Battle of Roncevaux Pass facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Roncevaux Pass |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Charlemagne's campaign in the Iberian Peninsula | |||||||

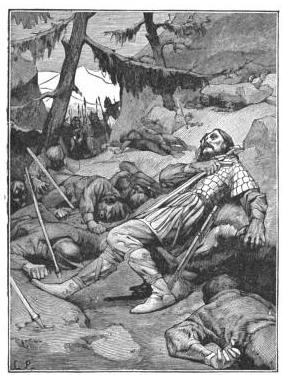

A 15th-century painting showing the Battle of Roncevaux Pass |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Franks | Basques Andalusians |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Charlemagne Roland † |

Unknown (Some think it was Lupo II of Gascony or Bernardo del Carpio) Ayxun ibn Sulayman ibn Yaqdhan al-Arabí Matruh al-Arabi |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| About 3,000 soldiers crossing the pass | Unknown, but a large force | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| The entire rearguard was killed | Unknown | ||||||

The Battle of Roncevaux Pass was a famous battle that took place on August 15, 778. In a high mountain pass in the Pyrenees, a large force of Basque warriors ambushed part of the army of the great Frankish king, Charlemagne.

The attack was a surprise. As Charlemagne's army was heading back to France, the Basques attacked the rearguard. The rearguard is the part of the army that travels at the very back to protect everyone else. The Franks were caught off guard and completely defeated in a last stand.

One of the commanders who died in the battle was Roland. His bravery turned him into a legendary hero. Stories and poems were written about him, like the famous The Song of Roland. These tales about Roland and his fellow warriors, known as paladins, helped shape the idea of the perfect knight and the code of chivalry during the Middle Ages.

Contents

Why Was Charlemagne's Army in Spain?

In the 8th century, the Carolingians were a powerful family of kings, and Charlemagne was their most famous ruler. He wanted to expand his kingdom, which was called Francia.

At the time, much of the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain and Portugal) was ruled by the Umayyad emir of Córdoba, Abd ar-Rahman I. Some local governors in the north of Spain were unhappy with his rule. One of them, Sulayman al-Arabi, the governor of Barcelona, asked Charlemagne for help. He promised that if Charlemagne brought his army to Spain, several cities, including the important city of Zaragoza, would surrender to him.

Seeing a chance to grow his empire and spread Christendom, Charlemagne agreed. In 778, he led a huge army across the Pyrenees mountains into Spain. At first, things went well. But when he reached Zaragoza, the city's ruler, Husayn, refused to surrender. He had never promised to give his city to Charlemagne.

After a month of trying to capture the city, Charlemagne made a deal. Husayn gave him gold and some prisoners, and in return, Charlemagne and his army would leave.

The Ambush in the Mountains

Before heading back to France, Charlemagne made a decision that would lead to disaster. To make sure he controlled the Basque lands he was passing through, he ordered his army to tear down the city walls of the Basque capital, Pamplona. He may have feared the Basques would use the strong walls against him in the future. This act greatly angered the Basque people.

A Surprise Attack

As Charlemagne's army marched through the narrow Roncevaux Pass in the Pyrenees, the enraged Basques were waiting. They knew the mountains perfectly and used this knowledge to set up a trap.

On the evening of August 15, the Basque warriors launched a surprise attack on the Frankish rearguard. The rearguard was protecting the army's retreat and its baggage train, which was full of supplies and treasure. The Franks were caught completely by surprise in the difficult, rocky terrain.

The Basques, positioned on higher ground, threw rocks and spears down on the Franks. They cut off the rearguard from the main army. Roland and the other famous lords in the rearguard fought bravely, but they were outnumbered and in a terrible position. They fought to the last man, but in the end, the entire rearguard was wiped out. Their sacrifice allowed the rest of Charlemagne's army to escape. The Basques took the treasure from the baggage train and disappeared into the mountains as darkness fell.

The Basque Warriors

The Basque warriors were not heavily armored like the Frankish knights. They were mountain fighters who used guerrilla tactics. They were typically armed with short spears, knives, and bows or javelins. They were fast, knew the land, and used the element of surprise to defeat a stronger army.

Some historians believe the attack was led by Lupo II of Gascony, a Basque duke who ruled the lands in the Pyrenees. He may have been unhappy with Charlemagne trying to take control of his territory.

What Happened After the Battle?

The Battle of Roncevaux Pass was the only major defeat Charlemagne ever suffered in his long military career. He lost many of his best soldiers, including important nobles like Roland, and a large amount of treasure.

Charlemagne never again led an army into Spain himself. However, the Franks did not give up on the region. To protect his empire from future attacks, Charlemagne created a special buffer zone south of the Pyrenees called the Marca Hispanica. Over the next few years, his generals captured more territory, including Barcelona.

The Basques, however, continued to fight for their freedom. The battle helped them unite and eventually form their own independent kingdom, the Kingdom of Pamplona (later known as Navarre), in 824. In that same year, the Basques defeated another Frankish army at the very same pass in the second Battle of Roncevaux Pass.

From a Real Battle to a Famous Legend

Over time, the story of the battle was romanticized and changed. The real battle was between the Christian Franks and the mostly pagan Basques. But in the legends, the Basques were replaced by a huge army of 400,000 Saracens (a medieval term for Muslims).

The most famous work about the battle is The Song of Roland. It is an epic poem written in the 11th century and is one of the oldest great works of French literature. In the poem, Roland is the perfect Christian knight. He has a magical, unbreakable sword named Durendal and a horn called an Oliphant. He blows the horn to warn Charlemagne, but he dies a hero's death.

The story of Roland and his paladins became a model for how knights were expected to behave. It helped create the code of chivalry, which valued bravery, loyalty, and honor. The poem was so popular that soldiers under William the Conqueror chanted it before the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

Today, the battle is remembered with monuments in the Pyrenees. There is even a gap in the mountains called Roland's Breach, which legend says Roland cut with his sword. The story has inspired books, operas, and movies for centuries.

See also

- Duchy of Vasconia

- Kingdom of Navarre

- Roland's Breach