Harkers Island, North Carolina facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Harkers Island, North Carolina

|

|

|---|---|

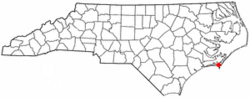

Location of Harkers Island, North Carolina

|

|

| Country | United States |

| State | North Carolina |

| County | Carteret |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3.85 sq mi (9.97 km2) |

| • Land | 2.24 sq mi (5.80 km2) |

| • Water | 1.61 sq mi (4.16 km2) |

| Elevation | 7 ft (2 m) |

| Population

(2020)

|

|

| • Total | 1,127 |

| • Density | 502.90/sq mi (194.15/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code |

28531

|

| Area code(s) | 252 |

| FIPS code | 37-29560 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2402566 |

Harkers Island is a special community in Carteret County, North Carolina, United States. It's called a census-designated place (CDP) because it's a community that the government counts for population, even though it's not officially a town. In 2020, about 1,127 people lived there.

Harkers Island is not an official town, so Carteret County provides most of its services. This includes things like police and schools. The island gets its electricity and water from a special group called a membership cooperative. People on Harkers Island often work in fishing, building boats, or helping tourists. Many also carve beautiful wooden waterfowl decoys.

Long ago, Harkers Island was known by other names like Davers Ile and Craney Island. When the first European explorers arrived in the 1500s, Native Americans from the Coree tribe lived there. The island was first officially owned by Farnifold Green in 1707. Later, in 1730, a man named Ebenezer Harker bought the island. He moved there with his family and started a farm and a boat yard. After he passed away, the island became known as Harkers Island.

In 1899, many people from the Outer Banks moved to Harkers Island. They were escaping a terrible hurricane that destroyed their homes. This made the island's population grow a lot. For a long time, Harkers Island was quite separate from the mainland. Because of this, many residents speak a unique way of English. This special accent earned them the nickname "Hoi toiders."

Contents

Island History: A Journey Through Time

Early Native American Life

Before Europeans came, the Coree tribe lived on Harkers Island. They likely spoke a language similar to other coastal tribes. The nearby Core Sound and Core Banks are named after them. The Coree tribe left behind a large mound of oyster shells at Shell Point. This mound shows they lived and ate seafood there. Similar shell mounds were found on other islands. These mounds were often used for religious or special ceremonies by ancient peoples.

First European Explorers and Maps

In 1584, English explorers, sent by Sir Walter Raleigh, explored the North Carolina coast. They were looking for a good place for a new English colony. Two Native Americans, Wanchese and Manteo, went back to England with the explorers. Some local stories say Wanchese was from Harkers Island.

The island first appeared on maps drawn by John White during this expedition. However, it didn't have a name yet. On a 1624 map by Captain John Smith, the island was called "Davers Ile." This name was probably for Sir John Davers, who helped start Jamestown.

Changing Hands: Early Land Owners

On December 20, 1707, Farnifold Green became the first official owner of land in the Core Sound area. This land included Harkers Island, which was then called Craney Island. Green sold the island to William Brice in 1709. Brice then sold it to Thomas Sparrow III on the same day. Sparrow later sold it to Thomas Pollock, who became governor of North Carolina twice. Pollock didn't live on the island but rented out farm buildings there. His son, George Pollock, inherited the island in 1722.

Ebenezer Harker's Arrival and Family Life

George Pollock sold Craney Island to Ebenezer Harker on September 15, 1730. Harker paid £400 and a boat for the island. Ebenezer Harker had moved to Massachusetts from England. He worked in the whaling business and knew the North Carolina coast well. By 1728, he lived in Beaufort, North Carolina.

After buying the island, Harker moved there with his family. He started a small farm and a boat yard. He later sold half of the island to his nephew, John Stevens. But Stevens eventually sold it back to him. The Harker family grew to include three sons, two daughters, and several enslaved African people. Ebenezer Harker was the last person to own the entire island by himself. When he passed away in 1762, his sons and daughters inherited different parts of the island and some enslaved people. The island was still called "Craney Island" in his will. The name "Harkers Island" was adopted after his death.

Ebenezer's sons did well on the island. Zachariah Harker started a salt works in 1776. The Harker brothers supported the American Revolution. Zachariah became a captain in the local army fighting the British. Harkers Island was even part of a small battle in 1782. Thirteen men on the island stopped British troops from taking supplies. The first national census in 1790 showed 16 white residents and 13 enslaved people on Harkers Island. By 1800, the population had grown to 26 white residents, 16 enslaved people, and 7 "others."

The 1800s: Growth and Change

Harkers Island remained small until the late 1800s. The island did not see direct fighting during the American Civil War. However, Union ships were anchored nearby. After the war, in 1864, the first school on the island opened. A woman named Miss Jenny Bell came from Boston to teach. A factory that made fish oil operated from 1865 to 1873. A small mill for grinding grain was built in 1870 but closed later. Most islanders continued to make a living by building boats or fishing.

The Great Hurricane of 1899

Harkers Island saw many new people arrive after big hurricanes in 1896 and 1899. These storms badly damaged communities on the nearby Core Banks and Shackleford Banks. Many people, mostly fishermen, decided to move. William Henry Guthrie was one of the first to buy land on Harkers Island in 1897.

Three years later, the Hurricane of 1899 completely destroyed Diamond City, a large town on the Shackleford Banks. The storm washed away sand dunes and topsoil. Homes were ruined, and even graves were disturbed. Many families used boats to move parts of their houses, piece by piece, to Harkers Island to rebuild. Some settled on land Guthrie divided, while others bought or rented land. Some moved to Morehead City, where they built a new area called "The Promised Land." By 1902, no one was left in Diamond City. Between 1895 and 1900, the population of Harkers Island grew four times larger, from 13 families to over 1,000 residents. It became one of the biggest communities in Carteret County.

After the hurricanes, leaders from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) visited Harkers Island. Many people who had lost their homes in Diamond City joined the Latter-day Saints. This made them a larger group than the Methodist Episcopal Church, which had started on the island in 1875. There were some difficulties between the groups. In 1906, the LDS meetinghouse was burned down. However, religious services started again in 1909, and a new meetinghouse was built in the 1930s. Today, Harkers Island has one of the highest percentages of Latter-day Saints in North Carolina.

The 1900s: Connecting to the World

Harkers Island slowly became more connected to North Carolina and the rest of the world in the early 1900s. With more people living there, a post office opened in 1904. The first main road, Harkers Island Drive, was built in 1926. It was paved with oyster shells from the old Coree mound. The county paved the road with hard material in 1936.

The road and post office were connected to the mainland by a ferry until the Earl C. Davis Memorial Bridge was built in 1941. This wooden bridge connected Harkers Island to the small town of Straits. Many islanders wanted the bridge to go to Beaufort, a larger city with hospitals and businesses. But the shorter distance to Straits likely decided the bridge's location. A new steel bridge replaced the wooden one in 1966.

The 1933 Outer Banks Hurricane changed Harkers Island's economy forever. The storm created a new channel between the Core Banks and the Shackleford Banks. This new channel, called Barden Inlet, gave Harkers Island fishermen direct access to fishing areas offshore. This was a big help for their work.

More jobs came to the island as the country recovered from the Great Depression. Electricity arrived in 1939. The Harkers Island Rural Electric Authority was the first electric company in the US to use underwater cables to provide power. In 1941, a new Marine Corps Air Station was built at Cherry Point, bringing more jobs. During World War II, Harkers Island was on the front lines. German submarines patrolled the coast, and island residents could see burning oil tankers offshore at night. Telephone service finally arrived in 1948.

The National Seashore and Its Impact

The Shackleford Banks were very important to Harkers Island's economy for much of the 1900s. Islanders used the Banks to graze their animals, like sheep, goats, cattle, and horses. Fishermen from Harkers Island also built camps and cottages there. They even rounded up wild horses on the Banks each spring. Islanders saw these activities as part of their way of life and how they made money.

However, things changed when the government decided to buy the barrier islands for public park land. North Carolina began buying land in 1959 to create a state park. The federal government also became interested, wanting to create a string of national seashores along the Atlantic coast. In 1966, President Lyndon Baines Johnson signed a law creating the Cape Lookout National Seashore.

Turning the Banks into a national park caused problems for Harkers Island. Many fishermen found that their cottages and other buildings on the Banks were on land the government would take over. Many land records had mistakes, and natural changes to the shoreline affected claims. Few people owned the land where they had built their cottages. Legal battles lasted into the 1980s. The park also ended the grazing of livestock on the Banks by 1985. A herd of wild horses, thought to be from Spanish shipwrecks, was allowed to stay. In late 1985, a series of fires destroyed many buildings on the Shackleford Banks, including a new park visitor center. The cause of these fires was never found.

The creation of the National Seashore changed the way of life for many Harkers Island residents. Fishing and boat building are still important, but tourism is growing. Visitors come to Harkers Island to visit the National Seashore, go sport fishing, and experience the island's unique culture.

Island Geography: Where is Harkers Island?

Harkers Island is located in the southern part of Carteret County. The entire island and some of the surrounding water make up the Harkers Island census-designated place. The total area is about 3.85 square miles (9.97 square kilometers). About 2.24 square miles (5.8 square kilometers) is land, and 1.61 square miles (4.16 square kilometers) is water. The highest point on the island is about 19 feet (5.8 meters) above sea level. This area is known as the "sand hole" and has white sand dunes.

Harkers Island is protected from the Atlantic Ocean by other islands. The Shackleford Banks are to the south, and the Core Banks are to the east. The water directly south of the island is Back Sound. To the east is Core Sound, and to the north is The Straits. The mouth of the North River is to the northwest. The Straits are shallow but boats can travel through them if they know the area. There are two small bays on the north side of the island: Westmouth Bay and Eastmouth Bay. North of Eastmouth Bay is Browns Island, which you can only reach by boat. Harkers Island Road, also called State Road 1335, connects the island to the mainland. It crosses the Earl C. Davis Memorial Bridge, a steel swing bridge built in 1968.

Island Economy: How People Make a Living

The main ways people make a living on Harkers Island are fishing, building boats, tourism, and carving waterfowl decoys. In 2013, there were 22 businesses on the island, employing 107 people. Most of these businesses were in retail and food services, or in construction, manufacturing, and storage. The latter group is mostly related to building, repairing, and storing boats. Many island residents also work for themselves in the fishing industry. A large number of people on the island are over 65 or retired.

Commercial fishing has always been a key part of the island's economy. In the past, this included hunting whales and dolphins. Before ice became available in the 1920s, people mostly caught mullet fish. They would catch them near the beaches and salt them on shore. In the late 1800s, the Core Sound area produced 80% of the salted mullet sold on the US East Coast. An ice plant was built in nearby Beaufort in 1920. This allowed fish houses to open on the island to process fish and shellfish. Some areas on the north side of the island are now used to grow shellfish. Besides mullet, Harkers Island fishermen catch oysters, clams, shrimp, scallops, crabs, spot, croaker, trout, flounder, bluefish, and mackerel.

Tourism is becoming more important for the local economy. The National Park Service has a Visitors Center on Harkers Island for the Cape Lookout National Seashore. Ferries from Harkers Island are a main way for tourists to reach Cape Lookout and the Shackleford Banks. Companies that offer big-game fishing trips are also growing. Other tourism businesses include gift shops, local artists, hotels, and restaurants. Even with this growth, Harkers Island still has fewer tourist facilities compared to other places on the Crystal Coast.

One of the fastest-growing industries is tourism for waterfowl fans. The Core Sound Decoy Carvers Guild started in 1987. They held their first annual festival in December 1998, which attracted 1,800 people. This event, now called the Core Sound Decoy Festival, has brought over 10,000 tourists to Harkers Island. The Core Sound Waterfowl Museum is also a major attraction all year round. It's a large building that tells the history of local waterfowl and decoy carving. The museum also has exhibits about local history. It hosts events during Waterfowl Weekend, which is held at the same time as the Decoy Festival. This festival weekend is the most important event for Harkers Island's tourism economy each year.

Island Population: Who Lives Here?

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 2000 | 1,525 | — | |

| 2010 | 1,207 | −20.9% | |

| 2020 | 1,127 | −6.6% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census | |||

In 2000, there were 1,525 people living on Harkers Island. There were 661 households, and 497 of those were families. The population density was about 598 people per square mile. Most of the people living there were White (98.56%). A small number were Native American, Asian, or from other races.

About 21.6% of households had children under 18. Most households (67.9%) were married couples living together. The average household had 2.30 people, and the average family had 2.65 people.

The population had a wide range of ages. About 15.3% were under 18, and 21.8% were 65 or older. The average age was 49 years old. The median income for a household was $33,125, and for a family, it was $35,492. About 15.5% of the population lived below the poverty line.

Local Dialect: The "Hoi Toider" Talk

Because Harkers Island was separated from the mainland for so long, its residents developed a unique way of speaking English. This special dialect is often called "Hoi toider" and can also be heard on other Outer Banks islands like Ocracoke. It has roots in the way English was spoken during the Elizabethan period. The dialect survived because the community continued to rely on traditional jobs like fishing and boat building. Tourism developed later on Harkers Island than on other islands.

The way people pronounce words in Harkers Island English can be different. For example, "high tide" might sound like "hoi toide." "Time" sounds like "toime," and "fish" sounds like "feesh." "Fire" might sound like "far," and "cape" like "ca'e." Words with "oi" often sound like "er," so "toilet" might sound like "terlet." Words with a short "a" might sound like "schwa," so "crabs" become "crebs." Words starting with "i" often get an "h" sound at the beginning, so "it" becomes "hit." Words ending in a vowel sometimes get an "r" sound added. The old word for a porch, "piazza," becomes "poyzer."

So, you might hear phrases like: "Hit's so hot the blue crebs hev come up on the poyzer to git in the shade." Or, "hit was so rough there were whiteceps in the terlet." Another phrase is "The ersters hev arroived." A large fish with a big fin is called a "sherk." The island dialect also uses old words that are not common anymore. For example, "mommick" means to frustrate, "yethy" describes a stale smell, and "nicket" means a small pinch of something. Islanders also have unique local words. A "dingbatter" is a visitor or someone new to the island. "Dit-dot" is a funny term for a visitor who has trouble understanding the local dialect.

About 500 islanders on Harkers Island are direct descendants of the original settlers who developed this special dialect. Language experts from universities like North Carolina State University and East Carolina University continue to study the island's unique way of speaking.

Education: Learning on the Island

Harkers Island is part of the Carteret County Schools district. Children living on the island go to Harkers Island Elementary School. For middle school, they attend Down East Middle School @ Smyrna. High school students go to East Carteret High School.

Religion: Places of Worship

In 2006, Harkers Island had eight Christian churches. These included the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Free Grace Wesleyan Church, Grace Holiness Church, Harkers Island Pentecostal Holiness Church, Harkers Island United Methodist Church, Huggins Memorial Baptist Church Parsonage, the Lighthouse Chapel (non-denominational), and the Refuge Fellowship Church (non-denominational).

See also

In Spanish: Harkers Island para niños

In Spanish: Harkers Island para niños