Bolesław Prus facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Bolesław Prus

|

|

|---|---|

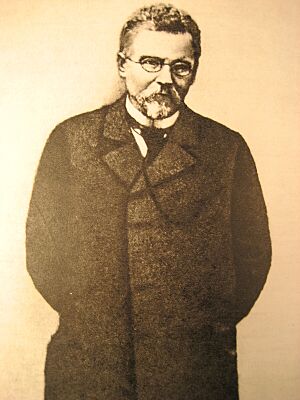

1887 photograph

|

|

| Born | Aleksander Głowacki 20 August 1847 Hrubieszów, Congress Poland |

| Died | 19 May 1912 (aged 64) Warsaw, Congress Poland |

| Pen name | Bolesław Prus |

| Occupation | Novelist, journalist, short-story writer |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Period | 1872–1912 |

| Genre |

|

| Literary movement | Positivism |

| Spouse | Oktawia Głowacka, née Trembińska |

| Children | Emil Trembiński (adopted) |

| Signature | |

Aleksander Głowacki (born August 20, 1847 – died May 19, 1912), known by his pen name Bolesław Prus, was a famous Polish writer. He was a leading figure in Polish literature and philosophy. His unique voice also made him important in world literature.

When he was 15, Aleksander Głowacki joined the Polish 1863 Uprising. This was a fight against the Russian Empire. Soon after his 16th birthday, he was badly hurt in battle. Five months later, he was put in prison for his part in the Uprising. These early experiences might have caused the anxiety he faced throughout his life. They also shaped his belief that Poland should not try to regain independence through fighting.

In 1872, at age 25, he started a 40-year career as a journalist in Warsaw. He wrote about science, technology, education, and how to improve society. These topics were very important for the Polish people. Poland had been divided by Russia, Prussia, and Austria in the 1700s. Głowacki chose his pen name "Prus" from his family's coat-of-arms.

Besides journalism, he wrote short stories. When these became popular, he started writing longer novels. Between 1884 and 1895, he wrote four major novels: The Outpost, The Doll, The New Woman, and Pharaoh. The Doll is about a man who is frustrated by his country's slow progress. Pharaoh is Prus's only historical novel. It explores political power and the fate of nations. This story is set in ancient Egypt during the fall of the 20th Dynasty.

Contents

Early Life and Challenges

Aleksander Głowacki was born on August 20, 1847, in Hrubieszów, Poland. This town was then part of the Russian-controlled area of Poland. His mother died when he was three years old. He was cared for by his grandmother and then his aunt. In 1856, when he was nine, his father died, and he became an orphan. He then went to a primary school in Lublin.

In 1862, his older brother Leon took him to Siedlce and then Kielce. Soon after, the Polish January Uprising began. Fifteen-year-old Prus ran away from school to join the rebels. His brother Leon was one of the leaders.

On September 1, 1863, Prus fought against Russian forces. He was injured and captured. This experience may have led to his lifelong agoraphobia, a type of anxiety. Five months later, he was arrested and imprisoned at Lublin Castle. He was released in May 1864 and lived with a relative.

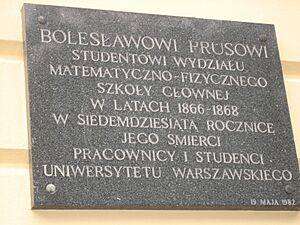

Prus finished secondary school in 1866. He then started studying mathematics and physics at Warsaw University. But he had to stop in 1868 because he was poor. In 1869, he tried studying forestry in Puławy. He was expelled after only three months. After that, he taught himself and worked as a tutor to support himself.

Journalism and Writing

In 1872, Prus started his career as a newspaper writer. He also worked for a short time at a machine factory in Warsaw. In 1873, he gave two public talks. These talks showed his wide interest in science.

As a newspaper writer, Prus wrote about many things. He talked about scientists like Charles Darwin. He urged Poles to study science and technology. He also encouraged them to develop industry and trade. He believed in helping those in need. His "Weekly Chronicles" columns lasted for forty years. They helped prepare Poland for its future growth in science and math. Prus believed that for Poland to thrive, it needed to be a useful part of civilization.

One thinker who greatly influenced Prus was Herbert Spencer. Spencer was an English sociologist who came up with the phrase "survival of the fittest." Prus saw Spencer as a very important thinker. He believed that "survival of the fittest" in society meant both competition and cooperation. He used Spencer's idea of society as a living organism in his stories.

In 1875, Prus married Oktawia Trembińska, a distant cousin. They adopted a boy named Emil. Emil was the model for a character in Prus's novel Pharaoh. Emil died at age seventeen.

Prus was a talented writer, known for his humor. He first used the pen name "Prus" for his newspaper columns and stories. He saved his real name, Aleksander Głowacki, for more serious writing.

In 1882, Prus became the editor of the Warsaw daily newspaper Nowiny (News). He wanted to make it a tool for improving his country. But the newspaper closed after less than a year. Prus then went back to writing columns. He continued working as a journalist even after becoming a successful novelist.

Prus also thought about the future. In 1884, he wrote about flying machines. He wondered if they would bring peace or more conflict. In 1909, he discussed H.G. Wells's prediction of a European Union. Wells thought it would include Western Slavs like Poles, Czechs, and Slovaks by the year 2000. This actually happened in 2004.

Famous Novels

Prus believed that literature, like science, could help us understand reality. He focused more on writing short stories. His stories were very popular. They showed his sharp eye for everyday life and his sense of humor. These stories often appeared in humor magazines.

Prus did not write historical fiction for a long time. He thought it would always twist history. But in 1888, he wrote his first historical story, "A Legend of Old Egypt." This story later became a starting point for his only historical novel, Pharaoh (1895).

Prus wrote four main novels about "great questions of our age":

- The Outpost (1886): About Polish peasants.

- The Doll (1889): About the rich and city people, and those trying to make society better.

- The New Woman (1893): About women's rights.

- Pharaoh (1895): About how political power works.

Pharaoh is considered his most far-reaching and popular work. Like his stories, Prus's novels were first published in parts in newspapers.

After selling Pharaoh, Prus traveled abroad in 1895. He visited cities like Berlin and Paris. In Paris, his agoraphobia prevented him from crossing the Seine River. But he was happy to see that his descriptions of Paris in The Doll were accurate. He had based them on books. After his trip, he returned home to recover. This was his last trip abroad.

Later Years and Legacy

Prus supported many good causes. But he later regretted taking part in welcoming Russia's tsar Nicholas II to Warsaw in 1897. Prus usually did not join political parties. He wanted to keep his journalistic fairness.

The terrible January Uprising of 1863 made Prus believe that society should improve through learning and hard work, not through risky fights. However, in 1905, Russia was defeated in the Russo-Japanese War. Poles then demanded more freedom. Prus changed his mind. He wrote an article saying, "with the greatest pleasure, I admit it—I was wrong!"

In 1908, Prus published Dzieci (Children), a novel about young revolutionaries. Three years later, he started his last novel, Przemiany (Changes). But he died before finishing it. These two later novels are not as famous as his earlier works.

Prus's last popular novel was Pharaoh, finished in 1895. It showed the end of ancient Egypt's Twentieth Dynasty. It also reflected Poland's loss of independence a century earlier. Prus did not live to see Poland regain its independence after World War I.

On May 19, 1912, Bolesław Prus died in his Warsaw apartment. He was 64 years old.

Thousands of people attended his funeral. He was buried at Powązki Cemetery. His tomb was designed by his nephew, Stanisław Jackowski. It has his name, his pen name, and the words "Heart of Hearts." Below the words is a statue of a little girl hugging the tomb. This shows Prus's love for children.

Prus's widow, Oktawia, lived for 24 more years. In 1902, a newspaper editor said that if Prus's writings were known worldwide, he should have received a Nobel Prize.

Lasting Impact

In 1961, a museum dedicated to Prus opened in Nałęczów, Poland. Prus vacationed there for 30 years. There are also sculptures of him there. He helped the young writer Stefan Żeromski with his career.

Prus believed in a realistic way of writing. But much of his work also had qualities of earlier Polish Romantic literature. He admired the Romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz. Prus's novels, especially The Doll and Pharaoh, helped shape the Polish novel of the 20th century.

The Doll is considered a great Polish novel. It has rich details and simple language. Joseph Conrad enjoyed Prus's work. He even said The New Woman was "better than Dickens."

Pharaoh, which explores political power, was a favorite of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. It is often called Prus's "best-composed novel." This is partly because it was finished before being published in parts.

The Doll and Pharaoh have been translated into many languages. The Doll has been made into films and a TV show. Pharaoh was made into a movie in 1966.

Prus also wrote about ethical ideas in his work The Most General Life Ideals (1905). He explored ideas about happiness and how society should work.

Prus's contributions to Polish literature and culture have been honored for many years. His 50th birthday was celebrated with special newspaper issues. A portrait of him was painted.

His birthplace, Hrubieszów, has a sculpture of him. A plaque at Warsaw University remembers his time there. In Holy Cross Church, Warsaw, a plaque by his nephew honors him as a "great writer and teacher of the nation."

His last home in Warsaw has a plaque. A street in Warsaw is named after him. A statue of Prus stands in a park in Warsaw.

A Polish cargo ship was named after him. From 1975 to 1984, his profile was on a 10-zloty coin. In 2012, new coins were made to mark 100 years since his death.

Prus's writings are still important today.

Works

Here is a list of important works by Bolesław Prus.

Novels

- Souls in Bondage (Dusze w niewoli, 1877)

- The Outpost (Placówka, 1885–86)

- The Doll (Lalka, 1887–89)

- The New Woman (Emancypantki, 1890–93)

- Pharaoh (Faraon, 1895)

- Children (Dzieci, 1908)

- Changes (Przemiany, begun 1911–12; unfinished)

Stories

- "Granny's Troubles" ("Kłopoty babuni," 1874)

- "The Palace and the Hovel" ("Pałac i rudera," 1875)

- "The Ball Gown" ("Sukienka balowa," 1876)

- "The Honeymoon" ("Miesiąc nektarowy", 1876)

- "Christmas Eve" ("Na gwiazdkę", 1877)

- "Little Stan's Adventure" ("Przygoda Stasia," 1879)

- "The Returning Wave" ("Powracająca fala," 1880)

- "Antek" (1880)

- "The Barrel Organ" ("Katarynka," 1880)

- "The Waistcoat" ("Kamizelka," 1882)

- "Fading Voices" ("Milknące głosy," 1883)

- "Mold of the Earth" ("Pleśń świata," 1884: a short story comparing human history to mold colonies)

- "The Living Telegraph" ("Żywy telegraf," 1884)

- "A Legend of Old Egypt" ("Z legend dawnego Egiptu," 1888: Prus's first historical fiction)

Nonfiction

- "Letters from the Old Camp" ("Listy ze starego obozu"), 1872: Prus's first writing signed with his pen name.

- "On the Structure of the Universe" ("O budowie wszechświata"), 1873.

- "On Discoveries and Inventions" ("O odkryciach i wynalazkach"), 1873.

- "Travel Notes (Wieliczka)" ["Kartki z podróży (Wieliczka)," 1878: Prus's thoughts on the Wieliczka Salt Mine.]

- "A Word to the Public" ("Słówko do publiczności," 1882: Prus's speech as editor of Nowiny).

- "The Paris Tower" ("Wieża paryska," 1887: about the Eiffel Tower before it was built).

- "Travels on Earth and in Heaven" ("Wędrówka po ziemi i niebie," 1887: Prus's thoughts on a solar eclipse.)

- The Most General Life Ideals (Najogólniejsze ideały życiowe, 1905: Prus's ideas on ethics).

- "Ode to Youth" ("Oda do młodości," 1905: Prus's change of mind about revolution).

- "Visions of the Future" ("Wizje przyszłości," 1909: a discussion of H.G. Wells's predictions).

Translations

Prus's books have been translated into many languages. His historical novel Pharaoh has been translated into twenty languages. His novel The Doll has been translated into at least sixteen languages.

Film Versions

- 1966: Faraon (Pharaoh), based on the novel Pharaoh.

- 1968: Lalka (The Doll), based on the novel The Doll.

- 1977: Lalka (TV serial, The Doll), a TV series based on The Doll.

- 1979: Placówka (The Outpost), based on the novel The Outpost.

- 1982: Pensja pani Latter (Mrs. Latter's Boarding School), based on the novel The New Woman.

Images for kids

-

"2012: Year of Prus": poster commemorating 100th anniversary of Prus's death, in a window of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Krakowskie Przedmieście, Warsaw, 2012

See also

In Spanish: Bolesław Prus para niños

In Spanish: Bolesław Prus para niños

- Flash fiction

- History of philosophy in Poland

- List of newspaper columnists

- List of Poles—Prose literature

- Positivism in Poland