Constantin von Tischendorf facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Doctor

Constantin von Tischendorf

|

|

|---|---|

Constantin von Tischendorf, around 1870

|

|

| Born |

Lobegott Friedrich Constantin (von) Tischendorf

18 January 1815 Lengenfeld, Kingdom of Saxony

|

| Died | 7 December 1874 (aged 59) |

| Nationality | German |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | theology |

| Signature | |

|

|

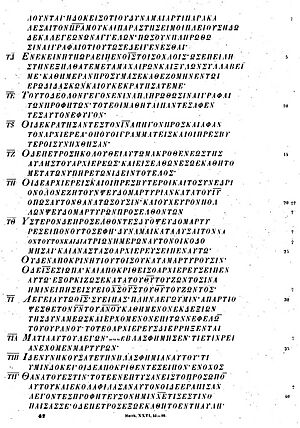

Lobegott Friedrich Constantin (von) Tischendorf (born January 18, 1815 – died December 7, 1874) was an important German scholar. He studied the Bible very closely. In 1844, he made an amazing discovery. He found the world's oldest and most complete Bible. This Bible was written around the mid-4th century. It is called the Codex Sinaiticus. He found it at Saint Catherine's Monastery near Mount Sinai.

Because of his discovery, Tischendorf received special honors. Both the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge gave him honorary doctorates in 1865. Earlier, as a student in the 1840s, he became well-known internationally. He managed to read and understand the Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus. This was a very old Greek manuscript of the New Testament from the 5th century.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Constantin von Tischendorf was born in Lengenfeld, Saxony. His father was a doctor. In 1834, he started studying at the University of Leipzig. There, he became very interested in the New Testament. He wanted to find the oldest Bible texts. His goal was to make the New Testament as close to the original as possible.

In 1838, he earned his Doctor of Philosophy degree. After that, he worked as a teacher near Leipzig. He also traveled through parts of Germany and Switzerland. These trips helped him prepare for his big work. He wanted to study the New Testament text very carefully.

His Work and Discoveries

In 1840, Tischendorf became a university lecturer. He wrote about different versions of the New Testament. These early studies showed him that he needed to find and compare more old manuscripts. He believed this was the only way to get the most accurate text.

From 1840 to 1843, he worked in Paris. He spent his time at the Bibliothèque nationale de France. He compared many old texts there. He also helped a publisher create new editions of the Greek New Testament. One of his biggest achievements was reading the Codex Ephraemi Syri Rescriptus. This was a palimpsest. A palimpsest is a document where the original writing was erased. Then, new writing was put on top. Tischendorf was very skilled at reading these old, hidden texts. His success made him famous. It also helped him get support for more trips to find ancient writings.

After Paris, he became a professor in Leipzig. He also started publishing a book about his travels. In 1843, he visited Italy. Then he went to Egypt, Sinai, and the Levant.

Finding the Codex Sinaiticus Bible

In 1844, Tischendorf made his first trip to Saint Catherine's Monastery. This monastery is at the foot of Mount Sinai in Egypt. There, he found a part of what would become known as the oldest complete New Testament.

He saw many old pages in a basket. The monks were using these old papers to start fires. Tischendorf was shocked. He asked if he could have them. The monks gave him 43 pages. These pages contained parts of the Old Testament. He gave these pages to King Frederick Augustus II of Saxony. The King had helped fund Tischendorf's journey. These 43 pages are now at the Leipzig University Library. They are called the Codex Friderico-Augustanus.

Some people have doubted the story of saving the old pages from the fire. But Tischendorf himself wrote that the monks told him the basket's contents had already been used for fire twice.

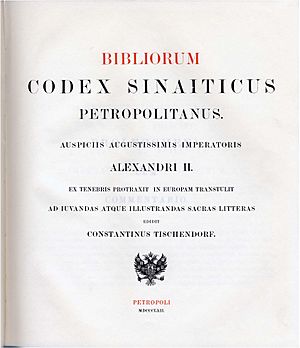

In 1853, Tischendorf visited the monastery again. But he didn't find anything new. He went a third time in 1859. This time, Tsar Alexander II of Russia supported his trip. On February 4, his last day there, he was shown a very important text. He immediately knew it was special. This was the Codex Sinaiticus. It was a Greek manuscript. It contained the complete New Testament and parts of the Old Testament. It dated back to the 4th century.

Tischendorf convinced the monks to give the manuscript to Tsar Alexander II. The Tsar then paid for it to be published in 1862. Some people thought Tischendorf bought manuscripts cheaply from monks. But he always defended the monks' rights. It took about 10 years for the monastery to officially give the manuscript to the Tsar. This was because the monastery's leader had to be re-elected. The Tsar paid 9000 Rubles for the Codex. He also promised to protect Greek-Orthodox Christians. The document confirming this gift was thought to be lost. But it was found again in St Petersburg in 2003.

In 1869, the Tsar gave Tischendorf the noble title "von". This was a great honor. 327 copies of the Codex were printed for the Tsar. Tischendorf worked very hard on this. He even worked nights to create special print characters. These characters matched the handwriting of the four scribes who wrote the original Codex. This hard work may have led to his early death. The Codex then went to the Imperial Library in St. Petersburg.

In 1933, the Soviet Government sold the Codex Sinaiticus. It was sold for 100,000 pounds to the British Museum in London.

Publishing the Greek New Testament

In 1849, Tischendorf published his major work, Novum Testamentum Graece. This means "Greek New Testament". It included rules for studying old texts. These rules are still helpful for students today.

Here are some of his main rules:

- Always look for the text in the oldest documents. Especially Greek manuscripts.

- If a reading is only found in one old document, it might be wrong.

- Readings that come from copyists' mistakes should be rejected.

- In similar passages, like in the Synoptic Gospels, the ones that are not exactly the same are often better. This is because copyists sometimes tried to make them match too much.

- When there are different readings, choose the one that might have led to the others.

- The readings must fit the style of Koine Greek or the writer's specific style.

Tischendorf traveled tirelessly to find old manuscripts. He wanted to understand the history of the sacred text. He hoped to find the true text written by the Twelve apostles.

He also published other important works. These included editions of the Codex Amiatinus in 1850. He also published the Septuagint, which is the Greek version of the Old Testament. In 1859, he became a full professor of theology. He also got a special professorship in Biblical paleography. This is the study of old writing.

Tischendorf was also friends with famous musicians. These included Robert Schumann and Felix Mendelssohn. His personal library was bought by the University of Glasgow after his death. You can still see books from his collection there.

Death

Lobegott Friedrich Constantin (von) Tischendorf died in Leipzig on December 7, 1874. He was 59 years old.

The Codex Sinaiticus

The Codex Sinaiticus is a very old manuscript. It contains texts from the New Testament from the 4th century. There are two other Bibles from around the same time. These are the Codex Vaticanus and Codex Alexandrinus. But they are not as complete as the Codex Sinaiticus. Many people believe the Codex Sinaiticus is the most important New Testament manuscript still existing. This is because no older manuscript is as complete. You can see the Codex at the British Library in London. You can also view a digital version online.

Tischendorf's Goal

Tischendorf spent his life searching for old Bible manuscripts. He believed it was his job to provide a Greek New Testament. This text had to be based on the oldest possible scriptures. He wanted to be as close as possible to the original writings. His biggest discovery was at Saint Catherine's Monastery on the Sinai Peninsula.

In 1862, Tischendorf published the text of the Codex Sinaiticus. He did this for the 1000th Anniversary of the Russian Monarchy. He made a fancy four-volume copy. He also made a cheaper text edition. This was so all scholars could study the Codex.

Tischendorf worked constantly on editing texts. He mainly focused on the New Testament. He worked so hard that he became ill in 1873. His main reason for this work was to prove scientifically that the words of the Bible had been passed down reliably over many centuries.

His Publications

His most important work was the "Critical Edition of the New Testament."

He published many editions of his New Testament text. The main ones were in 1841, 1849, 1859, and 1869–72. The 1849 edition was very important. It used a lot of new critical material. In his eighth edition (1869–72), he gave a lot of importance to the Sinaitic manuscript. He also used information from his friend Samuel Prideaux Tregelles.

Tischendorf also worked on the Greek Old Testament. His edition of the Roman text was useful when it came out in 1850. He also published works on the New Testament apocrypha. These are writings that are similar to the New Testament but are not part of the official Bible. He also wrote books defending the Bible, like Wann wurden unsere Evangelien verfasst? (When Were Our Gospels Written?).

Copies of Manuscripts

- Codex Ephraemi Syri rescriptus, sive Fragmenta Novi Testamenti, Leipzig 1843

- Codex Ephraemi Syri rescriptus, sive Fragmenta Veteris Testamenti, Leipzig 1845

- Notitia editionis codicis Bibliorum Sinaitici (Leipzig 1860)

- Anecdota sacra et profana (Leipzig 1861)

Editions of Novum Testamentum Graece

- Novum Testamentum Graece. Editio stereotypa secunda, (Leipzig 1862)

- Novum Testamentum Graece. Editio Quinta, Leipzig 1878

- Novum Testamentum Graece. Editio Septima, Leipzig 1859

Eighth Edition

- Gospels: Novum Testamentum Graece: ad antiquissimos testes denuo recensuit, apparatum criticum omni studio perfectum, vol. I (1869)

- Acts–Revelation: Novum Testamentum Graece. Editio Octava Critica Maior, vol. II (1872)

- Prolegomena I–VI: Novum Testamentum Graece. Editio Octava Critica Maior, vol. III, Part 1 (1884)

- Prolegomena VII–VIII: Novum Testamentum Graece. Editio Octava Critica Maior, vol. III, Part 2 (1890)

- Prolegomena IX–XIII: Novum Testamentum Graece. Editio Octava Critica Maior, vol. III, Part 3 (1894)

- Novum Testamentum graece: recensionis Tischendorfianae ultimae textum. Leipzig 1881

LXX (Septuagint)

- Vetus Testamentum Graece iuxta LXX interpretes: Vetus Testamentum Graece iuxta LXX (Volume 1)

- Vetus Testamentum Graece iuxta LXX interpretes: Vetus Testamentum Graece iuxta LXX (Volume 2)

Other Publications

- Doctrina Pauli apostoli de vi mortis satisfactoria. Leipzig, 1837

- Novum Testamentum Graece. Paris, 1842

- Codex Ephraemi Syri rescriptus sive fragmenta utriusque testamenti. Leipzig, 1843

- Monumenta sacra inedita. Leipzig, 1846

- Codex Friderico-Augustanus. Leipzig, 1846

- Evangelium Palatinum ineditum. Leipzig, 1847

- Novum Testamentum: Latine interprete Hieronymo. Leipzig, 1850

- Acta apostolorum apocrypha. Leipzig, 1851

- Synopsis evangelica. Leipzig, 1851

- Codex Claromontanus. Leipzig, 1852

- Evangelia apocrypha. Leipzig, 1853

- Novum Testamentum Triglottum. Leipzig, 1854

- Anecdota sacra et profana. Leipzig, 1855

- Pastor: Graece. Leipzig, 1856

- Novum Testamentum Graece et Latine. Leipzig, 1858

- Notitia editionis Codicis Bibliorum Sinaitici. Leipzig, 1860

- Aus dem heiligen Lande. Leipzig, 1862

- Vorworte zur sinaitischen Bibelhandschrift. Leipzig, 1862

- Novum Testamentum Sinaiticum. Leipzig, 1863

- Die Anfechtungen der Sinai-Bibel. Leipzig, 1865

- Wann wurden unsere Evangelien verfasst? Leipzig, 1865

- Apocalypses apocryphae. Leipzig, 1866

- Appendix Codicum celeberrimorum Sinaitici, Vaticani, Alexandrini. Leipzig, 1867

- Philonea. Leipzig, 1868

- Responsa ad calumnias romanas. Leipzig, 1870

- Die Sinaibibel, ihre Entdeckung, Herausgabe und Erwerbung. Leipzig, 1871

- Haben wir den ächten Schrifttext der Evangelisten und Apostel? Leipzig, 1873

- Liber Psalmorum. Leipzig, 1874

See also

In Spanish: Konstantin von Tischendorf para niños

In Spanish: Konstantin von Tischendorf para niños

- List of New Testament papyri

- List of New Testament uncials

- Agnes and Margaret Smith

- Editio Octava Critica Maior