Benty Grange hanging bowl facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Benty Grange hanging bowl |

|

|---|---|

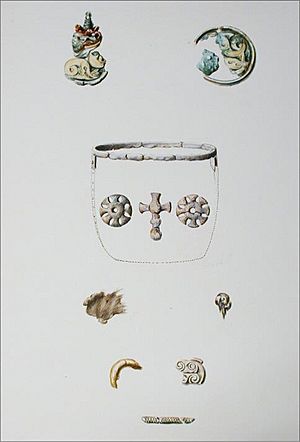

Reconstructed escutcheon design

|

|

| Material | Bronze, enamel |

| Discovered | 1848 Benty Grange farm, Monyash, Derbyshire, England 53°10′30″N 1°46′59″W / 53.174895°N 1.782923°W |

| Discovered by | Thomas Bateman |

| Present location | Weston Park Museum, Sheffield; Ashmolean Museum, Oxford |

| Registration | J93.1190; AN1893.276 |

The Benty Grange hanging bowl is an ancient object from the Anglo-Saxon period, around the 600s AD. Today, only two special bronze pieces called escutcheons remain. These are usually round, fancy decorations found on hanging bowls. A third piece broke apart soon after it was dug up.

These escutcheons were found in 1848 by a person who studied old things, Thomas Bateman. He was digging up an ancient burial mound, called a tumulus, at Benty Grange farm in Derbyshire, England. The escutcheons were definitely part of a complete hanging bowl when they were buried. The grave might have been robbed before Bateman found it. But it still held important items, showing it was a rich burial. These items included the hanging bowl pieces and a special Benty Grange helmet with a boar (wild pig) crest.

The escutcheons that are left are made of bronze with colourful enamel. They are about 40 mm (1.6 in) wide. Their design shows three creatures that look like dolphins arranged in a circle. Each one is biting the tail of the animal in front of it. The bodies of the animals and the background are made of enamel, probably all yellow. The outlines and eyes of the animals, and the edges of the escutcheons, were covered in a shiny silver-like metal.

One of the escutcheons is now owned by Museums Sheffield and is on display at the Weston Park Museum. The other is kept at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, but it is not currently on display.

Contents

What are Hanging Bowls?

Hanging bowls are thin bronze containers. They have three or four hooks around their rim, which were used to hang them up. These bowls are linked to Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Viking history and art. The hooks stick out from the escutcheons. These are bronze plates or frames, usually round or oval, and often decorated with fancy designs. Sometimes, there were also escutcheons at the bottom of the inside of the bowl.

In 2005, a list of hanging bowls found about 174 examples. Around 60 of these were mostly complete. Most were found in Britain and Ireland (141 bowls). Others were found in Norway (26) and other parts of Europe (7).

What were Hanging Bowls Used For?

We don't know exactly what hanging bowls were used for, or where they were first made. They seem to have been made by Celtic people. But they were still used during Anglo-Saxon and Viking times. People have suggested many ideas for their use. They might have been lamps or lamp reflectors. Perhaps they were used for religious purposes, like washing hands in churches. Some think they were for drinking, like the cups King Edwin of Northumbria supposedly left for travellers. They could also have been used for washing, or as special bowls in mead halls.

By the 600s, hanging bowls became a sign of wealth and importance. Owning one showed that you were a high-status person. Their role as a status symbol might have become more important than their original use.

What the Benty Grange Escutcheons Look Like

Only two escutcheons are left from the Benty Grange hanging bowl. They are made of enamelled bronze and are about 40 mm (1.6 in) across. They both have the same design and simple frames. Both escutcheons are broken, but enough remains to figure out their original design. We know they are two different pieces because their broken parts overlap.

It's not certain if they were hook escutcheons (from the rim) or basal escutcheons (from the bottom). But a ring on the back of one piece suggests it was connected to the hanging chains. A drawing from the time they were found also seems to show a hook. The enamel background looks yellow now, just as it did when it was found. Some people thought it might have been yellow creatures on a red background. But there isn't much proof for this.

The reconstructed design shows three "ribbon-style fish or dolphin-like creatures." Each one is biting the tail of the animal in front of it. Their bodies are outlined, and they don't have limbs. Their tails curl in a circle. Each animal has a small, pointed oval eye. The outer edges of the escutcheons, their plain frames, and the outlines and eyes of the animals were all covered in a shiny silver-like metal.

Records of the third escutcheon show it was different. Drawings show it had a swirling pattern and was about half the size of the other two. It might have been placed at the bottom of the hanging bowl. Nothing else from the bowl survived. Some old chain pieces were found nearby, but they were probably too heavy to have hung the bowl.

Similar Designs

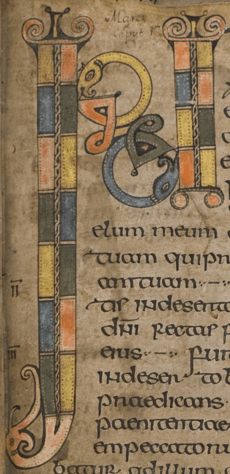

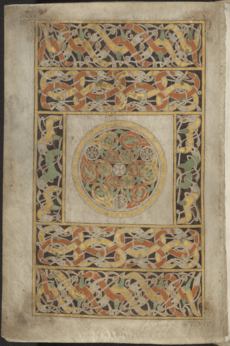

The animal designs on the Benty Grange hanging bowl are similar to designs on other escutcheons. But they are even more like designs found in old medieval illuminated manuscripts (fancy handwritten books). For example, three escutcheons from a hanging bowl found in Faversham also show dolphin-like animals.

However, several manuscript illustrations are even more similar to the Benty Grange designs. As early as 1861, Thomas Bateman noticed this. He pointed out that similar patterns were used in "several manuscripts of the VIIth Century" to decorate the first letters of chapters. It's possible that Anglo-Saxon metalwork designs, like those on the Benty Grange escutcheons, inspired some of the art in these books.

For instance, the Durham Gospel Fragment, from the mid-600s, has two similar fish-like designs. They are part of the big "INI" monogram that starts the Gospel of Mark. The Book of Durrow also has a similar picture of linked yellow dolphin-like creatures.

When Was It Made?

The Benty Grange hanging bowl is usually thought to be from the second half of the seventh century (the late 600s). This date is based on its design and other items found in the burial mound. Since a helmet and a cup with silver crosses were found, it suggests the burial happened after Christianity officially came to Mercia in 655 AD.

The surviving escutcheons also point to a mid-seventh-century date. This is because they look like the pictures in the Durham Gospel Fragment and the Book of Durrow. The basal disc of the Winchester hanging bowl, which the third Benty Grange escutcheon resembles, is also from around the same time.

How It Was Found

Where It Was Found

The hanging bowl was found in a barrow (a burial mound) on the Benty Grange farm in Derbyshire. This area is now part of the Peak District National Park. Thomas Bateman, an archaeologist who led the dig, described Benty Grange as a "high and bleak situation." The barrow is still there today. It's in a noticeable spot near a main Roman road, now the A515. This location might have been chosen to show off the burial to people passing by. It might also have been placed to be seen with two other nearby ancient sites: Arbor Low stone circle and Gib Hill barrow.

In the 600s, the Peak District was a small area between the kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria. It was home to an Anglo-Saxon group called the Pecsæte. This area became part of the Mercian kingdom around the 700s. The rich burials at Benty Grange and other sites suggest that the Pecsæte might have had their own rulers before then. However, there are no written records to confirm this.

The Dig

Bateman dug up the barrow on May 3, 1848. He didn't mention it, but he probably wasn't the first person to dig there. The objects were found in two separate groups, about 6 ft (1.8 m) apart. Also, other items usually found with a helmet, like a sword and shield, were missing. This suggests the grave had been robbed before. Because the mound was so large, it might also have held two burials. Bateman might have only found one of them.

The barrow is a circular mound about 15 m (50 ft) wide and 0.6 m (2 ft) high. It has a ditch around it, about 1 m (3.3 ft) wide and 0.3 m (1 ft) deep. Outside the ditch are earthworks about 3 m (10 ft) wide and 0.2 m (0.66 ft) high. The whole structure is about 23 by 22 m (75 by 72 ft). Bateman thought a body once lay in the center. He described finding strands of hair, but these are now believed to be from a fur cloak or similar material.

The objects found were in two groups. One group was near where the "hair" was found. The other was about 6 ft (1.8 m) to the west. In the western area, Bateman found a "large mass of oxydized iron." When cleaned, this turned out to be a jumbled collection of chains, a six-pronged iron tool like a hayfork, and the Benty Grange helmet.

In the area of the "hair," Bateman found "a curious assemblage of ornaments." These were hard to remove from the hard earth. They included a cup, which he thought was leather but was probably wood. It was about 3 in (7.6 cm) wide at the mouth. Its rim had silver edges. Its surface was decorated with four wheel-shaped ornaments and two crosses made of thin silver. These were attached with silver pins. He also found "a knot of very fine wire" and some "thin bone" decorated with patterns. This bone was attached to silk but quickly fell apart when exposed to air. The Benty Grange hanging bowl pieces were also found here. Bateman described them:

The other articles found in the same situation are principally personal ornaments, of the same scroll pattern as those figured at page 25 of the Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire;—of these enamels, there were two upon copper, with silver frames; and another of some composition which fell to dust almost immediately: the prevailing colour in all is yellow.

Bateman noted that the soil was "particularly corrosive." This meant it caused things to rust and decay quickly. He thought this was because the soil was mixed with a "corrosive liquid." This caused thin, rusty veins in the earth and made most human remains disappear. Bateman's friend, Llewellynn Jewitt, an artist, often joined him on digs. Jewitt painted four watercolours of the finds. Parts of these were included in Bateman's 1848 report. Jewitt made more paintings for this dig than any other, showing how important they thought the Benty Grange barrow was.

The hanging bowl escutcheons became part of Bateman's large collection. On October 27, 1848, he told the British Archæological Association about his discoveries. In 1855, the finds from Benty Grange were listed in his collection catalogue. Bateman died at 39 in 1861. In 1876, his son, Thomas W. Bateman, loaned the collection to Sheffield. It was displayed at the Weston Park Museum until 1893. Then, the younger Bateman had to sell the collection. The city bought many objects found in Yorkshire, Derbyshire, and Staffordshire. This included the helmet, cup fittings, and one of the hanging bowl escutcheons. Other pieces were sold by Sotheby's. Later in 1893, the second escutcheon was given to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford by Sir John Evans. As of 2021, the escutcheons are still in these two museums.

The Benty Grange barrow was made a scheduled monument on October 23, 1970. This means it's a protected historical site. The official listing says that even though the center of the barrow has been partly dug up, it's mostly untouched. It still holds important archaeological remains. It also notes that more digging could reveal new information. The nearby farm was updated between 2012 and 2014. As of 2021, it is rented out as a holiday home.

Bateman published an article about the Benty Grange dig in October 1848. This was just five months after he dug up the barrow. It appeared in The Journal of the British Archaeological Association. The finds were also in his 1855 collection catalogue. Before he died, Bateman updated his 1848 report in his 1861 book, Ten Years' Digging in Celtic and Saxon Grave Hills. Llewellynn Jewitt also wrote about the finds, including the hanging bowl, in his 1870 book, Grave-mounds and their Contents.

The Benty Grange hanging bowl was one of the first to be discovered. In 1898, John Romilly Allen included it among 16 examples in the first English article to talk about hanging bowls as a special type of object. It was often mentioned in books and papers after that. Many experts made drawings to show what the escutcheons might have looked like. These included T. D. Kendrick (1932, 1938), Françoise Henry (1936), Audrey Ozanne (1962–1963), George Speake (1980), and Jane Brenan (1991). Rupert Bruce-Mitford studied the Benty Grange burial again in 1974. He published what he called a "definitive" (final and most accurate) reconstruction of the escutcheons in 1987. In his book from 2005, A Corpus of Late Celtic Hanging-Bowls, he added a full description of the hanging bowl and a colour reconstruction of the escutcheons.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |