Chicana feminism facts for kids

Chicana feminism is a special way of thinking and acting that looks closely at the history, culture, and challenges faced by Chicanas (Mexican American women) and the wider Chicana/o community in the United States. It helps women stand up against unfair rules in society. Anyone who fights to end unfair treatment of women in the community can be called a feminist.

Chicana feminism helped women find their voice during the Chicano Movement and the second-wave feminist movements in the 1960s and 1970s. Chicana feminists knew that helping women would help the whole Chicana/o community, even though they often faced resistance. New ideas, including from Chicana women who loved other women, helped broaden what it meant to be a Chicana.

Xicanisma is a new idea started by Ana Castillo in 1994. It aimed to refresh Chicana feminism and show how people's understanding had changed since the Chicano Movement. It also helped inspire the Xicanx identity. Chicana art, books, poems, music, and movies keep shaping Chicana feminism in new ways. Chicana feminism is often talked about with decolonial feminism, which means breaking free from old ways of thinking that came from colonization.

Contents

How it Started

Some Mexican American women were involved in the early fight for women's right to vote. In the early 1900s, this included women like Adelina Otero-Warren and Maria de G.E. Lopez. Otero-Warren came from a wealthy Hispano family. But most Mexican Americans, especially those with lower incomes and darker skin, lived in very different conditions.

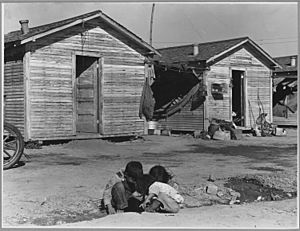

Before the late 1940s, Mexican American children often grew up in separate neighborhoods called colonias. These were often in company towns for farm workers. The U.S. government only allowed Mexican children, especially those with darker skin, to attend separate "Mexican schools." White schools taught subjects to prepare students for college. But at "Mexican schools," girls were only taught homemaking and sewing. Boys learned gardening and bootmaking. This kept people in certain social and income groups. Legal racial segregation ended in 1947 with Mendez v. Westminster. However, segregation still happened in many places because of racist attitudes.

Pachucas were young women in the 1940s who dressed in a unique style. They are sometimes seen as early feminists because they challenged traditional gender roles, especially during World War II. Pachucas are often not celebrated in Mexican American history. This is because they questioned the traditional role of women in the family. Pachucas sometimes carried things for self-defense. They were seen as "dangerously masculine" and "monstrously feminine."

Unlike women of color, white women usually did not have to deal with racism. White American women fought sexism in their communities through different waves of feminism. The first wave focused on women's suffrage (the right to vote). The second wave focused on issues like women's roles in public versus private life. However, women of color were mostly left out of these movements. This led Chicanas who were feminists to speak out. They criticized being excluded from both the main Chicano nationalist movement and the second-wave feminist movement. This is how Chicana feminism began in the 1960s.

Important Moments

Chicanas in the Chicano Movement (1960s–1970s)

The Chicano Movement aimed to empower the larger Mexican American community. But the stories and focus of the movement often ignored the women who helped organize it. During these events, Chicana feminists realized how important it was to connect issues of gender with the other goals of the Chicano Movement.

Chicanas also disagreed with the main second-wave feminist movement. They felt it did not include issues of racism and class differences in its goals. Chicanas felt left out of these mainstream feminist movements because they had different needs and demands. Through their constant protests, women went from being called Chicano women to Chicanas. They also pushed for using "a/o" or "o/a" to include both genders when talking about the community.

Alma Garcia wrote that the Chicana feminist movement was created to deal with the specific problems affecting Chicana women. It started because of how they were treated in the Chicano Movement and second-wave feminist movements. They wanted to be treated equally and with respect. The Chicana feminist movement encouraged many Chicanas to be more active. It helped them defend their rights not just as individuals, but as women working together for equal contributions in society.

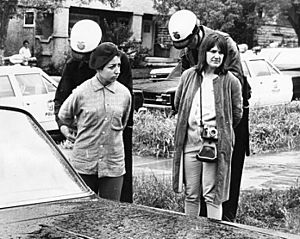

Chicana Walkout Organizing (1968)

On March 1, 1968, about 15,000 students took part in what became known as the East Los Angeles School Blowouts. Chicano students from seven high schools in East Los Angeles walked out of their schools together. Students organized because they were upset about racism, not enough money for schools, and the lack of Mexican history and culture in their lessons. Male students involved in the walkouts received most of the media attention. Thirteen male student organizers were even arrested.

A researcher named Dolores Delgado Bernal says that focusing only on male students made the role of girls and women seem much smaller. It also made their organizing efforts seem less important. Later, in the mid-1990s, Dolores Delgado Bernal interviewed eight important female leaders from the walkouts. She brought attention to the women the media had ignored. These women organized community meetings and connected students from different schools. They also published underground newspapers to spread the word and get more students to join.

National Chicana Conference (1971)

A year after the walkouts, the Chicano Youth Liberation Conference was held in 1969. About 1,500 Mexican American teenagers from across the country attended. This conference led to the ideas of "Chicanismo," "El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán," and the student group MEChA. At the conference, a workshop discussed the role of women. However, the workshop decided that "the Chicana woman does not want to be liberated." Many scholars believe this statement was a key reason that sparked the Chicana Feminist Movement.

After this, the first National Chicana Conference took place in Houston, Texas, in May 1971. Over 600 women from all over the United States came. They discussed issues like equal access to education, health and family planning, and creating childcare centers. The conference had nine different workshops.

Even though it was the first big meeting of its kind, the conference had many disagreements. Chicanas from different places and with different ideas argued about feminism's role in the Chicano movement. These arguments led to some women walking out on the last day. According to Anna Nieto-Gómez, the walkout showed the conflict between Chicana feminists and those who were loyal to the traditional Chicano movement.

Seen as Traitors to the Movement

Chicana feminists were often called "vendidas" (traitors) to the Chicano movement. This was called "vendida logic" by scholar Maylei Blackwell. They were accused of being against family, against men, and against the Chicano movement. Besides "vendida," Chicana feminists were also called "women's libber" or "agringadas" (acting like white Americans). Chicanas who put the Chicano movement first were known as Loyalists.

Women also worked to overcome inner struggles like self-hatred that came from the colonization of their people. This included breaking the mujer buena/mujer mala (good woman/bad woman) myth. In this myth, the traditional Spanish woman is seen as good, and the Indigenous woman is seen as bad. Chicana feminist ideas came about to challenge patriarchy (male dominance), racism, class differences, and colonialism. They also challenged how these oppressions became part of people's thinking.

Chicanas in the Family

Chicana feminists questioned their expected roles in la familia (the family). They demanded that their unique experiences, which combine different forms of unfairness, be recognized. Chicanas wanted to be aware, self-determined, and proud of their roots and heritage. They also wanted to prioritize La Raza (the people). As the Chicano Movement grew, the structure of Chicano families changed a lot. Women began to question the good and bad parts of the family dynamic and their place in the Chicano struggle.

Chicanas faced racism and unfairness from white America. But they also faced sexism within their own families. In her important book “La Chicana,” Elizabeth Martinez states: "The Chicana is oppressed by racism, imperialism (when one country controls another), and sexism. This is true for all non-white women in the United States. Her oppression by racism and imperialism is similar to what our men face. However, oppression by sexism is hers alone."

Chicana Labor Organizing

Emma Tenayuca was an early Mexican American labor organizer. Dolores Huerta was a major leader in organizing farmworkers.

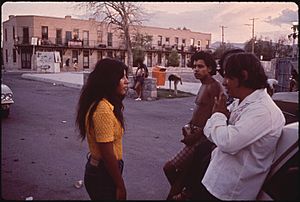

The Farah Strike, from 1972 to 1974, was called the "strike of the century." It was organized and led by Mexican American women, mostly in El Paso, Texas. Workers at the Farah Manufacturing Company went on strike. They fought for job security and their right to form a union.

Chicana Feminist Organizations (1960s–1970s)

One of the first Chicana organizations was the East Los Angeles Chicana Welfare Rights Organization. Alicia Escalante founded it in 1967. She became a strong voice for East Los Angeles at meetings where no one else from her neighborhood was present. She spoke out against the unfair treatment of people receiving welfare, especially Chicana and Black women. In a 1968 article for La Raza newspaper, she wrote that the state believed welfare recipients "should be ashamed of yourselves for living." She organized protests against cuts to welfare money for basic needs.

The Brown Berets were a youth group that took a more active approach to organizing for the Mexican-American community. They formed in California in the late 1960s. They valued strong bonds between women. They said women Berets must see other women in the group as hermanas en la lucha (sisters in the struggle). They encouraged them to stand together. Being a member of the Brown Berets helped Chicanas gain independence. It also gave them the ability to express their political views without fear. An important Chicana in the Brown Berets was Gloria Arellanes, the only female minister of the group.

The Hijas de Cuauhtémoc started as an activist rap group. By 1971, it became a feminist newspaper. It focused on Mexican feminism that would support people on both sides of the border. The newspaper covered topics like gender equality, relationships, women’s status, and leadership.

The Comisión Femenil Mexicana Nacional (CFMN) was founded in 1973. The idea for the CFMN came during the National Chicano Issues Conference. A group of Chicanas there noticed their concerns were not fully addressed. The women met outside the conference. They created a plan for the CFMN, establishing themselves as active and knowledgeable community leaders.

The Chicana Rights Project was created in 1974. It was a legal group for Chicana feminists. It aimed to defend the legal rights of Mexican American women. It dealt with issues of employment, health, education, and housing rights for Chicanas. It helped increase the number of Chicana women in programs in San Antonio. The organization ended in 1983.

Important Ideas (Late 1970s–1980s)

From the late 1970s to the early 1990s, Chicana feminism grew a lot. Many important books were written about Chicana lives and experiences. These books helped Chicanas develop a strong sense of self and understanding. Many of these works covered topics that had not been deeply explored before. These included gender roles, violence, and issues faced by queer people of color.

However, despite how important these books were, many were left out of discussions in Chicana/o studies for decades. They are still often ignored. This showed that the male-focused Chicanismo movement was slow to change its views. It did not give serious attention to Chicana ideas. Important books from this time that are key to Chicana/o studies, even if not always recognized, include:

- Diosa y Hembra: The History and Heritage of Chicanas in the U.S. (1976) by Martha P. Cotera

- The Chicana Feminist (1977) by Martha P. Cotera

- Essays on La Mujer (1977) edited by Rosaura Sánchez and Rosa Martinez Cruz

- Mexican Women in the United States (1980) by Magdalena Mora and Adelaida R. Del Castillo

- This Bridge Called My Back (1981) edited by Gloria Anzaldúa and Cherríe Moraga

- Loving in the War Years: Lo Que Nunca Pasó Por Sus Labios (1983) by Cherríe Moraga

- Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987) by Gloria Anzaldúa

- Companeras: Latina Lesbians (1987) edited by Juanita Ramos

- Chicana Lesbians: The Girls Our Mothers Warned Us About (1991) edited by Carla Trujillo

Xicanisma (1990s–Present)

Xicanisma is a new idea in Chicana feminism. Ana Castillo suggested it in her book Massacre of the Dreamers (1994). The letter X in Xicanisma refers to how Spanish colonizers could not say the "Sh" sound in Mesoamerican languages. So, they used the letter X in 16th-century Spanish. The X in Xicanisma points to this meeting between the Spanish and Indigenous peoples. It reclaims the X as a symbol of being at a crossroads or having a mixed identity.

This crossroads, or X, represents Indigenous survival after hundreds of years of colonization. It recognizes the moment "where the creative power of woman became deliberately taken over by male society." This happened when the coloniality of gender was forced upon women. Xicanisma talks about the need to reclaim Indigenous roots and spirituality. It also means bringing back the "forgotten feminine" that was put down by colonization. So, it challenges the male-focused parts of the movement and the male bias of the Spanish language. It is Xicanisma instead of Chicanismo.

Castillo argued that using this X as a symbol of a crossroads was important. She said, "language is the way we see ourselves in relation to the world." This means if we change the language we use to understand ourselves, we can change how we see and act in the world. The goal of Xicanisma for Castillo is not to replace male dominance with female dominance. Instead, it is to create "a society that is not focused on money or using others." In this society, "feminine principles of nurturing and community prevail." The feminine is brought back from its current lower position.

Main Ideas

Many main ideas of Chicana feminism have been developed by Chicanas. Chicana feminism shows a much bigger movement than people usually realize. It gives a platform to different minority groups to challenge those who oppress them. This includes racism, homophobia, and many other forms of social injustice. Chicana liberation frees individuals and the whole group. It allows them to live as they wish, demanding cultural respect and equality. Strength and overcoming challenges are key themes of Chicana feminism. It takes strength to not only divide but also create a new way of thinking about equality.

Female Archetypes

A key part of Chicana feminism is reclaiming the female figures of La Virgen de Guadalupe, La Llorona, and La Malinche. Changing the way these figures are traditionally seen (which is often male-dominated) to a decolonial feminist understanding is important. This is a crucial step for modern Chicana feminism. It helps reclaim Chicana female power and spirituality. Gloria Anzaldúa's important book Borderlands/La Frontera talks about the power of reclaiming Indigenous spirituality. This helps unlearn colonial and male-dominated ideas about women and motherhood. She writes: "I will no longer be made to feel ashamed of existing. I will have my voice: Indian, Spanish, white."

La Virgen de Guadalupe

La Virgen de Guadalupe, in the Catholic faith, has long been seen as a perfect example of female purity and motherhood. This is especially true in Mexican and Chicano culture. Members of the Chicana feminist movement, like artist Yolanda Lopez, wanted to reclaim the image of La Virgen. They wanted to break down the idea that virginity is the only way to measure a woman's worth. For women like Lopez, the image of Guadalupe had meaning that was not about religion at all.

The figure of La Virgen de Guadalupe is often compared to La Malinche. One is seen as a positive role model, the other as negative. These figures are historically and continuously held up to Mexican women and Chicanas. They are like mirrors for examining their own self-image and defining their self-esteem.

La Malinche

Malintzin (also known as Doña Marina by the Spanish) was born around 1505 to noble Indigenous parents in Mexico. Indigenous women were often used for political alliances at this time. Her mother and stepfather sold her into slavery to the Mayans to save her newborn brother's inheritance. Between the ages of 12 and 14, she was traded to Hernan Cortés as a servant. Because she was smart and spoke many languages, she became his "wife" and diplomat. She was Cortés's translator. She played a key role in the Spanish conquest of Tenochtitlan and the Aztec Empire. She had a son with Cortés, Martín, who is considered the first mestizo (person of mixed Indigenous and European descent).

After Mexico became independent from Spain in 1821, people needed someone to blame for centuries of colonial rule. Because of Malintzin's relationship with Cortés and her role as translator, she was seen as a traitor to her people. But Chicana feminism calls for a different understanding. Nationalism was not a concept known to Indigenous people in the 16th century. So, Malintzin could not have felt "Indian" or acted as a traitor on purpose. Malintzin was one of millions of women who were traded and sold in Mexico before colonization. With no way to escape, Malintzin showed loyalty to Cortés to survive.

Chicana feminism asks us to see her as someone who acted within her limited choices. She resisted torture (which was common) by becoming a partner and translator to Cortés. Blaming Malintzin for Mexico's conquest puts the responsibility on women to be the moral guides of society. It is important to understand Malintzin as a victim not of Cortés, but of myths. Chicana feminism says she should be praised for her ability to adapt and resist, which helped her survive.

By challenging traditional and colonial ideas, Chicana writers change their relationship to La Malinche and other powerful figures. They reclaim them to create a spirituality and identity that is both freeing from old ways and empowering. La Malinche is a victim of centuries of male-dominated myths that affect Mexican women's minds, often without them knowing.

Duality and "The New Mestiza"

The idea of "The New Mestiza" comes from feminist author Gloria Anzaldúa. In her book, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, she writes: "In a constant state of mental nepantilism, an Aztec word meaning torn between ways, la mestiza is a product of the transfer of the cultural and spiritual values of one group to another. Being tricultural, monolingual, bilingual or multilingual, speaking a mix of languages, and always changing, the mestiza faces the problem of the mixed person: which group does the daughter of a dark-skinned mother listen to? ...Inside us and inside Chicana culture, common beliefs of white culture attack common beliefs of Mexican culture, and both attack common beliefs of Indigenous culture. We feel attacked and try to fight back."

Anzaldúa offers a way of being for Chicanas that honors their unique perspective and experiences. This idea helps Chicanas who are always dealing with mixed identities and cultural clashes. It shows how they are always creating new knowledge and understanding themselves. This often involves understanding different types of unfairness. This idea shows that simply fighting back cannot be a way of life. This is because it depends on the dominant ideas of control, based on race, nationality, and culture. Fighting back locks one into a battle of oppressor and oppressed.

Just reacting means nothing new is being created or brought back in place of the dominant culture. It means the dominant culture must stay dominant for the fight to exist. For Anzaldúa, there must be space to create something new. "The new mestiza" was an important idea that changed what it meant to be Chicana. In this idea, being Chicana means having mixed identities, contradictions, being okay with uncertainty, and having many parts. Nothing is rejected from histories of unfairness. This idea also calls for combining all parts of identity and creating new meanings, not just balancing different parts.

Mujerista

The term mujerista was defined by Ada María Isasi-Díaz in 1996. It was greatly influenced by the "Womanist" approach of African American women, suggested by Alice Walker. This Latina feminist identity uses the main ideas of womanism. It fights inequality and unfairness by taking part in social justice movements within the Latina/o community. Mujerismo is based on relationships built with the community. It highlights individual experiences in relation to "community struggles" to redefine the Latina/o identity.

Mujerismo refers to the ideas and knowledge. Mujerista refers to the person who believes in these ideas. The origins of these terms began with Gloria Anzaldúa's This Bridge We Call Home (1987), Ana Castillo's Massacre of the Dreamer: Essays in Xicanisma (1994), and Gloria Anzaldúa and Cherríe Moraga's This Bridge Called My Back (1984). Mujerista is a Latina-focused "womanist" way of living and relating to others. It stresses the need to connect public life (work and education) with private life (culture and home). It values cultural experiences highly. It is different from Feminista, which focuses on the history of the feminist movement. To be Mujerista means to combine body, emotion, spirit, and community into one identity. Mujerismo recognizes that personal experiences are valuable sources of knowledge. All these parts together form a base for group action, like activism.

Nepantla Spirituality

Nepantla is a Nahua word that means "in the middle of it" or "middle." Nepantla can be described as a concept or way of thinking where many realities are experienced at the same time. As a Chicana, understanding and having Indigenous knowledge of spirituality is very important. It helps with healing, breaking free from colonial ideas, appreciating culture, and understanding and loving oneself. Nepantla is often linked to Chicana feminist author Gloria Anzaldúa. She created the term "Nepantlera." "Nepantleras are people who stand on the edge; they move within and among many, often conflicting, worlds. They refuse to fully side with any single person, group, or belief system." Nepantla is a way of being for the Chicana. It shapes how she experiences the world and different systems of unfairness.

Body Politics

Encarnación: Illness and Body Politics in Chicana Feminist Literature by Suzanne Bost talks about how Chicana feminism has changed how Chicana women view body politics. Feminism has moved beyond just looking at identity. It now looks at how "the connections between specific bodies, cultural settings, and political needs" work. It now looks beyond just race. It includes how movement, access, ability, and caregivers' roles in lives work with the bodies of Chicanas. Examples of Frida Kahlo and her abilities are discussed, as well as Gloria Anzaldúa's diabetes. This shows how ability must be talked about when discussing identity. Bost writes that "Since there is no single or constant place of identity, our analyses must adapt to different cultural frameworks, changing feelings, and things that are fluid. Our thinking about bodies, identities, and politics must keep moving." Bost uses examples of modern Chicana artists and literature to show this. Chicana feminism has not ended; it is just showing up in different ways now.

Queer Interventions

Chicana feminist ideas grew into a theory of the body and flesh. This was due to the important works of Gloria Anzaldúa and Cherrie Moraga. Both of them identify as queer (meaning they are not heterosexual). Queer ideas in Chicana feminist thought called for including and honoring the community's jotería (queer people). In La Conciencia de la Mestiza, Anzaldúa writes that "the mestizo and the queer exist at this time and point on the path of evolution for a purpose. We are a blend that proves all blood is closely connected and that we come from similar souls." This idea makes queerness a central part of freedom. It is a lived experience that cannot be ignored or left out.

In Queer Aztlán: the Reformation of Chicano Tribe, Cherríe Moraga questions how Chicano identity is built in relation to queerness. She criticizes how people of color are excluded from mainstream gay movements. She also points out the homophobia common in Chicano nationalist movements. Moraga also talks about Aztlán, the spiritual land and nation important to Chicano ideas. She discusses how the community needs to create new forms of culture to survive. "Feminist critics are committed to preserving Chicano culture. But we know that our culture will not survive marital assault, abuse, AIDS, and the pushing aside of lesbian daughters and gay sons." Moraga brings up criticisms of the Chicano Movement. She says it has ignored problems within the movement itself. These need to be addressed for the culture to be preserved.

Chicana Lesbian Feminism

In Chicana Lesbians: Fear and Loathing in the Chicano Community, Carla Trujillo discusses how being a Chicana lesbian is very hard. This is because of their culture's expectations about family and traditional male-female relationships. Chicana lesbians who become mothers challenge this expectation. They become free from the social norms of their culture. Trujillo argues that simply being a lesbian challenges the established norm of male-dominated unfairness. She argues that Chicana lesbians are seen as a threat. This is because they challenge a male-dominated Chicano movement. They raise awareness among many Chicana women about independence.

In 1991, Carla Trujillo edited and put together the book Chicana Lesbians: The Girls Our Mothers Warned Us About (1991). This book featured cover art by Ester Hernandez called "La Ofrenda." Vincent Carillo argued that the artwork challenged common ways of showing Chicanas and gender roles. This book included poems and essays by Chicana women. They created new understandings of themselves through their race.

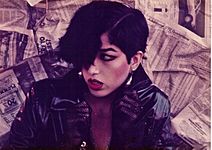

Chicana Art

Art gives Chicana women a way to express their unique challenges and experiences. Artists like Ester Hernandez and Judite Hernandez do this. During the Chicano Movement, Chicanas used art to show their political and social resistance. Through different art forms, both in the past and today, Chicana artists have continued to push the limits of traditional Mexican-American values. Chicana art uses many different ways to express feminist ideas. These include murals, paintings, and photography.

The energy from the Chicano Movement led to a cultural rebirth among Chicanas and Chicanos. Political art was created by poets, writers, and artists. It was used to fight against being treated as second-class citizens. In the 1970s, Chicana feminist artists worked differently from white feminist artists. Chicana feminist artists often worked together in groups that included men. White feminist artists usually worked only with other women. Through different art forms, both in the past and today, Chicana artists have continued to push the limits of traditional Mexican-American values.

Chicana Art Groups

Mujeres Muralistas

Mujeres Muralistas was a women's art group in the Mission District of San Francisco. Members included Patricia Rodriguez, Graciela Carrillo, Consuelo Mendez, Irene Perez, Susan Cervantes, Ester Hernandez, and Miriam Olivo.

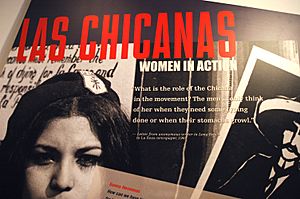

Las Chicanas

Las Chicanas had only women members. These included artists Judy Baca, Judithe Hernández, Olga Muñiz, and Josefina Quesada. In 1976, the group showed their art called Venas de la Mujer at the Woman's Building.

Los Four

Muralist Judithe Hernández joined this all-male art group in 1974 as its fifth member. The group already included Frank Romero, Beto de la Rocha, Gilbert Luján, and Carlos Almaráz. The group was active from the 1970s to the early 1980s.

Social Public Art Resource Center (SPARC)

In 1976, co-founders Judy Baca (the only Chicana), Christina Schlesinger, and Donna Deitch started SPARC. SPARC had studio and workshop spaces for artists. SPARC worked as an art gallery and also kept records of murals. Today, SPARC is still active. Like in the past, it encourages Chicana/o community members to work together on cultural and artistic projects.

The Woman's Building (1973-1991)

The Woman's Building opened in Los Angeles, CA, in 1973. It housed women-owned businesses and had many art galleries and studios. Women of color, including Chicanas, historically faced racism and unfair treatment there from white feminists. Not many Chicana artists were allowed to show their work there. Chicana artists Olivia Sanchez Brown and Rosalyn Mesquite were among the few included. Also, the group Las Chicanas showed Venas de la Mujer in 1976.

Murals

Murals were the favorite type of street art used by Chicana artists during the Chicano Movement. Judy Baca led the first big project for SPARC, The Great Wall of Los Angeles. It took five summers to complete the 700-meter-long mural. Baca, Judithe Hernández, Olga Muñiz, Isabel Castro, Yreina Cervántez, and Patssi Valdez completed the mural. Over 400 more artists and young community members also helped. The mural is in the Valley Glen area of the San Fernando Valley. It shows California's forgotten history of people of color and minorities.

In 1989, Yreina Cervántez and her assistants began the mural La Ofrenda. It is in downtown Los Angeles. The mural honors Latina/o farm workers. It features Dolores Huerta in the center with two women on either side. These women represent women's contributions to the United Farmer Workers Movement. La Ofrenda was considered historically important. In 2016, work began to restore La Ofrenda after graffiti and another mural were painted over it.

An exhibition featured previously mistreated or censored murals. It chose Barbara Carrasco's L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective. This mural started in 1981 and took about eight months to finish. It had 43 eight-foot panels that told the history of Los Angeles up to 1981. Carrasco researched the history of Los Angeles and met with historians as she planned the mural. The mural was stopped after Carrasco refused changes demanded by City Hall. This was because of her depictions of formerly enslaved businesswoman Biddy Mason, the internment of Japanese American citizens during World War II, and the 1943 Zoot Suit Riots.

Film

The short film Chicana, made in 1979 by Sylvia Morales, was added to the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress in 2021. The film was noted for its artistic way of making a documentary. It used a "mix of artworks, still images, documentary footage, narration, and personal stories" through a Chicana feminist lens.

Linda García Merchant is an Afro-Chicana filmmaker. She has made several films, including Las Mujeres de la Caucus Chicana, Palabras Dulces, Palabras Amargas, and the short film about her own life, No Es Facil.

Performance Art

Performance art was not as popular among Chicana artists, but it still had supporters. Patssi Valdez was a member of the performance group Asco from the early 1970s to the mid-1980s. Asco's art talked about the problems that come from Chicanas/os' unique experience. This experience is at the meeting point of racial and gender unfairness.

Photography

Laura Aguilar is known for her "caring photography." She often used herself as the subject of her work. She also photographed people who were not often seen in mainstream media: Chicanas, the LGBTQ community, and women of different body types. In the 1990s, Aguilar photographed the people at a lesbian bar in Eastside Los Angeles. Aguilar used her body in the desert as the subject of her photos. She made it look like it was sculpted from the landscape. In 1990, Aguilar created Three Eagles Flying. This was a three-panel photograph. She was in the center panel with the flags of Mexico and the United States on opposite sides. Her body was tied up by rope, and her face was covered. This artwork showed the feeling of being trapped by the two cultures she belonged to.

Archivists

In 2015, Guadalupe Rosales started an Instagram account that became Veterans and Rucas (@veterans_and_rucas). It began as a way for Rosales's family to connect over their shared culture by posting images of Chicana/o history. It soon grew into an archive dedicated to 90s Chicana/o youth culture and even as far back as the 1940s. Rosales has also created art installations to show the archive outside of its original digital format. She has had solo shows like Echoes of a Collective Memory and Legends Never Die, A Collective Memory.

The idea of sharing the forgotten history of Chicanas/os has been popular among Chicana artists since the 1970s. Judy Baca and Judithe Hernández have both used the theme of correcting history in their mural works. In modern art, Guadalupe Rosales uses the theme of collective memory to share Chicana/o history.

La Virgen

Yolanda López and Ester Hernandez are two Chicana feminist artists. They used new interpretations of La Virgen de Guadalupe to empower Chicanas. La Virgen is a symbol of the challenges Chicanas face. These challenges come from the unique unfairness they experience in religion, culture, and because of their gender.

- Ester Hernández refers to the sacred Virgen de Guadalupe in her painting, La Ofrenda (1988). This painting recognizes love between women and challenges the traditional role of la familia. It went against the holiness of La Virgen by showing her as a tattoo on a lesbian's back. La Virgen de Guadalupe Defendiendo los Derechos de Los Xicanos (1975)

- Alma Lopez – Our Lady of Controversy "Irreverent Apparition" (2001). This image uses mixed media and is a disrespectful depiction of La Virgen. See L.A. Times article

Chicana Literature

Since the 1970s, many Chicana writers (like Cherríe Moraga, Gloria Anzaldúa and Ana Castillo) have shared their own definitions of Chicana feminism through their books. Moraga and Anzaldúa edited a collection of writings by women of color called This Bridge Called My Back (published by Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press) in the early 1980s. Cherríe Moraga, along with Ana Castillo and Norma Alarcón, adapted this collection into a Spanish-language book called Esta Puente, Mi Espalda: Voces de Mujeres Tercermundistas en los Estados Unidos. Anzaldúa also published a bilingual (Spanish/English) collection, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. Mariana Roma-Carmona, Alma Gómez, and Cherríe Moraga published a collection of stories called Cuentos: Stories by Latinas. The Spanish language has been called a very important part of keeping Chicana culture alive.

The first Chicana Feminist Journal was published in 1973. It was called Encuentro Femenil: The First Chicana Feminist Journal. Anna Nieto-Gómez published it. One of the first Chicana novels about lesbians was Sheila Ortiz Taylor's Faultline, published in 1982.

Juanita Ramos and the Latina Lesbian History Project put together a collection. It included tatiana de la tierra's first published poem, "De ambiente," and many oral histories of Latina lesbians. This was called Compañeras: Latina Lesbians (1987).

Chicana feminist poet Gloria Anzaldúa points out that labeling a writer based on their social position helps readers understand the writer's place in society. However, while it is important to know a writer's identity, it does not always show in their writing. Anzaldúa notes that this type of labeling can push aside writers who do not fit into the main culture.

Since the 1990s, there has been more Chicana literature that includes transnational feminism and transcultural themes. This means it connects Chicana experiences with the wider Latin American context. For example, this is shown in Graciela Limón's books In Search of Bernabe (1997) and Erased Faces (2001).

Chicana Music

Chicana musical artists are often left out of Chicano music history. Many, like Rita Vidaurri and María de Luz Flores Aceves (known as Lucha Reyes), from the 1940s and 50s, helped advance Chicana Feminist movements. For example, Vidaurri and Aceves were among the first Mexican women to wear charro pants while performing rancheras (a type of Mexican music).

By challenging their own mixed backgrounds and ideas, Chicana musicians have continuously broken the gender norms of their culture. This has created a space for discussion and change in Latino communities.

There are many important figures in Chicana music history. Each one has given a new social identity to Chicanas through their music. An important example of a Chicana musician is Rosita Fernández, an artist from San Antonio, Texas. She was popular in the mid-20th century. Lady Bird Johnson called her "San Antonio's First Lady of Song." This Tejano singer is still a symbol of Chicana feminism for many Mexican Americans today. She was described as "larger than life." She often performed in china poblana dresses throughout her career, which lasted over 60 years. However, she never became very famous outside of San Antonio. This was despite her long time as one of the most active Mexican American women public performers of the 20th century.

Other Chicana musicians and musical groups:

- Chelo Silva – Tejana Singer

- Eva Ybarra – Tejana Accordionist (born 1945)

- Ventura Alonzo – Chicana Accordionist (1904–2000)

- Eva Garza – Tejana Singer

- Selena Quintanilla-Pérez – Tejana Singer (1971–1995)

- Girl in a Coma – Tejana indie rock band from San Antonio

- Quetzal – East Los Angeles Chicano alternative rock band

- Bags – Los Angeles punk rock band, led by Alice Bag.

Notable People

- Alma M. Garcia - Professor of Sociology at Santa Clara University.

- Ana Castillo - Writer, Novelist, Poet, Editor, Essayist and Playwright. She is known for showing the real experiences of Chicana feminism.

- Anna Nieto-Gómez – Key organizer of the Chicana Movement and founder of Hijas de Cuauhtémoc.

- Carla Trujillo - Writer, editor, and lecturer.

- Chela Sandoval – Associate Professor in the Chicano and Chicana Studies Department at University of California, Santa Barbara.

- Cherríe Moraga – Essayist, poet, activist educator, and artist at Stanford University.

- Dolores Huerta - Started the National Farm Worker's Association with César Chavez in 1962.

- Ester Hernandez - Uses art (like pastels, prints, and illustrations) to show the experiences of Latina and Native women.

- Gloria Anzaldúa – Scholar of Chicana cultural ideas and author of Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, among other important Chicana books.

- Judithe Hernandez - Los Angeles muralist who worked with Cesar Chavez to paint murals. These murals broke barriers to promote the Chicana movement.

- Martha Gonzalez (musician) - Chicana artist and activist. She is a co-leader of the Grammy-award-winning band Quetzal (band).

- Martha P. Cotera – Activist and writer during the Chicana Feminist Movement and the Chicano Civil Rights Movement.

- Norma Alarcón – Important Chicana feminist author.

- Sandra Cisneros – Key contributor to Chicana literature.

- Vicki L. Ruiz - American historian who focuses on Mexican-American women in the 20th century.

- Elizabeth Martinez - Longtime social justice activist and author.

Notable Organizations

- Alianza Hispano-Americana - Founded in 1894. Its members promoted good citizenship, provided social activities, and offered health benefits and insurance.

- Las Fotos Project – Helps Latina youth build self-esteem and confidence through photography and self-expression.

- National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) - A civil rights organization in the United States. It was formed in 1909 to advance justice for African Americans.

- National Chicano Youth Liberation Conference - Organized by the Crusade for Justice. This event came from El Plan Espiritual de Aztlan, which aimed to organize the Chicano people around a nationalist program.

- National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) - A federal agency founded by Congress in 1935. It protects employees' rights to organize and join unions to bargain with their employers.

- Ovarian Psycos - Young feminists of color in East Los Angeles who empower women through their bicycle brigades and rides.

- Radical Monarchs - A social justice group in California for young girls of color. They earn social justice badges. Influenced by Brown Berets and Black Panthers, these young girls want to create change in their communities.

See also

In Spanish: Feminismo chicano para niños

In Spanish: Feminismo chicano para niños

- Black feminism

- Chicano studies

- Feminism in Mexico

- Gender inequality in Mexico

- Gypsy feminism

- Intersectionality

- Third-world feminism

- White feminism

- Womanism

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |