Diprotodon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids DiprotodonTemporal range: Pleistocene

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Infraclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Family: |

Diprotodontidae

|

| Genus: |

Diprotodon

Owen, 1838

|

Diprotodon was the biggest marsupial (like a kangaroo or koala) that ever lived. It roamed Australia from about 1.6 million years ago until it died out around 46,000 years ago. This means it lived through most of the Pleistocene Ice Age.

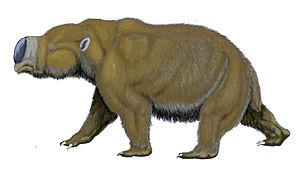

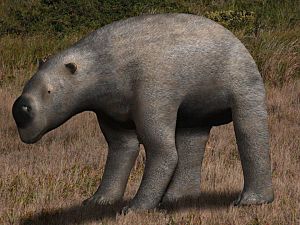

Imagine a rhino but without a horn – that's what Diprotodon looked like! Its feet pointed inwards, much like a wombat's. This gave it a "pigeon-toed" look. It had strong claws on its front feet. This suggests it might have dug up roots to eat. We know it had fur, like a horse, because footprints of its hairy feet have been found. Diprotodon fossils are found all over Australia, but not in Tasmania.

Scientists have even found female skeletons with baby bones where a pouch would have been. The largest Diprotodon were as big as a hippopotamus. They were about 3 meters (10 feet) long from nose to tail. They stood about 2 meters (6.5 feet) tall at the shoulder. They weighed around 2,790 kilograms (6,150 pounds).

Contents

Discovering the Giant Diprotodon

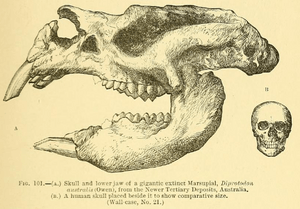

The first Diprotodon bones were found in the early 1830s. This happened in a cave near Wellington, in New South Wales. Major Thomas Mitchell discovered them. He sent the bones to England for study by Sir Richard Owen.

In the 1840s, Ludwig Leichhardt found many more Diprotodon bones. These were eroding from creek banks in the Darling Downs of Queensland. He told Owen the bones were so well preserved. He even thought living ones might be found in unexplored parts of Australia.

Most fossil finds show that Diprotodon often died during droughts. For example, hundreds of individuals were found in Lake Callabonna. Their lower bodies were well preserved, but their heads were crushed. Scientists think several family groups got stuck in mud while crossing a drying lake bed. Other finds show groups of young or old animals. These are usually the first to die during a drought.

In 2012, a large group of about 40 Diprotodon was found. This important discovery happened at Eulo, in South-West Queensland.

What Diprotodon Looked Like

Diprotodon looked a lot like a rhinoceros, but it didn't have a horn. Its feet turned inwards, similar to a wombat's. This made its walk appear "pigeon-toed." It had strong claws on its front feet. Its pouch, where it carried its young, opened backwards. Footprints show that its feet were covered in hair. This suggests it had a furry coat, much like a modern wombat.

For a long time, scientists weren't sure how many types of Diprotodon existed. Eight different species were described. However, many researchers believed there were only three at most. Some even thought there could be around twenty in total.

Recent studies compared the differences between all the described Diprotodon species. They looked at how much variation there is in a large living marsupial, the eastern grey kangaroo. They found the differences were similar. This suggested there were likely only two Diprotodon species, differing mainly in size. The smaller one was about half the size of the larger one.

However, both large and small Diprotodon lived at the same time. The size difference is similar to what we see in other marsupials where males and females are different sizes. For example, larger Diprotodon fossils often show signs of battle damage. This damage is common in competing males. The smaller ones do not show this. Also, their teeth were shaped the same, just different sizes. This is like kangaroos, where males and females have different tooth sizes but the same tooth shape. This evidence suggests that there was only one true species of Diprotodon. The size differences were simply between males and females.

Diprotodon Behavior

Since there was likely only one species with different-sized males and females, we can guess how they behaved. Animals over 5 kilograms (11 pounds) with different-sized sexes often have a specific breeding strategy. This is called polygynous breeding.

A good example of this today is how elephants live. Female elephants and their young form family groups. Lone males fight each other for the right to mate with all the females in a group. This behavior fits with what we find in Diprotodon fossils. Groups of adult and young fossils usually only contain adult female remains. This suggests the males lived separately or died in different places.

Why Diprotodon Disappeared

Most modern scientists believe Diprotodon and many other large Australian animals (called megafauna) died out shortly after humans arrived in Australia. This was about 50,000 years ago.

Some older researchers thought Diprotodon survived much longer. They believed it lived into the Holocene epoch (our current time). However, newer dating methods suggest these later dates were mistakes. They were likely caused by bones moving into newer layers of earth. Recent direct dating confirms that Diprotodon likely died out around 46,000 years ago.

Three main ideas try to explain why these giant marsupials disappeared.

Climate Change Theory

Australia has been getting drier over millions of years. This process started after it broke away from the supercontinent Gondwanaland about 40 million years ago. The recent ice ages brought long periods of cold and very dry weather to Australia. This dry weather during the last ice age might have killed off all the large Diprotodon.

However, there are problems with this idea. Diprotodon had already survived many similar ice ages before. Why would the most recent one be different? Also, the worst of the climate change happened 25,000 years after the extinctions. Finally, even during extreme weather, some parts of Australia stayed relatively wet and warm.

Human Hunting Theory

This idea suggests that early human hunters killed and ate Diprotodon, causing their extinction. The extinctions seem to have happened around the same time humans arrived in Australia. Diprotodon was one of the largest and least protected animals that died out.

Similar hunting-out events happened with large animals in New Zealand, Madagascar, and the Americas. Recent finds of Diprotodon bones show marks that look like butchering. This supports the hunting theory. Critics say there isn't much direct evidence of hunting in Australia, unlike other places. However, very detailed timelines of these changes support the idea that human hunting alone caused the megafauna to disappear.

Human Land Management Theory

The third idea is that humans indirectly caused the extinction. They did this by changing the ecosystem that Diprotodon depended on. Early Aboriginal people used fire regularly. They used it to drive animals, clear thick bushes, and create fresh new plant growth for food.

Evidence for this fire theory includes a sudden increase in ash deposits when people arrived in Australia. Also, early European settlers recorded how Aboriginal people managed land and hunted with fire. However, humans also caused megafauna to disappear in Tasmania without using fire to change the environment there. This makes some question the fire theory.

Many Causes Working Together

It's possible that all these ideas are true and worked together. For example, if humans burned a thick forest, it could become a more open, grassy area. This might not be good for a large animal that eats leaves and shoots. On the other hand, if the large plant-eating animals (like Diprotodon) disappeared, the undergrowth would grow very thick. When a natural fire eventually started, it would burn much more fiercely.

After a big fire, the area would be filled with plants that love fire, like eucalypt trees and many native grasses. These plants are not good food or habitat for large, slow-moving animals that eat leaves. Either way, the environment changed towards the modern Australian landscape. This landscape has highly flammable open forests and grasslands. These are not suitable for large, slow-moving plant-eating animals.

A study of swamp mud from Lynch's Crater in Queensland supports the hunting theory. It looked at fungal spores from megaherbivore dung over the last 130,000 years. It showed that the megafauna in that area almost completely disappeared about 41,000 years ago. At this time, climate changes were very small. The disappearance was followed by more charcoal (from fires) and a change from rainforest to fire-tolerant plants. This suggests that fires increased about a century after the large plant-eaters disappeared. This was probably because there was more fuel (plants) to burn. Grass increased over the next few centuries. This shows that human hunting was likely the main reason for the extinction.

See also

In Spanish: Diprotodon para niños

In Spanish: Diprotodon para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |