Government in early modern Scotland facts for kids

Government in early modern Scotland covers how Scotland was ruled from the early 1500s to the mid-1700s. This time period is known as the early modern era in Europe. It started with big changes like the Renaissance (a time of new ideas and art) and the Reformation (when the church changed). It ended with the last Jacobite risings (attempts to bring back the Stuart kings) and the start of the Industrial Revolution.

During this time, Scotland was ruled by kings and queens from the Stuart family, including James IV, Mary Queen of Scots, and James VI. Later, the Hanoverian family took over. The most important part of the government was always the king or queen. Even though some rulers were very young when they started, they tried to make the crown more powerful, like other "new monarchies" in Europe.

Some Scottish thinkers, like George Buchanan, believed in a "limited monarchy," meaning the king's power should have limits. But James VI strongly believed in the "divine right of kings," which meant kings were chosen by God and had special authority. These ideas caused many debates and problems later on.

The king's court was very important for politics and art. The Privy Council and other main government offices helped run the country. Even after the Stuart kings moved to England in 1603, these Scottish offices remained. However, they lost some power and were eventually removed after the Act of Union in 1707, when Scotland was ruled directly from London.

The Parliament was also key. It made laws and decided on taxes. But its power changed a lot over time. It never became as central to national life as the English Parliament before it was also dissolved in 1707.

The Crown's Power

The king or queen was the most important part of the Scottish government. James V was the first Scottish king to wear a closed crown, like an emperor. This showed he believed he had complete power within Scotland. His crown was even rebuilt in 1540 and is now known as the Crown of Scotland. This idea of an "imperial monarchy" meant the crown was a symbol of national unity. It also meant the king was in charge of the law and even the church.

Kings also started to rely on "new men" for advice, instead of just powerful noble families. They used church leaders as civil servants and began to build standing armies and a navy.

One of the most famous thinkers of this time was George Buchanan (1506–82). He wrote books that argued kings should not be tyrants and that people had the right to resist them. Buchanan was one of the teachers of young James VI. Even though James became a very educated prince, he didn't agree with Buchanan's ideas about limited monarchy.

James VI strongly believed in the "Divine Right of Kings." This idea said that a king was chosen by God and had a special, holy power. He passed these ideas on to his son, Charles I. Charles's strong belief in this divine right made it hard for him to compromise, which led to many political problems. When Charles I was executed in 1649, the Scottish Covenanters disagreed with it.

Later, in 1689, when the Scottish leaders needed a reason to remove James VII from the throne, they used Buchanan's ideas. They argued that the king's power came from an agreement with the people, not just from God. This was stated in the Claim of Right.

Important Government Officials

The Chancellor was like the most important minister in the kingdom. His office, called the chancery, was in charge of the Great Seal. This seal was needed for important documents, like transferring land. The Chancellor's main job was to lead meetings of the Privy Council.

The next most important job was the Secretary. This person was responsible for keeping records of the Privy Council and handling foreign policy, including issues with the borders. This job remained important even after the Scottish king also became king of England in 1603.

The Treasurer was in charge of the king's money. At first, there was also a Comptroller, but this job was combined with the Treasurer's in 1610.

Other important officials included the Lord President of the Court of Session, who connected the Privy Council with the main court. The king's advocate was the king's lawyer. This role started in the 1490s and became more important over time, acting as a public prosecutor from 1579.

After Scotland and England united in 1707, most of these offices remained. However, political power shifted more and more to London. The job of Secretary of State for Scotland was even created, but it was later removed in 1746 after a Jacobite uprising.

The Scottish Parliament

In the 1500s, the Scottish Parliament often met in Stirling Castle or the Old Tolbooth, Edinburgh. Mary Queen of Scots had the Old Tolbooth rebuilt in 1561. Later, King Charles I ordered the building of Parliament Hall in Edinburgh. It was built between 1633 and 1639 and was the Parliament's home until it was dissolved in 1707.

Over time, Parliament grew from just the king's advisors (bishops and earls) into a group with political and legal roles. Knights, landowners, and representatives from towns (called burgh commissioners) joined to form the "Three Estates." Parliament gained important powers, like approving taxes. It also had a big say in justice, foreign policy, war, and other laws.

Much of Parliament's work was done by a special committee called the Lords of the Articles. This committee was chosen by the Three Estates to write laws, which were then presented to the full Parliament for approval. Like many parliaments in Europe, the Scottish Parliament met less often in the early 1500s. It might have even disappeared if it hadn't been for several times when young kings were too young to rule, and others had to govern for them.

Parliament played a huge role in the Reformation in the mid-1500s. In 1560, Parliament decided to change the country's religion, even against the king's wishes. This Parliament included many landowners (called lairds) who were mostly Protestant.

After the Reformation, the church's role in Parliament changed. Catholic clergy were excluded after 1567, but a few Protestant bishops continued to be part of Parliament. James VI tried to bring back more bishops around 1600. However, the Covenanters removed them in 1638, making Parliament an assembly of only lay people (non-clergy).

After a period when it was suspended during the time of Oliver Cromwell, Parliament returned when Charles II became king in 1661. This Parliament reversed many of the changes made by the Presbyterians. Because Charles II spent most of his time in England, he used special commissioners to rule Scotland, which weakened Parliament's power.

James VII's Parliament supported him against his enemies. But after he fled into exile in 1689, the next Parliament, led by supporters of William and Mary, effectively removed James from the throne. They did this under the Claim of Right, which offered the crown to William and Mary. This document also placed important limits on the king's power, including getting rid of the Lords of the Articles committee.

Some historians believe that Parliament became a key part of Scottish national life during this time. However, it never reached the same level of importance as the English Parliament. The new Parliament under William and Mary eventually voted for its own end with the Act of Union in 1707. The Scottish and English Parliaments were combined into one Parliament of Great Britain, which met in Westminster (London) and mostly followed English traditions. Forty-five Scottish members joined the House of Commons, and 16 Scots joined the House of Lords.

Images for kids

-

The Stirling Heads, carved wooden decorations on the ceiling of the King's Chamber in Stirling Castle. They show many people from the court of James V.

-

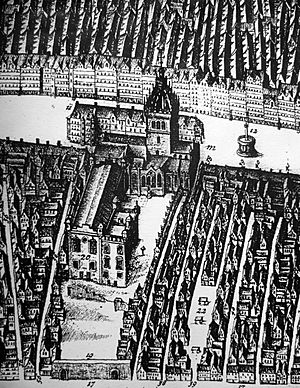

A drawing of Edinburgh in 1544, showing Holyrood Palace, which was called 'the kyng of Skotts palas'.

-

A scene from the Great Window in Parliament Hall, Edinburgh, showing James V starting the Court of Session in 1532.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |