Freedom Train facts for kids

Two special trains called the Freedom Trains have traveled across the United States. The first one, the Freedom Train, toured from 1947 to 1949. The second was the American Freedom Train, which celebrated the United States Bicentennial in 1975–1976.

Each train had its own special red, white, and blue design. They traveled through all 48 states at the time. They stopped in many cities to show important American historical items.

The 1940s Freedom Train allowed both black and white visitors to see the exhibits together. However, some cities like Birmingham, Alabama, and Memphis, Tennessee, wanted to keep visitors separated by race. Because of this, the Freedom Train skipped those cities. This caused a lot of discussion and disagreement.

Contents

The First Freedom Train: 1947–1949

The idea for the first Freedom Train came from Attorney General Tom C. Clark in 1946. He thought Americans were forgetting the importance of freedom after World War II. A group including Paramount Pictures and the Ad Council helped make the idea happen.

What Was the Freedom Train's Message?

The Advertising Council called the Freedom Train a "campaign to sell America to Americans." They planned many events to go with the train. These included messages on radio shows, in comic books, and in movies.

In every city the train visited, they held a "Rededication Week." This was a time for public celebrations of the United States. In 1947, they created the "American Heritage Foundation" to manage the project.

The foundation's leaders included important people from banks and businesses. At first, no African-Americans were on the board. Later, Frederick D. Patterson, who founded the United Negro College Fund, joined in October 1947.

The National Archives provided many important documents for the train. These included the Emancipation Proclamation and a letter from Christopher Columbus. They also showed the Mayflower Compact and documents from World War II. The train focused on creating a shared idea of what it meant to be American.

The exhibits also showed what a "Good Citizen" looked like. For men, it often meant wearing suits. For women, it involved community activities and raising children. The exhibits also linked American freedoms to buying goods and producing many products.

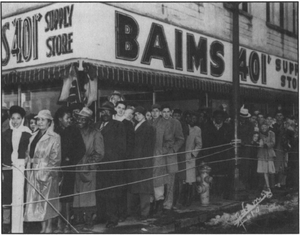

Conflict Over Segregation

When the Freedom Train plan was announced in 1947, it sparked a lot of talk about freedom for Black Americans. Poet Langston Hughes wrote a poem called "Freedom Train." It described the train passing through the segregated Southern states. In these places, black and white passengers had to ride in separate train cars.

The Truman administration decided that the train itself would not be segregated. This meant black and white visitors could see the exhibits together.

However, the mayor of Memphis, Tennessee, James J. Pleasants Jr., said that black and white people would have separate visiting times. The Freedom Train organizers then canceled the train's stop in Memphis. The mayor said separate times were needed to avoid "race trouble."

In Birmingham, Alabama, public safety commissioner Bull Connor insisted on separate lines for black and white visitors. They would take turns entering the train. The American Heritage Foundation, facing pressure from groups like the NAACP, also canceled the train's visit to Birmingham.

Even during the tour, people kept talking about the train. Some newspapers pointed out that despite the "Freedom Train," some citizens still faced discrimination.

The American Freedom Train: 1975–1976

A second freedom train, the American Freedom Train, toured the country in 1975 and 1976. It celebrated the United States Bicentennial, which was America's 200th birthday.

This train had 26 cars and was pulled by three restored steam locomotives. One famous locomotive was the Southern Pacific 4449. This large 4-8-4 steam locomotive still operates today for special trips.

The train had 10 display cars. These cars held more than 500 important American items. Some of these treasures included:

- George Washington's copy of the Constitution.

- The original Louisiana Purchase document.

- Judy Garland's dress from The Wizard of Oz.

- Joe Frazier's boxing trunks.

- Martin Luther King Jr.'s pulpit and robes.

- A rock from the Moon.

The train visited all 48 states from April 1, 1975, to December 31, 1976. More than 7 million Americans visited the train. Millions more watched it pass by from the side of the tracks.

The tour started in Wilmington, Delaware. It traveled northeast to New England, then west through states like Pennsylvania and Ohio. It went around Lake Michigan to Illinois and Wisconsin. From the Midwest, it continued west to Utah and the Pacific Northwest.

The train then went south along the Pacific coast to southern California. For Christmas 1975, the train and its crew were in Pomona, California. They even decorated the locomotive with a Santa Claus picture.

In 1976, the tour continued east through Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. Then it went north to Kansas and Missouri. After that, it traveled through the Gulf Coast states. Finally, it went north again to Pennsylvania and then south along the Atlantic coast. The tour ended on December 26, 1976, in Miami, Florida.

In 1977, the National Museums of Canada bought 15 of the cars. From 1978 to 1980, they toured Canada as the Discovery Train. This was a mobile museum about Canada's history.