Elizebeth Smith Friedman facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

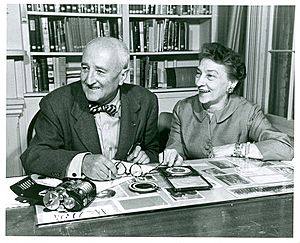

Elizebeth Smith Friedman

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Elizebeth Smith

August 26, 1892 Huntington, Indiana U.S.

|

| Died | October 31, 1980 (aged 88) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Cryptanalyst |

| Years active | 1916–1971 |

| Known for | "America's first female cryptanalyst" |

| Spouse(s) | William F. Friedman |

| Children | 2 |

Elizebeth Smith Friedman (born August 26, 1892 – died October 31, 1980) was an American code-breaker and writer. She was famous for solving secret enemy codes during both World Wars. She also helped stop international smuggling during a time called Prohibition. This was when alcohol was illegal in the U.S.

Elizebeth worked for many U.S. government groups. These included the Treasury, Coast Guard, Navy, and Army. She was known as "America's first female cryptanalyst." A cryptanalyst is someone who breaks codes.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Elizebeth Smith was born in Huntington, Indiana. Her father, John Marion Smith, was a Quaker and a banker. Her mother was Sophia Smith. Elizebeth was the youngest of nine children. She grew up on a farm.

From 1911 to 1913, Elizebeth went to Wooster College in Ohio. She left when her mother became sick. In 1913, she moved to Hillsdale College in Michigan. This college was closer to her home.

In 1915, she finished college with a degree in English literature. She loved languages and also studied Latin, Greek, and German. She was one of only two children in her family to go to college. Later, in 1938, Hillsdale College gave her an special law degree.

After college, in 1915, Elizebeth worked as a substitute principal. This was at a high school in Wabash, Indiana. But she left this job in 1916 and moved back home.

Amazing Career in Code-Breaking

Riverbank Laboratories and World War I

Elizebeth Smith started working at Riverbank Laboratories in Geneva, Illinois, in 1916. This was one of the first places in the U.S. to study secret codes. Colonel George Fabyan, a rich businessman, owned Riverbank Laboratories. He was very interested in Shakespeare.

Elizebeth was looking for a job. She visited a library in Chicago. A librarian there knew about Fabyan's interests. The librarian called Fabyan, who invited Elizebeth to his large estate. There, they talked about her working for him. Her job would be to help prove that Sir Francis Bacon had secretly written Shakespeare's plays. This work involved trying to find hidden messages in the plays and poems.

At Riverbank, Elizebeth met William F. Friedman. He was a plant biologist who also worked on the Bacon-Shakespeare project. They got married in May 1917.

Riverbank collected old information about secret writing. After the Civil War, not many people in the U.S. knew about military codes. Elizebeth and William Friedman were two of the few who did. When the U.S. joined World War I, Fabyan started a new code department at Riverbank. The Friedmans were in charge. They offered their help to the government.

During the war, the Friedmans created many ideas for modern code-breaking. Several U.S. government groups asked Riverbank for help. They also sent people there for training. The Friedmans worked together for four years. Their lab was the only place in the country focused on codes. In 1921, the Friedmans left Riverbank. They went to work for the War Department in Washington, D.C..

Fighting Smugglers During Prohibition

In 1919, a law called the National Prohibition Act made it illegal to make, sell, or trade alcohol in the U.S. This time, from 1920 to 1933, was called Prohibition. But people still wanted alcohol. So, smugglers illegally brought alcohol into the country. They also smuggled other expensive items like perfume and jewels.

These smugglers used secret radio messages to plan their operations. The Coast Guard was in charge of stopping them. They hired Elizebeth Friedman in 1922 to decode these messages. She had left her previous job.

Elizebeth and a small team she trained led the fight against international smuggling. At first, the smugglers' codes were simple. But they soon became more complex. This did not stop Elizebeth. She successfully broke many types of codes. These included simple substitution codes and more complex ones.

From 1927 to 1939, Elizebeth's unit worked with the U.S. Treasury Department. They watched for smuggling and crime. Elizebeth herself solved most of the secret messages. In 1928, she taught another agent, C.A. Housel, how to decode messages. He then decoded 3,300 messages in 21 months. In 1929, she went to Houston, Texas. There, she solved 650 smuggling cases. She broke 24 different coding systems used by the smugglers. Her work helped to convict criminals like the Ezra Brothers.

Elizebeth Friedman solved over 12,000 coded messages by hand in three years. This led to 650 criminal cases. She even helped to catch famous criminals like Al Capone.

In 1930, Elizebeth suggested creating a team to handle the growing number of messages. Her idea was approved in 1931. She became the head of the only code-breaking unit in America led by a woman. She hired and trained the analysts. By 1932, her team was the best in the country. This allowed them to break new and unusual codes quickly. Elizebeth always stayed ahead of the smugglers. Her successes led to many people being found guilty of breaking the Prohibition law.

Elizebeth also often spoke in court cases against accused smugglers. She was an expert witness in 33 cases. Newspapers and magazines wrote about her, making her famous. Her decoded messages helped to link smugglers to their ships. She testified in Texas and New Orleans, Louisiana. In 1933, her testimony helped convict five leaders of a smuggling group.

The next year, she helped settle a disagreement between Canada and the U.S. This was about a ship called I'm Alone. The ship was flying the Canadian flag. It was sunk by a U.S. Coast Guard ship. Canada asked the U.S. for a lot of money. But Elizebeth decoded 23 messages. These messages showed that the ship was actually owned by U.S. citizens. Most of Canada's claim was then dismissed.

In 1937, the Canadian government asked for Elizebeth's help. She testified in a trial involving Gordon Lim and others. She broke a very complex Chinese code, even though she didn't know the language. This was key to the successful convictions.

Code-Breaking During World War II

During World War II, Elizebeth's Coast Guard unit joined the Navy. They became the main U.S. source of information about Operation Bolívar. This was a secret German spy network in South America. Before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, there was worry that Germany might attack the U.S. through Latin America. The FBI was in charge of stopping this threat. But Elizebeth's team was the only U.S. group with experience in finding spy messages.

Elizebeth’s team remained the main U.S. code-breakers for the South American threat. They solved many secret codes used by the Germans and their supporters. This included three different Enigma machines. The U.S. and British code-breaking centers shared their solutions. Elizebeth's team and a British team both solved the Enigma machines around the same time. Two of these machines were used by Johannes Siegfried Becker, a top German agent.

Biographer Jason Fagone said, "Elizebeth was his nemesis." This means she was his biggest enemy. She successfully tracked him when other agencies failed. After the spy ring was broken, countries like Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile joined the Allies.

During the war, Elizebeth’s team decoded 4,000 messages. These messages were sent on 48 different radio channels. Elizebeth's unit often helped the FBI. But their work was not always given credit. Elizebeth was annoyed by the FBI's mistakes. For example, they sometimes arrested spies too quickly. This let the Nazis know their codes were broken. After World War II, the FBI claimed they led the code-breaking effort. They did not mention Elizebeth or the Coast Guard.

In 1944, Elizebeth helped convict Velvalee Dickinson. Dickinson was known as the "Doll Woman." She used her antique doll shop as a cover. She sent secret messages to Japanese agents. These messages contained coded information about naval ships in Pearl Harbor. Elizebeth decoded these messages. This helped to convict Dickinson.

After World War II, Elizebeth became a helper for the International Monetary Fund. She created secure communication systems for them.

Retirement and Legacy

After leaving government service, Elizebeth and her husband worked on a book. They both loved Shakespeare. Their book was called The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined. It won awards. In this book, the Friedmans showed that claims about Francis Bacon writing Shakespeare's plays were wrong. They did this with great skill.

The earlier work at Riverbank Laboratories had tried to prove Bacon wrote Shakespeare. It claimed Bacon used a secret code in the original Shakespeare books. But the Friedmans, in their own book, hid a secret Baconian code. It was an italicized phrase that said, "I did not write the plays. F. Bacon." Their book is seen as the most important work on this topic. It's interesting that the Bacon-Shakespeare project was how the Friedmans first got into code-breaking.

After her husband died in 1969, Elizebeth spent her time collecting his work. This collection of code-breaking materials was given to the George C. Marshall Research Library. In 1971, she also gave her own papers to the library.

Elizebeth was part of groups like the League of Women Voters. She also worked to make the District of Columbia a state. She was a respected public speaker.

Personal Life

Elizebeth's name is spelled in a rare way. Her mother spelled it "Elizebeth" because she did not want her daughter to be called "Eliza."

In 1917, she married William F. Friedman. He later became a famous code-breaker. Elizebeth was the one who introduced him to the field of code-breaking.

They had two children: Barbara Friedman Atchison (born 1923) and John Ramsay Friedman (born 1926).

In the 1930s, William Friedman began to face health challenges. Elizebeth supported him and helped him through these times. After the war, Elizebeth spent more and more time caring for her husband. He passed away on November 2, 1969.

Elizebeth Friedman died on October 31, 1980, in Plainfield, New Jersey. She was 88 years old. She was cremated, and her ashes were spread over her husband's grave. This was at Arlington National Cemetery.

Special Recognition

Elizebeth Friedman's amazing work became more known after she died. She had promised the U.S. Navy to keep her World War II role a secret. She kept this promise until her death. Her documents were not made public until 2008.

- In 1999, she was added to the NSA Hall of Honor. This is a special place for important people in code-breaking.

- The NSA auditorium, named after William in 1975, was renamed in 1999. It became the "William and Elizebeth Friedman Auditorium."

- In 2002, an NSA building was named the William and Elizebeth Friedman Building.

- On June 17, 2014, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms named its main auditorium after her.

- In 2017, Jason Fagone wrote a book about her life. It was called The Woman Who Smashed Codes.

- In April 2019, the U.S. Senate honored her life and legacy.

- On July 7, 2020, the U.S. Coast Guard announced they would name a new ship after her. It will be the USCGC Friedman (WMSL-760).

- The Codebreaker, a TV show about her life, came out on January 11, 2021.

- In October 2021, Amy Butler Greenfield published her book, The Woman All Spies Fear.

Works and Publications

- Friedman, William F. and Friedman, Elizebeth Smith Methods for the Reconstruction of Primary Alphabets, Riverbank Publication Number 21, 1917

See also

- Cryptography

- Edward Isaac Ezra

- Velvalee Dickinson