Formation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland facts for kids

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is a country that has grown over many centuries. It's made up of different lands that joined together, sometimes through royal marriages, sometimes through laws, and sometimes through conflicts. Historians say there have been many different states in Great Britain over the last 2,000 years.

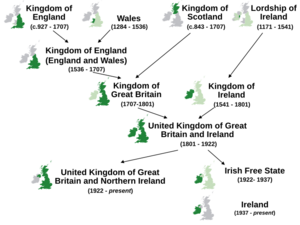

By the early 1500s, there were only two main states in Great Britain: the Kingdom of England (which included Wales and controlled Ireland) and the Kingdom of Scotland. Wales had been under English control since 1284. In 1603, the crowns of England and Scotland were united when James VI of Scotland also became James I of England. This was a "personal union" because the countries still had their own parliaments. A full "political union" happened in 1707, creating the Kingdom of Great Britain.

Later, in 1801, the Kingdom of Great Britain joined with the Kingdom of Ireland to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Ireland had slowly come under English control between 1541 and 1691. In 1922, most of Ireland became independent as the Irish Free State. Six counties in the north of Ireland stayed with the UK. Because of this, the country's name changed in 1927 to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, which is its name today.

In recent times, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland have gained their own parliaments or assemblies. This is called "devolution," meaning some powers have been moved from the main UK Parliament in London to these local bodies.

How the UK Was Formed

England Takes Over Wales

Wales was once made up of many small areas. Over time, Welsh leaders like Owain Gwynedd and Llywelyn the Great tried to unite them. Llywelyn the Great even became the first Prince of Wales.

However, the English kings wanted more control. In 1282, Edward I of England finally conquered Wales. He took over lands and created new counties. In 1284, the Statute of Rhuddlan officially put Wales under English rule, though Welsh laws were still used for a while. Edward's son, born in Wales, was made Prince of Wales. This tradition continues today, with the heir to the British throne holding the title. Edward also built many strong castles to keep control.

For a long time, much of Wales was ruled by powerful "Marcher lords" who were quite independent. But slowly, the English Crown gained control of these areas too. By 1535, Wales was fully joined with England. The Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542 made English law apply to Wales and made English the only official language. This meant Wales was now part of the Kingdom of England and had representatives in the English Parliament.

England Takes Over Ireland

In the 12th century, Ireland was divided among different powerful families. In 1155, the Pope gave the Norman King Henry II of England permission to invade Ireland to improve church practices. When an Irish king, Diarmait Mac Murchada, was exiled, he asked Henry II for help. Norman knights arrived in 1169 and helped Diarmait get his kingdom back.

Henry II worried that these Norman knights would create their own powerful state in Ireland. So, in 1171, he landed with a large army and claimed control over Ireland himself. He later gave the title "Lord of Ireland" to his son, John of England. When John became King of England, Ireland came directly under the English Crown.

Over time, English control in Ireland shrank to a small area around Dublin called the "Pale." Outside this area, many Norman lords adopted Irish language and customs.

In 1532, Henry VIII broke away from the Pope and the Catholic Church. While England, Wales, and Scotland became Protestant, most Irish people remained Catholic. This caused big problems for centuries, as England tried to conquer and settle Ireland with Protestants to prevent it from being a base for Catholic enemies.

From 1536, Henry VIII decided to fully conquer Ireland. In 1541, he declared himself "King of Ireland." The conquest was finished under Elizabeth I and James I, but it was very brutal and made the Irish resent English rule. English and Scottish Protestants were sent to settle in Ireland, especially in Ulster. These "Plantations" created a new ruling class of British Protestants. Laws were also passed that discriminated against Catholics.

Personal Union: The Union of Crowns

In 1503, James IV of Scotland married Margaret Tudor, the daughter of Henry VII of England. Almost 100 years later, in 1603, Elizabeth I of England died without children. The closest heir was James VI of Scotland, who was Margaret Tudor's great-grandson. So, James VI of Scotland became James I of England.

This was called the "Union of the Crowns." England and Scotland now shared the same king, but they were still separate countries with their own parliaments and laws. James I wanted to fully unite them into one country called "Great Britain," but neither the English nor the Scottish Parliament were keen on the idea. They feared losing their independence. So, the two kingdoms remained separate for another hundred years.

During this time, James I started a new Plantation in Ulster, Ireland, sending many Scottish and English Protestants to settle there. These settlers, surrounded by Irish Catholics, began to see themselves as "British" to show they were different from their Irish neighbours.

Ruling England, Scotland, and Ireland was hard for James I and his son, Charles I. They tried to make everyone follow the same religion. England had the Church of England, which was Protestant. Most of Ireland was Catholic. Scotland had the Church of Scotland, which was Presbyterian, though some areas were Catholic. Charles I tried to force Anglican practices on Scotland, which led to wars.

Charles I also had big arguments with the English Parliament. He believed in the "Divine Right of Kings," meaning he thought his power came directly from God. Parliament disagreed. When Charles I needed money to fight the Scots, Parliament refused unless he fixed their problems.

Meanwhile, in Ireland, Charles I's representative, Thomas Wentworth, angered Irish Catholics by taking their lands and denying them rights. He even suggested raising an Irish Catholic army to put down the Scottish rebellion. This worried both the Scottish and English Parliaments, who feared this army would be used against them.

In 1641, Irish Catholics rebelled. Rumours spread that the King supported the killings of Protestants. This led the English Parliament to raise its own army, starting the English Civil War in 1642. The Scottish Presbyterians joined Parliament's side. Charles I was defeated and executed in 1649.

After the war, Oliver Cromwell and his army conquered Ireland and then Scotland. For a short time, the three kingdoms were united as the "English Commonwealth," which was like a republic but really a military rule. This period didn't last long, and in 1660, Charles II was restored as King of England, Scotland, and Ireland. The parliaments of Scotland and Ireland were brought back.

Later, Charles II's Catholic brother, James II, became king. When James had a son, the English Parliament decided to remove him in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. They replaced him with his Protestant daughter, Mary II, and her husband, William III.

Forming the Union

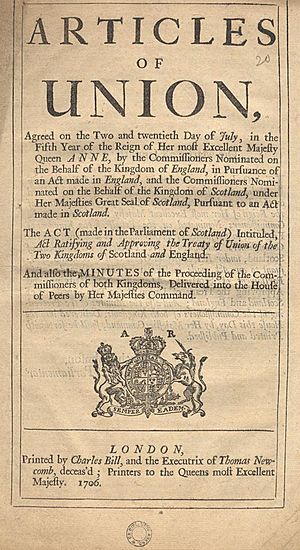

Acts of Union 1707

Queen Anne, who became queen in 1702, wanted a deeper political union between England and Scotland. In 1706, officials from both countries began talks. They agreed on a Treaty of Union.

In Scotland, there was a lot of debate and even protests against the idea of a union. Many Scots didn't want to lose their independence. However, Scotland had recently faced a huge financial disaster with the "Darien Scheme," which left its Parliament almost bankrupt. Many believed that if they didn't agree to the union, it would be forced upon them anyway, but with worse terms.

In 1707, the Acts of Union 1707 were passed. These laws officially abolished the separate Kingdoms of England and Scotland and their parliaments. They created a single Kingdom of Great Britain with one Parliament of Great Britain in Westminster. Queen Anne became the first ruler of this united kingdom.

Scotland gained free trade with England and its overseas colonies, which was a big economic benefit. For England, the union meant that Scotland could no longer be an ally for countries hostile to England, and it secured a Protestant ruler for the new British throne.

However, not everything merged. Scotland kept its own legal system, banking system, Presbyterian Church, and education system, which are still separate from England's today.

Acts of Union 1800

After the Irish Rebellion of 1641, Irish Catholics were not allowed to vote or be part of the Parliament of Ireland. The ruling class in Ireland was mostly English Protestants. By the late 1700s, the Irish Parliament had gained more independence from Britain.

However, most of Ireland's population was Catholic, and they faced harsh "Penal Laws" that limited their rights. In 1798, a rebellion broke out in Ireland, aiming to create an independent Irish republic. British forces put down this rebellion.

To prevent future rebellions and ensure British control, the British government decided to fully unite Great Britain and Ireland. The Acts of Union 1800 were passed by both the British and Irish Parliaments. It's said that many Irish politicians were bribed with titles and honours to vote for the union.

This union created "The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland" in 1801. Ireland sent its own representatives to the single Parliament of the United Kingdom in Westminster. Part of the deal was supposed to be "Catholic Emancipation," allowing Catholics to have full rights, but King George III blocked this, which made many Irish Catholics feel betrayed.

Timeline of UK Merging

| Date | Event | Areas Included | New Name | Notes | Not Included |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1284 | - | - | - | - | Separate countries: England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales |

| 1284 | Statute of Rhuddlan | England & Wales | England | Principality of Wales joined the Crown of England | Kingdom of Scotland / Lordship of Ireland |

| 1536 | Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542 | England & Wales | Kingdom of England | Wales fully became part of the Kingdom of England | Kingdom of Scotland / Lordship of Ireland (soon to be Kingdom of Ireland) |

| 1603 | Union of the Crowns | England, Scotland & Wales (under one king) | Great Britain | James VI and I became king of both England and Scotland, creating a personal union | Kingdom of Ireland |

| 1707 | Acts of Union 1707 | England, Scotland & Wales (parliaments merged) | Kingdom of Great Britain | The personal union between Scotland and England became a political union | Kingdom of Ireland |

| 1801 | Acts of Union 1800 | England, Ireland, Scotland & Wales | United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland | The Irish Parliament agreed to a political union with Great Britain | - |

| 1921 | Anglo-Irish Treaty | England, Northern Ireland, Scotland & Wales | United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland | Most of Ireland became the Irish Free State | Irish Free State (later Republic of Ireland) |

Changes to the United Kingdom

Ireland Becomes Independent

The 19th century was a difficult time for Ireland, especially during the Irish Potato Famine in the 1840s, when many people died or left the country.

Over time, Irish Nationalism grew, especially among Catholics. Many Irish politicians wanted "Home Rule," meaning Ireland would have its own parliament but still be part of the UK. When this didn't happen, an armed rebellion, the Easter Rising, took place in 1916.

In 1918, the Sinn Féin party, which wanted full independence, won most Irish elections. They set up their own Irish Parliament and declared independence, leading to the Irish War of Independence. In 1921, a treaty was signed. Most of Ireland became the Irish Free State, a self-governing country like Canada. However, Northern Ireland, which had a majority Protestant population, chose to remain part of the United Kingdom.

The "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland" officially changed its name in 1927 to the "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland." The Irish Free State later became the Republic of Ireland in 1949, completely independent from the UK.

Even though they are separate countries, Ireland and the UK still have strong ties. For example, Irish citizens can vote in all UK elections, and British citizens have similar rights in Ireland.

Devolution: Local Power

In the late 20th century, the UK government decided to give some powers back to Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. This is called "devolution." It means these parts of the UK now have their own parliaments or assemblies that can make laws on certain matters.

Northern Ireland

The Northern Ireland Assembly was created in 1998. It has the power to make laws on many local issues, like health and education. Some powers are still kept by the UK Parliament in Westminster.

Scotland

A new Scottish Parliament was set up in 1999 after people in Scotland voted for it. It can make laws on all matters that are not specifically kept by the UK Parliament. The UK Parliament can still change the powers of the Scottish Parliament.

Wales

The Senedd (or Welsh Parliament) was created in 1998. At first, it had limited law-making powers, but these grew over time. After a vote in 2011, it gained more power to make its own laws in 20 areas without needing to ask the UK Parliament. In 2020, it officially changed its name to Senedd Cymru or the Welsh Parliament.

What About the Future?

Scottish Independence

In 2014, Scotland held a vote on whether to leave the UK. About 55% of voters chose to stay. However, after the UK voted to leave the European Union in 2016 (while Scotland voted to stay), there has been talk of another vote on Scottish independence. Some recent polls show more support for independence.

Welsh Independence

Historically, support for Welsh independence has been low. However, since 2020, support has increased. Some polls now show that nearly 40% of people in Wales are in favour of independence.

Irish Reunification

Northern Ireland remains part of the UK. In 1973, there was a vote in Northern Ireland on whether to join the Republic of Ireland, but most people voted to stay in the UK. The Good Friday Agreement in 1998, a peace deal for Northern Ireland, includes a rule that another vote on Irish reunification must be held if public opinion clearly changes in favour of a united Ireland.

Images for kids

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |