Elizabeth Rona facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Elizabeth Rona

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Erzsébet Róna

20 March 1890 |

| Died | 27 July 1981 (aged 91) |

| Nationality | Hungarian Naturalized American citizen, 1948 |

| Other names | Elisabeth Róna |

| Occupation | Nuclear chemist |

| Years active | 1914–1976 |

| Known for | Polonium extraction and investigating radioactivity in sea water |

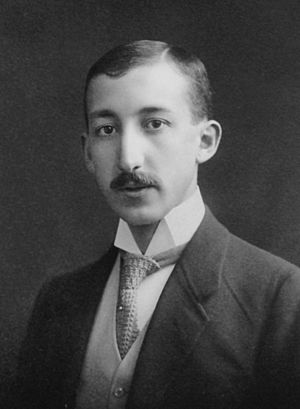

Elizabeth Rona (born March 20, 1890 – died July 27, 1981) was a brilliant Hungarian nuclear chemist. She was famous for her work with radioactive isotopes, which are special types of atoms that give off energy.

Elizabeth Rona became known around the world for creating a better way to prepare samples of polonium, a radioactive element. She was seen as a top expert in separating isotopes and preparing polonium. Between 1914 and 1918, she developed a theory that showed how fast a substance spreads depends on the weight of its nucleus. She also confirmed the existence of "Uranium-Y," which we now call thorium-231. This was a big step forward in nuclear chemistry. In 1933, she won the Haitinger Prize from the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

After moving to the United States in 1941, she continued her research. She shared her special methods for extracting polonium with the Manhattan Project, a secret wartime effort. Later, she became a professor of nuclear chemistry at the Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies. After 15 years, she moved to the Institute of Marine Sciences at the University of Miami. At both places, she kept studying how old seabed elements were and how to use radiometric dating to find their age. In 2015, she was honored by being added to the Tennessee Women's Hall of Fame.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Elizabeth Rona was born in Budapest, Hungary, on March 20, 1890. Her father, Samuel Róna, was a successful doctor who helped bring new X-ray and radium therapies to Budapest. Elizabeth wanted to follow in his footsteps and become a doctor too. However, her father thought it would be too hard for a woman. Even though he passed away when she was in her second year of university, her father had always encouraged her love for science.

She studied chemistry, geochemistry, and physics at the University of Budapest. She earned her PhD in 1912.

Starting Her Career in Science

After getting her PhD, Elizabeth Rona began her advanced training in 1912. She worked in Berlin, studying yeast. In 1913, she moved to Karlsruhe University to work with Kazimierz Fajans, who discovered isotopes.

In the summer of 1914, she studied in London. But when World War I began, she returned to Budapest. She took a job at Budapest's Chemical Institute. There, she wrote a paper about how radon spreads in water. She also worked with George de Hevesy to confirm a new element called Uranium-Y, which is now known as Th-231. Other scientists had tried and failed to confirm it. But Rona was able to separate it and prove it was a beta emitter (meaning it gives off beta particles) with a half-life of 25 hours. The Hungarian Academy of Sciences published her important findings.

During this work, Rona was the first to use the ideas of "isotope labels" and "tracers." She noticed that how fast something spreads depends on the weight of its atomic parts. This idea later helped other scientists develop tools like the mass spectrograph. Besides her scientific skills, Rona could speak English, French, German, and Hungarian.

When George de Hevesy left Budapest in 1918, Franz Tangl, a well-known biochemist, offered Rona a teaching job at the University of Budapest. She taught chemistry to students who needed extra help. This made her the first woman to teach chemistry at a university in Hungary.

In 1919, political problems in Hungary made Rona's work difficult. In 1921, Otto Hahn invited her to join his team in Berlin at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. She worked there to separate ionium (now Th-230) from uranium. Because of economic problems in Germany, she had to move to a different part of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute that focused on practical research.

In 1923, she returned to Hungary and worked in a textile factory, but she didn't like it. So, in 1924, Stefan Meyer asked her to join the Institute for Radium Research in Vienna. There, she studied hydrogen rays and worked on using polonium as a radioactive material instead of radium.

Work in Austria

In 1926, Stefan Meyer suggested that Rona work with Irène Joliot-Curie in Paris to learn how to make polonium samples. Rona went to the Curie Institute in Paris and developed a much better way to prepare polonium. This method produced strong alpha-emissions (another type of radiation). She became known as an expert in this field. She brought these skills and a small disc of polonium back to the Radium Institute in Vienna. This disc allowed the Institute to create its own polonium samples for research.

Her skills were in high demand, and she worked with many other scientists in Vienna. She worked with Marietta Blau on photographic plates for hydrogen rays and with Hans Pettersson. In 1928, Pettersson asked her to test a sample of sea bottom mud to find out how much radium it contained. She took the samples to a clean oceanographic lab in Sweden, which became her summer research spot for the next 12 years.

With Berta Karlik, she studied the half-lives (how long it takes for half of a radioactive substance to decay) of uranium, thorium, and actinium. This work helped develop radiometric dating, a way to figure out the age of rocks and other materials. In 1933, Rona and Karlik won the Haitinger Prize from the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

In 1934, Rona returned to Paris to study with Joliot-Curie, who had discovered artificial radioactivity. After Curie's death and Rona's own illness, she returned to Vienna. She shared what she learned with a group of researchers. They studied how bombarding radioactive atoms with neutrons affected them. For several years, the group also worked on whether the depth of ocean water affected its radium content. They studied elements in seawater from different places.

After Austria was taken over in 1938, Rona and Marietta Blau had to leave the Radium Institute because they were Jewish. Rona first went back to Budapest and worked in a factory lab, but that job ended quickly. She then worked in Sweden and later took a temporary job at the University of Oslo in Norway. Even though she didn't want to leave her home, she returned to Hungary after a year. She then worked at the Radium-Cancer Hospital in Budapest, preparing radium for medicine.

Moving to the United States

In early 1941, with war dangers growing, Elizabeth Rona got a visitor's visa and moved to the United States. For three months, she couldn't find a job and was even suspected of being a spy. She reached out to scientists she knew in Europe for help. At a meeting, she met physicist Karl Herzfeld, who helped her get a teaching job at Trinity College in Washington, D.C.

During this time, she received a special grant to do research at the Geophysical Laboratory. She analyzed seawater and sediments. From 1941 to 1942, she worked with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, measuring radium in seawater and river water. Her study in 1942 showed that seawater had less radium compared to uranium, while river water had more.

Later, Rona received a secret message about war work involving polonium. Brian O'Brien visited her and explained the confidential work for the Manhattan Project. This project was a top-secret effort to build the first atomic bomb. They wanted to use her method for extracting polonium. Polonium, combined with beryllium, was needed to create a reaction that would start the atomic fission (splitting of atoms) for the bomb. Rona shared her methods without being paid. Plants were built in New Mexico based on her ideas for processing the element, but Rona was not given any details about the bomb itself.

Rona's methods were also used in experiments to study how radiation affects people. Early in her career, she had learned about the dangers of radium. Her boss, Stefan Meyer, didn't think the dangers were serious, but Rona bought her own protective gear. When vials of radioactive material exploded in the lab, she believed her mask saved her. Another scientist, Ellen Gleditsch, had also warned her about the risks of radium, especially after Joliot-Curie died from radiation-related illness. In her 1978 book, Rona wrote about the harm to bones, hands, and lungs of scientists who studied radioactivity. She noted that their fingers were often damaged because they didn't wear gloves and poured substances without protection.

Later Career and Legacy

Elizabeth Rona continued teaching at Trinity College until 1946. In 1947, she started working at the Argonne National Laboratory. There, she focused on ion exchange reactions and published several papers for the United States Atomic Energy Commission. In 1948, she became a citizen of the U.S.

In 1950, she began research at the Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies. She worked with Texas A&M University on dating seabed sediments by looking at their radioactive decay. She retired from Oak Ridge in 1965. Then, she went to work at the University of Miami, teaching at the Institute of Marine Sciences for ten years. Rona retired for a second time in 1976. She moved back to Tennessee in the late 1970s and published a book in 1978 about her methods using radioactive tracers.

Elizabeth Rona passed away on July 27, 1981, in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

Rona did not always receive full credit for her amazing work during her lifetime. However, she was honored after her death. In 2015, she was added to the Tennessee Women's Hall of Fame. In 2019, The New York Times finally published an obituary for her as part of their "Overlooked (obituary feature)" series, which highlights important people whose deaths were not reported at the time.

Selected Works

See also

In Spanish: Elizabeth Rona para niños

In Spanish: Elizabeth Rona para niños

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |