Chelsea porcelain factory facts for kids

Chelsea porcelain was a special type of porcelain made by the Chelsea porcelain factory. This was the very first important factory in England to make porcelain! It started around 1743–1745 in Chelsea, which was a very fashionable area. The factory made porcelain independently until 1770. Then, it joined up with another famous factory called Derby porcelain.

Chelsea porcelain was always made from a material called soft-paste porcelain. The factory changed its recipes for the porcelain and its shiny outer layer (called glaze) several times. Their products were made for rich people who wanted fancy things. The factory was also close to a popular fun spot called Ranelagh Gardens.

Some of the very first pieces known are "goat and bee" cream jugs. These jugs have little goats sitting at the bottom. Some even have "Chelsea", "1745", and a triangle mark carved into them. Nicholas Sprimont, a silversmith from France, was the main boss from about 1750. Early plates and dishes made around 1750 looked a lot like porcelain from Meissen in Germany, or even like fancy silver items, such as salt shakers shaped like shells.

Chelsea was also famous for its small figures. Many of these were single standing figures, like those from the Cries of London series. These figures were often quite small, only about 2.5 to 3.5 inches tall. They were part of a group called "Chelsea Toys," which the factory was very well known for in the 1750s and 1760s. These "toys" were tiny items that often had metal parts. They could be used as small boxes for candy (called bonbonnières), scent bottles, needlecases, or even thimbles. Many had French sayings on them, usually about love, but sometimes spelled a bit wrong!

After about 1760, the factory started getting ideas more from Sèvres in France instead of Meissen. They made big sets of vases and detailed groups of figures, like couples sitting in front of a screen of flowering plants (called a bocage background). These pieces often sat on a fancy base with swirly Rococo designs. Like other English factories, Chelsea often sold its items at public auctions, usually once a year. Old copies of their sales catalogs from 1755, 1756, and 1761 help us learn a lot about what they made.

In 1770, William Duesbury, who owned the Derby porcelain factory, bought the Chelsea factory. For a while, it was hard to tell the difference between Chelsea and Derby porcelain. This time is called the "Chelsea-Derby period" and lasted until 1784. After that, the Chelsea factory was torn down. Its molds, designs, and many workers and artists moved to Derby.

Contents

How We Identify Chelsea Porcelain

The history of the Chelsea factory, before it joined Derby, can be split into four main time periods. These periods are named after the special marks found on the bottom of the porcelain pieces. However, the marks didn't always change exactly when the materials or styles did. Some pieces from all periods don't have any marks at all. Sometimes, pieces even have two different marks! There are also anchor marks in blue and brown, and a very rare "crown and trident" mark in blue, found on only about 20 pieces, thought to be from around 1749.

Even though most factory marks are on the bottom of pieces, the tiny Chelsea anchor marks are often "hidden in the most unexpected places." For example, on a group of Chinese musicians, a tiny red anchor mark can be seen on the raised base, near the woman's ankle.

Triangle Period (around 1743–1749)

The earliest Chelsea porcelain had a triangle mark carved into it. Most of these items were white and looked a lot like silver designs. The early porcelain was very clear, almost like milky-white glass. Later, it became harder and looked a bit colder. During this time, the factory started using a method called slipcasting (pouring liquid clay into molds) for figures, which became their usual way of making them.

Some of the most famous items from this time were white salt shakers shaped like crayfish. The Goat and Bee jugs, also based on silver designs, are perhaps the most well-known. Other factories, like Coalport porcelain, even made copies of these jugs much later. Sales stopped in March 1749, which is probably when Nicholas Sprimont took charge. The factory also moved a short distance within Chelsea.

Raised Anchor Period (1749–1752)

On January 9, 1750, Sprimont announced the factory was open again, with "a great Variety of Pieces for Ornament in a Taste entirely new." The new mark, a raised anchor, probably celebrated this new beginning. The factory was very close to the Thames River. An anchor is a symbol of hope and of Saint Nicolas of Myra, who is the patron saint of sailors. Sprimont might have been named after him.

The next six years were the most successful for the factory. During this time, they changed the porcelain and glaze to make a clear, white, slightly not-quite-see-through surface for painting. You can see the influence of Meissen porcelain in their classical figures, scenes with old ruins, and harbor views. They also copied pictures from Francis Barlow's book of Aesop's Fables. In 1751, Chelsea copied two sets of dishes from Meissen. They also made figures of birds and animals inspired by Meissen. Flowers and landscapes were copied from Vincennes (which soon moved to Sèvres). A set of bird figures was based on drawings from A Natural History of Uncommon Birds by George Edwards. The copies they used were probably not colored, so even though the shapes were right, the colors on the figures were often strange and not accurate.

Red Anchor Period (1752–1756)

Just like at Meissen and Chantilly earlier, Chelsea started making copies of Japanese porcelain in the Kakiemon style. These were popular from the late 1740s until about 1758. They copied both the European copies and original Japanese pieces.

Some tableware was decorated with bold and very accurate paintings of plants. These are called "botanical" pieces. They brought the style of large, hand-colored plant drawings from books onto porcelain. The factory was very close to the Chelsea Physic Garden (a famous garden started in 1673 and still there today). This garden might have inspired the artists or given them books to copy from. Some pieces were copied from books by Philip Miller, the garden's director, and Georg Dionysius Ehret. An advertisement in 1758 even offered plates "enamelled from the Hans Sloane's Plants" (Sloane had helped set up the garden).

These new designs had a lasting impact on porcelain, especially in Britain. Similar styles became popular again in the late 20th century, led by Portmeirion Pottery's "Botanic Garden" range, which started in 1972.

The small "Toys" became very popular in this period. They might have been copied from the "Girl-in-a Swing" factory, which was probably in St James's, an even fancier part of London. This factory was active from about 1751–1754 and seemed to have some connection to Chelsea. Another new idea was making tureens (large serving dishes) and other big items shaped like animals, birds, or plants.

One example of Chelsea copying Meissen very closely is the "Monkey Band" (called Affenkapelle in German). This was a group of ten monkey musicians and a larger, excited conductor, all dressed in fancy clothes of the time. These kinds of monkey scenes were popular in many types of art.

Gold Anchor Period (1756–1769)

During this time, the influence of Sèvres in France was very strong, and French style was becoming very popular. Many older types of items were still made, but the gold anchor period brought rich colored backgrounds, lots of gold decoration, and the lively, curvy Rococo style. Chelsea started copying the Sèvres Rococo style just as Sèvres itself was moving to simpler shapes. Chelsea's sets of vases became very large and detailed, sometimes with as many as seven pieces of different sizes. The porcelain now included bone ash, and they used a wider range of colors and lots of gilding (gold decoration). The glaze sometimes dripped or pooled, and it had a slight greenish tint.

In 1763, King George III and Queen Charlotte sent a large Chelsea dinner service to the queen's brother, Adolphus Frederick IV, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. Giving porcelain as diplomatic gifts was common for royal factories in Europe, but it was new for England. This service was praised by Horace Walpole, who said it cost £1,200. Most of it is now in the Royal Collection, which has 137 pieces.

East Asian styles, like Japanese Imari ware, came back in the red anchor period but were even more common with the gold anchor. These styles remained a favorite in England, especially with later Crown Derby porcelain, and versions are still made today. Some English experts even thought the first Chelsea versions were "much more beautiful than their plain originals."

It seems that not much porcelain was made from 1763, perhaps because Sprimont wanted to retire. A sale in 1763 included some molds and parts of the factory. No special sale was held again until 1769, when molds were offered again.

In August 1769, Sprimont, whose health was poor, sold the factory to a man named James Cox. Then, in February 1770, William Duesbury of Derby porcelain and his partner John Heath bought it. The factory kept working in Chelsea, but during this time, the Chelsea items looked exactly like Duesbury's Derby items. This period is usually called "Chelsea-Derby." The very last Chelsea sale happened at Christie's on February 14, 1770.

People Behind the Porcelain

Nicholas Sprimont (1716–1771), a silversmith from Belgium, was the main public face of the Chelsea factory. But other important people were involved, and we don't know exactly what everyone did. Charles Gouyn (before 1737–1782), another silversmith in London, also sold porcelain. He was involved in the early years, but his exact role isn't clear. Some think he helped with the technical side of making porcelain, or that he provided money and was a big buyer or seller of the items. By 1749 or 1750, Sprimont and Gouyn might have had a disagreement. Gouyn might have even started another factory called the "Girl-in-a-Swing" factory, or St James's factory, named after the fancy street where his shop was.

Any porcelain factory needed a special chemist, called an "arcanist," who could figure out the recipes for the porcelain clay, the glaze, and the colors, and how hot to fire them. It's not clear who this person was at Chelsea. A paper thought to be by Sprimont mentions having "a casual acquaintance with a chymist who had some knowledge that way," who encouraged him to start the factory. Gouyn is one idea; another is Thomas Bryand, who showed examples of porcelain to the Royal Society in 1743.

Sir Everard Fawkener, who was secretary to the king's third son, Prince William, Duke of Cumberland, made large payments to the factory from 1746 to 1748. It's not clear if this money was from the prince or Fawkener himself, or exactly how he was helping to fund the factory. Royal families often invested in porcelain factories in Europe, but this was new for England. A five-inch tall portrait head of the prince was made, which was unusual for Chelsea. In 1751, a letter said that Fawkener borrowed some Meissen pieces for Chelsea to copy, and was described as "concerned in the manufacture of China at Chelsea." The same writer added, "I find that the Duke is a great encourager of the Chelsea China." A worker at the factory believed that Fawkener and Cumberland were the first owners, and they paid Sprimont a guinea a day. Fawkener died in 1758, and Sprimont might have finally become the full owner then.

Sprimont is usually seen as the person who designed the shapes of the tableware, often using metal items as inspiration. We don't know many of the artists who worked there. The main person who sculpted the figures was Joseph Willems from Belgium. He was at Chelsea from about 1749 to 1766, when he left for another factory. The miniature painter Jefferyes Hamett O'Neale is thought to be the "Chelsea Fable Painter," though some disagree. He later signed pieces for Worcester porcelain, but probably worked in London.

The famous sculptor Louis-François Roubiliac, who was French but worked in London, was long thought to have designed many figures. These figures were marked with an "R." However, it now seems that this mark means something else, and Roubiliac probably only designed a few models at most. Sprimont was the godfather of one of Roubiliac's daughters. One Chelsea figure definitely based on Roubiliac's work is the lying-down portrait of the painter William Hogarth's pug dog named Trump. Roubiliac sculpted Trump in clay around 1741. The figure later appeared in Chelsea porcelain and then in Josiah Wedgwood's Black Basalt pottery after he bought a copy of the clay sculpture in 1774.

William Duesbury, who bought the factory in 1770, used to paint Chelsea and other porcelain at his own workshop in London. We know this from his account book from 1751 to 1753. However, we can't be sure which Chelsea pieces were painted by his workshop. His books show that he painted many bird figures.

Selling and Collecting Chelsea Porcelain

Chelsea porcelain, and other English porcelain, was often sold through "chinamen" (dealers) and "warehouses" in Central London. These places sold mainly to smaller dealers and shopkeepers, often from outside London, but also directly to customers. We don't know as much about Chelsea's selling methods as we do about another factory called Bow. But Gouyn's shop in St James was probably a place where Chelsea porcelain was sold, at least in the early days.

The yearly auctions were partly for the chinamen. Some groups of items were put together to give them a good stock to sell. The East India Company had been selling its shipments of East Asian porcelain at auction for many years. Chelsea porcelain even reached British America, but probably not many pieces were sent to other countries in Europe.

People started collecting early English porcelain soon after it was made, especially in the late 1800s, when prices went up steadily. However, in the 1900s, collectors' interests changed a lot. Pieces from later in the century became much cheaper (even when considering inflation) than they were a hundred years ago. But the very rare earliest pieces have become incredibly valuable. In 2003, a serving dish shaped like a hen and chickens sold for £223,650, which was a record for 18th-century English porcelain at auction. In 2018, a pair of serving dishes shaped like plaice fish from around 1755, from the collection of David Rockefeller, sold for $300,000. Both of these sales happened at Christie's auction house.

Images for kids

-

Goat-and-Bee Jug, c. 1745–1749, Birmingham Museum of Art

-

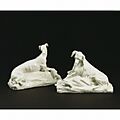

Pair of dogs, about 1749, 13.4 cm tall, V&A Museum

-

Pair of Hexagonal Vases in Kakiemon style, c. 1752–1755, Gardiner Museum, Toronto

-

Porcelain inkstand set, 1759–1769. The style and the "mazarine blue" color were copied from Sèvres. The Walters Art Museum.

-

The Four Elements set, 1760s

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |