Elisabeth Dieudonné Vincent facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Elisabeth Dieudonné Vincent

|

|

|---|---|

Vincent

|

|

| Born |

Elizabeth Dieudonné

1798 |

| Died | 1883 (aged 84–85) Antwerp, Belgium

|

| Nationality | French |

| Other names | Élisabeth Dieudonné, Élisabeth Dieudonné Tinchant, Elisabeth Vincent, Elizabeth Dieudonné Vincent, Elizabeth Tinchant |

Elisabeth Dieudonné Vincent (1798-1883) was a Saint Dominican Creole woman. She was a businesswoman and moved between countries. Born in 1798 in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), her mother was a free woman of color and her father was French.

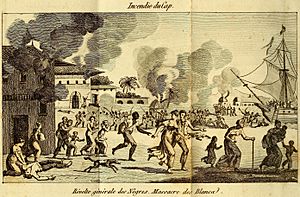

Even though her parents were not officially married, her father recognized her as his child. In 1803, her family escaped the violence of the Haitian Revolution. They moved to Santiago de Cuba, where they got papers to prove they were free. In 1809, Spanish officials made French colonists leave because of a war in Europe. So, Elisabeth moved to New Orleans in Louisiana.

Vincent married Jacques Tinchant in 1822. They ran a business in New Orleans. They also earned money by renting out enslaved people they owned. In 1835, she changed her marriage record to add a last name. This helped her avoid the challenges of being born outside of marriage and having enslaved ancestors.

Life became harder in the United States due to strict Black Codes. These laws limited the rights of people of color. So, Elisabeth and her family moved to France. There, they ran a dairy farm and vineyards in Gan. Bad economic times and violence during the French Revolution of 1848 made them move again. In 1857, they went to Antwerp, Belgium. They invested in their sons' new tobacco business there.

Contents

Early Life and Family History

Elisabeth Dieudonné was born in 1798 in Jérémie, Saint-Domingue. Her mother, Rosalie, was a former enslaved woman from the Poulard nation. Her father was Michel Étienne Henry Vincent, a Frenchman. He once had a special right to sell meat in Les Cayes.

Elisabeth was baptized in Cap-Dame-Marie. Her parents were not married, but her father accepted her as his daughter. Rosalie, Elisabeth's mother, came from an area in West Africa. This area included parts of modern-day Mali and Guinea. She arrived in Saint-Domingue just before the Haitian Revolution.

Enslaved people from Senegambia were not common in Saint-Domingue. Records show that Rosalie was owned by a freedman named Alexis Couba in the early 1790s. He sold her to a merchant named Marthe Guillaume. In 1793, Guillaume sold Rosalie to a butcher. But within two years, she was back with Guillaume.

In December 1795, Guillaume gave Rosalie her freedom. This is called manumission. However, the British governor Adam Williamson would not approve the official papers. This happened during the British occupation of Haiti.

Rosalie was technically free but had no official papers. Her status was unclear until the British left in 1798. The next year, she was listed in baptism records as "Marie Françoise, called Rosalie, free black woman." She had her daughter Elisabeth baptized as a free-born child.

By 1802, France had brought back slavery in Martinique. There were rumors it would happen in Saint-Domingue too. To protect his family, Michel Vincent wrote a document in 1803. It said Rosalie and her children were his enslaved people and he was freeing them.

Within months, French troops attacked Jérémie. Rosalie, Michel, and Elisabeth fled to nearby Santiago de Cuba. It is not known what happened to the other three children.

Life in Cuba and New Orleans

About 18,000 other refugees arrived in Santiago de Cuba. Michel started working as a farrier (a person who shoes horses). Rosalie raised farm animals. There were no French officials on the island. So, a special agency helped French refugees with legal matters.

On March 14, 1804, Michel Vincent, who was sick, filed his last will. Three days later, Rosalie paid the agency to register the freedom document. This was the document Michel had prepared before they left Saint-Domingue. Michel died within days. His property was sold to pay his debts.

Moving to New Orleans

In 1809, during a war in Europe, the governor of Cuba told all French refugees to leave. Rosalie went back to independent Haiti. Elisabeth traveled with her godmother, Marie Blanche Peillon, and her partner, Jean Lambert Détry. They went to New Orleans.

Peillon and Détry bought land in Faubourg Marigny. They started businesses. Détry worked as a contractor. Peillon bought and sold land and enslaved people. When Détry died in 1821, he left Elisabeth $500. She decided to get married.

Elisabeth prepared a marriage contract with Jacques Tinchant. He was the son of Suzette Bayot, another free woman of color from Saint-Domingue. The contract did not include a last name for Elisabeth. It listed her as Marie Dieudonné.

The couple married in 1822. Tinchant worked as a builder and carpenter. To earn money, they also rented out enslaved people. These included Gertrude and her daughter Marie Louise. They were a wedding gift from Peillon.

The couple lived with Peillon, but it was difficult. She was controlling and liked to argue. She refused to give Elisabeth her inheritance from Détry. After a year, the couple moved out. On January 1, 1825, they baptized their first child, François Louis Tinchant. This happened at the St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans. He was recorded as a free child.

That year, new laws were passed. They stopped interracial marriage. More laws were passed in Louisiana to limit the freedom of people of color. Elisabeth and Jacques had more children: Joseph (born 1827), Pierre (born 1833), Jules (born 1836), and Ernest (born 1839). In 1833, they gave Gertrude her freedom. They then acquired another enslaved person named Giles.

By 1835, Tinchant and his half-brother, Pierre Duhart, started a company. They developed land and built houses to sell. In November, Elisabeth wanted to remove the challenges of being born outside of marriage and having enslaved ancestors. She asked a notary to change her name on the marriage record to Elisabeth Vincent.

They showed a copy of Elisabeth's baptism certificate. Her mother likely brought this during a visit in April. Her father's recognition of her did not officially give her the right to use his last name. But the notary, who knew Tinchant well, agreed to change the record.

Over the next few years, laws in Louisiana became even stricter for free people of color. This included limits on schooling. They also had to register every year to prove they were free. Many of Tinchant's family members left Louisiana for France. Elisabeth and Jacques followed them in 1840. They sold Marie Louise to Gertrude for $800.

Life in France

In 1840, Elisabeth and Jacques moved to the Basses Pyrenees region of France. Their oldest son, Louis, stayed in New Orleans. Tinchant's brother, Pierre Duhart, and his parents were already living there. They bought a farmhouse with furniture, 21 hectares (52 acres) of land, two barns, and farm animals. This was in Gan and cost 27,000 francs.

Gan had an elementary school. But Tinchant and Vincent sent their children to a better school in Pau. Soon after they arrived, Tinchant's mother died. The next year, they had their last child, Edouard (born 1841). Even though he was born in France, he was not a French citizen. This was because his father was American-born and his mother lost her nationality when she married. However, the couple registered his birth.

The couple had no farming experience. So, they hired sharecroppers to work their dairy, grain fields, and vineyards. Poor harvests, strict government rules, and bad economic conditions led to new ideas spreading. These were republican ideals.

In 1848, there was growing opposition to France's monarchy. This led to unrest in Pau, where all their sons were in school. In 1851, Louis-Napoleon took control of the government. This moved the country away from republican ideas.

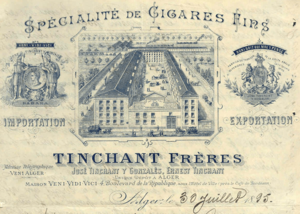

The children stayed in school until 1854. But the family started planning to leave. They sold their farm for less than they paid for it. They moved temporarily to Jurançon. The money from the farm was loaned to their two oldest sons, Louis and Joseph. They started a cigar making business in New Orleans. The brothers wanted a European trading partner. They chose Belgium because it did not have a government monopoly on tobacco.

Life in Belgium

In 1857, the family moved to Antwerp, Belgium. Tinchant and Louis worked to open a cigar store and factory. They called it Maison Américaine. One by one, the brothers went to the United States. They built a successful international tobacco business. Joseph was in New Orleans, Pierre worked along the Gulf Coast, and Edouard settled in Mobile, Alabama. Jules worked from Veracruz, Mexico, and Ernest stayed in Antwerp.

Tinchant died in 1871. Elisabeth Vincent lived for over ten more years. She died in Antwerp on November 29, 1883. She and Tinchant were buried in the Schoonselhof cemetery. Three generations of their family are buried there.

Family Legacy

Vincent's sons Joseph and Edouard both served in the 6th Louisiana Regiment of the Union Army. This was during the American Civil War. After the war, Edouard was a delegate to the Louisiana Constitutional Convention of 1867. He suggested that women should have equal civil rights, regardless of their race.

Three generations of the family worked in the tobacco business. But the business finally closed because of problems from World War II. Several family members fought in the resistance during the war. Joseph's granddaughter died in a Ravensbrück concentration camp. She was sent there for her political activities.

The story of Vincent and her family helps us understand history. It shows how legal status and paperwork affected people of color. Being able to read and understanding the importance of documents was key to her family's freedom. Even with political unrest during her life, the family managed to deal with different racial divides and legal systems.

According to historian Afua Cooper, Vincent's story shows that black and free people of color could find success and freedom. They could gain respect and security across many countries in the 1800s. Historian James Sidbury says that Vincent's family history helps us understand the complex experiences of the African diaspora. The many documents about Vincent show that their stories are not just oral histories.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |