Charles De Geer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles De Geer

|

|

|---|---|

Charles De Geer, painting by Gustaf Lundberg

|

|

| Born | 30 January 1720 Finspång, Sweden

|

| Died | 7 March 1778 (aged 58) Stockholm, Sweden

|

| Alma mater | Utrecht University |

| Known for | Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire des insectes, 8 vols. |

| Awards | Knight, Order of the Polar Star (1761) Commander Grand Cross, Order of Vasa (1772) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Entomology |

| Author abbrev. (zoology) | de Geer, De Geer |

Charles De Geer (born January 30, 1720 – died March 7, 1778) was a Swedish scientist who studied insects. He was also a successful businessman and loved collecting books. Charles came from a well-known Swedish-Dutch family. He was born in Sweden but spent most of his childhood in the Dutch Republic (modern-day Netherlands).

When he was 18, Charles moved back to Sweden. He then took charge of the ironworks at Lövstabruk. He became a very successful businessman and one of the richest people in Sweden. His company employed about 3,000 people. He also had a good career in public service. He became a high-ranking official at the royal court and was made a baron in 1773.

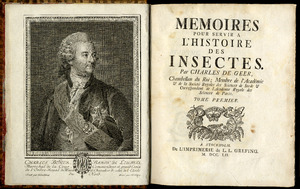

From a young age, Charles De Geer was very interested in natural history, especially insects. After returning to Sweden, this interest became a serious scientific pursuit. He joined the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1739. In 1748, he became a member of the French Academy of Sciences. His most important work was Mémoires pour servir de l'histoire des insectes. This book, written in French, had eight volumes published between 1752 and 1778. In it, he described the behavior of over 1,400 different insect species.

De Geer was also a passionate book collector. He used his large library for his scientific research. However, it also contained books on many other topics and in several languages. His collection included rare and beautiful books, even music scores. This showed his high social status as an aristocratic collector. Since 1986, his library has been part of Uppsala University Library. Most of the books are still kept in their original building at Lövstabruk.

Contents

Who Was Charles De Geer's Family?

Charles De Geer's father was Jean Jacques De Geer, and his mother was Jacquelina Kornelia van Assendelf. His mother was Dutch. Charles was part of the famous Swedish-Dutch De Geer family. His great-grandfather, Louis De Geer, started the Swedish branch of the family.

In 1743, Charles married Catharina Charlotta Ribbing. Charles De Geer was the first in his family to marry a Swedish woman. His wife came from a noble family, which brought Charles closer to the royal family. Unusually for their time, his wife made sure all their children were vaccinated against smallpox. She even received a medal for this important act. The couple had eight children. Their son, also named Charles De Geer, became a politician. Their daughter, Hedvig Ulrika De Geer, was also an intellectual and loved books, just like her father.

The family name is spelled with a capital "De." Charles De Geer himself always wrote "De" as part of his name. People sometimes called him "Charles the Entomologist." This helped tell him apart from other relatives with the same name.

Charles De Geer's Life Story

Growing Up in the Netherlands

Charles De Geer was born in Finspång, Sweden. But he moved to the Dutch Republic when he was only three years old. His family owned a large estate called Kasteel Rijnhuizen near Utrecht. His interest in nature began when he was living there. One story says his fascination started when he received silkworms. He loved watching them change into moths. By age sixteen, he had already organized his family's garden. He also kept pigeons and collected insects and butterflies.

Because his family was wealthy, he had private tutors. These included Dutch physicist Pieter van Musschenbroek and Swedish astronomer Olof Hiorter. Charles stayed in touch with Musschenbroek throughout his life. Musschenbroek's brother even built a microscope and other scientific tools for young Charles. Charles started studying at Utrecht University in 1738.

Charles grew up speaking Dutch. His travel diary from his move to Sweden in 1738 was written in Dutch. His first library catalog in Sweden was also in Dutch. But his second catalog, from around 1750, was in Swedish. After moving back to Sweden, he worked hard to learn Swedish. He spent some years in Uppsala to practice. Soon, he spoke Swedish very well. Less than a year after arriving, he wrote to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Swedish. He even apologized for any spelling mistakes, though they were very few.

Taking Over the Lövstabruk Ironworks

When Charles De Geer was ten, he inherited the Lövstabruk estate in northern Uppland, Sweden. An uncle, also named Charles, left him all his property. Charles didn't get control of the estate right away because he was so young. His father managed it, with help from Charles's older brother, Louis. Charles's father also worked to get investments from the Netherlands, where loans were cheaper.

Lövstabruk was an iron works, not just a farm. It was part of a group of ironworks in northern Uppland. Many Walloon immigrants from Belgium worked there. Charles De Geer's great-grandfather, Louis De Geer, developed it into an early industrial center. In the 1700s, it was Sweden's most important ironworks. When Charles took over, it employed over 3,000 people.

However, the estate was in financial trouble. Russian troops had burned Lövstabruk in 1719 during a war. The estate had not fully recovered. The owner at the time even thought about giving up and moving back to the Netherlands.

In the following years, Charles's father and older brother helped the estate recover. In 1738, his father died, and Charles moved to Lövstabruk. He formally took ownership at age 25. But he started managing the estate in 1741 and continued until his death. He was very involved in running the business, even with skilled staff helping him.

He became a very successful businessman and one of the richest people in Sweden. He greatly expanded the estate. He bought more woodlands to supply fuel for the ironworks. He also bought other ironworks to reduce competition. He sold some estates his family had bought, like Österbybruk, making a lot of money. Charles left instructions for his successor. He advised them to trust administrators carefully, not to worry too much about small details, to have good relations with the church and the king, and to treat workers well.

Improving Lövstabruk and Collecting Books

After Lövstabruk was burned in 1719, a new main building was built in the 1720s. When Charles De Geer took over, he made it bigger and better. He hired architect Jean Eric Rehn. Two wings were added to the main building. An aviary (a large birdcage) was built in the park in 1759. In 1765, the inside of the main building was also updated.

Two special pavilions were built next to the main building. One held his main library. The other housed his natural history collection, his working library, and his study.

Charles De Geer loved collecting books. Even with his business success, he is often remembered more for his library and scientific work. He started collecting books as a boy in the Netherlands. A letter from his father in 1736 described him as "a young man with a childlike fascination for nature and the reference library of an established scientist." By age twelve, he already owned books by famous naturalists. When he moved to Sweden in 1738, his books and scientific tools filled twelve wooden chests. This was not a typical collection for a teenager. It was a carefully chosen collection of handbooks, classic literature, and scientific works.

Once in Sweden, he kept buying books. He bought many science books from Olof Rudbeck the Younger, whom he met in Uppsala. He bought even more when Rudbeck's library was sold after his death in 1741. These included "marvellous" books on plants and animals. They helped make his library famous, even internationally. He bought books from Swedish sellers. But from 1746, most purchases were made by the Luchtmans bookdealers in Leiden, Netherlands. De Geer's strong connections with the Dutch book market showed how global trade affected even small villages far from big cities.

About a quarter of his books were on natural history, especially entomology (insects). His library had many standard works on biology and zoology of his time. It was clearly a research library. De Geer's insect books often mentioned books from his own library. But he also bought books on religion, philosophy, law, history, languages, travel, biographies, and fiction.

His library also had a collection of musical scores. This collection, now in Uppsala, is one of the finest from the 1700s in Sweden. It has about 90 printed albums and 37 handwritten music manuscripts. It includes music by famous composers like George Frideric Handel and Antonio Vivaldi. It also has music by Swedish composers like Francesco Uttini and Johan Helmich Roman. Some of these works are not found in any other library. Charles De Geer's library helped raise his status as a noble collector. His private collection, along with his natural history items, was probably only smaller than Count Carl Gustaf Tessin's collection in Sweden at that time.

Charles De Geer's library has about 8,500 books (including some added by later family members). Most are still in their original place. Most books are in French, but there are also books in Swedish, Latin, German, Dutch, and other languages. In 1986, Uppsala University Library bought the library. This was to prevent the collection from being sold and scattered. So, it remains "a kind of time capsule from the 1700s." Small items like playing cards and handwritten notes have been found between the pages. The library also has a celestial (stars) and a terrestrial globe (Earth) made by Anders Åkerman.

Charles De Geer's Scientific Work

Charles De Geer's early interest in natural history, especially insects, grew into full scientific work after he returned to Sweden. He likely attended lectures in Uppsala. He was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences at age 19 in 1739. The Academy hoped he would donate money. He never did, but he became an active member. He published his first scientific paper in 1740.

De Geer wrote several papers for the Academy's Transactions. One early paper from 1741 was about a type of spittlebug, Aphrophora salicis. He carefully observed and described the insect's life cycle. Earlier scholars believed spittlebugs were made from cuckoo spit. De Geer showed this was clearly false. In a speech in 1754, he strongly argued against the idea of spontaneous generation. He used many observations and facts to support his view. In 1748, De Geer became a member of the French Academy of Sciences.

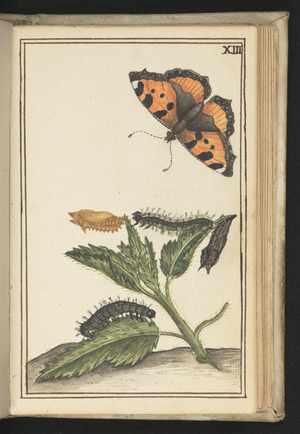

His most important scientific contribution was studying different insect species. He followed the methods of René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur. De Geer focused on insects that were considered pests or affected human activities. He made many careful observations of how over 1,400 insect species changed, ate, and reproduced. These observations were collected in his main work, Mémoires pour servir de l'histoire des insectes. It was published in French in eight volumes between 1752 and 1778. He edited the last volume while he was on his deathbed. De Geer seemed to see his work as a continuation of Réamur's book with the same title. This is why he also wrote it in French. Some people criticized it for being too similar to Réamur's work.

Still, it is one of the largest single works on zoology ever written by a Swede. It is considered a classic in insect literature. De Geer was a skilled artist. He drew all the illustrations himself, which were printed using 238 copper plates. A German translation was published between 1776 and 1782.

De Geer gave twelve copies of his book to Carl Linnaeus. He asked Linnaeus to give copies to any students interested in insects. Linnaeus gave one copy to Peter Forsskål. De Geer also sold some copies through the Luchtmans book traders in Leiden. These traders also supplied books for De Geer's library. Records show that copies of Mémoires were sold to famous scientists like Job Baster.

De Geer was probably the most important biologist in Sweden during the 1700s, after Linnaeus. He kept in touch with many other naturalists of his time. These included Charles Bonnet, Pierre Lyonnet, and Abraham Trembley. Linnaeus was a personal friend. Linnaeus often used De Geer's natural history collection. This collection included insects De Geer collected himself. It also had specimens he bought from other collectors. Among these were insects collected by Daniel Rolander in South America. Linnaeus referred to De Geer's collections over 50 times in his important book, the 10th edition of Systema Naturae. De Geer's collection is the only private collection (besides Carl Gustaf Tessin's) that Linnaeus listed as a separate source. However, De Geer was slow to use Linnaeus's two-part naming system for species. He also paid little attention to how species were organized into groups.

Public Life and Later Years

Charles De Geer also took part in public life. He attended every session of the Riksdag of the Estates (Sweden's parliament) between 1751 and 1772. However, he didn't seem very interested in politics. He was present but didn't play an active role. He also held positions at the Royal Court. In 1740, he became a Chamberlain. In 1760, he became Marshal of the Court. Charles De Geer was made a baron in 1773. He also received two royal awards: Knight of the Order of the Polar Star in 1761 and Commander Grand Cross of the Order of Vasa in 1772.

Soon after turning 50, he became ill with gout. This illness led to his death in 1778. He died in Stockholm. He is buried with his wife in a chapel in Uppsala Cathedral. After he died, De Geer's widow donated his collections of insects and birds to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. These collections were later added to the Swedish Museum of Natural History.

Images for kids

-

Kasteel Rijnhuizen outside Utrecht, where Charles De Geer grew up.

-

Whooper swan, manuscript illustration from the Book of Birds (Fogelboken) by Olof Rudbeck the Younger and possibly made by him. Charles De Geer bought the book together with several others when the library of Rudbeck was sold at an auction in 1741.

-

The tomb of Charles De Geer in Uppsala Cathedral