F. C. S. Schiller facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

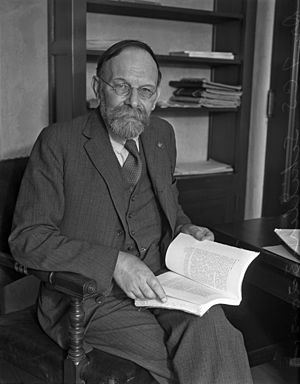

F. C. S. Schiller

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Ferdinand Canning Scott Schiller

16 August 1864 Ottensen near Altona, Holstein, German Confederation

|

| Died | 6 August 1937 (aged 72) Los Angeles

|

| Education | Rugby School Balliol College, Oxford (B.A., 1887) |

| Era | 19th/20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | British pragmatism |

| Institutions | Corpus Christi College, Oxford |

|

Main interests

|

Pragmatism, logic, Ordinary language philosophy, epistemology, eugenics, meaning, personalism |

|

Notable ideas

|

Criticism of formal logic, justification of axioms as hypotheses (a form of pragmatism), intelligent design, eugenics |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Ferdinand Canning Scott Schiller (16 August 1864 – 6 August 1937), often called F. C. S. Schiller, was a German-British philosopher. He was born in Altona, a place that was part of the German Confederation at the time. Schiller studied at the University of Oxford and later became a professor there. He also taught at Cornell University and the University of Southern California. During his life, he was a well-known philosopher.

Schiller's ideas were very similar to pragmatism, a philosophy developed by William James. However, Schiller preferred to call his own ideas "humanism". He strongly disagreed with other philosophical ideas like logical positivism (supported by philosophers like Bertrand Russell) and absolute idealism (like the ideas of F. H. Bradley).

Schiller was also an early supporter of evolution. He was a founding member of the English Eugenics Society, which was a group interested in improving human qualities through controlled breeding.

Contents

Life and Career

Ferdinand Canning Scott Schiller was born in 1864. His family home was in Switzerland, but he grew up in Rugby, England. He went to Rugby School and then Balliol College, Oxford. He did very well in his studies, especially in German.

His first book, Riddles of the Sphinx (1891), was a success. He used a fake name for it because he was worried about how people would react to his ideas. From 1893 to 1897, he taught philosophy at Cornell University in the United States.

In 1897, Schiller returned to Oxford. He became a fellow and tutor at Corpus Christi for over thirty years. He was also the president of the Aristotelian Society in 1921. In 1926, he became a fellow of the British Academy.

Later in his career, in 1929, he became a visiting professor at the University of Southern California. He spent half of each year in the U.S. and half in England. Schiller passed away in Los Angeles in August 1937 after a long illness.

Schiller was a founding member of the English Eugenics Society. He wrote three books about eugenics: Tantalus or the Future of Man (1924), Eugenics and Politics (1926), and Social Decay and Eugenic Reform (1932).

Schiller's Philosophy

F.C.S. Schiller first shared his philosophical ideas in 1891. He was worried that his ideas, which explored big questions about existence, might harm his career. At the time, many thinkers focused only on what could be proven by science.

However, Schiller was not against science. He wanted to find a middle ground. He believed that focusing only on science (which he called "naturalism" or "positivism") ignored deeper questions. But he also thought that focusing too much on abstract, disconnected ideas (which he called "abstract metaphysics") made philosophy lose touch with real life.

Schiller argued that both these extreme ways of thinking had problems.

- Naturalism couldn't explain "higher" parts of human life, like freewill, consciousness, or purpose. It focused only on physical things.

- Abstract metaphysics created grand, imaginary worlds that didn't help us understand our everyday lives. It ignored things like change and physical reality.

Schiller believed that for us to have knowledge and make moral choices, both the "lower" (physical, changing) and "higher" (purpose, ideas) parts of the world must be real. This led him to develop what he first called "concrete metaphysics" and later "humanism."

Humanism and Pragmatism

After publishing his first book, Schiller discovered the work of William James, a pragmatist philosopher. This greatly influenced Schiller. For a while, Schiller focused on expanding James's ideas, calling his own version "humanism."

In one important essay, "Axioms as Postulates" (1903), Schiller took James's idea of the "will to believe" even further. He suggested that we accept basic rules, or "axioms," not because they are proven, but because we need them to make sense of the world. For example, we believe in cause and effect because it helps us live, not because we can perfectly prove it.

Later in his career, Schiller's ideas became more distinct from James's. He focused on criticizing formal logic. Formal logic looks at the structure of an argument to decide if it's correct. But Schiller argued that you can't decide if an argument is valid just by its form. You need to know the context and purpose of the argument.

For example, if someone says, "All salt is soluble in water," and "Cerebos is not soluble in water, so Cerebos is not a salt."

- In a cooking context, Cerebos is salt.

- In a chemistry context, Cerebos is not salt (because it has other ingredients).

Schiller said that without knowing the purpose (cooking or chemistry), you can't truly judge the argument. He believed that the meaning and truth of statements depend on how they are used in real-life situations.

Why Schiller Disagreed with Other Philosophies

Schiller believed that both "abstract metaphysics" and "naturalism" failed to give humans a meaningful place in the world.

- Abstract Metaphysics: Schiller argued that philosophers like Hegel created systems of thought that were too far removed from reality. These systems focused on "eternal truths" that didn't change. But Schiller said that life is full of change and individual experiences. If a philosophy ignores change, it can't help us understand our moral actions or our lives. He felt these systems made our real, imperfect lives seem unimportant.

- Naturalism: Schiller also criticized naturalism, which tries to explain everything using only physical science. He argued that naturalism couldn't explain "higher" things like consciousness, free will, or meaning. It couldn't reduce these complex human experiences to just atoms or brain activity. He said that while humans are made of matter, we are also much more.

Schiller believed that naturalism, by denying the reality of these "higher" elements, led to scepticism (doubting everything) about knowledge and morality. He pointed out that even evolution, which starts with "lower" things and develops "higher" ones, still needs a starting point with the potential for that development. For example, life can't come from truly inanimate matter without some potential for life being there first.

It's worth noting that Schiller's arguments against a purely naturalistic view of evolution have been mentioned by supporters of intelligent design in more recent times.

Schiller's Humanist Solution

Schiller proposed his "humanism" as a better way. This method recognized both the physical world we interact with and the "higher" world of purposes and ideas. He wanted philosophy to help science, not be separate from it.

For example, to explain how "higher" things like consciousness could evolve, Schiller suggested the idea of a "divine being" or a "First Cause." This being would give purpose to the world, allowing things to evolve into higher forms. This idea is called teleology, which means the study of purpose or design.

Schiller's teleology was different from older ideas. He said it wasn't about everything existing just for humans. Instead, it was about a universal purpose for the whole world. He believed this purpose was for all living beings to eventually unite in a "perfect society."

Schiller saw his philosophy as very scientific compared to the abstract ideas of his time. He used different names for his philosophy throughout his career, including "Concrete Metaphysics," "Anthropomorphism," "Pragmatism," and especially "Humanism."

The Will to Believe and Its Importance

Schiller's "will to believe" idea is a key part of his philosophy. He argued that when faced with difficult questions where other philosophies lead to doubt or sadness, we should choose to believe in solutions that give our lives meaning and purpose, even if the evidence isn't perfect. He said that if his "humanism" was the only way to see humans as having a role in the universe, then we should accept it, even if it's just a "bare possibility."

William James's essay "The Will to Believe" (1897) made Schiller expand this idea. In "Axioms as Postulates" (1903), Schiller argued that many of our basic beliefs, like the idea of causality (cause and effect) or the uniformity of nature (nature behaves consistently), are actually "postulates." This means we don't prove them first; we assume them because we need them to understand and act in the world. They are justified by how well they work in practice.

Schiller believed that these "higher" abstract ideas are tools we create to deal with the "lower" world of physical things. Their truth depends on how useful they are. He said that we don't create abstract ideas to find unchanging truths. Instead, we create them as tools to help us live in our changing, concrete world. The "truth" of these ideas comes from their practical use in helping us make predictions and shape our actions.

Schiller's View on Meaning and Truth

Schiller believed that statements only have meaning and truth when they are used in a real situation by a real person for a specific purpose. He thought that looking at statements in an abstract way, without their context, made them meaningless.

He explained that when someone says something, they are usually trying to solve a problem or achieve a goal. The meaning of the statement is how it helps achieve that purpose. The truth of the statement is whether it actually helps accomplish that purpose.

For example, if you say "diamonds are hard," the meaning and truth depend on why you are saying it.

- If you're trying to cut glass, the statement is meaningful and true if the diamond works.

- If you're just randomly saying words, it has no meaning because there's no purpose.

Schiller's view was more extreme than William James's. James thought that statements had meaning if they led to different experiences. But Schiller added that those experiences also had to matter to someone's specific goals.

He argued that a statement like "the 100th decimal of Pi is 9" doesn't have a definite truth until someone actually calculates it and has a reason to care about the answer. Until then, it's just a possibility. This shows how strongly Schiller connected truth and meaning to human purpose and action.

Selected Works

- Riddles of the Sphinx (1891)

- "Axioms as Postulates" (in Personal Idealism, 1902)

- Humanism (1903)

- Studies in Humanism (1907)

- Plato or Protagoras? (1908)

- Formal Logic (1912)

- Logic for Use (1929)

- Our Human Truths (published after his death, 1939)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Ferdinand Canning Scott Schiller para niños

In Spanish: Ferdinand Canning Scott Schiller para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |