Daniel Shays facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Daniel Shays

|

|

|---|---|

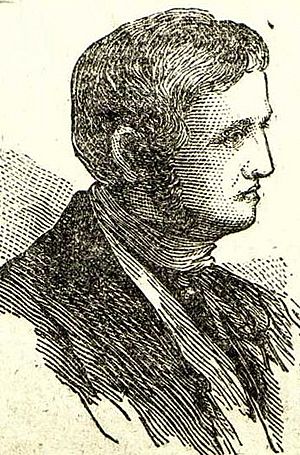

"An Authentic Portrait of the Chief Insurgent" from 1878's Our First Century by Richard Miller Devens

|

|

| Born | August 1747 |

| Died | (aged 78) |

| Resting place | Union Cemetery, Scottsburg, New York |

| Occupation | farmer, military officer |

| Known for | |

| Spouse(s) | Abigail Gilbert |

| Children | 6 |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1775 (militia) 1775–1780 (army) |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | Woodbridge's Regiment (militia) Varnum's Regiment 5th Massachusetts Regiment Corps of Light Infantry |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War Shays' Rebellion |

| Signature | |

Daniel Shays (born August 1747, died September 29, 1825) was an American soldier and farmer. He became well-known for his role in Shays' Rebellion. This was an uprising in Massachusetts between 1786 and 1787. It involved farmers and others who were upset about high taxes and debts.

Contents

Early Life of Daniel Shays

Daniel Ogden Shays was born in Hopkinton, Massachusetts. His parents, Patrick Shays and Margaret Dempsey, were immigrants from Ireland. Daniel was one of seven children in his family.

When he was young, Daniel worked as a farm laborer. In 1772, he married Abigail Gilbert. They settled in Shutesbury, Massachusetts, where Daniel owned a 68-acre farm. They had six children together.

Daniel Shays in the Revolutionary War

Daniel Shays joined the local militia just before the American Revolution began. He quickly became a sergeant in Benjamin R. Woodbridge's regiment.

Fighting for Independence

When the Battles of Lexington and Concord happened on April 19, 1775, Shays's unit was called to action. They marched to Boston and took part in the Boston campaign. Shays also fought bravely at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Because of his courage, he was made a second lieutenant soon after.

In late 1776, Shays joined Varnum's Regiment of the Continental Army. He served in battles in New York and New Jersey. On January 1, 1777, he was promoted to captain. He commanded a company in the 5th Massachusetts Regiment. That year, Shays fought in several battles in upstate New York, including the important Battles of Saratoga.

Later War Service

After Saratoga, Shays continued to serve in New York. He led a company in the Corps of Light Infantry. This group was commanded by General Anthony Wayne. Shays participated in the Battle of Stony Point in July 1779.

Later, he served under the Marquis de Lafayette. His company patrolled farmland along the Hudson River in New Jersey. Their job was to stop British troops from taking food from farms.

In 1780, Lafayette gave special swords to several officers, including Shays, to honor their service. Shays sold his sword to pay off some debts. He said it was fine because he already had another sword. However, some of his fellow officers did not approve.

Shays was also chosen by General George Washington to guard British officer John André. André had been captured while working with Benedict Arnold against the Americans. Shays was present when André was executed on October 2, 1780. Shays left the army shortly after, on October 14, 1780.

Shays' Rebellion: A Fight for Fairness

When Daniel Shays returned home, he faced a big problem: unpaid debts. He had not been fully paid for his time in the army. He soon found that many other veterans and farmers were in the same situation.

Why People Were Upset

Many people felt they were treated unfairly after the war. Business owners were trying to collect money from small farmers. This was to pay their own debts to European investors who had helped fund the war.

People in rural Massachusetts tried to ask the state government in Boston for help. They sent many requests, often asking for the government to print more paper money. This would make money less valuable, but it would also make it easier to pay off old debts. However, merchants and lenders, like Governor James Bowdoin, were against this idea. They would lose money if the currency became less valuable.

The government did not respond to the farmers' requests. Instead, Governor Bowdoin increased efforts to collect back taxes. The state also added a new property tax to pay off foreign debts. Even important figures like John Adams thought these taxes were "heavier than the People could bear."

Protests Against the Courts

The protests grew stronger in August 1786. The state government ended its session without addressing the people's concerns. On August 29, a group of protestors, including Shays, marched on Northampton. They successfully stopped the local court from meeting.

These protestors called themselves Regulators. They wanted to stop the legal actions that were taking away people's land and belongings. Governor Bowdoin spoke out against these actions but did not send soldiers right away.

When a similar protest shut down the court in Worcester on September 5, the local militia refused to help the governor. Many militia members supported the protestors.

Daniel Shays became more involved in the uprising in November. Some historians believe his role was made to seem bigger by the leaders in Boston. They wanted to make him look like a major villain.

On September 19, the Supreme Judicial Court accused eleven protest leaders of being "disorderly, riotous, and seditious." When the court was set to meet in Springfield on September 26, Shays and another leader named Luke Day tried to shut it down. However, the local militia commander, William Shepard, had already gathered 300 men to protect the courthouse. Shays and Day had about 1,200 men, but they only demonstrated outside the courthouse. The judges postponed and then canceled the court sessions. Shepard's forces, which had grown to 800 men, moved to the Springfield Armory, a place where weapons were stored.

Plan to Seize the Springfield Armory

On November 28, a group of government supporters arrested Job Shattuck and other protest leaders. This made the western protestors even more determined. They began planning to overthrow the state government.

Shays, Day, and other leaders organized their forces. Their main goal was to take control of the federal armory in Springfield. However, General Shepard had already taken control of the armory. He used its weapons to arm about 1,200 militia members.

The Attack and Its End

The rebels planned to attack the armory from three sides. Shays led one group, Luke Day led another, and Eli Parsons led the third. The attack was planned for January 25. But Luke Day changed his mind at the last minute and sent a message to Shays saying he would attack on the 26th.

Shepard's men intercepted Day's message. So, Shays and Parsons, with about 1,500 men, approached the armory on January 25, not knowing Day would not be there.

When Shays's forces got close to the armory, Shepard's militia was waiting. Shepard ordered warning shots. Then, he ordered two cannons to fire grape shot at Shays's men. Four rebels were killed and twenty were wounded. The rebels quickly retreated. Most of them fled north to Amherst. Day's forces also fled to Amherst.

General Benjamin Lincoln had gathered 3,000 men to deal with the rebels. When he heard about the Springfield incident, he marched his troops west. Shays led his rebel forces north and east to avoid Lincoln. They set up camp in Petersham. Along the way, they took supplies from local shops.

On the night of February 3–4, Lincoln led his militia on a difficult march through a snowstorm to Petersham. They surprised the rebel camp early in the morning. The rebels scattered quickly. Lincoln claimed to capture 150 men, but no officers were among them. Shays and other leaders escaped north into New Hampshire and Vermont.

About 4,000 people admitted to being part of the rebellion and received amnesty (a pardon). Several hundred were charged, but most were pardoned later. Eighteen men, including Shays, were found guilty and sentenced to death. However, most of these sentences were overturned or pardoned. Two men, John Bly and Charles Rose, were executed on December 6, 1787. Daniel Shays was pardoned in 1788 and returned to Massachusetts.

Later Life of Daniel Shays

Later in his life, Daniel Shays received a pension from the government. This was for the five years he served in the Continental Army without pay. He lived his final years in poverty, supporting himself with his pension and a small piece of land.

Daniel Shays died at age 78 in Sparta, New York. He was buried at Union Cemetery in Scottsburg.

Rededicated Grave Marker

The original gravestone for Daniel Shays had a mistake: his name was spelled "Shay." A descendant, Philip R. Shays, worked to fix this error. Since there wasn't enough space on the old stone, a new one was made. The new gravestone was officially dedicated in a ceremony on August 12, 2016.

See also

In Spanish: Daniel Shays para niños

In Spanish: Daniel Shays para niños