Bedford–Stuyvesant, Brooklyn facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Bedford–Stuyvesant

|

|

|---|---|

|

Neighborhood of Brooklyn

|

|

|

|

| Nicknames:

Bed-Stuy, Do or Die

|

|

| Country | |

| State | |

| City | New York City |

| Borough | Brooklyn |

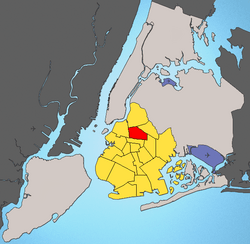

| Community District | Brooklyn 3, Brooklyn 8 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7.21 km2 (2.782 sq mi) |

| Population

(2011)

|

|

| • Total | 157,530 |

| • Density | 21,863/km2 (56,625/sq mi) |

| Ethnicity | |

| • Black | 45.6% |

| • White | 29.4% |

| • Hispanic | 19.5% |

| • Asian | 3% |

| • Others | 2.5% |

| Economics | |

| • Median income | ,907 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes |

11205, 11206, 11216, 11221, 11233, 11238

|

| Area code | 718, 347, 929, and 917 |

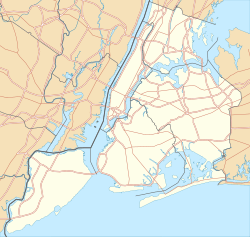

Bedford–Stuyvesant (often called Bed-Stuy) is a lively neighborhood in the northern part of Brooklyn, New York City. It's known for its beautiful old buildings and rich history. Bed-Stuy is surrounded by other Brooklyn neighborhoods like Williamsburg to the north and Crown Heights to the south.

This area is famous for having the largest collection of old Victorian buildings in the United States. Many of these homes are historic brownstones, built over 100 years ago. They have fancy details and classic designs.

Since the late 1930s, Bed-Stuy has been an important cultural hub for Brooklyn's African American community. Many African Americans moved here from Harlem because there was more housing available. In recent years, the neighborhood has seen many changes, with new people moving in and new shops and restaurants opening.

Bed-Stuy is mainly part of Brooklyn Community District 3. It is protected by the New York City Police Department and has several ZIP Codes.

History of Bedford–Stuyvesant

The name Bed-Stuy comes from two older areas: the Village of Bedford and Stuyvesant Heights. The name Stuyvesant honors Peter Stuyvesant, who was the last governor of the Dutch colony of New Netherland.

Early Days of Bed-Stuy

In the 1600s, the land that is now Bed-Stuy was owned by Dutch settlers. Bedford was an important settlement east of the village of Brooklyn. Stuyvesant Heights was mostly farmland back then.

In 1838, the Weeksville area within Bed-Stuy became one of the first free African American communities in the United States. This was a very important step for freedom and community building.

The hamlet of Bedford started when farmers wanted to improve their land. Governor Stuyvesant approved their request in 1663. Later, the British took over, but Bedford remained a recognized settlement.

Important roads met at Bedford Corners, which is now near Bedford Avenue and Fulton Street. These roads helped farmers bring their goods to market. A big part of the Battle of Long Island during the American Revolutionary War happened near this area.

Growing into an Urban Neighborhood

In 1800, Bedford became one of Brooklyn's seven districts. By 1834, it was part of the growing City of Brooklyn.

The streets we see today were planned in 1835. The old roads were replaced by a new street system. Many streets in Bed-Stuy are named after important figures in American history, like Francis Lewis (who signed the Declaration of Independence) and naval heroes like Bainbridge and Decatur.

In the 1870s, brick and stone row houses began to be built, changing the area from rural to urban. These homes were large and beautiful, with high ceilings and big windows. Wealthy families, like lawyers and merchants, moved into these houses. Bed-Stuy became known as a nice residential area, famous for its homes and churches.

The Capitoline Grounds, built in 1863, were once home to the Brooklyn Atlantics baseball team. In winter, they became an ice-skating rink! These grounds were removed in 1880.

By the late 1800s, with the arrival of electric trolleys and elevated trains, Bed-Stuy became a popular place for working-class and middle-class people who worked in downtown Brooklyn and Manhattan. Many older wooden homes were replaced with the brownstone rowhouses we see today.

Bed-Stuy in the 20th Century

In the early 1900s, the Williamsburg Bridge made it easier for people from the Lower East Side of Manhattan to move to Bed-Stuy.

During the 1930s and World War II, many African Americans moved to Bed-Stuy from the American South and the Caribbean. They found jobs at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. By 1950, over half of Bed-Stuy's population was African American.

In the 1950s, some real estate agents used unfair practices to encourage white families to move out, making it easier for poorer black families to move in. By 1960, most of the population was black.

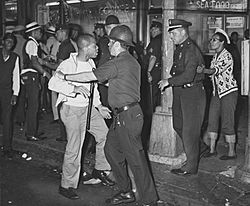

In the 1960s, there were some social challenges and tensions in the area. In 1964, there were some disturbances in the neighborhood.

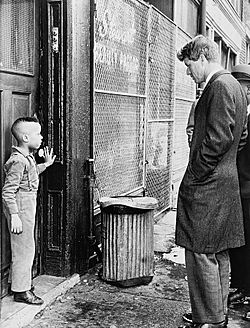

In 1967, Senator Robert F. Kennedy visited Bed-Stuy to understand the challenges facing the community. He helped create the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation (BSRC). This was the first community development organization in the United States. It aimed to help rebuild the neighborhood and create jobs. The BSRC bought and renovated homes, helped people buy houses, and even brought an IBM computer factory to the area.

In 1977, a citywide power outage affected New York City. Bed-Stuy and nearby Bushwick were heavily impacted, with many stores damaged.

Bed-Stuy Today

Since the early 2000s, Bed-Stuy has been changing. Many people are moving in because of the beautiful brownstone homes and safer streets. New shops, cafes, and restaurants have opened, making the neighborhood more diverse. This has led to some changes in who lives there and how much things cost.

Even during tough economic times, Bed-Stuy has continued to grow. More cafes, restaurants, and boutiques have opened, especially in the western and southern parts of the neighborhood. Many different kinds of people, like students, artists, and professionals, are moving to Bed-Stuy.

The community is working to improve the area, with new street trees, better sidewalks, and improved public transportation. High-speed internet services are also expanding. Local markets and food co-ops offer fresh and organic produce.

Parts of Bedford–Stuyvesant

Smaller Neighborhoods

- Bedford: This is the western part of Bed-Stuy. It was one of the first settlements east of Brooklyn village before the American Revolutionary War.

- Ocean Hill: Located in the eastern part, Ocean Hill got its name in 1890 because it has some small hills. For a long time, it was home to many Italian families. Later, it became a large African American community.

- Stuyvesant Heights: This is the central and northeast section. It has historically been a strong African American community.

- Weeksville: In the southeast, Weeksville was named after an ex-slave from Virginia. He bought land here in 1838 and started this community.

Historic Areas

|

Stuyvesant Heights Historic District

|

|

On Decatur Street

|

|

| Location | Roughly bounded by Macon, Tompkins, Decatur, Lewis, Chauncey, and Stuyvesant, New York, New York |

|---|---|

| Area | 42 acres (17 ha) |

| Built | 1870 |

| Architectural style | Italianate, Queen Anne, Romanesque |

| NRHP reference No. | 75001193 |

|

Stuyvesant Heights Historic District (Boundary Increase)

|

|

| Location | Roughly, Decatur St. from Tompkins to Lewis Aves., Brooklyn, New York |

| Area | 10 acres (4.0 ha) |

| Architect | multiple |

| Architectural style | Italianate, Second Empire, Queen Anne |

| NRHP reference No. | 96001355 |

| Added to NRHP | November 15, 1996 |

| Added to NRHP | December 4, 1975 |

The Stuyvesant Heights Historic District in Bed-Stuy is a special area with 577 old residential buildings. These homes were built between 1870 and 1900. They are mostly two- and three-story rowhouses. Important churches like the Our Lady of Victory Catholic Church and the Mount Lebanon Baptist Church are also in this district.

Several other historic districts have been recognized in the neighborhood. These areas help protect the unique architecture and history of Bed-Stuy.

People and Population

Bed-Stuy is home to about 152,403 people. Most residents are adults and young people. In 2016, the average household income was $51,907.

The population of Bed-Stuy has changed a lot over time. In the early 1900s, black families began to buy homes here. After a new subway line opened in 1936, many African Americans moved to Bed-Stuy from other crowded parts of the city. By 1961, it was even called "Little Harlem."

Between 1980 and 2015, the population grew by 34 percent. The neighborhood has become much more diverse. In 2000, most residents were black, but by 2015, the number of white and Hispanic residents had grown significantly. In 2019, the population was about 46% Black, 29% White, 20% Hispanic, and 3% Asian.

Safety and Services

The New York City Fire Department (FDNY) has seven fire stations in Bed-Stuy, helping to keep the community safe.

The United States Postal Service operates several post offices in and around Bed-Stuy, serving the different ZIP Codes in the area.

Learning and Libraries

Bed-Stuy has many schools. While some residents have college degrees, many are high school graduates. The good news is that more students in Bed-Stuy are doing well in reading and math.

Some public schools in the neighborhood are named after important African Americans. The main high school is Boys and Girls High School. Other schools include the Brooklyn Brownstone School and Paul Robeson High School for Business and Technology. There are also charter schools like Ember Charter School and Success Academy. The Brooklyn Waldorf School is another option.

The Brooklyn Public Library (BPL) has four branches in Bed-Stuy:

- The Bedford branch

- The Marcy branch

- The Macon branch, which is a historic Carnegie library and has a special collection about African American culture.

- The Saratoga branch, another Carnegie library.

Getting Around

Bed-Stuy has several ways to get around using public transportation. The New York City Subway serves the neighborhood with the IND Fulton Street Line (A and C trains) and the IND Crosstown Line (G train). The elevated BMT Jamaica Line (J, M, Z trains) also runs along the northern edge.

The Nostrand Avenue station of the Long Island Rail Road is also in Bed-Stuy.

Many bus routes run through the neighborhood, helping people travel north-south and east-west.

Famous People from Bed-Stuy

Many talented people have lived in or come from Bed-Stuy:

- Aaliyah (1979–2001), a Grammy-nominated singer.

- Big Daddy Kane (born 1968), a famous rapper.

- Shirley Chisholm (1924–2005), a pioneering congresswoman.

- Tommy Davis (1939–2022), a professional baseball player.

- Bobby Fischer (1943–2008), a World Chess Champion.

- Jackie Gleason (1916–87), a well-known actor and comedian.

- Lena Horne (1917–2010), a famous actress and singer.

- Jay-Z (born 1969), a hugely successful rapper and businessman.

- Norah Jones (born 1979), a popular singer.

- June Jordan (1936–2002), a poet and activist.

- Lil' Kim (born 1974), a rapper.

- Tracy Morgan (born 1968), a comedian and actor.

- Mos Def (aka Yasiin Bey) (born 1973), a rapper.

- The Notorious B.I.G. (1972–1997), a very influential rapper.

- Floyd Patterson (1935–2006), a famous boxer.

- Jackie Robinson (1919–1972), a legendary baseball player who broke barriers.

- Chris Rock (born 1965), a popular actor and comedian.

- Gabourey Sidibe (born 1983), an Academy Award-nominated actress.

- Mike Tyson (born 1966), a famous boxer.

Bed-Stuy in Movies and Music

Bed-Stuy has been featured in many popular culture works:

- The 1980 song "You May Be Right" by Billy Joel mentions walking through Bed-Stuy.

- The movie Do the Right Thing by Spike Lee is set in Bed-Stuy.

- Rapper Notorious B.I.G. often mentioned Bed-Stuy in his songs.

- The TV show Everybody Hates Chris is partly based in Bed-Stuy.

- The 2011 Jay-Z song "Gotta Have It" also mentions Bed-Stuy.

- The comic book series Hawkeye features Clint Barton living in an apartment in Bed-Stuy.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Bedford-Stuyvesant (Brooklyn) para niños

In Spanish: Bedford-Stuyvesant (Brooklyn) para niños