Don River (Ontario) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Don River |

|

|---|---|

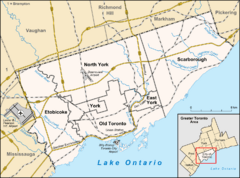

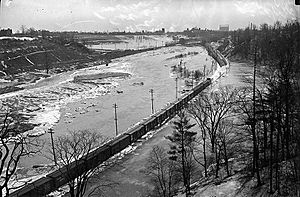

The Don River and the Don Valley Parkway

|

|

|

Location of the mouth of the Don River in Toronto

|

|

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Ontario |

| Cities | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source | Oak Ridges Moraine Ontario, Canada 43°59′20″N 79°23′57″W / 43.98889°N 79.39917°W |

| River mouth | Keating Channel Ontario, Canada 75 m (246 ft) 43°39′4″N 79°20′51″W / 43.65111°N 79.34750°W |

| Length | 38 km (24 mi) |

| Basin features | |

| Progression | Lake Ontario→ Saint Lawrence River→ Gulf of Saint Lawrence |

| River system | Lake Ontario drainage basin |

| Basin size | 360 km2 (140 sq mi) |

| Tributaries | |

The Don River (Ojibwe: Wonscotanach) is a river in southern Ontario, Canada. It flows into Lake Ontario at Toronto Harbour. The Don is one of the main rivers that drain the city of Toronto. Its source is in the Oak Ridges Moraine, a large ridge of hills north of the city.

The Don River is made up of two main parts: the East Branch and the West Branch. These two branches meet about 7 kilometres (4 mi) north of Lake Ontario. The area where they meet and flow south is called the lower Don. The areas above this meeting point are called the upper Don. A third important stream, Taylor-Massey Creek, also joins the Don River near this spot. The Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) helps manage the river and the land around it.

History of the Don River

Early Human Life Along the Don

People first came to the Don River area about 12,500 years ago. They were likely nomadic hunters, meaning they moved around to find food. Around 6,000 years ago, people started to build permanent homes. One important discovery, called the Withrow Site, was found in 1886 near Riverdale Park. It contained human remains and tools from about 5,000 years ago.

Around the 1300s, the Wendat people built villages along the river. They grew corn as a main food source. In the 1700s, the Mississaugas moved into the area. In 1787, the "Toronto Purchase" happened. The Mississaugas believed they were renting the land, not giving up their rights to it. But they ended up surrendering most of the land that would become Toronto to the British.

Naming the River

In 1788, a surveyor named Alexander Aitkin called the river Ne cheng qua kekonk. Elizabeth Simcoe, whose husband was Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe, wrote in her diary that another name used was Wonscotanach. This is an Anishnaabe phrase meaning "the river coming from the back burnt grounds." It might have referred to an old forest fire in the area. Lt. Gov. Simcoe named it the Don River because its wide valley reminded him of the River Don in Yorkshire, England.

Industrial Growth and Pollution

After the town of York (which became Toronto) was founded in 1793, many mills were built along the lower Don. One of the first was at Todmorden Mills. These mills made lumber, flour, and paper. By the 1850s, there were over 50 mills. The lower Don became a busy industrial area. Factories for storing oil and processing meat were built along the riverbanks. In 1879, the Don Valley Brick Works opened.

Waste from these factories and the growing city made the Don River and its marshy mouth very polluted.

Two hills north of Bloor Street were removed. Sugar Loaf Hill was taken down to build the Prince Edward Viaduct. Tumper's Hill was flattened in the 1960s to build the Don Valley Parkway.

In the 1880s, the lower part of the Don was straightened. It was put into a channel to create more space for boats and factories. This was called The Don Improvement Project. The idea was to send the polluted water into the Ashbridges Bay marsh. But this didn't work well. So, the river's mouth was turned west, leading into the inner harbour. This short extension is known as the Keating Channel.

In the early 1900s, the river and its valley were still neglected. Many sewage treatment plants were built along the river. Over 20 areas in the valley were used as landfills for garbage and factory waste. In 1917, the Don Destructor, a large incinerator, was built. It burned about 50,000 tonnes of trash every year for 52 years.

Efforts to Protect the Don

In 1946, a company planned to tear down old pioneer homes near Todmorden Mills. This made citizens angry, and they formed the Don Valley Conservation Association. This volunteer group successfully stopped the company's plan in 1947. The Association continued its work by planting trees, stopping people from picking wild flowers like trilliums, and preventing vandalism. They also held events to teach people about the Don Valley, including canoe trips up the river. The Association also pushed for new sewers to stop pollution from flowing into the Don.

After World War II, cities grew quickly in the northern parts of the river's watershed. At the same time, people became more interested in protecting nature. This led to the creation of conservation authorities in Ontario to manage rivers and their surrounding lands. The Don Valley Conservation Authority was formed in 1947. It had limited power and relied on local cities to pay for land purchases.

In 1954, Hurricane Hazel hit the Toronto area. While the Don Watershed received less rain than other areas, the hurricane showed how important it was to control flooding. In 1957, the Don Valley Conservation Authority and other groups became the Metro Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (MTRCA). Their job was to build flood control features and buy land in the valleys to prevent future disasters. This meant the MTRCA could stop new buildings in flood-prone areas. The MTRCA later became the TRCA in 1998.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, the Don Valley Parkway (DVP) was built through the lower Don Valley. This was a huge construction project. Homes, farms, and cottages in the valley were bought by the government. Two hills were leveled, and the soil was used to build the highway. Railways and the river were moved. The DVP helped commuters, but it also changed the valley a lot.

As more areas were developed, the natural spaces around the Don River shrank. This led to more pollution, heavy flooding, and muddy water. By the 1960s, the river was very neglected and polluted. In 1969, a group called Pollution Probe held a "Funeral for the Don" to show how bad the river's condition was.

Bringing the Don Back to Life

Efforts to clean up the Don gained strength in 1989. A public meeting led to the creation of the Task Force to Bring Back the Don. This group advises Toronto City Council. Their goal is to make the Don "clean, green, and accessible." Since then, they have organized garbage cleanups, tree plantings, and helped create or restore eight wetlands in the lower valley. One example is Chester Springs Marsh. Other groups, like Friends of the Don East, also became active. In 1995, the MTRCA created the Don Watershed Regeneration Council to help coordinate all these cleanup efforts.

In 1991, "Bring Back the Don" released a plan for restoration. It included creating a more natural mouth for the Don River. In 1998, a plan to improve Toronto's waterfront began, and a natural Don River mouth was a key part of it. A study for this project started in 2001. It also included plans to handle major floods, like one similar to Hurricane Hazel. In 2007, WaterfrontToronto held a design contest for the Don's mouth. The winning design was by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates. The project was planned to start in 2010, but it has been delayed due to a lack of money.

Thanks to the end of industrial pollution and the cleanup efforts, the river has improved a lot. Many types of fish have returned, and people can even fish there now.

Wonscotonach Parklands (Don River Valley Park)

In October 2016, the City of Toronto announced a new Don River Valley Park. This park will be 200 acres (81 ha) and stretch for 7 kilometres (4.3 mi). It will connect existing trails for biking and walking. The park also aims to restore the land and the upper parts of the Don River. In 2018, the park was renamed Wonscotonach Parklands. "Wonscotonach" is an Anishinaabe word meaning "black burnt grounds" or "area previously swept by fire."

Geography of the Don River

How the Valley Was Formed

The Don Valley is known for being very wide and deep in its lower parts. At the Bloor Street Viaduct, the valley is about 400 metres (1,300 ft) wide, but the river itself is only about 15 metres (49 ft) wide. This is because of how it was formed by glaciers.

The Don River and its deep valley were created about 12,000 years ago, at the end of the Wisconsinan Glaciation. During this time, all of Ontario was covered in ice. As the climate warmed, the glaciers melted. The melting ice created large amounts of water that carved out deep valleys over thousands of years. The Don River is now much smaller than the huge valley it created. It's called an underfit river because the valley is too big for the river that flows through it today.

The Don Valley is a good place to study the area's geological history. The Don Valley Brick Works was an old factory that dug up shale from a quarry. Geologists found nine different layers of rock there, showing the last three glaciations over 120,000 years.

Water Flow and Flooding

Because the land around the Don River is very urban, the river often has low water levels. But after heavy rain, the water level can rise very quickly, sometimes by 1–2 metres in just three hours. The average water flow for the Don River is about 4 m3/s. The highest flows happen in late February and late September.

When there are high flows during storms, the fast water can scour the bottom of the river. This makes it harder for fish to live there. Also, floodwaters carry a lot of mud and dirt from the surrounding land. This sediment collects in the Keating Channel, near the river's mouth. The TRCA has to dredge (remove) about 35,000 m3 of sediment each year, which weighs nearly 60,000 tonnes (59,000 long tons; 66,000 short tons).

River's Path and Smaller Streams

The east branch of the Don, also called the Little Don River, starts at the southern edge of the Oak Ridges Moraine. It flows southeast through forests in Richmond Hill, Thornhill, and east of Willowdale and Don Mills.

Another part of the eastern Don, called German Mills Creek, flows next to the main eastern branch. It joins the main branch at Steeles Avenue, which is the northern border of Toronto. South of Lawrence Avenue, the river flows through the Charles Sauriol Conservation Reserve. This area is mostly undeveloped parkland. Charles Sauriol was a famous protector of the Don.

The western branch starts near Maple, Ontario. It flows southeast through the industrial areas of Concord and the G. Ross Lord Reservoir. It crosses Yonge Street and flows through Hoggs Hollow, past York University's Glendon campus. Then it continues to Leaside, Flemingdon Park, and Thorncliffe Park before joining the eastern branch.

Many parts of the western branch and Taylor-Massey Creek are surrounded by parkland. As old factories and railway lines have moved, more space has opened up. This space is now being turned into bicycling trails. These paved trails now stretch from Lake Ontario northward in several directions, offering about 30 km of off-road paths.

Downstream from where the branches meet, the river flows through a wooded area called Crothers Woods. This area is special because it has a high-quality beech-maple forest on its slopes. South of Pottery Road, the river enters a more changed section. It then flows into a straightened part with concrete and steel walls, left over from the industrial era. From there, the river flows into the Keating Channel at Lake Shore Boulevard East, which is at the northeast corner of the Toronto Harbour.

To control flooding from the Don River, Waterfront Toronto is working on the Port Lands Flood Protection Project. This project will extend the river south past the Keating Channel and then west to a new mouth at Toronto Harbour. This new, man-made river section will be a naturalized valley with new parkland. After this is built, water will flow into the Keating Channel from the Don River only during high floods. A new piece of land, Villiers Island, will also be created.

Cleanup Efforts

In the 1880s, sewers were built through the Don Valley to carry away sewage and factory waste. This caused a lot of pollution and bad smells until the late 1950s. Since then, things have slowly improved. The city has installed tanks to store wastewater, asked homeowners to disconnect their downspouts (which send rainwater into sewers), and cleaned streets to stop pollution from flowing into the river. By 1979, the lower Don showed improvements in oxygen levels, phosphates, and suspended solids. However, by 2021, Taylor-Massey Creek, a tributary, had not improved much.

As of As of 2021[update], the Don River still gets polluted by sewage during heavy rainfalls. This happens when storm sewers, which carry both rainwater and sewage, overflow into the river. To fix this, the city is spending $3 billion to build three tunnels. These tunnels will be 22 kilometres (14 mi) long and will divert sewage away from the river to the Ashbridges Bay Treatment Plant. The project started in 2018 and is expected to be finished by 2038. As of As of 2021[update], a tunnel boring machine has completed about half of the 10.4-kilometre (6.5 mi) Coxwell Bypass tunnel, which is 50 metres (160 ft) underground.

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |