Codex Sinaiticus facts for kids

| New Testament manuscript | |

|

|

| Name | Sinaiticus |

|---|---|

| Sign |  |

| Text | Greek Old Testament and Greek New Testament |

| Date | 4th century (after 325 AD) |

| Script | Greek |

| Found | Sinai, 1844 |

| Now at | British Library, Leipzig University Library, Saint Catherine's Monastery, Russian National Library |

| Cite | Lake, K. (1911). Codex Sinaiticus Petropolitanus, Oxford. |

| Size | 38.1 × 34.5 cm (15.0 × 13.6 in) |

| Type | Alexandrian text-type |

| Category | I |

| Note | very close to 𝔓66 |

The Codex Sinaiticus is a very old and important book. It's a Christian manuscript (a handwritten book) from the 4th century, which means it's about 1,600 years old! It contains most of the Septuagint (the Greek version of the Old Testament) and the complete New Testament in Greek. It also includes two other ancient Christian books: the Epistle of Barnabas and the Shepherd of Hermas.

This amazing book is written on parchment (animal skin prepared for writing) using a special style of capital letters called uncial script. The Codex Sinaiticus is one of only four "great uncial codices," which are very old manuscripts that originally held the entire Old and New Testaments. It's one of the earliest and most complete copies of the Bible we have today. In fact, it has the oldest complete copy of the New Testament!

Experts use the study of old writing styles, called palaeography, to figure out when old books were made. They believe the Codex Sinaiticus was written in the mid-4th century, sometime after 325 AD. It's considered one of the most important Greek texts of the New Testament, along with another ancient book called Codex Vaticanus.

The Codex Sinaiticus was found in the 19th century at Saint Catherine's Monastery in the Sinai Peninsula. More parts of it were found in the 20th and 21st centuries. Even though parts of this codex are now in four different libraries around the world, most of it is kept at the British Library in London, where people can go and see it.

Contents

What Does the Codex Sinaiticus Look Like?

The Codex Sinaiticus is like an early version of a modern book. It was made from vellum parchment, which is a very fine type of animal skin. Each page was originally quite large, about 40 by 70 centimeters.

The book was put together using groups of eight leaves, called "quires." Imagine eight pieces of parchment laid on top of each other and folded in half to make a block of pages. Several of these blocks were then sewn together to create the full book. Most of the parchment came from calf skins, but some was from sheep skins. Experts believe it took the hides of about 360 animals to make this huge book!

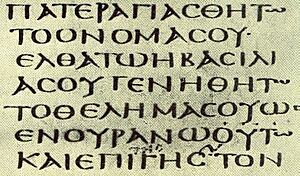

Each page of the text has about 12 to 14 Greek uncial letters per line. These lines are arranged in four columns, with 48 lines in each column. This layout made the book look a lot like the old papyrus scrolls when it was opened. However, the poetry books in the Old Testament were written differently, with each new poetic phrase on a new line, in only two columns per page.

The codex has almost 4 million uncial letters! The pages are rectangular, and the text block inside them has a special design that makes it look very balanced. A typographer named Robert Bringhurst called it a "subtle piece of craftsmanship." Making this book was very expensive. It's thought that the cost of the materials, the time it took for the scribes to copy it, and the binding was equal to what one person would earn in their entire lifetime back then.

How Was the Text Written?

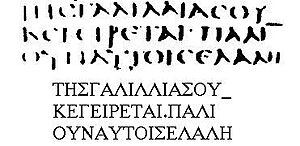

The New Testament part of the codex is written in scriptio continua. This means there are no spaces between words, which can make it a bit tricky to read! The writing style is called "biblical uncial" or "biblical majuscule."

The parchment was carefully prepared with lines to guide the scribes. The letters are written along these lines. There are no special marks (like breathings or polytonic accents) that help with pronunciation or emphasis in Greek.

The scribes used different types of punctuation, like high and middle dots, and colons. They also used a few ligatures, which are when two or more letters are joined together. Sometimes, the first letter of a new paragraph would stick out into the margin.

You'll also find "Nomina sacra" throughout the text. These are special holy words (like "God," "Lord," "Jesus," "Christ," "Spirit," "Son," "Man," "Heaven," "David," "Jerusalem," "Israel," "Mother," "Father," and "Savior") that are written in a shortened form with a line above them.

What Parts of the Bible Are in the Codex?

The part of the codex kept at the British Library has 346 and a half folios (pages), which means 694 pages in total. These pages are about 38.1 cm by 34.5 cm. This is more than half of the original book!

Of these pages, 199 belong to the Old Testament, including some books called deuterocanonical books (also known as apocrypha). The remaining 147 and a half pages are from the New Testament, along with the Epistle of Barnabas and part of The Shepherd of Hermas.

The deuterocanonical books found in the surviving Old Testament part are 2 Esdras, Tobit, Judith, 1 and 4 Maccabees, Wisdom, and Sirach.

The books of the New Testament in the codex are arranged in this order:

- The four Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, John)

- The letters of Paul (with Hebrews coming after 2 Thessalonians)

- The Acts of the Apostles

- The General Epistles (James, 1 Peter, 2 Peter, 1 John, 2 John, 3 John, Jude)

- The Book of Revelation

Even though large parts of the Old Testament are missing today, experts believe the codex originally contained the entire Old and New Testaments.

How Does the Text Compare to Other Bibles?

What Books Are Included?

The Old Testament part of the Codex Sinaiticus contains these books (or parts of them):

| 1 | Genesis (fragments) | 13 | 4 Maccabees |

| 2 | Leviticus | 14 | Book of Isaiah |

| 3 | Numbers (fragments) | 15 | Book of Jeremiah |

| 4 | Book of Deuteronomy (fragments) | 16 | Book of Lamentations |

| 5 | Book of Joshua (fragments) | 17 | Minor Prophets (missing Book of Hosea) |

| 6 | Book of Judges (fragments) | 18 | Book of Psalms |

| 7 | 1 Chronicles | 19 | Book of Proverbs |

| 8 | Ezra–Nehemiah | 20 | Ecclesiastes |

| 9 | Book of Esther | 21 | Song of Songs |

| 10 | Book of Tobit | 22 | Wisdom of Solomon |

| 11 | Book of Judith | 23 | Wisdom of Sirach |

| 12 | 1 Maccabees | 24 | Book of Job |

The New Testament books are:

| 1 | Gospel of Matthew | 10 | Philippians | 19 | Acts |

| 2 | Gospel of Mark | 11 | Colossians | 20 | James |

| 3 | Gospel of Luke | 12 | 1 Thessalonians | 21 | 1 Peter |

| 4 | Gospel of John | 13 | 2 Thessalonians | 22 | 2 Peter |

| 5 | Romans | 14 | Hebrews | 23 | 1 John |

| 6 | 1 Corinthians | 15 | 1 Timothy | 24 | 2 John |

| 7 | 2 Corinthians | 16 | 2 Timothy | 25 | 3 John |

| 8 | Galatians | 17 | Titus | 26 | Jude |

| 9 | Ephesians | 18 | Philemon | 27 | Revelation |

It also includes:

- Epistle of Barnabas

- Shepherd of Hermas

How Does it Compare to Other Old Manuscripts?

For most of the New Testament, the Codex Sinaiticus is very similar to the Codex Vaticanus and the Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus. These three manuscripts belong to what scholars call the Alexandrian text-type, which is known for being very old and reliable.

For example, in Matthew 5:22, both Sinaiticus and Vaticanus leave out the words "without a cause." This shows how closely related their texts are.

However, in parts of the Gospel of John (from John 1:1 to 8:38), the Codex Sinaiticus is different from Vaticanus and other Alexandrian manuscripts. In this section, it's more like the Codex Bezae, which is part of the Western text-type. This part of the codex has many corrections, showing that scribes worked hard to get the text right.

Scholars have found many differences between Sinaiticus and Vaticanus. One expert, Herman C. Hoskier, counted over 3,000 differences in the Gospels alone. Despite these differences, many scholars believe that Sinaiticus and Vaticanus came from an even older common source.

Over many centuries, from the 4th to the 12th, at least seven different people worked to correct the Codex Sinaiticus. This makes it one of the most corrected manuscripts known! One scholar, David C. Parker, estimates there are about 23,000 corrections in the entire codex.

What Passages Are Missing or Different?

The New Testament part of the Codex Sinaiticus is missing some verses and phrases that are found in many other Bible copies. For example, it doesn't include:

- Matthew 17:21

- Matthew 18:11

- Mark 16:9–20 (the "Long ending of the Gospel of Mark")

- John 7:53–8:11

- Acts 8:37

It also leaves out some phrases, like:

- In Matthew 5:44, it doesn't have "bless those who curse you, do good to those who hate you."

- In Matthew 6:13, it doesn't include "For Yours is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen." (part of the Lord's Prayer).

Some passages were originally included by the first scribes but later marked as doubtful or removed by correctors. For instance, in Matthew 24:36, the phrase "nor the Son" was first included, then marked as doubtful, and later the mark was removed.

The codex also has some unique readings or additions not found in many other manuscripts. For example:

- In Matthew 8:13, it adds a phrase about the centurion finding his slave well.

- In Matthew 13:54, it says "to his own Antipatris" which is a unique reading.

- In John 2:3, it has a longer phrase about the wine running out at the wedding.

The Story of the Codex Sinaiticus

Where Did it Come From?

Not much is known about the very early history of the Codex Sinaiticus. Some scholars thought it was written in Rome, but others believed it came from Egypt. Many now think it was created in Caesarea Maritima, an ancient city in what is now Israel. This city had a famous library, and it's possible the codex was made there.

How Old Is It Exactly?

We can be quite sure the codex was written between the early 4th century and the early 5th century. It couldn't have been written before 325 AD because it contains the Eusebian Canons, which were developed around that time. Some experts believe it was made around 360 AD, but newer research suggests it could be as late as the early 5th century.

One theory is that the Codex Sinaiticus might have been one of the fifty copies of the Bible that Roman emperor Constantine ordered from Eusebius after he became a Christian.

Who Wrote and Corrected It?

Originally, scholars thought four different scribes copied the codex. But later research showed there were actually three main scribes, known as Scribe A, Scribe B, and Scribe D.

- Scribe A wrote most of the Old Testament historical and poetic books, almost all of the New Testament, and the Epistle of Barnabas.

- Scribe B wrote the Prophets and the Shepherd of Hermas.

- Scribe D wrote the books of Tobit, Judith, part of 4 Maccabees, most of the Psalms, and the first few verses of Revelation.

Scribe D was considered the best writer, while Scribe A and Scribe B made more spelling mistakes.

Besides the original scribes, at least seven different correctors worked on the codex over time. The first corrections were made by scribes right after the book was copied. Later, in the 6th or 7th century, many more changes were made. A note in the codex says these later changes were based on "a very ancient manuscript that had been corrected by the hand of the holy martyr Pamphylus" (who died in 309 AD). This suggests these corrections were made in Caesarea Maritima.

How Was it Discovered?

The Codex Sinaiticus might have been seen as early as 1761 by an Italian traveler named Vitaliano Donati at Saint Catherine's Monastery. He wrote about finding "a great number of parchment codices" and "a Bible (made) of beautiful vellum."

The official discovery happened in 1844 when a German Bible scholar named Constantin von Tischendorf visited the monastery. He claimed he saw some parchment leaves in a waste-basket, which were about to be burned. He realized they were very old parts of the Septuagint. He was allowed to take 43 of these leaves, which he later published and named 'Codex Friderico-Augustanus'.

In 1859, Tischendorf returned to the monastery, this time with support from Tsar Alexander II of Russia. He claimed he was shown the rest of the Codex Sinaiticus. He later said he found it discarded in a rubbish bin, but the monastery denies this, and some people have questioned his story, noting the leaves were in "suspiciously good condition" for trash.

Tischendorf published the complete text of the codex in 1862. The full codex was later published in black and white by Kirsopp Lake in 1911 (New Testament) and 1922 (Old Testament).

Was it a Fake?

In 1862, a man named Constantine Simonides claimed that he had written the codex himself in 1839! He was known for having a controversial past with manuscripts. However, scholars like Henry Bradshaw defended Tischendorf's discovery, and Simonides' claims were later proven false. Recent discoveries of more fragments of the codex have confirmed its authenticity.

Not everyone was happy about the codex. Some scholars, like John William Burgon, who supported a different version of the Bible text, believed that Codex Sinaiticus (along with Vaticanus and Bezae) was a "corrupt" or "fabricated" document. However, this view is not widely accepted today.

What Happened to it Recently?

In the early 20th century, more fragments of the codex were found by Vladimir Beneshevich in the bindings of other manuscripts at Mount Sinai. These were also sent to St. Petersburg.

For many years, most of the codex was kept in the Russian National Library. But in 1933, the Soviet Union sold it to the British Museum (now the British Library) for £100,000.

In 1975, during restoration work, monks at Saint Catherine's Monastery found a hidden room with many parchment fragments. Among them were twelve more complete leaves from the Codex Sinaiticus! These included parts of the Pentateuch and the Shepherd of Hermas.

In 2005, a team of experts from different countries started a project to create a new digital version of the manuscript. This project uses special technology, like hyperspectral imaging, to photograph the manuscripts and look for hidden information, such as text that has faded or been erased.

Today, the entire Codex Sinaiticus is available online in digital form for everyone to study. You can see fully transcribed pages and images of each page, even with special lighting to show the texture of the parchment. In 2009, a student named Nikolas Sarris found another unseen fragment of the codex at Saint Catherine's Monastery, containing text from Book of Joshua 1:10.

Where Is the Codex Sinaiticus Now?

The Codex Sinaiticus is now divided into four parts:

- 347 leaves are in the British Library in London (199 from the Old Testament, 148 from the New Testament).

- 12 leaves and 14 fragments are still at the Saint Catherine's Monastery.

- 43 leaves are in the Leipzig University Library.

- Fragments of 3 leaves are in the Russian National Library in Saint Petersburg.

There has been some discussion about how Tischendorf obtained the manuscript from the monastery. The monastery believes it was stolen, pointing to a receipt from Tischendorf promising to return it. However, Russian scholars say that recently published documents, including a gift deed from 1868 signed by the Archbishop and monks, prove the manuscript was legally given. This issue is still debated, but everyone agrees that both the monks and Tischendorf deserve thanks for preserving this incredible historical treasure.

Why Is the Codex Sinaiticus Important?

The Codex Sinaiticus is considered one of the most valuable manuscripts we have. It's one of the oldest and likely very close to the original text of the Greek New Testament. It's the only ancient manuscript with the complete New Testament written in the uncial script, and the only ancient New Testament manuscript with four columns per page that still exists today.

Because it's so old (only about 300 years after Jesus's lifetime), some people believe it's more accurate than most other copies of the New Testament. For the Gospels, it's often seen as the second most reliable text (after Codex Vaticanus). For the Acts of the Apostles, its text is considered just as good as Vaticanus. For the Epistles, Sinaiticus is often thought to be the most reliable. However, for the Book of Revelation, its text is considered to be of lower quality compared to other manuscripts like Codex Alexandrinus.

See Also

- Biblical manuscript

- Codex Sinaiticus Rescriptus

- Differences between codices Sinaiticus and Vaticanus

- Fifty Bibles of Constantine

- List of New Testament uncials

- Syriac Sinaiticus