Gerrymandering in the United States facts for kids

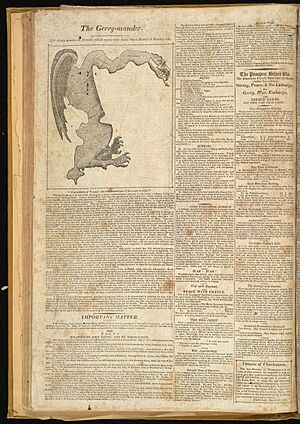

Gerrymandering is a way of drawing the lines of voting districts to give one political party an unfair advantage over another. These districts often end up looking very strange and winding, not like normal, compact areas. The word "gerrymander" came from a cartoon in 1812. It showed a district in Massachusetts that looked like a salamander, and it was drawn by Governor Elbridge Gerry's party.

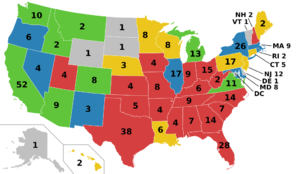

In the United States, district lines are redrawn about every ten years, after the national census. This process, called redistricting, sets the borders for areas where people vote. Each district in a state must be connected and have about the same number of voters. The way these maps are drawn affects who gets elected to the United States House of Representatives and state legislatures.

Redistricting has always been a political process. In most states, state lawmakers and sometimes the governor control it. If one party controls both the state legislature and the governor's office, they can draw district lines to help their party win more elections. Since 2010, powerful computers and detailed maps have made it easier for parties to gerrymander. This helps them keep control for many years, even if the state's population changes. Many people have argued that gerrymandering is unfair and unconstitutional.

There are different types of gerrymandering:

- Partisan gerrymandering: This is when districts are drawn to help one political party and hurt another.

- Bipartisan gerrymandering: This happens when both major parties agree to draw lines that protect the politicians who are already in office.

- Racial gerrymandering: This is when district lines are drawn to reduce the voting power of minority groups.

Sometimes, districts are drawn to increase the number of minority voters in a specific area to help minority candidates win. Other times, the goal is to "pack" minority voters into a few districts, which means their votes are less powerful in other districts.

Courts have said that extreme gerrymandering can be unconstitutional. However, it has been hard for them to decide exactly when it crosses the line. The Supreme Court of the United States has ruled that racial gerrymandering is against the Constitution. But when it comes to partisan gerrymandering (favoring one party), the Supreme Court decided in 2019 that federal courts cannot solve these issues. This means it is up to states and Congress to find ways to stop partisan gerrymandering. Some states have created special independent groups, called redistricting commissions, to draw district lines more fairly.

What is Partisan Gerrymandering?

Partisan gerrymandering is when voting districts are drawn to give one political party an unfair advantage. This practice has a long history in the United States.

How it Started (1789–2000)

The word "gerrymander" was first used in a newspaper in 1812. It was a reaction to how Massachusetts state senate districts were redrawn under Governor Elbridge Gerry. He signed a bill that changed the districts to help his Democratic-Republican Party. When one of the new districts north of Boston was mapped, it looked like a salamander.

No one knows for sure who first said the word "gerrymander." Many historians believe it was newspaper editors who were against Governor Gerry. A political cartoon showing a strange, dragon-like animal with the odd-shaped district helped make the word popular. This cartoon was likely drawn by Elkanah Tisdale. The word quickly spread across the country, describing any time district shapes were changed for political gain.

Over time, other names have been given the "-mander" ending to refer to specific politicians, like "Jerrymander" for California Governor Jerry Brown.

In the 1960s, the Supreme Court ruled that all voting districts must have roughly the same number of people. This led to states redrawing their districts more often, which also increased political fights over how the lines were drawn.

Modern Gerrymandering (2000–2010)

New technology has made gerrymandering easier. Using computers and census data, mapmakers can quickly try out many different ways to draw districts. They can use this to "pack" or "crack" votes.

- Packing votes: This means putting many voters who support the opposing party into one district. This makes sure the opposing party wins that one district by a huge amount, but it also means they have fewer voters spread out in other districts, making it harder for them to win elsewhere.

- Cracking votes: This means spreading out voters who support the opposing party across many districts. This dilutes their voting power in each district, making it harder for them to win any seats.

Both of these methods create "wasted votes," which are votes that do not help a party win. This can be votes that are far more than needed to win a district, or votes for a party that loses.

For example, in Pennsylvania, Republicans redrew a district in 2002 to make it harder for Democratic representative Frank Mascara to win. His new district was so oddly shaped that it included his house but not where he parked his car!

Sometimes, gerrymandering is done along racial lines. In Ohio, a recording showed Republican officials discussing how they moved about 13,000 African-American voters out of a district to help a Republican candidate. This was because African-Americans often vote for Democratic candidates.

International observers from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe criticized the U.S. redistricting process in 2004. They suggested changes to make elections more competitive.

Recent Trends (2010–2020)

Before the 2010 United States elections, the Republican Party started a plan called REDMAP. They realized that the party controlling state legislatures after the 2010 United States Census could draw district maps to keep their power for the next ten years. Republicans won many state elections in 2010, and by 2011 and 2012, many new district maps clearly favored Republicans. This led to many lawsuits.

In 2015, a study looked at drawing maps based on voting-age citizens instead of total population. It found this would help Republicans and non-Hispanic white voters. This study was found after the researcher's death in 2018.

Some state courts have said that partisan gerrymandering is not allowed under their state constitutions. Also, in 2018, several states passed new rules that require non-partisan groups to draw district lines for the 2020 redistricting.

Is Partisan Gerrymandering Legal?

Federal Courts

Courts in the United States have often been asked to rule on partisan gerrymandering, but they have usually avoided making strong decisions. This is because they do not want to seem biased towards one political party.

In 1986, the Supreme Court said that partisan gerrymandering could be unconstitutional. However, the judges could not agree on how to decide when it was unconstitutional. Lower courts found it hard to use this ruling.

In 2004, the Supreme Court looked at partisan gerrymandering again. They still agreed it could be unconstitutional, but again, they could not agree on a clear rule. Justice Anthony Kennedy suggested that lower courts should try to find a way to measure when partisan gerrymandering happens.

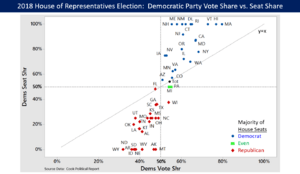

This led to new ideas, like the "efficiency gap" developed around 2014. This method measures "wasted votes" – votes that do not help a party win. If there is a big difference in wasted votes between two parties, it suggests gerrymandering.

The efficiency gap was used in a major court case in 2016, Gill v. Whitford, about Wisconsin's legislative districts. In 2012, Republicans won 60 out of 99 seats, even though Democrats had more total votes statewide. This was seen as a result of gerrymandering. The court found this unfair and a violation of constitutional rights. The case went to the Supreme Court, but it was sent back to a lower court without a final decision on the merits.

Other cases, like Benisek v. Lamone (Maryland) and Rucho v. Common Cause (North Carolina), also dealt with partisan gerrymandering.

However, on June 27, 2019, the Supreme Court made a big decision in Rucho v. Common Cause. They ruled that federal courts cannot decide partisan gerrymandering cases because they are "political questions." This means it is up to Congress and state governments to find ways to stop extreme partisan gerrymandering, for example, by using independent groups to draw districts.

State Courts

Even though federal courts stepped back, some state courts have taken action. The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ruled in 2018 that gerrymandering was unconstitutional in their state. They said it violated the "free and equal" elections rule in Pennsylvania's constitution. When the state government did not redraw the maps, the court did it themselves. The U.S. Supreme Court did not challenge this.

In October 2019, a panel of judges in North Carolina also threw out a gerrymandered election map, saying it was drawn to hurt the Democratic Party.

Bipartisan Gerrymandering

Bipartisan gerrymandering is when both the Democratic and Republican parties work together to draw district lines that protect the politicians who are already in office. This became very common in the 2000s, leading to many elections where the outcome was almost certain before people even voted. The Supreme Court has said that this type of gerrymandering is generally allowed.

Racial Gerrymandering

Racial gerrymandering is when district lines are drawn based on the race of voters. This often overlaps with partisan gerrymandering because minority groups tend to vote for certain parties.

Negative Racial Gerrymandering

"Negative racial gerrymandering" means drawing district lines to stop racial minorities from electing the candidates they prefer. For a long time, especially in the Southern United States, white politicians drew districts to reduce the voting power of African-Americans and other minorities.

After the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed, it became illegal to draw maps that intentionally reduce the power of minority voters. This law was updated in the 1980s to make states redraw maps if they had a discriminatory effect.

Affirmative Racial Gerrymandering

While it is illegal to draw districts to hurt minority voters, sometimes districts are drawn to help them. This is called "affirmative racial gerrymandering." The Supreme Court has said that if a state draws district lines mainly based on race, it must have a very good reason. For example, they might do this to follow the Voting Rights Act.

One famous example was North Carolina's 12th congressional district. It was a very long, narrow district drawn to include many African-American voters. The Supreme Court looked at this district in the case Shaw v. Reno (1993).

In 2001, in the case Easley v. Cromartie, the Supreme Court approved a racially focused gerrymander in North Carolina. They said it was not purely racial but also partisan, which was allowed.

In 2006, the Supreme Court upheld most of a Texas congressional map. This decision allowed state legislatures to redraw districts as often as they want, not just after the census. However, they did say one district was unconstitutional because it harmed an ethnic minority group.

In 2013, a Supreme Court decision made it harder for the federal government to stop racial gerrymandering. This means states have more control over their redistricting.

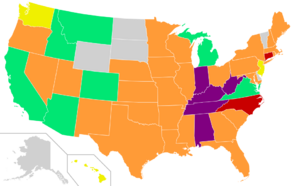

Prisons and Gerrymandering

Since 1790, the United States Census Bureau has counted prisoners as residents of the districts where they are in jail, not where they lived before. In many places, prisoners cannot vote. This means that districts with prisons can have a large number of people counted, even if those people cannot vote there. This can make a district seem larger than it is in terms of active voters.

This practice, called "prison gerrymandering," has been criticized because it can change who gets political power. Since many prisoners are people of color from cities who are jailed in rural areas, counting them in rural districts can take political power away from minority groups in cities and give it to white voters in rural areas.

Reform Efforts

In 2018, the Census Bureau decided to keep counting prisoners where they are jailed. However, they also offered to help states count prisoners at their old addresses for redistricting.

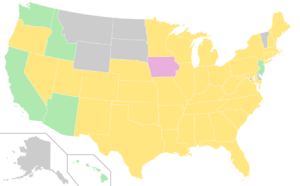

Many states have now passed laws to count incarcerated people at their pre-incarceration homes for redistricting purposes. These include Maryland, New York, California, Delaware, Nevada, Washington, New Jersey, Colorado, Virginia, and Connecticut. Some other states have also passed laws to prevent or allow local governments to avoid prison-based gerrymandering.

Stopping Gerrymandering

People have tried different ways to stop or reduce gerrymandering.

Fair Redistricting Rules

Courts can order a state to redraw its districts if the current plan is unfair or against the law. If the state does not do it, the court can draw the new map itself.

Some states have passed their own laws to prevent gerrymandering. For example, in 2010, Florida passed amendments to its constitution that stop the state legislature from drawing maps that favor or hurt any political party. In 2018, Ohio voters passed a rule that requires new redistricting maps to have at least 50% approval from the minority party in the legislature.

Redistricting Commissions

Some states have created special non-partisan groups, called redistricting commissions, to draw district lines. These groups are supposed to be fair and not favor any party. States like Washington, Arizona, and California have these commissions.

The state of Arizona's legislature challenged the idea of a non-partisan commission. But in 2015, the Supreme Court of the United States said that these commissions are constitutional.

Computer Algorithms

Some people have suggested using computer programs to draw districts. The idea is that a computer could draw districts based on clear rules, without human bias. The challenge is agreeing on the rules for the computer program, as these rules can still affect which party wins.

Computers can also be used to find gerrymandering. An algorithm can compare proposed districts to many other possible maps. If the proposed districts look very different or more extreme than most others, it might mean they are gerrymandered. This kind of analysis has been used in court cases.

Different Voting Systems

The United States mainly uses a "first-past-the-post" voting system, where the person with the most votes in a district wins. Other voting systems could reduce gerrymandering. For example, proportional representation systems, used in many European countries, try to give parties a number of seats that matches their percentage of the total votes. This means if a party gets 30% of the votes, they get roughly 30% of the seats, no matter how the districts are drawn.

Effects of Gerrymandering

On Democracy

Gerrymandering can make elections less competitive. When districts are drawn to favor one party, candidates from the other party might not even bother to run. This can lead to weaker candidates and less money donated to campaigns. It can also make voters less likely to support the targeted party. This means gerrymandering can hurt the health of the democratic process.

On the Environment

Gerrymandering can also create problems for people living in the affected districts. Some studies suggest that partisan gerrymandering can lead to health issues for minority groups. This is because these groups are sometimes "gerrymandered out" of districts that are farther away from toxic waste sites. This could be a deliberate move to make it harder for minority communities to get political representation and fix environmental problems in their areas.

In the 2018 Midterm Elections

Many Democrats felt that gerrymandering was a major problem in the 2018 U.S. midterm elections. Courts in North Carolina and Pennsylvania ruled that Republicans had unconstitutionally gerrymandered districts in those states.

In Pennsylvania, the map was redrawn, which helped Democrats gain more seats in Congress. In North Carolina, the districts were not redrawn before the election. Republicans won 50% of the votes but got about 77% of the seats in Congress, showing a big difference caused by gerrymandering.

| State | % Vote D | % Vote R | % Seats D | % Seats R | Total Seats | Difference Between D | Difference Between R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Carolina | style="background:#CCEEFF" 48.35% | style="background:#FFD0D0" 50.39% | style="background:#CCEEFF" 23.08% | style="background:#FFD0D0" 76.92% | 13 | −25.27% | 26.53% |

| Ohio | style="background:#CCEEFF" 47.27% | style="background:#FFD0D0" 52% | style="background:#CCEEFF" 25% | style="background:#FFD0D0" 75% | 16 | −22.27% | 23% |

Other Factors Affecting Districts

Some people blame gerrymandering for less competitive elections and more political disagreements in Congress. However, others argue that people are increasingly choosing to live near others who share their political views. This "self-segregation" by political ideology might also contribute to less competitive elections, even without gerrymandering. Studies suggest that factors other than gerrymandering account for most of the increase in political polarization.

Examples of Gerrymandered U.S. Districts

|

North Carolina's 12th congressional district (2003-2016) was an example of "packing." It had mostly African-American residents who voted for Democrats. |

| California's 23rd congressional district was a very narrow strip along the coast, designed to "pack" voters. It was redrawn after the 2010 census by California's non-partisan commission. | |

|

California's 11th congressional district had strange, long shapes. It was designed to include people and communities that favored the Republican Party. It was redrawn after the 2010 census. |

|

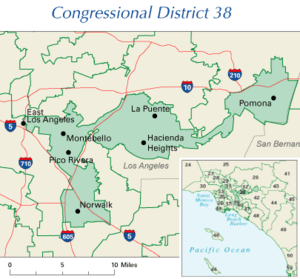

Bipartisan gerrymandering created California's 38th congressional district. This district was home to Democrat Grace Napolitano, who ran unopposed in 2004. It was redrawn after the 2010 census. |

|

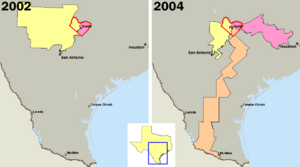

Texas's controversial 2003 gerrymander created Texas District 22 for former Republican Rep. Tom DeLay. This district was "packed" with Republicans and had a very unusual shape. |

|

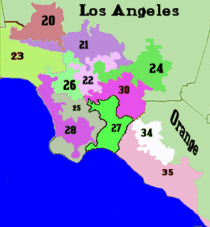

The odd shapes of California Senate districts in southern California (2008) led to complaints of gerrymandering. |

|

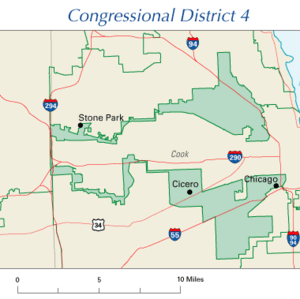

Illinois's 4th congressional district is nicknamed "the earmuffs." It "packs" two mainly Hispanic areas and has a very thin connection between them. |

|

After Democrat Jim Matheson was elected in 2000, the Utah legislature redrew the 2nd congressional district to favor Republicans. The Democratic city of Salt Lake City was connected to Republican areas by a thin strip of land. |

|

Illinois's 17th congressional district in the western part of the state was gerrymandered. Major cities were connected, and Decatur was included, even though it was almost cut off from the main district. |

|

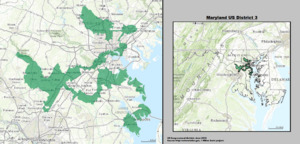

Maryland's 3rd congressional district was called one of the most gerrymandered districts in the U.S. in 2014. It was drawn to help Democratic candidates. |

|

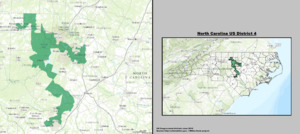

North Carolina's 4th congressional district was considered one of the most gerrymandered districts in the state and the U.S. It included parts of Raleigh, Hillsborough, and all of Chapel Hill. It was redrawn in 2017. |

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |