Claude Nicolas Ledoux facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Claude-Nicolas Ledoux

|

|

|---|---|

Ledoux by Martin Drolling, 1790

|

|

| Born | 21 March 1736 Dormans-sur-Marne, France

|

| Died | November 18, 1806 (aged 70) Paris, France

|

| Occupation | Architect |

Claude-Nicolas Ledoux (born March 21, 1736 – died November 18, 1806) was an important French architect. He was one of the first to use the Neoclassical style in France. This style used ideas from ancient Greek and Roman buildings.

Ledoux was known for his big ideas. He designed not just buildings but also entire towns. His most famous idea was for an "Ideal City" called Chaux. Because of these grand plans, people sometimes called him a utopian architect. This means he dreamed of perfect places.

Many of his biggest projects were paid for by the French king. But because of this, his buildings became symbols of the old French government, called the Ancien Régime. When the French Revolution began, it stopped his career. Many of his works were later destroyed.

In 1804, Ledoux published a book of his designs. It was called L'Architecture considérée sous le rapport de l'art, des mœurs et de la législation. This means "Architecture considered in relation to art, morals, and law." In this book, he updated his old designs to fit the newer Neoclassical style.

His most ambitious project was the Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans. This was a huge salt factory that was also meant to be a visionary town. It showed many examples of architecture parlante, which means "speaking architecture." This is when a building's design tells you its purpose. Ledoux also designed everyday buildings, like about sixty fancy tollgates around Paris. These were part of the Wall of the General Tax Farm.

About Claude-Nicolas Ledoux

Ledoux was born in 1736 in Dormans, a small town in France. His father was a simple merchant. From a young age, his mother and godmother encouraged his drawing skills.

Later, a church group called the Abbey of Sassenage helped him study in Paris. He went to the Collège de Beauvais from 1749 to 1753. There, he studied Classics, which included ancient Greek and Roman history and literature.

When he was 17, he worked as an engraver. Four years later, he started studying architecture. His main teacher was Jacques-François Blondel, whom he respected throughout his life. He also learned from Pierre Contant d'Ivry and Jean-Michel Chevotet. These architects designed in both the fancy French Rococo style and an early Neoclassical style called "Goût grec" (Greek taste).

From his teachers, Ledoux also learned about Classical architecture. He was especially inspired by the ancient temples of Paestum in Italy. The works of Palladio, a famous Renaissance architect, also influenced him greatly.

Ledoux's teachers introduced him to rich clients. One of his first supporters was Baron Crozat de Thiers. He was a very wealthy art lover who asked Ledoux to redesign part of his grand house in Paris.

Early Buildings (1762–1770)

In 1762, young Ledoux got a job to redecorate the Café Godeau in Paris. He used clever painting tricks called trompe-l'œil and many mirrors. He painted fake columns on the walls. These were mixed with mirrors and panels showing helmets and weapons. This design was very bold. In 1969, this interior was moved to the Musée Carnavalet in Paris.

The next year, the Marquis de Montesquiou-Fézensac asked Ledoux to redesign his old castle at Mauperthuis. Ledoux rebuilt the castle and created new gardens. These gardens had fountains fed by an aqueduct (a water channel). He also built an orangery (a greenhouse for orange trees) and other large buildings. Not much of this remains today.

In 1764, he designed a house for Président Hocquart in Paris. It was a Palladian style house. This style often used a "colossal order," meaning tall columns that went up through several floors. This was different from the usual French style. The French way was to stack different types of columns on each floor, from simple to fancy.

On July 26, 1764, Ledoux married Marie Bureau in Paris. She was the daughter of a court musician. A friend helped him get a job as an architect for the Water and Forestry Department. From 1764 to 1770, he worked on churches, bridges, wells, fountains, and schools.

Some of his works from this time that still exist include the bridge of Marac. Also, the churches of Fouvent-le-Haut and Rolampont. He also designed the nave (main part) and entrance of Cruzy-le-Châtel church. And the quire (choir area) of Saint-Etienne d'Auxerre.

In 1766, Ledoux started designing the Hôtel d'Hallwyll in Paris. This building was praised and brought him new clients. The owner, Franz-Joseph d'Hallwyll, wanted to save money. So, Ledoux had to reuse parts of the old building. He wanted to build two colonnades (rows of columns) leading to a nymphaeum (a grotto with a fountain). But the space was too small. So, Ledoux painted a fake colonnade on a nearby wall to create the illusion of depth.

The success of the Hôtel d'Hallwyll led to a bigger job in 1767. This was the Hôtel d'Uzès in Paris. Here too, Ledoux kept parts of an older building. Today, the wooden panels from the main room, an early example of the Neoclassical style, are kept in the Carnavalet Museum in Paris.

Ledoux designed the Château de Bénouville in Calvados (1768–1769). It had a simple, almost plain, four-story front. It also had a prostyle portico (a porch with columns at the front). The main staircase was unusually placed in the middle of the garden side. This was normally where the main living room would be.

Ledoux visited England between 1769 and 1771. There, he learned about the Palladian style. Palladio was a famous Renaissance architect known for his Italian villas. After this trip, Ledoux often used the Palladian style. He would use a cube shape with a front porch of columns. This made even small buildings look grand.

In this style, he built a house for Marie Madeleine Guimard in 1770. He also designed houses for Mlle Saint-Germain, Attilly, and the poet Jean François de Saint-Lambert. Most notably, he built the Music Pavilion at the Château de Louveciennes (1770–1771). This was for Madame du Barry, an important friend of the King. Her support helped Ledoux in later years.

Later Works

With his reputation growing, Ledoux started designing even bigger projects. The Hôtel de Montmorency in Paris was from this time. It had a main front with Ionic columns above a rough-looking ground floor. Statues of famous Montmorency family members decorated the roof. However, the family didn't have much money left, so Ledoux had to build it cheaply.

In 1775, Ledoux went to Kassel, Germany. He became the "Controller and Organizer of Buildings for Hesse." Back in Paris, he reviewed plans for the Museum Fridericianum and a new town entrance. He finished this work in 1776.

Ledoux was interested in working for the Royal Administrations Department. This department dealt with public buildings. Thanks to the influence of Madame du Barry, Ledoux was asked to modernize the Salines de l'Est (Eastern Saltworks). This was a group of salt factories. In 1771, Ledoux became the Inspector of saltworks in Franche-Comté. He held this job until 1790.

The Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans (1775–1778)

In the 1700s, salt was very important and valuable. The king made a lot of money from a salt tax called the gabelle. In the Franche-Comté region, salt was taken from salty underground water. This was done by boiling the water in furnaces fueled by wood.

Usually, saltworks were built near the wells. Wood was brought from nearby forests. But Ledoux had a different idea. He decided to build the saltworks near the forests instead of the salt water source. He thought it would be easier to transport water through a canal than to transport lots of wood. So, the Fermiers Généraux (tax collectors) decided to build a new factory near the forest of Chaux. The salty water would be brought there by a new canal.

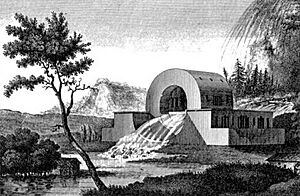

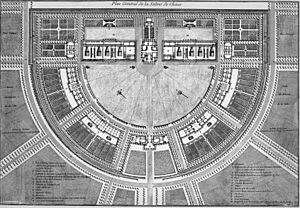

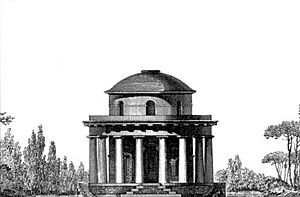

The design for the Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans is seen as Ledoux's greatest work. It was approved by the king. This factory was meant to be the first part of a huge, grand plan for a new ideal city. The first part was built between 1775 and 1778.

The entrance has a massive Doric portico (a porch with columns). It was inspired by the ancient temples at Paestum. Inside, a huge hall feels like you are entering a real salt mine. It has decorations that show nature's power and human cleverness. This reflected ideas from thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

The entrance building opens into a large, open, semicircular space. Ten buildings are arranged in a semicircle around it. These include the cooper's forge (where barrels were made) and workers' homes. Along the straight side are the salt extraction workshops and office buildings. In the very center is the director's house, which also had a chapel.

This circular plan was important for two reasons. First, a circle is a perfect shape. It suggested a harmonious place for work and an ideal city. Second, it reflected ideas about organization and watching over workers. It was similar to the Panopticon idea by Jeremy Bentham.

The saltworks struggled to make money. It closed in 1790 because of the French Revolution. So, the dream of a successful factory that was also a royal residence and a new city ended.

For a short time in the 1920s, the saltworks were used again. But they closed for good due to competition. For many years, the buildings fell apart. Then, they were named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1982. They were then restored and became a local cultural center.

The Theatre of Besançon

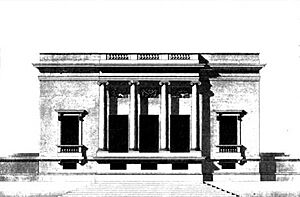

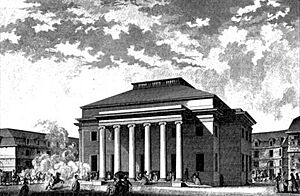

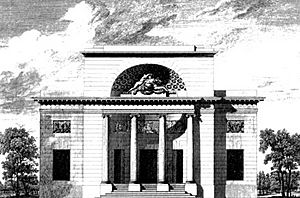

In 1784, Ledoux was chosen to design a theater in Besançon, France. The outside of the building was a plain Palladian cube. It only had a simple Grecian-style portico with six Ionic columns.

While the outside looked modern, the inside was revolutionary. Public theaters were rare in French provinces. And where they did exist, only nobles had seats. Others had to stand. Ledoux thought this was unfair. So, he designed the Besançon theater to be more equal. Everyone would have a seat. This idea was seen as very radical by some. The rich nobles did not want to sit next to common people.

However, Ledoux found an ally in Charles André de la Coré, a forward-thinking official. He agreed to the new plan. Still, it was decided that social classes would be separated. The theater was the first to have seats for the public on the ground floor. Above them was a raised balcony for government workers. Above that were boxes for the rich, and smaller boxes for the middle class. So, Ledoux achieved his goal. The theater was a place for everyone to enjoy together, but still kept social order.

The seating was not the only new idea. Ledoux also made the stage wings and scenery bigger. This gave the stage more depth than usual. Besançon was also the first theater to have musicians play in an orchestra pit below the stage. The building was highly praised when it opened in 1784.

Homes and Businesses

Ledoux was a Freemason. He took part in ceremonies with his friend William Thomas Beckford. These took place in a house he built for Mme d'Espinchal in Paris.

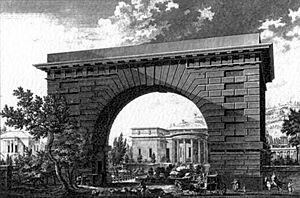

He knew a lot about the world of finance and the people in it. He designed a large house and park for Praudeau de Chemilly, a government treasurer. One of his most notable city houses was for the widow of a banker named Thélusson. This classical mansion was a popular place for Paris high society. It was in a large garden. The house had a huge entrance for carriages, shaped like a triumphal arch with columns. The round main room had columns in the center that held up the ceiling.

For a client named Hosten, Ledoux designed a group of rental apartments. They were built so that more could be added later. He also designed the gardens of Zephyr and Flora around a warehouse.

Buildings for the Tax Collectors

While working on the saltworks, Ledoux became an architect for the ferme générale (the tax collection company). He built a salt storage building for them in Compiègne. He also planned their large main office in Paris.

Charles Alexandre de Calonne, the finance minister, had an idea from the chemist Antoine Lavoisier. They wanted to build a wall around Paris. This would stop people from smuggling goods and avoiding taxes. This famous Wall of the Farmers-General was planned to have sixty tax-collecting offices. Ledoux was asked to design these buildings. He grandly called them "les Propylées de Paris" (the "Gates of Paris"). He wanted them to look important and show their purpose.

To quickly stop protests from Parisians, the project was done fast. Fifty tax barriers were built between 1785 and 1788. Most were destroyed in the 1800s. Very few remain today. The ones at La Villette and Place Denfert-Rochereau are the only ones that still look similar to their original design.

Sometimes, the entrance had two identical buildings. Other times, it was a single building. The shapes were classic: round buildings (like at Heap, Reuilly), or round buildings on top of a Greek cross (like at La Villette). There were also cube-shaped buildings with columns (Picpus), Greek temples (Gentilly), and tall columns (le Trône).

At Place de l'Étoile, the buildings had columns mixed with cube and cylinder shapes. These looked like the director's house at Arc-et-Senans. The Bureau des Bonshommes had a curved wall with columns, similar to Madame du Barry's pavilion. Ledoux mostly used the Doric style. He also used rough, textured stone.

This bold construction faced criticism. People complained about the politics behind it and Ledoux's designs. Critics like Antoine Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy said he took too many liberties with old architectural rules. Louis Petit de Bachaumont called it a "monument to enslavement and despotism." In his book Tableau de Paris (1783), Louis-Sébastien Mercier called the tax offices "tax dens turned into columned palaces." He exclaimed, "Ah! Monsieur Ledoux, you are a terrible architect!" Because of these strong opinions, Ledoux was removed from his official duties in 1787.

Difficult Times

At the same time, work on the law courts of Aix-en-Provence was stopped. Ledoux was accused of wasting government money. When the Revolution began, his rich clients either left France or were executed. His career and projects stopped. The tax wall he designed also started to be torn down. By June 1790, the tax company had moved into Ledoux's buildings. But the tax itself was removed in May 1791, making the buildings useless.

As a symbol of the old tax system, Ledoux, who had become wealthy, was arrested. He was sent to La Force Prison. While imprisoned, he designed a school for agriculture. It is thought that the painter Jacques-Louis David might have helped him avoid execution. But he lost his favorite daughter, and his other daughter sued him.

Ledoux was eventually released. He stopped building and focused on publishing his complete works. Since 1773, he had been engraving his buildings and plans. But his style kept changing, so the engravers constantly had to redo their plates. Ledoux's architecture became more detailed and grand, with smoother walls and fewer openings. An old drawing of the Louveciennes Pavilion by Sir William Chambers looks different from the engraving published in 1804. This shows how much Ledoux changed his designs.

While in prison, Ledoux started writing a text to go with his engravings. Only the first volume was published during his lifetime, in 1804. It was called L'Architecture considérée sous le rapport de l'art, des mœurs et de la législation. It showed the Besançon theater, the Arc-et-Senans saltworks, and the city of Chaux.

He passed away in Paris in 1806.

Utopian Ideas

Around the time of the royal saltworks, Ledoux developed his new ideas for city planning and architecture. He wanted to use architecture to improve society. He imagined an ideal city full of symbols and meanings. Along with Étienne-Louis Boullée, who designed a huge monument for Newton, Ledoux is seen as a pioneer of utopian ideas in architecture.

Boullée and Ledoux greatly influenced later architects who used the Greek Revival style. Especially Benjamin Henry Latrobe, who brought this style to public buildings in the United States. He hoped that the spirit of ancient Athenian democracy would be reflected in buildings for the new American democracy.

After 1775, Ledoux showed his first ideas for the town of Chaux to Turgot. This town was centered around the royal saltworks. The project was always being improved but was never built. The engravings were started in 1780 and probably finished by 1799. They were finally published in 1804 in his book L'Architecture considerée.

As a radical architect who taught at the École des Beaux-Arts, he created a unique architectural style. He designed a new type of column made of alternating cylinder and cube shapes. This was for their visual effect. At this time, people were returning to ancient styles. They also liked a "rustic" or natural look.

Works

Buildings Constructed

- Decoration of Café militaire (or Café Godeau), rue Saint-Honoré, Paris, 1762 (now at Musée Carnavalet, Paris)

- Château de Mauperthuis (Seine-et-Marne), 1763 (destroyed)

- Hôtel du président Hocquart, 66 rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin, Paris, 1764-1765 (destroyed)

- Hôtel d'Hallwyll, 28 rue Michel-le-Comte and 15 rue de Montmorency, Paris, 1766: This is the only private house Ledoux built in Paris that still exists.

- Hôtel d'Uzès, rue Montmartre, Paris, 1767 (destroyed around 1870): The wooden panels from the main room are at the Carnavalet Museum.

- Château de Bénouville, Bénouville, Calvados (near Caen), 1768-1769: Now houses a regional accounting office.

- Hôtel de la présidente de Gourgues, 53 rue Saint-Dominique, Paris (reconstructed)

- Hôtel of Mlle Guimard, Chaussée-d'Antin, Paris (destroyed)

- Maison de Mlle Saint-Germain, rue Saint-Lazare, Paris, 1769-1770 (destroyed)

- Pavillon Saint-Lambert, Eaubonne (destroyed)

- Pavillon d'Attilly, faubourg Poissonnière, Paris, 1771 (destroyed)

- Pavillon de musique de Mme du Barry, Louveciennes, 1770–1771

- Hôtel de Montmorency, intersection of rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin and boulevard, Paris, 1772 (destroyed): The woodwork from the round main room is at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans (1774–1779) (recognized as a historic monument of France and a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1982)

- Théâtre de Besançon, 1778–1784

- Hôtel Thellusson, rue de Provence, Paris, 1778 (destroyed in 1826)

- Hôtel de Mme d'Espinchal, Rue des Petites-Écuries (Paris), Paris (destroyed)

- Parc de Bourneville, La Ferté-Milon (Aisne)

- Grenier à sel (salt storage) of Compiègne (Oise)

- Siège de la Ferme générale (headquarters of the tax company), rue du Bouloi, Paris

- Pavillons et barrières de l'Octroi de Paris (tax collection buildings) (see Wall of the Farmers-General) (1785).

Projects Designed (but not always built)

- Project of the town of Chaux, around the Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans, published in 1804:

- Overall plan

- Market

- House of the gardener

- Project for the prison and law courts of Aix-en-Provence, 1785–1786

- The project of immeuble-loyer (rental building), 1792

Publications

In 1804, a book was published that included his works from 1768 to 1789. It was called L'Architecture considérée sous le rapport de l'art, des mœurs et de la législation.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Claude-Nicolas Ledoux para niños

In Spanish: Claude-Nicolas Ledoux para niños