Pancho Villa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pancho Villa

|

|

|---|---|

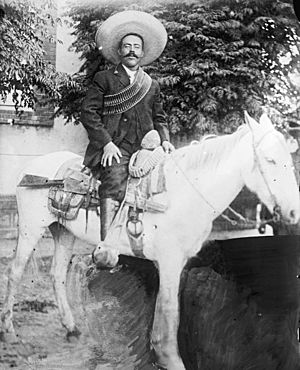

Pancho Villa on horseback c. 1908–1919

|

|

| Governor of Chihuahua | |

| In office 1913–1914 |

|

| Preceded by | Salvador R. Mercado |

| Succeeded by | Manuel Chao |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

José Doroteo Arango Arámbula

5 June 1878 La Coyotada, San Juan del Río, Durango, Mexico |

| Died | 20 July 1923 (aged 45) Parral, Chihuahua, Mexico |

| Resting place | Monument to the Revolution, Mexico City |

| Spouse |

María Luz Corral

(m. 1911) |

| Signature | |

| Nicknames | Pancho Villa El Centauro del Norte (The Centaur of the North), The Mexican Napoleon, The Lion of the North The Mexican Robin Hood |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Mexico (antireeleccionista revolutionary forces) |

| Rank | General |

| Commands | División del Norte |

| Battles/wars |

Mexican Revolution

|

Francisco "Pancho" Villa (born José Doroteo Arango Arámbula, 5 June 1878 – 20 July 1923) was a famous general in the Mexican Revolution. He was a key leader who helped remove President Porfirio Díaz from power in 1911. Later, he joined forces with others to fight against General Victoriano Huerta, who had taken over the government.

After Huerta was defeated, Villa and another revolutionary leader, Emiliano Zapata, became allies. They both wanted big changes, especially giving land to poor farmers. Villa was very popular and powerful for a time. The United States even thought about recognizing him as Mexico's leader.

However, Villa later had a big disagreement with Venustiano Carranza, another revolutionary leader. Villa's army was defeated in several battles by Carranza's general, Álvaro Obregón. After these losses, the U.S. government supported Carranza. Angry about this, Villa led a raid into Columbus, New Mexico in 1916. This caused the U.S. to send soldiers into Mexico to try and capture him, but they failed.

In 1920, Villa made a deal with the new Mexican president, Adolfo de la Huerta. He agreed to stop fighting and was given a large ranch. Pancho Villa was killed in 1923. Even though his group didn't win the Revolution, he is remembered as one of its most exciting and important figures. He was famous during his life and after his death, appearing in movies and songs. Today, his remains are buried in a special monument in Mexico City.

Contents

- Early Life and New Beginnings

- Joining the Revolution: Fighting Díaz

- Villa During Madero's Presidency (1911–1913)

- Fighting Huerta (1913–1914)

- Breaking with Carranza (1914)

- Alliance with Zapata Against Carranza (1914–1915)

- From National Leader to Guerrilla (1915–1920)

- Final Years: From Guerrilla to Ranch Owner (1920–1923)

- Personal Life

- Death

- In Historical Memory

- Legacy

- Villa's Battles and Military Actions

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and New Beginnings

Pancho Villa told different stories about his early life. Most sources say he was born José Doroteo Arango Arámbula on June 5, 1878. He grew up on a large farm called Rancho de la Coyotada in Durango, Mexico. His family were sharecroppers, meaning they farmed land owned by someone else.

After his father died, young Doroteo helped his mother. He worked many jobs, like a farmhand, a butcher, and a bricklayer. He also worked for a U.S. railway company.

When he was 16, he left home and became a thief, roaming the hills. He was known as "Arango" in a bandit group. In 1898, he was arrested for stealing guns and mules.

In 1902, the police force of President Porfirio Díaz arrested him again. Because he knew powerful people, he avoided a harsh punishment. Instead, he was forced to join the Mexican army. But he soon ran away and went to the state of Chihuahua.

In 1903, after another incident, he changed his name to Francisco "Pancho" Villa. He took this name from his grandfather. His friends also called him La Cucaracha (The Cockroach).

Before 1910, Villa sometimes worked regular jobs and sometimes continued his bandit activities. His life changed when he met Abraham González. González was a supporter of Francisco Madero, who wanted to become president and end Díaz's rule. González convinced Villa that he could use his skills to fight for the common people against the wealthy landowners.

When the Mexican Revolution began in 1910, Pancho Villa was 32 years old.

Joining the Revolution: Fighting Díaz

For Pancho Villa and others like him, the start of the Mexican Revolution in 1910 was a chance for a new purpose. Villa joined the armed fight that Francisco Madero called for to remove President Porfirio Díaz. In Chihuahua, Abraham González asked Villa to join the movement.

Villa quickly showed his military talent. He captured a large farm, then a train full of soldiers, and the town of San Andrés. He won battles against the army in places like Naica and Camargo.

In March 1911, Villa met Madero in person. Madero made Villa a colonel in the revolutionary forces.

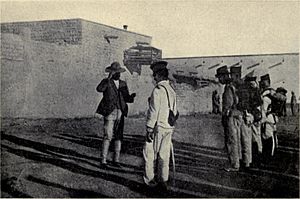

Much of the fighting happened in northern Mexico, near the U.S. border. Madero wanted to avoid U.S. involvement, so he ordered his officers not to attack the important border city of Ciudad Juárez. But Villa and Pascual Orozco ignored the order. They attacked and captured the city in two days, winning the first Battle of Ciudad Juárez in 1911.

After many defeats, President Díaz resigned on May 25, 1911, and went into exile. However, Madero signed a treaty that kept much of the old power structure, including the army that had just been defeated.

Villa During Madero's Presidency (1911–1913)

After Díaz left, the rebel forces, including Villa, were told to go back to their normal lives. Villa and Orozco wanted the land taken during the revolution to be given to the soldiers. Madero said the government would buy the land later and then give it out. Villa was unhappy with this. He believed Madero was making a mistake by not giving land to the people who fought for him.

Madero became president in November 1911. He didn't keep his revolutionary supporters close and instead relied on the old government system. Villa strongly disagreed with Madero's choice to make Venustiano Carranza his Minister of War.

In March 1912, Orozco started a rebellion because Madero hadn't made land reforms and hadn't rewarded him enough. Villa returned to military service to fight Orozco's rebellion. Villa helped Madero win important battles.

Villa joined forces with the army led by General Victoriano Huerta. Huerta at first welcomed Villa and made him an honorary general. But Villa was not easily controlled. Huerta then tried to get rid of Villa by accusing him of stealing a horse and calling him a bandit. Villa reacted strongly, and Huerta ordered Villa's execution.

As Villa was about to be executed, he appealed to Madero's brothers. They intervened, and President Madero ordered Huerta to spare Villa's life but imprison him.

Villa was held in two different prisons in Mexico City. While in prison, he learned more about reading, writing, and history. He also learned about Emiliano Zapata's plan for land reform. Villa escaped from prison on Christmas Day 1912. He went to the United States.

In February 1913, Madero was killed in a military takeover, and Huerta became president. Villa was in the U.S. when this happened. With only a few men and supplies, he returned to Mexico in April 1913 to fight Huerta, who had tried to execute him.

Fighting Huerta (1913–1914)

Huerta quickly took full control. He had Abraham González, Villa's friend and mentor, killed in March 1913. Villa later found González's remains and gave him a proper funeral.

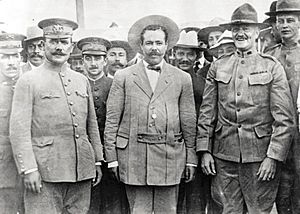

The governor of Coahuila, Venustiano Carranza, also refused to accept Huerta's rule. Carranza created a plan to remove Huerta. Villa joined Carranza to overthrow Huerta, even though he often made fun of Carranza. This group was called the Ejército Constitucionalista de México (Constitutionalist Army of Mexico). They wanted to show that Huerta had taken power illegally.

The years 1913–1914 were when Villa became very famous and had great military success. During this time, Villa got money by asking wealthy landowners for loans and by robbing trains. In one famous event, he robbed a train and held a Wells Fargo employee hostage until the company helped him sell silver bars for cash.

Villa won many quick and tough battles in places like Ciudad Juárez, Tierra Blanca, and Ojinaga.

An American journalist named John Reed spent four months with Villa's army. He wrote exciting stories about Villa, his soldiers, and the women who fought with them. These stories were published in a book called Insurgent Mexico in 1914. Reed's writings helped create Villa's image as a hero in America. He wrote about Villa taking cattle, corn, and gold and giving them to the poor. U.S. President Woodrow Wilson even called Villa "a sort of Robin Hood."

Villa as Governor of Chihuahua

Villa was a brilliant military leader, and this brought him political support. In 1913, local military leaders chose him as the temporary governor of Chihuahua. Carranza had wanted someone else, but Villa was more popular.

As governor, Villa brought in more experienced generals to his team. He also found ways to raise money for the war against Huerta's army. He printed his own money and made sure it was accepted everywhere. He made wealthy people give loans to the revolution. He also took gold from banks and even held a rich family member hostage until they revealed where their hidden gold was.

Villa also took land from large farm owners and used the money from these farms to fund the military and help families who had lost members in the revolution. He promised that after the revolution, the land would be given back to veterans, former owners, and the state. These actions, along with gifts and lower costs for the poor, made Villa very popular in Chihuahua. After four weeks, Villa stepped down as governor at Carranza's suggestion.

With plenty of money, Villa made his army bigger and more modern. He bought animals, weapons, and even mobile hospitals. He also rebuilt the railroad south of Chihuahua City. He recruited many fighters and created the División del Norte (Division of the North), which became the strongest and most feared army in Mexico. This army used the rebuilt railroad to move troops and artillery south, where they defeated Huerta's forces in many battles, including the important city of Zacatecas.

Winning at Zacatecas (1914)

After Villa captured the important city of Torreón, Carranza ordered him to attack Saltillo instead of moving directly towards Mexico City. Carranza wanted his own forces to take the capital first. This order caused problems for Villa, as his soldiers were paid, and every delay cost a lot of money.

Even though he was annoyed, Villa followed Carranza's order and captured Saltillo. He then tried to make peace with Carranza, but Carranza refused. Carranza then ordered 5,000 of Villa's soldiers to help capture Zacatecas, a heavily defended city. Villa believed this would fail unless he led the attack himself. Carranza refused to let Villa lead, as he didn't want Villa to get the credit for winning Zacatecas.

Villa resigned from his position, but his officers convinced him to stay and attack Zacatecas. Defying Carranza, the División del Norte attacked Zacatecas. They fought up steep hills and defeated 12,000 soldiers in the Toma de Zacatecas (Taking of Zacatecas). This was the bloodiest battle of the Revolution, with thousands of soldiers killed or wounded.

Villa's victory at Zacatecas in June 1914 crushed Huerta's government. Huerta left the country on July 14, 1914, and the old army fell apart. As Villa moved towards the capital, his progress slowed because of a lack of coal for his trains. The U.S. government also stopped sending supplies to Mexico. This was likely because the U.S. didn't want any one group to become too powerful.

Breaking with Carranza (1914)

The disagreements between Villa and Carranza became clear after Huerta was defeated. They had made a temporary agreement to stay united, but their goals were different. Carranza was a wealthy landowner, and he saw Villa as little more than a bandit, despite Villa's military successes. Villa saw Carranza as a weak civilian leader, while Villa's army was the largest and most successful.

In August and September 1914, General Obregón tried to get Villa and Carranza to agree. They agreed that Carranza should be the temporary president and that land reform should happen quickly. They also agreed that the military should be separate from politics. However, Carranza didn't want to be temporary president because it would stop him from running in the next election.

During a second meeting, Villa became very angry with Obregón and almost had him executed. But Obregón calmed him down, and Villa let him leave. Even though Obregón had his own issues with Carranza, his meetings with Villa convinced him to stay loyal to Carranza. Obregón saw Villa as someone who wouldn't keep his promises. In September 1914, Villa officially broke with Carranza.

Alliance with Zapata Against Carranza (1914–1915)

After Huerta was removed, the different revolutionary groups began to fight among themselves for power. The leaders held a meeting called the Convention of Aguascalientes to try and decide who would lead. They chose Eulalio Gutiérrez as the temporary president.

Emiliano Zapata, a general from southern Mexico, also sent representatives to the meeting. Zapata and Villa shared similar views about Carranza and formed an alliance. They feared Carranza wanted to be a dictator, not a democratic leader. So, Villa and Zapata broke away from Carranza. This led to a civil war among the former allies.

Carranza and Álvaro Obregón moved to Veracruz, leaving Villa and Zapata to take over Mexico City. Even though Villa had a stronger army, Obregón was a better strategist. Obregón helped Carranza use the Mexican newspapers to make Villa look like a dangerous bandit. This hurt Villa's standing with the U.S.

Carranza controlled two important states with Mexico's largest ports, Veracruz and Tamaulipas. This meant he could collect more money than Villa. In 1915, Villa had to leave Mexico City after some problems with his troops, which allowed Carranza to return.

To fight Villa, Carranza sent his best general, Obregón, north. Obregón defeated Villa in a series of battles. At the Battle of Celaya in April 1915, Villa's army suffered a huge loss, with thousands killed or captured. Obregón defeated Villa again at the Battle of Trinidad.

In October 1915, Villa went into Sonora, where Obregón and Carranza's armies were strong. He hoped to defeat Carranza there, but Carranza had strengthened his forces, and Villa was badly defeated again. Many of Villa's soldiers left his army after these losses, and 1,500 of them accepted an offer of forgiveness from Carranza. Villa's famous Division del Norte was no longer a major fighting force.

Only about 200 men remained loyal to Villa, and he was forced to retreat into the mountains of Chihuahua. His position became even weaker when the United States stopped selling him weapons. By the end of 1915, Villa was on the run, and the U.S. government officially recognized Carranza as Mexico's leader.

From National Leader to Guerrilla (1915–1920)

After his defeats by Obregón, Villa's army became much smaller. His enemies thought he was finished. Villa decided to split his remaining forces into small, independent groups and fight as guerrillas from the hills. This was a strategy he knew well from his bandit days. He had loyal followers from Chihuahua and Durango.

During this time, towns were often controlled by the government, while the countryside was controlled by guerrillas. Civilians often suffered during these conflicts.

The United States had supported Villa, but after his defeats, they stopped supplying his army. They even allowed Carranza's troops to use U.S. railroads. President Woodrow Wilson believed supporting Carranza was the best way to bring stability to Mexico. Villa was very angry when Obregón used U.S.-powered searchlights to help stop a night attack by Villa's men on the border town of Agua Prieta in November 1915.

In January 1916, some of Villa's men attacked a train near Santa Isabel, Chihuahua. They killed several U.S. citizens who worked for an American company. Villa said he ordered the attack but denied he meant to kill U.S. citizens.

Villa then gathered more men, bringing his force to about 500 guerrillas. He began planning an attack on U.S. soil.

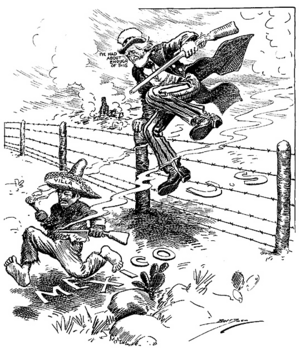

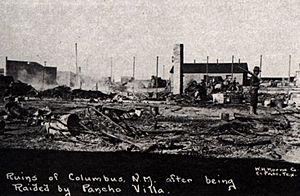

Attack on New Mexico

On March 9, 1916, General Villa ordered about 100 of his men to cross the border and attack Columbus, New Mexico. Some believed the raid was because the U.S. government recognized Carranza and because Villa's army had lost lives due to faulty ammunition bought from the U.S. However, from a military view, Villa likely did it to get more military equipment and supplies to continue fighting Carranza.

Villa's men attacked a U.S. Army group, burned parts of the town, and took horses, mules, and other military supplies. Eighteen Americans and about 80 of Villa's men were killed.

U.S. Expedition to Capture Villa

In response to the Columbus raid, President Wilson sent 5,000 U.S. Army soldiers into Mexico. General John Pershing led this group, known as the Punitive Expedition. They used aircraft and trucks for the first time in U.S. Army history to chase Villa. But Villa managed to avoid them until February 1917.

During the expedition, some of Villa's top commanders and about 190 of his men were killed. The Mexican government and people were against U.S. troops being in Mexico. There were many protests against the expedition. Carranza's forces also captured and executed one of Villa's top generals, Pablo López, in June 1916.

Final Years: From Guerrilla to Ranch Owner (1920–1923)

After his military defeats and the U.S. military intervention, Villa stopped being a national leader and became a guerrilla leader in Chihuahua. While Villa was still active, Carranza focused on fighting Zapata in the south. Villa's last big military action was a raid against Ciudad Juárez in 1919. After this raid, Villa suffered another blow when Felipe Angeles, one of his trusted generals, left him. Angeles was later captured and executed by Carranza's forces.

Villa continued fighting, but his forces were small. His new second-in-command, Martín López, was killed during a siege in Durango. At this point, Villa was ready to stop fighting if he received a good offer.

On May 21, 1920, a big change happened for Villa: Carranza was killed by supporters of Álvaro Obregón. With his main enemy gone, Villa was ready to make peace and retire. On July 22, 1920, Villa sent a telegram to the new Mexican interim President Adolfo de la Huerta, saying he recognized his presidency and asked for forgiveness. Six days later, De la Huerta met with Villa and they agreed on a peace settlement.

In exchange for stopping his fighting, Villa was given a large ranch of 25,000 acres in Canutillo, Chihuahua. He also owned another estate in Chihuahua City with his wife, María Luz Corral de Villa. The remaining 200 loyal guerrillas and veterans of Villa's army were allowed to live with him on his new ranch. The Mexican government also gave them a pension of 500,000 gold pesos. The 50 guerrillas who were still in Villa's small cavalry were allowed to be his personal bodyguards.

Personal Life

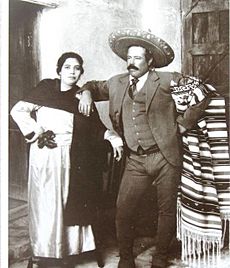

Pancho Villa had several relationships and marriages during his life. On May 29, 1911, he married María Luz Corral, who was known as one of his most important wives. They met when she lived with her mother in San Andrés, where Villa had his headquarters. They were married by a priest in a big ceremony. A photo from 1914 shows Luz Corral with Villa. After Villa's death, courts twice confirmed that her marriage to Villa was valid. They had one daughter who died young.

Villa also had long-term relationships with other women. Austreberta Rentería was considered his "official wife" at his Canutillo ranch, and they had two sons, Francisco and Hipólito. He also had relationships with Soledad Seañez and Manuela Casas (with whom he had a son), and Juana Torres, whom he married in 1913 and had a daughter with.

When Villa was killed in 1923, Luz Corral was not at Canutillo. However, Mexican courts recognized her as Villa's legal wife and heir to his property. President Obregón supported Luz Corral's claim, perhaps because she had helped save his life when Villa threatened him in 1914.

Years later, Rentería and Seañez were given small government pensions. Luz Corral inherited Villa's estate and helped keep his memory alive. All three women often visited Villa's grave in Parral. When Villa's remains were moved to the Monument to the Revolution in Mexico City in 1976, Luz Corral chose not to attend the large ceremony. She passed away in 1981 at 89 years old.

Villa's last living son, Ernesto Nava, died in California in 2009 at the age of 94.

Death

On July 20, 1923, Pancho Villa was killed in an ambush while visiting Parral. It is believed that political enemies, including Plutarco Elías Calles and President Alvaro Obregón, ordered his death. Villa often traveled from his ranch to Parral for banking and felt safe there.

On that day, he went into town with only a few bodyguards and ranch employees, instead of his usual large group. He was picking up gold from the bank to pay his ranch workers. As he drove back through the city in his black 1919 Dodge car, a person shouted "Viva Villa!" This was a signal to seven gunmen who appeared in the road. They fired more than 40 shots into the car.

Claro Huertado, Rafael Madreno, Danie Tamayo, and Colonel Miguel Trillo were all killed. One of Villa's bodyguards, Ramon Contreras, was badly wounded but managed to kill at least one attacker before escaping. Contreras was the only survivor. Historians believe Villa died instantly.

Telephone service to Villa's ranch was cut off, likely to prevent any uprising by his supporters.

The next day, Villa's funeral was held in Parral. Thousands of his supporters followed his coffin to his burial site. The six surviving assassins were captured, but only two spent a few months in jail. The others were even allowed to join the military.

Villa was likely killed because he was talking about returning to politics for the 1924 elections. Obregón could not run for president again and wanted his ally, Plutarco Elías Calles, to win. Villa's return to politics would have made things difficult for them.

It has never been officially proven who was responsible for the assassination. However, most historians believe it was a planned attack likely started by Plutarco Elías Calles and General Joaquín Amaro, with Obregón's approval. Jesús Salas Barraza, a local politician, claimed he was solely responsible. He said he was paid 50,000 pesos by Villa's enemies to kill him. Barraza admitted that he and his group watched Villa's daily drives and used the pumpkinseed vendor to signal when Villa was in the car.

Obregón had Barraza arrested. He was first sentenced to 20 years in prison, but his sentence was reduced to three months. Salas Barraza later became a colonel in the Mexican Army. Before he died, he reportedly said, "I'm not a murderer. I rid humanity of a monster."

Others involved in the plot included Félix Lara, a military commander who was paid to remove soldiers and police from Parral on the day of the killing, and Melitón Lozoya, who planned the details and found the gunmen.

Aftermath of His Death

Villa was buried the day after his death in the city cemetery of Parral, not in Chihuahua City where he had built a mausoleum. His remains were later moved to the Monument to the Revolution in Mexico City in 1976. The Francisco Villa Museum is a museum dedicated to Villa at the site of his assassination in Parral.

In Historical Memory

Villa is a very famous figure in Mexico, but there are relatively few places named directly after him. In Mexico City, there is a subway station called Metro División del Norte, which indirectly honors Villa through the name of his revolutionary army.

-

Monument to Pancho Villa in Bufa Zacatecas mountain range

Legacy

According to his biographer, Friedrich Katz, Pancho Villa was seen as someone who destroyed the old ways. But this destruction had positive sides. Villa played a key role in bringing down Huerta's government and the entire old system. During his short time as governor of Chihuahua, he made important land reforms. By taking land from wealthy owners, he weakened that class. Later, in the 1930s, President Lázaro Cárdenas finished breaking up the old land system.

Villa's raid on Columbus, New Mexico, also affected relations between the Carranza government and the U.S. Banks in the U.S. stopped lending money to Carranza, making it harder for him to control rebellions. Katz believes Villa's time as governor was very effective and helped the common people economically. He called it "the first welfare state in Mexico" in some ways.

Today, Villa's remains are buried in the Monument to the Revolution in Mexico City. His name was also added to the wall of Mexican heroes in the Chamber of Deputies. Both of these official recognitions caused some debate. But because Villa's image wasn't quickly taken over by the ruling political party, his memory and legend stayed strong in the hearts of the people. People liked the idea of Villa as a daring "Robin Hood" figure.

However, not everyone praises Villa. Some historians emphasize his past as a bandit, saying the Revolution just gave him a new title, not a new way of life.

Among the main figures of the Revolution, Villa and Zapata are the most well-known to the public. They are seen as defenders of the poor. In contrast, leaders like Madero, Carranza, and Obregón are less known outside of Mexico. It took many years for Villa to be officially recognized as a hero of the Revolution. In death, his remains rest near some of his fierce opponents, like Venustiano Carranza.

Villa's Battles and Military Actions

Pancho Villa's many victories from the start of the Mexican Revolution were very important in bringing down Porfirio Díaz, helping Francisco Madero win, and removing Victoriano Huerta from power. He is still seen as a heroic figure by many Mexicans. His military actions included:

- Battle of San Andrés (1910 won)

- Battle of Santa Isabel (1910 won)

- First Battle of Ciudad Juárez, with Pascual Orozco (1911 won)

- Second Battle of Ciudad Juárez (1913 won)

- Battle of Tierra Blanca (1913 won)

- Battle of Chihuahua (1913 won)

- Battle of Ojinaga (1914 won)

- First Battle of Torreón (1914 won)

- Second Battle of Torreón (1914 won)

- Battle of San Pedro de las Colonias (1914 won)

- Battle of Paredón (1914 won)

- Battle of Lerdo (1914 won)

- Batalla de Gómez Palacio (1914 won)

- Battle of Saltillo (1914 won)

- Battle of Zacatecas (1914 won)

- Battle of Celaya (1915 lost)

- Battle of Trinidad (1915 lost)

- Battle of Agua Prieta (1915 lost)

- Battle of Columbus, N.M. (1916 won)

- Battle of Guerrero (1916 won)

- Battle of Chihuahua (1916 won)

- Third Battle of Torreón (1916 won)

- Battle of Parral (1918 won)

- Third Battle of Ciudad Juárez (1919 lost)

- Siege of Durango (1919 lost)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Pancho Villa para niños

In Spanish: Pancho Villa para niños

- Constitutionalist Army

- Mexican Revolution

- Pancho Villa Expedition

- Pancho Villa in popular culture