Deep Impact (spacecraft) facts for kids

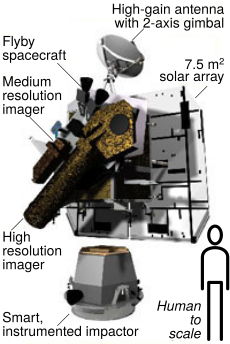

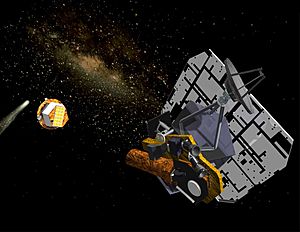

Artist's impression of the Deep Impact space probe after deployment of the Impactor.

|

|

| Mission type | Flyby · impactor (9P/Tempel) |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA · JPL |

| Mission duration | Final: 8 years, 6 months, 26 days |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Ball Aerospace · University of Maryland |

| Launch mass | Total: 973 kg Spacecraft: 601 kg (1,325 lb) Impactor: 372 kg (820 lb) |

| Dimensions | 3.3 × 1.7 × 2.3 m (10.8 × 5.6 × 7.5 ft) |

| Power | 92 W (solar array / NiH 2 battery) |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | January 12, 2005, 18:47:08 UTC |

| Rocket | Delta II 7925 |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral SLC-17B |

| Contractor | Boeing |

| End of mission | |

| Disposal | Contact lost |

| Last contact | August 8, 2013 |

| Flyby of Tempel 1 | |

| Closest approach | July 4, 2005, 06:05 UTC |

| Distance | 575 km (357 mi) |

| Tempel 1 impactor | |

| Impact date | July 4, 2005, 05:52 UTC |

| Flyby of Earth | |

| Closest approach | December 31, 2007, 19:29:20 UTC |

| Distance | 15,567 km (9,673 mi) |

| Flyby of Earth | |

| Closest approach | December 29, 2008 |

| Distance | 43,450 km (27,000 mi) |

| Flyby of Earth | |

| Closest approach | June 27, 2010, 22:25:13 UTC |

| Distance | 30,496 km (18,949 mi) |

| Flyby of Hartley 2 | |

| Closest approach | November 4, 2010, 13:50:57 UTC |

| Distance | 694 km (431 mi) |

Official insignia of the Deep Impact mission |

|

The Deep Impact mission was a NASA space probe launched on January 12, 2005. Its main goal was to study the inside of a comet called Tempel 1. To do this, it released a special "impactor" that crashed into the comet.

On July 4, 2005, the Impactor successfully hit the comet's center. This crash dug up material from deep inside the comet, creating a new impact crater. Pictures from the spacecraft showed that the comet was dustier and less icy than scientists thought. The impact also made a huge, bright cloud of dust, which hid the new crater from view.

Before Deep Impact, other missions like Giotto and Stardust only flew past comets. They could only take pictures of the surface from far away. Deep Impact was the first mission to actually dig into a comet. This made it very popular with the media, scientists, and even amateur astronomers around the world.

After its main mission, Deep Impact was used for more studies. It flew past Earth on December 31, 2007, to start a new mission called EPOXI. This mission had two goals: to study planets outside our solar system and to visit another comet called Hartley 2. Sadly, NASA lost contact with the spacecraft in August 2013 while it was heading for another asteroid flyby.

Contents

Why study comets?

The Deep Impact mission aimed to answer big questions about comets. Scientists wanted to know what comets are made of deep inside. They also wondered how deep the crater would be after the impact. Another question was where comets first formed in space.

By looking at the comet's makeup, astronomers hoped to learn how comets were born. They wanted to see if the inside was different from the outside. Watching the impact and what happened next helped scientists find answers.

The main scientist for the mission was Michael A'Hearn from the University of Maryland. He led a team of scientists from many different universities and research centers.

Spacecraft design

The Deep Impact spacecraft had two main parts. One part was the "Smart Impactor," which weighed about 372-kilogram (820 lb). It had a copper core and was designed to hit the comet. The other part was the "Flyby" section, weighing 601 kg (1,325 lb). This part stayed at a safe distance to take pictures of the comet during the crash.

The Flyby spacecraft was about 3.3 meters (10.8 ft) long. It had two solar panels to get power from the sun. It also had a shield to protect it from debris. The Flyby carried special cameras and instruments. These included the High Resolution Imager (HRI) and the Medium Resolution Imager (MRI). The HRI was best for looking at the comet's center. The MRI was a backup and helped guide the spacecraft in the last 10 days.

The Impactor had its own camera called the Impactor Targeting Sensor (ITS). This camera helped guide the Impactor towards the comet. It also took very close-up pictures of the comet's center. These pictures were sent to the Flyby spacecraft just before the Impactor was destroyed. The last picture from the Impactor was taken only 3.7 seconds before it hit.

The Impactor's main part, called the "Cratering Mass," was made of 100% copper. It weighed 100 kg. Copper made up almost half of the Impactor's total weight. Scientists chose copper because it's not usually found on comets. This meant they could easily tell the difference between the comet's material and the Impactor's material. Using copper was also cheaper than using explosives.

The Impactor didn't need explosives. It hit the comet at a speed of 10.2 kilometers per second (about 22,800 miles per hour). This speed gave it a huge amount of energy, like exploding 4.8 tons of TNT.

The mission's name, Deep Impact, was the same as a 1998 movie. In that movie, a comet also hits Earth.

Mission journey

Deep Impact launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station on January 12, 2005. It traveled 429 million km (267 million mi) in 174 days to reach comet Tempel 1. Its cruising speed was about 28.6 km/s (103,000 km/h; 64,000 mph).

On July 3, 2005, the spacecraft split into two parts: the Impactor and the Flyby. The Impactor then used its small engines to steer itself into the comet's path. It hit the comet 24 hours later at a speed of 10.3 km/s (37,000 km/h; 23,000 mph). The crash released energy equal to 4.7 tons of TNT.

Scientists thought the crash would make a crater up to 100 m (330 ft) wide. This is bigger than the Roman Colosseum. Later, the Stardust spacecraft visited Tempel 1 again in 2011. It measured the crater to be about 150 meters (490 ft) across.

Just minutes after the impact, the Flyby probe flew past the comet's center. It was only 500 km (310 mi) away. It took pictures of the crater, the cloud of material (called the ejecta plume), and the whole comet. Many telescopes on Earth and in space also watched the event. These included Hubble, Chandra, and Spitzer. Even Europe's Rosetta spacecraft, which was far away, observed the impact. Rosetta helped figure out what gases and dust were kicked up by the crash.

Mission timeline

Before launch

The idea for a comet-impact mission was first suggested in 1996. But NASA engineers weren't sure they could hit such a small target. In 1999, a new and improved plan, called Deep Impact, was approved. It became part of NASA's Discovery Program for lower-cost spacecraft. The two parts of the spacecraft (Impactor and Flyby) were built by Ball Aerospace & Technologies.

Launch and early days

The probe was supposed to launch in December 2004. But NASA delayed it to test the software more. It successfully launched from Cape Canaveral on January 12, 2005. It was carried into space by a Delta II rocket.

Right after launch, Deep Impact went into "safe mode." This happened because of a small error in its temperature settings. But on January 13, 2005, NASA announced that the probe was working fine again.

In February 2005, the spacecraft fired its rockets to adjust its path. This was so accurate that the next planned adjustment was not needed. During tests, scientists found that the HRI camera's images were a bit blurry. But they used special software to fix the pictures and make them clear.

Journey to the comet

The "cruise phase" began on March 25, 2005. This was the long journey to comet Tempel 1. On April 25, 2005, the probe took its first picture of Tempel 1. It was still 64 million km (40 million mi) away!

On May 4, 2005, the spacecraft made another small course correction. This made its speed change by 18.2 km/h (11.3 mph). Rick Grammier, the project manager, said the spacecraft was performing "excellently."

The "approach phase" started about 60 days before the impact. This was when Deep Impact began to watch the comet closely. Scientists studied the comet's spin, activity, and dust. They also used images of distant stars to figure out the spacecraft's exact position.

On June 14 and 22, 2005, Deep Impact saw two bursts of activity from the comet. The second burst was six times bigger than the first. On June 23, the spacecraft made its final course adjustment. This small change was needed to aim the Impactor perfectly at the comet.

Impact day

The "impact phase" began on June 29, 2005. The Impactor separated from the Flyby spacecraft on July 3. The first pictures from the Impactor were seen two hours later.

The Flyby spacecraft then moved to a safe distance. It performed a 14-minute engine burn to slow down. The communication between the Flyby and the Impactor worked perfectly. The Impactor made three final adjustments in the last two hours before hitting the comet.

The Impactor was guided to hit the comet head-on. The crash happened on July 4, 2005, at 05:45 UTC. It was almost exactly when expected.

The Impactor sent back pictures until just three seconds before it hit. The Flyby spacecraft stored about 4,500 images from its cameras. It then sent these pictures to Earth over the next few days. The collision made the comet shine six times brighter than normal.

-

Comet Tempel 1, imaged from 4.2 million km at the start of Impact phase

What we learned

Mission control knew the Impactor hit the comet about five minutes after it happened. Don Yeomans, a scientist on the mission, said, "We hit it just exactly where we wanted to." The head of JPL, Charles Elachi, said, "The success exceeded our expectations."

After the impact, the first pictures showed existing craters on the comet. Scientists couldn't see the new crater right away because of the bright dust cloud. But later, it was found to be about 100 meters wide and up to 30 meters (98 ft) deep. Lucy McFadden, another scientist, said, "We didn't expect the success of one part of the mission [bright dust cloud] to affect a second part [seeing the resultant crater]. But that is part of the fun of science, to meet with the unexpected."

Data from the Swift X-ray telescope showed that the comet kept releasing gas for 13 days after the impact. About 5 million kg (11 million lb) of water and up to 25 million kg (55 million lb) of dust were lost from the impact.

The first results were surprising. The material dug up by the impact had more dust and less ice than expected. Scientists compared the material to talcum powder, not sand. They also found clays, carbonates, sodium, and crystalline silicates. Clays and carbonates usually need liquid water to form, and sodium is rare in space. Observations also showed that the comet was about 75% empty space. Its outer layers were like a snow bank. Scientists want to send more missions to other comets to see if they are similar.

Scientists think Tempel 1 formed far from the Sun, in the Uranus and Neptune Oort cloud region. Comets formed farther out should have more ices that freeze at low temperatures, like ethane, which was found in Tempel 1.

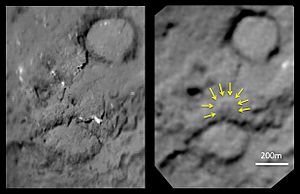

The crater up close

Because the first pictures of the crater weren't clear enough, NASA approved a new mission. It was called New Exploration of Tempel 1 (NExT). This mission used the existing Stardust spacecraft. Stardust had already studied Comet Wild 2 in 2004.

Stardust was sent on a new path to fly by Tempel 1 again. It passed about 200 km (120 mi) away on February 15, 2011. This was the first time a comet was visited by two different probes. It gave scientists a chance to see the crater made by Deep Impact more clearly. They also saw changes from the comet's recent trip closer to the Sun.

On February 15, 2011, NASA scientists finally saw the crater from Deep Impact in the Stardust images. The crater is estimated to be 150 meters (490 ft) wide. It has a bright mound in the middle, likely from material falling back into the crater.

Public interest

Media attention

The impact was a huge news event. It was talked about online, in newspapers, and on TV. There was real excitement because experts had different ideas about what would happen. Some thought the Impactor would go right through the comet. Others thought it would make a crater.

The day before the impact, the team at JPL felt very confident. They believed the spacecraft would hit Tempel 1. One team member said, "All we can do now is sit back and wait." More than 10,000 people watched the collision on a giant screen at Hawaii's Waikīkī Beach.

Experts used fun phrases to explain the mission. Iwan Williams said, "It was like a mosquito hitting a 747. What we've found is that the mosquito didn't splat on the surface; it's actually gone through the windscreen."

One day after the impact, a Russian astrologer sued NASA. She claimed the impact "ruined the natural balance of forces in the universe." Her lawsuit was dismissed. A Russian physicist said the impact had no effect on Earth. He noted that the comet's orbit changed by only about 10 centimeters (3.9 inches).

Send Your Name To A Comet

The mission had a cool campaign called "Send Your Name To A Comet!" People could submit their names online. About 625,000 names were collected. These names were then burned onto a small CD. This CD was attached to the Impactor.

Dr. Don Yeomans said this was a chance to "become part of an extraordinary space mission." He added that people's names could "hitch along for the ride." This idea helped get many people interested in the mission.

Amateur astronomers help

Time on big, professional telescopes like Keck is rare. So, Deep Impact scientists asked "advanced amateur, student, and professional astronomers" for help. They asked them to use smaller telescopes to watch the comet before and after the impact.

These observations helped scientists study the comet's gas, dust, and activity. By mid-2007, amateur astronomers had sent in over a thousand images of the comet.

One amazing observation came from students in Hawaii. They used the Faulkes Automatic Telescope over the Internet. They were among the first to get images of the impact. One amateur astronomer saw a bright cloud around the comet. Another published a map of the crash area using NASA images.

Musical tribute

The Deep Impact mission happened around the 50th anniversary of "Rock Around the Clock" by Bill Haley & His Comets. This was the first rock and roll song to reach No. 1. A music video was made using images of the impact and animation of the probe. It also showed Bill Haley & His Comets performing. NASA posted the video on its website.

On July 5, 2005, the original members of The Comets played a free concert. It was for hundreds of employees at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. This helped them celebrate the mission's success. Later, an asteroid was officially named 79896 Billhaley. The name mentioned the JPL concert.

Extended mission: EPOXI

Deep Impact went on an extended mission called EPOXI. This stands for Extrasolar Planet Observation and Deep Impact Extended Investigation. Its goal was to visit other comets.

Visiting Comet Hartley 2

In November 2007, the JPL team aimed Deep Impact toward Comet Hartley 2. This meant two more years of travel for Deep Impact. It included using Earth's gravity to speed up in December 2007 and December 2008.

On November 4, 2010, the EPOXI mission sent back images from comet Hartley 2. Deep Impact flew within 700 kilometers (430 mi) of the comet. It sent back detailed pictures of the comet's "peanut" shaped center and bright jets of gas.

Contact lost

On September 3, 2013, NASA announced that communication with the spacecraft was lost. This happened sometime between August 11 and August 14. The last message from the probe was on August 8.

On September 10, 2013, NASA explained that the spacecraft's computers seemed to be constantly restarting. This made it hard to send commands to the probe. Also, the solar panels might not have been facing the sun correctly to make power.

On September 20, 2013, NASA stopped trying to contact the spacecraft. The chief scientist, Michael A'Hearn, thought the problem was like a "Y2K" issue. It might have been a computer clock problem that happened after a certain date.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Deep Impact (sonda espacial) para niños

In Spanish: Deep Impact (sonda espacial) para niños

- Double Asteroid Redirection Test – A similar mission that hit an asteroid to see how it would change its path.

- Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) – A satellite that hit Earth's Moon in 2009 to look for water.

- Hayabusa2

- Timeline of Solar System exploration

- List of minor planets and comets visited by spacecraft

- List of missions to minor planets

- List of missions to comets

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |