Francisco I. Madero facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Francisco I. Madero

|

|

|---|---|

Francisco Ignacio Madero González

|

|

| 37th President of Mexico | |

| In office 9 November 1911 – 19 February 1913 |

|

| Vice President | José María Pino Suárez |

| Preceded by | Francisco León de la Barra |

| Succeeded by | Pedro Lascuráin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 30 October 1873 Parras de la Fuente, Coahuila, Mexico |

| Died | 22 February 1913 (aged 39) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Resting place | Monument to the Revolution Mexico City, Mexico |

| Political party | Progressive Constitutionalist Party (previously the Anti-Reelectionist Party) |

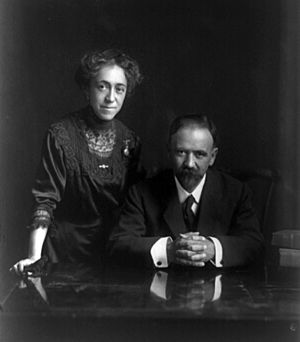

| Spouses | Sara Pérez, no children |

| Relations | Brothers: Ernesto Madero Emilio Madero Gustavo A. Madero Raúl Madero Gabriel Madero |

| Parents | Francisco Madero Hernández (father) Mercedes González Treviño (mother) |

| Residence | Coahuila |

| Education | Lycée Hoche de Versailles |

| Alma mater | HEC Paris University of California, Berkeley |

| Profession | Writer, revolutionary |

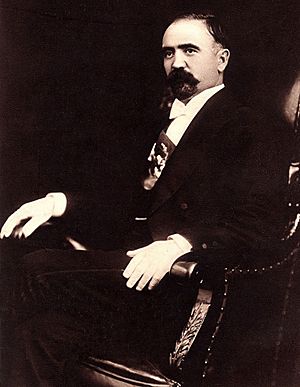

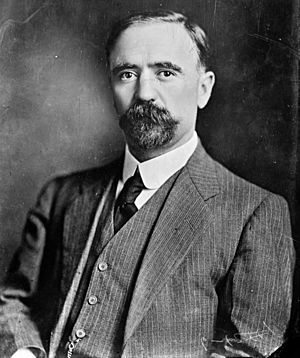

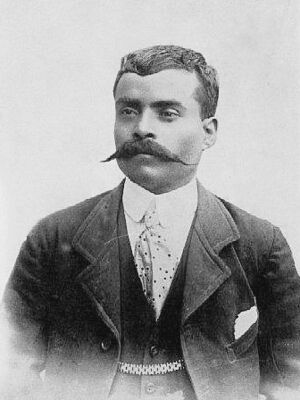

Francisco Ignacio Madero González (born October 30, 1873 – died February 22, 1913) was a Mexican businessman, writer, and revolutionary leader. He became the 37th president of Mexico in 1911. However, he was removed from power in a sudden overthrow (called a coup d'etat) in February 1913 and was then killed.

Madero came from one of Mexico's richest families. He studied business in Paris, France. He believed strongly in fairness for all people and in democracy. In 1908, he wrote a book called The Presidential Succession in 1910. This book asked Mexican voters to stop Porfirio Díaz from being re-elected. Díaz had been president for a very long time and his government had become very strict.

Madero helped pay for the opposition party, the Anti-Reelectionist Party. His campaign gained a lot of support across the country. He ran against Díaz in the 1910 election, but was arrested. Díaz then declared himself the winner for an eighth time in an unfair election. Madero escaped from jail and went to the United States. There, he wrote the Plan of San Luis Potosí, which called for a revolution to overthrow Díaz. This plan started the Mexican Revolution.

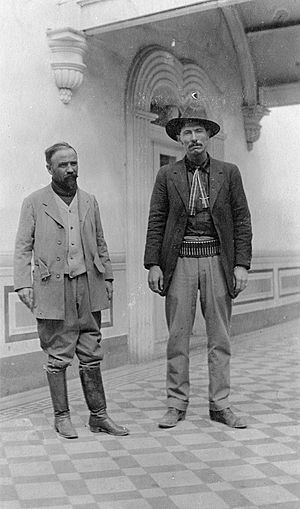

Madero's armed supporters were mostly in northern Mexico. They got weapons and money from the United States. In Chihuahua, Madero asked wealthy landowner Abraham González to join his movement. González then recruited Pancho Villa and Pascual Orozco as revolutionary leaders. Madero crossed from Texas into Mexico and led a group of revolutionaries. However, they lost the Battle of Casas Grandes to the Federal Army. After this, Madero stopped leading battles himself.

Madero was worried that the Battle of Ciudad Juárez would hurt people in the American city of El Paso. He also feared it would cause other countries to get involved. So, he told Villa and Orozco to stop fighting. But they did not listen and captured Juárez. Díaz resigned on May 25, 1911, after signing the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez. He then went to live in another country. Madero kept the Federal Army in place and sent away the revolutionary fighters who had forced Díaz to resign.

Madero was very popular with many people. But he did not become president right away. An interim (temporary) president was put in charge, and new elections were planned. Madero won the election by a huge amount and became president on November 6, 1911.

Madero's government soon faced problems from both conservative groups and more radical revolutionaries. He was slow to make big changes to land ownership. This upset many of his followers who felt it was a promise from the revolution. Workers also became unhappy with his moderate plans. Emiliano Zapata, who had supported Madero, started a rebellion against him in 1911 with the Plan of Ayala. In the north, Pascual Orozco, another former supporter, also led a rebellion. Other countries worried that Madero could not keep Mexico stable.

In February 1913, a coup d'etat (a sudden overthrow of the government) happened in Mexico City. It was led by conservative Generals Félix Díaz (Porfirio Díaz's nephew), Bernardo Reyes, and Victoriano Huerta. Huerta took over the presidency. Madero was captured and killed along with his vice-president, José María Pino Suárez. These events are now known as the Ten Tragic Days. Madero's brother, Gustavo A. Madero, was also killed.

After his death, Madero became a symbol that united different revolutionary groups against Huerta's government. In the north, Venustiano Carranza, the Governor of Coahuila, led the new Constitutionalist Army. Meanwhile, Zapata continued his rebellion against the government. After Huerta was removed in July 1914, the revolutionary groups met. But they still disagreed, and Mexico entered a new period of civil war.

Contents

Early Life and Family (1873–1903)

Family Background

Francisco Madero was born in 1873 into a very rich and large family in northeastern Mexico. His birthplace was the hacienda (a large estate) of El Rosario, in Parras de la Fuente, Coahuila. His grandfather, Evaristo Madero, had built a huge fortune from many different businesses. He was briefly the Governor of Coahuila from 1880 to 1884.

Evaristo started a business transporting goods. He made money by moving cotton from the southern U.S. states to Mexican ports during the U.S. Civil War (1861–65). He also founded a company that grew grapes for wine, cotton, and made textiles. Later, this company also got involved in mining, ranching, banking, and other industries.

The Madero family became one of the richest in Mexico by 1910. Their wealth came from many different businesses, including growing guayule rubber plants.

Francisco's father was interested in spiritism, a philosophical movement. Young Francisco was sent to Paris to study business, along with his brother Gustavo. Francisco also became very interested in spiritism. He believed he could communicate with spirits.

Francisco I. Madero was the first son of Francisco Ignacio Madero Hernández and Mercedes González Treviño. He was the first grandson of Evaristo. Francisco was the first of his father's eleven children. His wealthy family could give him many resources when he challenged Porfirio Díaz in 1910. He was a sickly child and remained small as an adult.

After becoming president in 1911, Francisco appointed his uncle Ernesto Madero Farías as his Minister of Finance. This led to some people accusing him of favoring his family. Francisco was very close to his brother Gustavo A. Madero, who was a trusted advisor when he was president. Gustavo was killed during the coup that removed Francisco from power. His other brothers, Emilio, Julio, and Raúl, also fought in the Mexican Revolution.

Francisco I. Madero and his wife, Sara Pérez, did not have children. However, the descendants of Evaristo Madero are still some of Mexico's most important families today.

Education and Beliefs

Francisco and his younger brother Gustavo A. Madero went to a Jesuit school in Saltillo. Between 1886 and 1892, Madero studied in France and the United States. He attended the Lycée Hoche in Versailles, France, and then the prestigious HEC Paris for business.

While in Paris, Madero became very interested in Spiritism. He visited the tomb of Allan Kardec, who founded Spiritism. Madero became a strong believer and thought he was a medium (someone who can communicate with spirits). After business school, Madero studied at the University of California, Berkeley. There, he learned about farming techniques and improved his English. He was also influenced by the ideas of theosophy.

Return to Mexico and Philanthropy

In 1893, Madero returned to Mexico at age 20. He took over managing one of his family's haciendas in San Pedro, Coahuila. He was well-traveled and educated, and now in good health. Francisco was a forward-thinking manager. He installed new irrigation systems, brought in American cotton and machinery, and built factories for soap and ice.

He also started a lifelong commitment to helping others. His employees were paid well and received regular medical check-ups. He built schools, hospitals, and community kitchens. He also paid to support orphans and gave out scholarships. He even learned homeopathy and offered medical treatments to his employees.

By 1899, he had built his own fortune of over 500,000 pesos. He invested in mines with his family. In January 1903, he married Sara Pérez.

Political Beginnings (1903–1909)

First Steps in Politics

On April 2, 1903, Bernardo Reyes, the governor of Nuevo León, violently stopped a political protest. This showed how strict President Porfirio Díaz's government was becoming. Madero was deeply affected by this event. Believing he was getting advice from the spirit of his dead brother Raúl, he decided to act. Raúl's spirit told him to "Aspire to do good for your fellow citizens... working for a lofty ideal."

Madero started the Benito Juárez Democratic Club and ran for local office in 1904, but he lost. He also continued his interest in Spiritism, writing articles under the pen name Arjuna.

In 1905, Madero became more involved in opposing Díaz's government. He formed political clubs and started a political newspaper called El Demócrata. He also created a satirical magazine called El Mosco ("The Fly"). Díaz thought about jailing Madero, but Reyes suggested that Madero's father should control his son instead.

Leading the Anti-Re-election Movement

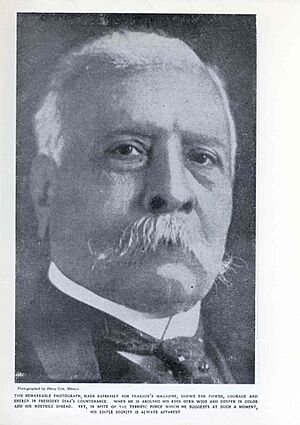

In an interview published in February 1908, President Díaz said that Mexico was ready for democracy. He claimed the 1910 presidential election would be fair.

Madero spent most of 1908 writing a book, which he believed spirits guided him to write. This book, La sucesión presidencial en 1910 (The Presidential Succession of 1910), was published in January 1909. It quickly became very popular in Mexico. The book stated that Díaz's long and absolute power had harmed Mexico. Madero pointed out that Díaz's own slogan in 1871 had been "No Re-election."

Madero admitted that Díaz had brought peace and some economic growth to Mexico. However, he argued that this came at the cost of freedom. He mentioned the harsh treatment of the Yaqui people, the repression of workers, and too much power given to the United States. Madero called for Mexico to return to the liberal 1857 Constitution. To do this, he suggested forming a Democratic Party with the slogan Sufragio efectivo, no reelección ("Effective Suffrage. No Re-election"). He believed Díaz should either run in a fair election or retire.

Madero's book was well-received and widely read. Many people started calling Madero "the Apostle of Democracy." Madero sold much of his property, often at a loss, to pay for anti-re-election activities across Mexico. He founded the Anti-Re-election Center in Mexico City in May 1909. He also supported the newspaper El Antirreeleccionista. In Puebla, Aquiles Serdán formed an Anti-Re-electionist Club to organize for the 1910 elections, especially among workers. Madero traveled throughout Mexico, giving speeches against re-election. Everywhere he went, thousands of people came to greet him.

Despite Madero's actions, Díaz decided to run for re-election. Díaz and U.S. President William Howard Taft planned a meeting in El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, for October 16, 1909. This was the first time a Mexican and a U.S. president met, and the first time a U.S. president crossed into Mexico.

The meeting was a success for Díaz. However, on the day of the meeting, a man with a hidden gun was found near Díaz and Taft. He was quickly disarmed.

Díaz's government tried to pressure the Madero family's banking businesses. They even tried to arrest Madero for "unlawful transaction in rubber." But Madero was not arrested, partly because Díaz's finance minister, José Yves Limantour, who was a friend of the Madero family, helped him. In April 1910, the Anti-Re-electionist Party chose Madero as their candidate for President of Mexico.

Madero met with Díaz on April 16, 1910. Only the two men were present. Madero realized that Díaz was an old man who was out of touch with politics. This meeting made Madero even more determined that a political compromise was not possible. He warned his supporters that Díaz might cheat in the election and said, "Force shall be met by force!"

Campaign, Arrest, and Escape (1910)

Madero campaigned across the country, promising reforms. He met with many supporters. Many poor and middle-class Mexicans supported Madero. They were unhappy that the United States controlled much of Mexico's resources.

Fearing a big change, Díaz's government arrested Madero in Monterrey on June 6, 1910. He was sent to a prison in San Luis Potosí. About 5,000 other members of the Anti-Re-electionist movement were also jailed. While Madero was in jail, an unfair election was held on June 21, 1910. It gave Díaz a huge victory.

Madero's father used his influence to get Madero permission to move around the city during the day. On October 4, 1910, Madero escaped from his guards. He found safety with supporters in a nearby village. Three days later, he was secretly taken across the U.S. border by sympathetic railway workers. He settled in San Antonio, Texas, where he planned his next steps. He wrote the Plan of San Luis Potosí in San Antonio.

The Mexican Revolution Begins

Plan of San Luis Potosí and Rebellion

In San Antonio, Texas, Madero quickly released his Plan of San Luis Potosí. This plan declared the 1910 elections invalid. It called for an armed revolution to begin at 6 p.m. on November 20, 1910, against Díaz's "illegitimate presidency/dictatorship." Madero declared himself the temporary President of Mexico. He called for people to refuse to recognize the central government. The plan also promised to return land to villages and Native American communities and to free political prisoners. Madero's ideas appealed to different groups in Mexico.

Madero's family used their money to help the revolution. Madero's brother Gustavo A. Madero hired a lawyer in Washington, D.C., to gain support in the U.S. The U.S. government "bent neutrality laws" to help the revolutionaries. A U.S. Senate hearing in 1913 found that the Maderos spent about $400,000 (about $1.5 million today) on the revolution.

El Paso, Texas, became a key place for Madero's uprising against Díaz. It is across the Rio Grande from Ciudad Juárez. Two Mexican railway lines connected there with a U.S. railway. As political tensions grew, smuggling guns and ammunition to the rebels became a big business.

Madero stayed in San Antonio, but his main contact in Chihuahua, Abraham González, recruited skilled military leaders: Pancho Villa and Pascual Orozco. Chihuahua became the center of the rebel activity. Villa and Orozco had more and more success against the Federal Army. This drew more people to Madero's cause, as it seemed to have a real chance of winning.

On November 20, 1910, Madero arrived at the border. He planned to meet 400 men led by his uncle to attack Ciudad Porfirio Díaz. However, his uncle arrived late with only ten men. Madero decided to delay the revolution. Instead, he and his brother Raúl traveled secretly to New Orleans, Louisiana.

On February 14, 1911, Madero crossed into Chihuahua state from Texas. On March 6, 1911, he led 130 men in an attack on Casas Grandes, Chihuahua. Madero was not a military leader. He initially captured the town but did not realize he needed to check for Federal Army reinforcements. There were many casualties among the rebels, including foreigners from the U.S. and Germany. Madero was slightly wounded in his right arm. He was saved by his bodyguard, General Máximo Castillo. Madero remained the leader of the movement in the north to remove Díaz.

The Madero movement successfully brought weapons from the United States. Some were shipped from New York, disguised to avoid being stopped by the U.S. government. Two businesses in El Paso sold weapons to the rebels. The U.S. government tried to stop the flow of arms, but failed.

By April, the Revolution had spread to eighteen states. This included Morelos, where Emiliano Zapata was the leader. On April 1, 1911, Porfirio Díaz claimed he had heard the people of Mexico. He replaced his cabinet and agreed to return land to those who had lost it. Madero did not believe him. Instead, he demanded that President Díaz and Vice-President Ramón Corral resign. Madero then met with other revolutionary leaders. They agreed on a plan that included paying revolutionary soldiers, freeing political prisoners, and allowing revolutionaries to name some cabinet members. Madero was moderate. He wanted to proceed carefully to avoid too much bloodshed and make a deal with Díaz if possible.

In early May, Madero wanted a ceasefire. But his fellow revolutionaries, Pascual Orozco and Pancho Villa, disagreed. They attacked Ciudad Juárez on May 8 without orders. The city surrendered after two days of fierce fighting. The revolutionaries won this battle decisively. It became clear that Díaz could no longer stay in power.

On May 21, 1911, the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez was signed. Under this treaty, Díaz and Corral agreed to resign by the end of May 1911. Díaz's Foreign Affairs Minister, Francisco León de la Barra, became interim president. His only job was to call for new general elections. Madero did not want to take power by force. He wanted to win through a democratic election.

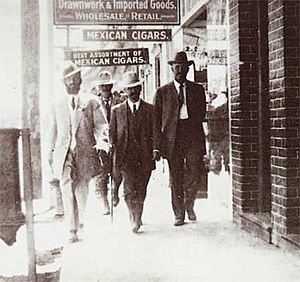

This first part of the Mexican Revolution ended with Díaz leaving for Europe in exile at the end of May 1911. General Victoriano Huerta escorted him to the port of Veracruz. On June 7, 1911, Madero entered Mexico City in triumph. Huge crowds cheered, shouting "¡Viva Madero!"

Madero arrived not as a conquering hero, but as a presidential candidate. He began campaigning for the fall presidential election. He kept almost all of Díaz's political figures and the Federal Army in place. The Federal Army had just been defeated by the revolutionary forces. The Governor of Coahuila, Venustiano Carranza, and Luis Cabrera had strongly advised Madero not to sign the treaty. They felt it gave away the power the revolutionary forces had won. Madero believed that revolutionaries should now act peacefully. He recognized the Federal Army and asked revolutionary forces to disband.

Interim Presidency of De la Barra (May–November 1911)

Even though Madero and his supporters had forced Porfirio Díaz out of power, Madero did not become president in June 1911. Instead, following the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez, he was a candidate for president. He had no official role in the temporary presidency of Francisco León de la Barra, a diplomat and lawyer. The Congress of Mexico remained in place. It was full of people Díaz had chosen for the 1910 election. By doing this, Madero stayed true to his belief in constitutional democracy. However, having members of the Díaz government still in power caused him problems.

The German ambassador to Mexico said that De la Barra wanted to work with the former revolutionaries while also trying to weaken Madero's party. Madero wanted to be a moderate democrat and follow the treaty. But by asking his revolutionary supporters to disarm, he weakened his own base. The Mexican Federal Army, which the revolutionaries had just defeated, remained the country's armed force. Madero argued that revolutionaries should now only use peaceful methods.

In the south, revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata was unsure about disbanding his troops. Especially since the Federal Army from Díaz's time was still mostly intact. Madero traveled south to meet with Zapata. Madero promised Zapata that the land redistribution, which was part of the Plan of San Luis Potosí, would happen when Madero became president.

Madero was now campaigning for president, and he was expected to win. Several landowners from Zapata's state of Morelos took advantage of Madero not being in power yet. They asked President De la Barra and the Congress to return their lands. These lands had been taken by Zapata's revolutionaries. They spread exaggerated stories about Zapata's fighters. De la Barra and the Congress decided to send troops under Victoriano Huerta to stop Zapata's revolutionaries.

Madero again traveled south to urge Zapata to disband his supporters peacefully. But Zapata refused because Huerta's troops were moving towards Yautepec. Zapata's suspicions were correct, as Huerta's soldiers violently entered Yautepec. Madero wrote to De la Barra, saying that Huerta's actions were wrong. He recommended that Zapata's demands be met. However, when Madero left the south, he had not achieved anything. Still, he promised Zapata's followers that things would change once he became president. Most of Zapata's followers had grown suspicious of Madero.

Madero's Presidency (November 1911 – February 1913)

Madero became president in November 1911. He wanted to unite the country. So, he appointed a cabinet that included many of Porfirio Díaz's supporters. His uncle Ernesto Madero became Minister of Finance. A unique fact is that Madero became the first head of state in the world to fly in an airplane shortly after taking office.

Madero could not achieve the unity he wanted. Conservative supporters of Díaz had organized during the temporary presidency. They now strongly opposed Madero's reform plans. Conservatives in the Senate refused to pass the changes he wanted. At the same time, some of Madero's allies criticized him for being too soft on Díaz's supporters. They felt he was not moving fast enough with reforms.

After years of strict control, Mexican newspapers used their new freedom of the press to criticize Madero's performance. Madero's brother, Gustavo A. Madero, noted that "the newspapers bite the hand that took off their muzzle." President Madero refused advice to bring back censorship. The press was especially critical of how Madero handled rebellions that started soon after he became president.

Despite problems, Madero's government had important achievements. These included freedom of the press. He freed political prisoners and ended the death penalty. He stopped the Díaz government's practice of appointing local political bosses. Instead, he set up a system of independent local authorities. State elections were fair. He cared about improving education, creating new schools and workshops. An important step was creating a federal labor department. This department limited the workday to 10 hours and set rules for women's and children's labor. Unions were allowed to organize freely. The Casa del Obrero Mundial ("House of the World Worker"), a labor organization, was founded during his presidency.

Madero upset some of his political supporters when he created a new party, the Constitutionalist Progressive party. He removed Emilio Vázquez Gómez from his cabinet. Emilio was the brother of Francisco Vázquez Gómez, whom Madero had replaced as his vice presidential candidate with Pino Suárez.

Madero made some gestures of reform to those who helped him gain power. But his main goal was a democratic change in power, which was achieved by his election. His supporters were offered small reforms, like creating a Department of Labor. But organized workers and peasants seeking land did not see major changes to their lives.

Rebellions Against Madero

Madero kept the Mexican Federal Army and ordered revolutionary forces to disband. For revolutionaries who felt they were responsible for Díaz's resignation, this was hard to accept. Since Madero did not make immediate, big reforms, he lost control of areas in Morelos and Chihuahua. Several rebellions challenged Madero's presidency before the February 1913 coup that removed him.

Zapatista Rebellion

In Morelos, Emiliano Zapata announced the Plan of Ayala on November 25, 1911. This plan criticized Madero for being slow on land reform and declared the signers in rebellion. Zapata's plan recognized Pascual Orozco as a fellow revolutionary. Madero sent the Federal Army to stop the rebellion, but they failed. For Madero's opponents, this showed he was not an effective leader.

Reyes Rebellion

In December 1911, General Bernardo Reyes started a rebellion in Nuevo León. He had been sent to Europe by Porfirio Díaz because Díaz worried Reyes might challenge him for the presidency. Reyes called for "the people" to rise against Madero. His rebellion failed completely, lasting only eleven days before Reyes surrendered to the Federal Army. Madero decided to trust Pascual Orozco to put down this rebellion. Reyes was sent to a military prison in Mexico City. Madero allowed Reyes special privileges in prison, which let him plan more conspiracies from jail.

Vázquez Gómez Rebellion

Around the same time as Reyes's rebellion, Emilio Vázquez Gómez also started an uprising. Emilio was the brother of Francisco Vázquez Gómez. Emilio gathered supporters in Chihuahua, and several small rebellions against Madero's government broke out in December 1911. Madero sent the Federal Army, and then Orozco, to stop the rebellion. Rebels had captured and looted Ciudad Juárez. Orozco arrived and persuaded the rebels to lay down their arms against Madero. Madero was very happy that Orozco had been so successful.

Orozco Rebellion

The two small rebellions that Orozco stopped in the north again showed his military skills. With the Vázquez Gómez rebellion, he realized he was still popular. Orozco was personally unhappy with how President Madero had treated him once he was in office. He started a rebellion in Chihuahua in March 1912. He had financial support from Luis Terrazas, a former Governor of Chihuahua and the largest landowner in Mexico. Wealthy northern families had opposed Díaz's removal and Madero's presidency. They saw Orozco as a possible ally to remove Madero. Madero's advisors had warned him that Orozco was not trustworthy, but Madero had just seen Orozco's loyalty in stopping the previous rebellions. Orozco's "revolution came as a complete shock to Madero."

Madero sent troops under General José González Salas, the Secretary of War, to stop the rebellion. González Salas was not an experienced general. In the first major fight, Orozco won, defeating the Federal Army. González Salas died after this defeat.

General Victoriano Huerta took control of the federal forces. Huerta was more successful. He defeated Orozco's troops in three major battles, forcing Orozco to flee to the United States in September 1912.

Relations between Huerta and Madero became difficult during this campaign. Pancho Villa, a commander, refused orders from General Huerta. Huerta ordered Villa's execution. But Madero changed the sentence, and Villa was sent to the same prison as Reyes. Villa escaped on Christmas Day 1912. Huerta was angry about Madero saving Villa. After drinking, Huerta talked about making a deal with Orozco to remove Madero. When Mexico's Minister of War heard this, he removed Huerta from command. But Madero stepped in and gave Huerta his command back.

Félix Díaz Rebellion

In October 1912, Félix Díaz (Porfirio Díaz's nephew) started a rebellion in Veracruz. He hoped to use his famous name and get support from the U.S. But even with some U.S. support, Díaz's rebellion failed. No Mexican generals or the general public supported it. Díaz was arrested and imprisoned. He was sentenced to death for his rebellion. However, the Supreme Court of Mexico, whose judges were appointed by former President Díaz, said that Félix Díaz should be imprisoned, not executed. Madero did not interfere with this decision. Díaz was moved to the same prison where Reyes was held. There, the two plotted more conspiracies. Madero was too lenient with the leaders of these coup attempts.

U.S. and the Madero Government

At first, the U.S. was cautiously hopeful about Madero leading the new government. He had kept the Federal Army and the government workers. He had also sent away the revolutionary forces that brought him to power. Madero did not seem to be against the U.S. But his resistance to U.S. pressure on various issues was seen as anti-American by the U.S. government and businesses. He did not keep promises made in his name, perhaps by his brother Gustavo A. Madero, to give Mexico's oil industry to the Standard Oil Company. He refused to meet U.S. demands for payment for lives and property lost, unless it was through a joint commission. He planned to start universal male military service, which would have made Mexico stronger against foreign powers. Also, Madero's removal of limits on labor organizing led to strikes, which affected U.S. companies in Mexico. Madero was firm against demands that interfered with Mexico's independence, just like President Díaz. But the U.S. kept pushing these issues.

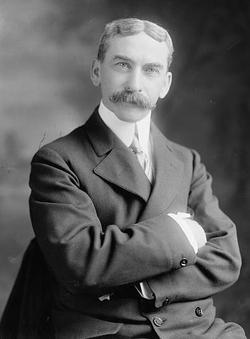

The U.S. attitude towards Madero's government became more hostile. The U.S. Ambassador, Henry Lane Wilson, spread anti-Madero information. This was meant to alarm American residents and create negative stories about Madero in U.S. newspapers. The U.S. government and businesses also increasingly supported rebellions against Madero.

Germany and the Madero Government

Germany had business interests in Mexico. But it did not want to challenge the U.S. as the main foreign power in Mexico. Before World War I started in August 1914, Germany followed the U.S. lead. It was initially optimistic about Madero's moderate approach. But when the U.S. turned against Madero, the U.S. ambassador and the German ambassador, Paul von Hintze, stayed in close contact. Hintze's reports on Mexico during Madero's presidency have been a valuable source of information. Although the U.S. tried to get Germany and Great Britain to intervene in Mexico, both held back. They also tried to stop the U.S. from intervening itself. Hintze had a low opinion of Félix Díaz. He saw the head of the Mexican Federal Army, Victoriano Huerta, as a good choice for a military dictator. This view shaped his actions as a plan for a coup was made in early 1913.

Overthrow and Death of Madero

In early 1913, General Félix Díaz (Porfirio Díaz's nephew) and General Bernardo Reyes planned to overthrow Madero. These events are now known as the Ten Tragic Days in Mexican history. From February 9 to 19, events in the capital led to Madero's overthrow and murder. Rebel forces bombed the National Palace and downtown Mexico City from the military arsenal. Madero's loyalists initially held their ground. But Madero's commander, General Victoriano Huerta, secretly switched sides to support the rebels. Madero's decision to appoint Huerta as commander of forces in Mexico City was a choice "for which he would pay for with his life."

Madero and his vice president were arrested. Under pressure, Madero resigned from the presidency. He expected to go into exile, just as President Díaz had done in May 1911. Madero's brother and advisor Gustavo A. Madero was kidnapped and killed. After Huerta's coup on February 18, 1913, Madero was forced to resign. After serving for only 45 minutes, Pedro Lascuráin was replaced by Huerta, who became president later that day.

After his forced resignation, Madero and his Vice-President José María Pino Suárez were held under guard in the National Palace. On the evening of February 22, they were told they would be moved to the main city prison, where they would be safer. At 11:15 p.m., reporters outside the National Palace saw two cars with Madero and Suárez leave the main gate. They were heavily guarded by soldiers. The cars drove towards the prison. A reporter heard gunshots as he approached the prison. Behind the building, he found the two cars with the bodies of Madero and Suárez nearby. They were surrounded by soldiers. The officer in charge later told reporters that a group had fired on the cars as they neared the prison. He claimed the two prisoners had jumped from the vehicles and ran towards their supposed rescuers. He said they were killed in the cross-fire. Most people did not believe this story.

President Madero, who was 39 years old, was quietly buried in the French cemetery of Mexico City. Only his close family were allowed to attend. They left for Cuba right after. After Huerta was overthrown, Francisco Cárdenas, the officer who killed Madero, fled to Guatemala. He died in 1920 after the new Mexican government asked for him to be sent back to Mexico to face trial for Madero's murder.

Aftermath of the Coup

Madero's murder caused shock. But many Mexican elites and foreign business owners and governments saw the coup and Huerta's rise as a good thing. They wanted a strong leader to bring order back to Mexico. Among Mexico's wealthy, Madero's death was a cause for celebration. They saw the time since Díaz's resignation as unstable. However, ordinary Mexicans in the capital were upset by the coup. Many considered Madero a friend. But their feelings did not lead to action against Huerta's government.

In northern Mexico, Madero's overthrow and death united forces against Huerta. The Governor of Coahuila, Venustiano Carranza, refused to support the new government. He brought together different revolutionary groups under the name of the Mexican Constitution. The Constitutionalist Army fought for the principles of constitutional democracy that Madero believed in. In southern Mexico, Zapata had been rebelling against Madero's government for its slow land reform. He continued to rebel against Huerta's government. However, Zapata no longer thought highly of Pascual Orozco, who had also rebelled against Madero, when Orozco allied with Huerta.

Madero's movement had started the revolutionary action that led to Díaz's resignation. Madero's overthrow and murder during the Ten Tragic Days led to more years of civil war.

For Mexicans who hoped for positive change with Madero's presidency, his time in office was not always inspiring. But as a martyr (someone who dies for a cause) to the revolution, removed and killed by forces against change, with the help of the United States ambassador, he became a powerful symbol. The Governor of Coahuila, Madero's home state, became the leader of the northern revolutionaries opposing Huerta. Venustiano Carranza had been put in office by Madero. Carranza named the broad northern group the Constitutionalist Army. They fought for the Mexican Constitution of 1857 and the rule of law.

By 1917, when the Constitutionalists won the revolution, Carranza began to change the historical story of the revolution. He left Madero out completely. For Carranza, the revolution had three parts, starting with the armed fight against Huerta, led by himself. After three years as president, Carranza himself was overthrown and killed in a 1920 coup. Madero's status as a hero of the revolution was restored by the next group of leaders. November 20, the day Madero set for the rebellion against Porfirio Díaz, became a national holiday.

Historical Memory and Popular Culture

Madero was known as "The Apostle of Democracy." But "Madero the martyr meant more to the soul of Mexico."

Despite Madero's importance, there are relatively few memorials or monuments to him. It was not until the Monument to the Revolution was finished in 1938 that Madero had a public resting place. He had been buried in the French cemetery in Mexico City after his death. His tomb had been a place people visited on the anniversary of his murder (February 22) and the start of the Mexican Revolution (November 20). The monument was planned to honor the Revolution as a whole, not just individual revolutionaries.

November 20, the date of Madero's Plan of San Luis Potosí, was an official holiday in Mexico, Revolution Day. But a 2005 law change made the third Monday in November the day of celebration.

The Mexico City Metro has a stop named for Madero's vice president, Metro Pino Suárez, but not one for Madero himself. A statue of Madero was planned for the main square in Mexico City, but it was never built. A statue was put up in 1956 at a downtown intersection in Mexico City. It has since been moved to the presidential residence, Los Pinos, where the public cannot easily see it.

An exception is Avenida Madero in Mexico City. On December 8, 1914, General Pancho Villa declared that the street leading from the Zócalo (main square) in Mexico City towards the Paseo de la Reforma would be named for Madero. It is still officially called Francisco I. Madero Avenue, but is commonly known simply as Madero street. It is one of the most popular and historic streets in the city. It became a pedestrian-only area in 2009.

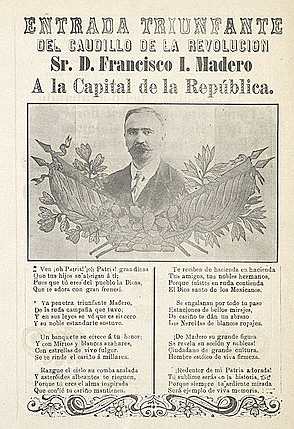

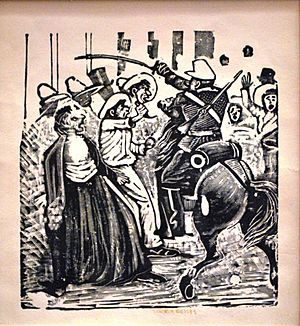

Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada created an etching for a song sheet (called a broadside) when Madero was elected in 1910. It was titled "Calavera de Madero," showing Madero as a calavera (a skeleton figure).

Madero appears in the films Viva Villa! (1934), Villa Rides (1968), and Viva Zapata! (1952). He is also a main character in the novel The Friends of Pancho Villa (1996) by James Carlos Blake.

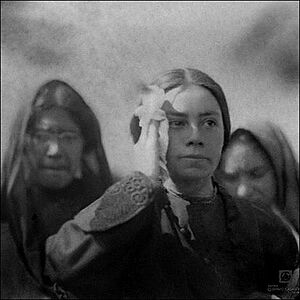

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Francisco I. Madero para niños

In Spanish: Francisco I. Madero para niños

- List of heads of state of Mexico

- Emilio Madero, brother

- Ernesto Madero, uncle

- Gustavo A. Madero, brother

- Manifiesto a la Nación (Francisco I. Madero)