian army moving from the east. He marched to stop them. East of the Oder river in Brandenburg-Neumark, a Prussian army of 35,000 men fought a Russian army of 43,000. This was the Battle of Zorndorf on August 25, 1758. Both sides lost many soldiers, but the Russians pulled back. Frederick claimed victory. A month later, at the Battle of Tornow, a Swedish army pushed back the Prussians but didn't move on Berlin. By late summer, the fighting was a stalemate. None of Prussia's enemies seemed ready to attack deep into Prussia itself.

Before the Battle: A Game of Cat and Mouse

In September and early October 1758, the Austrian commander, Count Leopold Joseph von Daun, and his 80,000-man army camped near Stolpen. They had traveled 120 kilometers (75 miles) from Görlitz in just 10 days. Frederick had left half of his army near Zorndorf to keep the Russians busy. He then rushed south with the rest of his army to face Daun in Saxony. Frederick and his army, now 45,000 strong, were ready to fight. Frederick called Daun "the fat Excellency."

Between Bautzen and Löbau, Frederick and Daun played a game of cat and mouse. Frederick tried many times to get the Austrians to leave Stolpen and fight. But Daun, who rarely attacked unless he had a perfect plan, refused to take the bait. Frederick and his army marched very close to the Austrians. But Daun moved his army away again, still refusing to fight. When the Austrians pulled back, Frederick sent troops to chase them. These were driven off by Daun's rear guard. Frustrated, Frederick followed Daun by moving his army toward Bautzen. There, Frederick learned that Daun had set up camp about 5 kilometers (3 miles) east of him, in the hills near Hochkirch. He sent a Prussian group led by General Wolf Frederick von Retzow to those hills in late September. By early October, Retzow's group was very close to the Austrians. Frederick ordered Retzow to take a hill called Strohmberg. But when Retzow arrived, he found the Austrians already had a strong force there. Retzow chose not to attack. Frederick removed him from command and had him arrested.

Setting Up for Battle

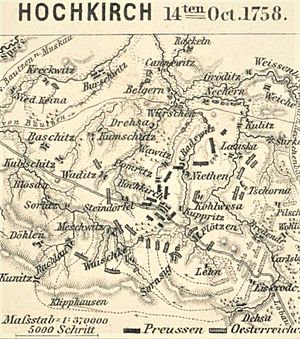

Hochkirch is on a small hill, surrounded by gently rolling plains. You can see the village from far away, except from the south. There, some hills block the view. The church is near the highest point, offering views to the east, west, and north.

On October 10, Frederick marched to Hochkirch and set up his own camp. It stretched from the town north for 5 kilometers (3 miles) to the edge of a forest. Frederick didn't plan to stay long in the small village. He just wanted to wait for supplies, mainly bread, from Bautzen. Then they would move east. To the east of the village, less than 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) away, the Austrians were on a hilltop. This made the Prussians, except Frederick, worried about an attack. One of Frederick's generals, Keith, told him, "If the Austrians leave us alone in this camp, they deserve to be hanged." Frederick reportedly replied, "It is to be hoped they are more afraid of us than of the gallows."

Instead of worrying about an Austrian attack, Frederick spread out his men facing east. This was where Daun's army was last seen. The troops formed an S-shaped line, north to south, next to Hochkirch. The weaker west side was guarded by a small group of nine battalions with cannons. Their main job was to stay in touch with a scouting unit. Eleven battalions and 28 cavalry units guarded the east side. Frederick put his best soldiers in the village of Hochkirch. He didn't think an attack would happen. Daun's army had been quiet for months, refusing to fight.

The royal court in Vienna criticized Daun for not acting. The Empress and her ministers worried that the Russians and French would leave their alliance if there was no action. Daun, a careful commander, took his time to make his plans. A hill next to Hochkirch, called Strohmberg, was on Daun's left side. He spread the rest of his army south across the road between Bautzen and Loebau. This also gave him control of an important road junction. He placed the far right end of his line on another wooded hill south of the road, the Kuppritzerberg. This was on the opposite side of the hill from the Prussians. Even though they were close, the Prussians didn't increase their security or move their troops in response to the Austrians. The cautious Daun also knew his men were eager to fight. They also outnumbered the Prussians by more than two to one. His men made a big show of cutting down trees in a nearby forest. Frederick thought they were building defenses. But they were actually building a road through the thick woods. Daun also found out a secret weakness of Frederick's. His own personal secretary had been sending Frederick information about Daun's plans, hidden in egg deliveries. When Daun found out, he promised the man his life if he helped send Frederick false information. Daun's secret plan was an early morning attack. He would sweep through the woods with 30,000 specially chosen troops. They would go around Frederick's side to surround him. The Prussian army would be asleep when the Austrian army attacked.

The Battle Begins: A Surprise Attack

Daun's battle plan completely surprised the Prussians. The east side of Frederick's line was attacked first. Using the dark, starless night and fog as cover, the Austrians attacked the Prussian cannons. They were grouped into small units for better control and stealth. The church bell rang at 5:00 AM, and the Austrians caught the Prussians totally off guard. Many soldiers were still sleeping or just waking up when the attack began. After setting the village on fire, the Croats cut the tent ropes. This made the tents fall on sleeping soldiers. Then they used bayonets to attack the men as they struggled to get free. Soldiers tangled in the tents bled to death in what is still called Blutgasse, or Blood Alley, today.

At first, Frederick thought the sounds of battle were just a small fight or the Croats, who often fired their weapons in the morning. His staff had trouble waking him up. But he was soon alerted when Prussian cannons, captured by the Austrians, started firing on his own camp.

While Frederick's helpers tried to wake him, his generals organized the Prussian defense. Most of them hadn't slept and had kept their horses ready. General Keith had expected an Austrian attack. He organized a strong counterattack on the Austrians holding the Prussian cannons. Maurice von Anhalt-Dessau, another of Frederick's skilled generals, sent the waking troops to Keith. Together, they briefly took back the Prussian cannons south of Hochkirch. But they couldn't hold it against the Austrian guns. At 6:00 AM, three more Prussian regiments rushed into Hochkirch itself. Prince Maurice kept directing scattered soldiers and reinforcements into the counterattack. The Prussians swept through the village, out the other side, and attacked the cannons with bayonets. By then, however, most Prussian order was lost. The Austrians, using the captured Prussian guns, caused a lot of damage to the attackers. Keith was hit in the middle of his body and fell from his horse, dead.

When the early morning fog lifted, the soldiers could tell friends from enemies. Prussian cavalry, who had stayed ready all night, launched a series of counterattacks. A battalion of the 23rd Infantry charged but pulled back when they were surrounded. The churchyard, a strong walled area, distracted the Austrians. Major Siegmund Moritz William von Langen's musketeers held it bravely. This gave safety to retreating Prussians. Most importantly, Langen bought time.

By this time, Frederick was fully awake. He hoped the battle could still be won. He returned to the village to take command. At 7:00 AM, finding his infantry confused in the village, Frederick ordered them to advance. He sent reinforcements led by Prince Francis of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, his brother-in-law, with them. As Francis approached the village, Austrian cannon-fire hit him, taking off his head. His troops hesitated, shocked by the sight of the prince's headless body on his spooked horse. Frederick himself helped to rally Francis's shaken troops.

By 7:30 AM, the Austrians had retaken the burning village, but their hold was weak. Keith and Prince Francis were dead. General Karl von Geist was among the injured. Maurice von Anhalt-Dessau had been injured and captured. By 9:00 AM, the Prussian left side began to collapse under the strong Austrian attack. The last Prussian cannons were captured and turned against them. Led by the King, they advanced against five Austrian groups of hussars led by Franz Moritz von Lacy. Within a few yards of the Austrian infantry line, Frederick's horse was killed. His own hussars saved him from being captured.

As he pulled back, Frederick set up a fighting line north of the village. This became a place for scattered soldiers and survivors to gather. By mid-morning, around 10:00 AM, the Prussians retreated to the north-west. Any chasing troops were met with a wall of gunfire. Frederick and his remaining army were out of reach of the Austrian army by the time they had reorganized. Hans Joachim von Zieten and Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz, who had also stayed alert all night, organized a rear guard action. This stopped the Austrians from attacking the retreating Prussians. This discouraged even the most determined Austrians. The Croats and other irregular soldiers were happy to just loot the village and the dead Prussian bodies.

What Happened After the Battle?

In just five hours, Frederick lost 9,400 of the 30,000 men he brought to the battle. This was more than 30% of his army. This included five generals, 101 cannons, and almost all their tents. Frederick expected his generals to show courage and leadership. They led from the front. Many officers were also lost. In addition to human losses, they lost valuable horses and supply wagons. They also lost 28 flags, which was a blow to their spirits. On the good side, Retzow's group of about 6,000 men, who hadn't arrived in time to fight, remained untouched. Frederick had gathered his troops for an organized retreat. The King also kept the trust of his soldiers.

The Austrians lost about three percent of their soldiers. According to one historian, the Austrian losses were about 5,400 killed or wounded. They also lost three flags. Some modern historians say the total losses were higher, around 7,300. News of the battle reached Vienna during a celebration for the Empress's name day. Maria Theresa and her court were very happy. Daun received a special blessed sword and hat from Pope Clement XIII. This reward was usually given for defeating "non-believers." The Empress later gave Daun and his family a large sum of money.

For Daun and Lacy, it was a victory with mixed feelings. When they found Keith's body in the village church, they both cried. Keith had been the best friend of Lacy's father when he served in Russia. Frederick also felt intense sadness at losing one of his greatest friends. His grief grew when he learned a few days later that his beloved older sister, Wilhelmine, had died on the same day. He stayed in his tent for a week.

Even though Frederick showed good leadership by rallying his troops, Hochkirch is seen as one of his worst losses. It deeply affected him. Andrew Mitchell, the British envoy who was with them, usually wrote good things about Frederick. But he blamed Frederick's loss on his disrespect for Daun's careful nature. He also blamed Frederick for not believing information that didn't match what he thought was true. Mitchell said there was no one to blame but Frederick himself. That winter, Mitchell described the 46-year-old Frederick as "an old man lacking half of his teeth, with greying hair, without gaiety or spark or imagination." Frederick suffered from gout and the flu. He refused to change his uniform, which was old and stained.

However, the situation could have been much worse for Frederick. His army's famous discipline held up. Once the Prussians were out of the burning village, their unit order and discipline returned. Their discipline stopped the Austrians from gaining any big advantage. Daun's hesitation canceled out the rest. Instead of following Frederick, or cutting off Retzow's group, which hadn't fought, Daun went back to the hills he had held before the battle. He wanted his men to rest after the day's fighting. After staying there for six days, they secretly marched to a new position. Frederick remained at Doberschütz. In the end, the costly Austrian victory didn't decide anything big.

The Austrian failure to follow up with Frederick meant the Prussians lived to fight another day. Daun was criticized a lot for this, but not by the most important people, the Empress and her minister Kaunitz. For Frederick, instead of the war ending at Hochkirch, he had the chance over the winter to rebuild his army. In two years of fighting (1756–1757), Frederick had lost over 100,000 soldiers to death, wounds, capture, disease, and desertion. By Hochkirch, many regiments were only half-trained. In the winter after Hochkirch, he could only replace his soldiers with untrained men. Many of these would be foreigners and prisoners of war. He would start 1759 with a half-trained army of new recruits and tired, experienced soldiers. The only way he could hire men was with British money.

Frederick's reputation for being aggressive still scared the Austrians. On November 5, the anniversary of his great victory at Rossbach, Frederick marched toward Neisse. This made the Austrians abandon their siege. A few weeks later, as Frederick marched further west, Daun took his entire army into winter camps in Bohemia. So, despite major losses, at the end of the year, Frederick still controlled Saxony and Silesia. His name was still feared in that part of Europe.

Memorials

A granite monument with a bronze plaque was put up by the people of Hochkirch. It remembers "Generalfeldmarschall Jacob von Keith" and his bravery. The inscription says "Suffering, Misery, Death."

- Memorials

- Hochkirch and environs

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |