Colonial Chile facts for kids

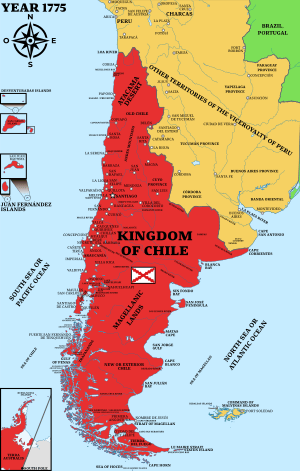

Colonial Chile was a special time in Chile's history, lasting from 1600 to 1810. This period started after a big event called the Destruction of the Seven Cities and ended when the Chilean War of Independence began. During these years, the main part of Chile was controlled by the Captaincy General of Chile, which was part of the Spanish Empire.

This era was marked by a long-lasting conflict between the Spaniards and the native Mapuche people, known as the Arauco War. Society in Colonial Chile was divided into different groups, like the Peninsulars (Spaniards born in Spain), Criollos (Spaniards born in America), Mestizos (people of mixed Spanish and Indigenous heritage), Indigenous people, and Black people. Compared to other Spanish colonies, Chile was seen as a "poor and dangerous" place.

Contents

Life in Colonial Chile: Society and People

Colonial Chilean society had a strict system, almost like a ladder, where people had different rights and roles.

Who Lived in Colonial Chile?

- Criollos: These were Spaniards born in America. They had many advantages, like owning encomiendas. An encomienda was a system where they were given control over groups of Indigenous people to work for them. Criollos could also hold some government jobs.

- Mestizos: At first, there weren't many Mestizos. But over time, they became the largest group in Chile. They were people with mixed Spanish and Indigenous backgrounds. Their place in society often depended on how they looked, not just their family history.

- Indigenous People: They were at the bottom of society. Many were forced to work in the encomienda system. Sadly, their numbers went down because of diseases and mixing with other groups. Mapuche, Huilliche, and Pehuenche people living south of La Frontera were mostly outside this colonial society.

- Black People: Spanish settlers also brought African slaves to Chile. While they were a small group, they were very expensive to bring and keep. They often worked as housekeepers or in other trusted roles.

- Peninsulars: These were Spaniards born in Spain. They were a small group but held important government jobs. This sometimes made the Criollos feel resentful.

Over time, many Basque people from Spain came to Chile. They mixed with the wealthy Criollos and formed a new upper class.

Families and Marriage

In the 1500s, many Spanish conquerors left their wives in Spain and married Indigenous women in Chile. However, as time went on, people in Chile became more faithful in their marriages.

How Chile Was Governed

The government of Chile, also known as Nueva Toledo, was created in 1534. It was first led by Diego de Almagro. Chile remained a colony of the Spanish Empire until 1818, when it declared its independence.

In the 1700s, the Spanish government made changes to how Chile was organized. They divided Chile into large areas called intendencias (provinces). These were then split into smaller partidos (counties), which were like today's communes.

By the end of the 1700s, there were two main intendencias: Santiago and Concepción. A third one, Coquimbo, was created in 1810. The area of Chiloé was also important, but it reported directly to the Viceroy (a high Spanish official) instead of the governor of Chile.

Work and Labor in Colonial Chile

The Encomienda System

In the 1500s, the Spanish in Chile needed many workers for their farms and mines. They used a system similar to slavery, which caused many Indigenous people to die. To stop this, the Spanish Crown introduced the encomienda system. However, in Chile, settlers often still treated Indigenous workers like slaves. Wealthy Spanish settlers faced opposition from Jesuits, Spanish officials, and the Mapuche people who resisted this system.

As the number of Indigenous people decreased in the 1600s, the encomienda system became less important. The encomienda system was finally ended in Chiloé in 1782, and in the rest of Chile by 1789.

Slavery

Slavery was a legal way of organizing labor in Chile from 1536 to 1823. However, it was never the main way people worked. The number of Black slaves increased between 1580 and 1660. This slowed down when Portugal, a major slave trader, lost some of its trading posts.

The Spanish Crown officially banned the enslavement of Indigenous people. But after the Mapuche uprising of 1598–1604, which led to the Destruction of the Seven Cities, the Spanish declared that Mapuches captured in war could be enslaved. This made it legal for Spaniards to raid Mapuche lands and capture people to sell as slaves. Mapuche slaves were often sent north to places like La Serena and Lima. This type of slavery was abolished in 1683. By then, free Mestizo workers were cheaper than owning slaves.

Chile's Economy

After the Spanish cities in the south were destroyed around 1598, Chile's economy changed. The main gold mines and Indigenous labor sources were lost. The colony then focused on the central valley. This area became more populated and important for the economy. Like other parts of Spanish America, Chile's economy shifted from mining to farming and raising animals.

Many poor and landless people appeared in Chile between 1650 and 1800. To help them, the government started founding new cities and giving land nearby. From 1730 to 1820, many farmers settled near older cities like La Serena, Valparaíso, Santiago, and Concepción. This was popular because it meant they had more customers for their farm products.

Farming and Crops

Chile started sending cereals like wheat to Peru in 1687. This happened after an earthquake and a plant disease hit Peru's crops. Chile's soil and climate were better for growing cereals. Chilean wheat was also cheaper and better quality than Peruvian wheat. The Chilean Central Valley, La Serena, and Concepción were key areas for growing wheat for export.

The 1687 Peru earthquake also hurt Peru's wine industry. This led to Chile becoming a more important wine-making region.

Mining for Metals

Mining in Chile was limited in the 1600s. However, it saw a big comeback in the 1700s. Gold production increased a lot, and silver production also grew significantly during this century.

Trading Goods

In the 1600s, Chile's economy was less important than rich mining areas like Potosí in Peru. Chile mainly exported animal products to the rest of the Viceroyalty of Peru. These included animal fat (suet), dried meat (charqui), and leather. This trade was so important that the 1600s were called the "century of suet" by a Chilean historian. Other exports included dried fruits, mules, wines, and small amounts of copper.

Direct trade with Spain began in the 1700s. This was mainly for exporting gold, silver, and copper from Chilean mines. At the same time, Spain's trade control over its colonies weakened. Smugglers from England, France, and the United States became more common.

Logging and Wood

Cutting down trees was not a major industry in colonial Chile, except in the Chiloé Archipelago and Valdivia. These areas exported wooden planks to Peru. After Valdivia was destroyed in 1599, Chiloé became even more important for supplying Fitzroya wood to Peru.

Building Ships

In the 1700s, Valdivia's shipbuilding industry was at its peak. It built many ships, including large frigates. Other shipyards in Chile were in Concepción and the Chiloé Archipelago. Chiloé built most of Chile's ships until the mid-1700s.

War and Protection

The Arauco War

In 1550, Pedro de Valdivia wanted to control all of Chile. He traveled south to conquer Mapuche lands. Between 1550 and 1553, the Spanish founded several cities in Mapuche territory, like Concepción and Valdivia. They also built forts.

After these early conquests, the Arauco War began. This was a long period of fighting between the Mapuches and the Spaniards. The Mapuches did not have a tradition of forced labor like some other Indigenous groups, and they refused to serve the Spanish. The Spanish, especially those from certain regions, came from a very violent society. The Mapuches often attacked Spanish cities between 1550 and 1598. The war was mostly a low-level conflict.

A major event happened in 1598. Mapuche warriors, led by Pelantaro, ambushed and killed Governor Martín García Óñez de Loyola and all his soldiers. This led to a big uprising among the Mapuches and Huilliches. Spanish cities like Angol, La Imperial, Osorno, and Valdivia were destroyed or abandoned. Only Chillán and Concepción survived the attacks. Most of Chile south of the Bío Bío River became free from Spanish rule.

In 1640, the Spanish Empire faced a rebellion in Spain itself. Because the Arauco War was so long and expensive, the Spanish Crown ordered a peace agreement with the Mapuche. This was called the Parliament of Quillín. The Mapuche got a peace treaty and recognition from the Spanish Crown, which was unique for an Indigenous group in the Americas. This treaty brought peace for a while, but fighting still broke out, especially in 1655.

Pirates and Corsairs

During colonial times, the Spanish Empire spent a lot of money to build forts along the Chilean coast. This was because Dutch and English pirates and corsairs (private ships allowed to attack enemy ships) often raided the coast.

In 1600, some Huilliche people joined a Dutch corsair named Baltazar de Cordes to attack the Spanish settlement of Castro. The Spanish worried that the Dutch might team up with the Mapuches and build a base in southern Chile.

The Dutch occupation of Valdivia in 1643 caused great alarm. This led to the construction of the Valdivian Fort System, which began in 1645.

After the Seven Years' War, the Valdivian Fort System was strengthened starting in 1764. Other important places like the Chiloé Archipelago, Concepción, Juan Fernández Islands, and Valparaíso were also prepared for possible English attacks.

In the 1770s, Spain and Great Britain were at war again. Spanish officials in Chile were warned that a British fleet might attack. Money was sent to the garrisons (military bases) at Valparaíso and Valdivia. However, the attack never happened.

|

See also

In Spanish: Chile colonial para niños

In Spanish: Chile colonial para niños