Haughmond Abbey facts for kids

Haughmond Abbey (pronounced HOH-mənd) is a ruined medieval monastery near Shrewsbury, England. It was home to Augustinian monks, also called canons. The abbey was likely started in the early 1100s. It was closely connected to the powerful FitzAlan family, who later became the Earls of Arundel. Many wealthy families also supported it.

For most of its 400 years, Haughmond Abbey was a large, successful, and rich monastery. However, some problems appeared before it was closed down in 1539. After it closed, the buildings fell apart, and the church was mostly destroyed. But parts of the living areas still stand and are impressive. Today, English Heritage looks after the site. You can visit it during the summer months.

Contents

How Haughmond Abbey Started

Historians believe Haughmond Abbey was founded sometime between 1100 and 1138. An old book from the abbey, called a cartulary (a collection of important documents), says it was founded in 1100. It credits William FitzAlan as the founder. Two official letters from Pope Alexander III in 1172 also called him the founder.

However, some historians, like R. W. Eyton, found that the dates didn't quite match up. William FitzAlan was very young in 1138. Another local record from the 1200s says the abbey started in 1110.

One of the oldest documents shows William FitzAlan giving the community a fishing spot in the River Severn around 1135. This document mentions Prior Fulk, who was the leader of the community. It also says the monastery was dedicated to Saint John the Evangelist. This dedication lasted throughout the abbey's history. You can still see a carving of St. John with his eagle symbol in the abbey's chapter house.

It's possible that the abbey started even earlier. Some stories say there was a small hermitage (a place for hermits) or chapel there before the abbey was built. William FitzAlan's father, Alan fitz Flaad, was a powerful lord who gained control of the land where the abbey stands around 1109 or 1114. He might have started the community, or it could have been a small group of hermits before his time.

Even if William FitzAlan wasn't the very first person to start the community, he definitely made sure it became strong and successful.

Early Growth and Support

William FitzAlan supported Empress Matilda during a civil war in England. Because of this, he was forced to leave the area from 1138 until about 1153. But even while he was away, the abbey continued to receive gifts.

Empress Matilda gave Haughmond Abbey land and a mill. The abbey was smart and also got King Stephen's approval for these gifts. When Henry, Duke of Normandy (who later became King Henry II), came to England in 1153, he also confirmed these gifts. This was a clever way for the abbey to protect its property no matter who won the civil war.

Another early supporter was Ranulf de Gernon, 4th Earl of Chester. He gave the abbey the right to fish in the River Dee and get thousands of salted fish without paying taxes. This led to gifts of some Welsh churches to the abbey.

In 1155, William FitzAlan got his lands back. He then gave the church at Wroxeter to Haughmond. This church had several priests who shared its income. FitzAlan wanted the abbot to keep five priests at Wroxeter and send five canons (monks) from Haughmond to help with special church services. This showed that the abbey was growing in size and importance, as it was now called the "Abbot of Haughmond."

As the abbey became wealthier, the monks began rebuilding their church and other buildings. They used a style called late Romanesque architecture. The FitzAlan family and their supporters, especially the Lestrange family, paid for most of this work. King Henry II also helped by giving them land around the abbey. This showed that the abbey was closely linked to the royal family.

In the 1160s, Alured, the king's former teacher, became the abbot. In 1172, he got two important letters from Pope Alexander III. These letters confirmed all the early gifts to the abbey. They also gave the abbey special status, allowing them to bury anyone who wished to be buried there. Most importantly, the canons gained the right to choose their own abbot.

Gifts and Supporters

Haughmond Abbey became rich because many people gave it land, churches, and other valuable things. Most of these gifts were in Shropshire, the county where the abbey was located. This was a big advantage because it meant the abbey didn't have to spend a lot of money traveling to manage properties far away.

Here are some of the important properties given to Haughmond Abbey in its first 100 years:

| Location | Donor | Type of Gift |

|---|---|---|

| Preston Boats | William FitzAlan | Fishing rights in River Severn |

| Haughmond | William FitzAlan | The land where the abbey was built |

| Sheriffhales, Shropshire | William FitzAlan | Land |

| Peppering, near Arundel, Sussex | William FitzAlan | Land |

| Walcot, Shropshire | Empress Matilda, confirmed by Stephen and Henry II | Land and a mill |

| River Dee | Ranulf de Gernon, 4th Earl of Chester | Fishing rights |

| Trefeglwys | Church of St Michael | |

| Nefyn | Cadwaladr ap Gruffydd | Church of St Mary |

| Wroxeter | William FitzAlan | St Andrew's Church, Wroxeter |

| Cheswardine | John Lestrange | Mill and Church of St Swithun |

| Shawbury | Robert FitzNigel | Church of St Mary |

| North Stoke, West Sussex | William FitzAlan | St Mary the Virgin's Church, North Stoke |

| Leebotwood, Shropshire | Henry II | Land |

| Betchcott, Shropshire | Henry II | Land |

| Downton, Shropshire | William FitzAlan | Lordship (control over land) |

| Upton Magna, Shropshire | William FitzAlan | Land and a mill |

| Nantwich, Cheshire | William FitzAlan | Half of a salt-making pond |

| Berrington, Shropshire | John Lestrange | Land |

| Webscott, near Myddle, Shropshire | John Lestrange | Land |

| Ruyton-XI-Towns, Shropshire | John Lestrange | Mill and church |

| Myddle, Shropshire | John Lestrange | Mill |

| Nagington, Child's Ercall, Shropshire | Hamo Lestrange | Landed estate |

| Alveley, Shropshire | Guy Lestrange | Mill |

| Wolston, Warwickshire | Guy Lestrange | Mill |

| Hopley, near Hodnet, Shropshire | Osbert of Hopton and Helias de Say | Landed estate |

| Hopton, near Hodnet | Osbert of Hopton and Helias de Say | Half a virgate of land (a measure of land) |

| Hadnall, Shropshire | Gilbert de Hadnall | Land |

| Hardwick, Shropshire | Land | |

| Sundorne, Shropshire | Alan FitzOliver | Landed estate |

| Uffington, Shropshire | Richard de la Mare | Land |

| Withington, Shropshire | Roger FitzHenry | Land |

| Grinshill, Shropshire | Adam de Orleton and others | Land and later control, gained from Wombridge Priory |

| Stockett by Ellesmere, Shropshire | Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd | Landed estate |

| Newton by Ellesmere, Shropshire | Geoffrey de Vere and Robert FitzAer | Land |

| Beobridge, Shropshire | Emma, daughter of Reynold of Pulverbatch | Land |

| Aston Abbots, Shropshire | Amelia de Sibton and others | Land |

Churches were a very important source of money for the abbey. By taking over churches, the abbey received the tithes (a portion of income) from the local people. They could also choose the priests for these churches, which brought in more money. This was a steady income with little effort.

Here are some other churches Haughmond Abbey later took over:

| Location of Church | Dedication |

|---|---|

| Old Hunstanton | St Mary |

| Stokesay | John the Baptist |

| Hanmer | St Chad |

| Stanton upon Hine Heath | St Andrew |

The abbey often tried to get land that was close to its existing properties. This made it easier to manage everything. For example, they built up a large area of land beyond Leebotwood. This land was mostly empty at first but became excellent pasture for cattle.

The abbey also made money from mills. By the 1500s, profits from their 21 grain mills and 5 fulling mills (used for processing cloth) made up about 8% of their total income.

The FitzAlan family was very important to the abbey. They were always seen as the founders. For over 150 years, many members of the FitzAlan family were buried at Haughmond. Even after they became the Earls of Arundel in 1243, they still thought of the abbey as "theirs."

Other families, like the Lestranges, also gave many gifts to the abbey. They continued to support and protect the abbey for centuries.

Ranton Priory and Other Connections

Ranton Priory in Staffordshire was the only monastery that officially depended on Haughmond Abbey. It was founded in the mid-1100s. Its founding document said it was "under the rule and obedience of Haughmond Church." This meant Haughmond was its "mother house."

However, there might have been some disagreements. Later documents show that Ranton Priory wanted more independence. After a special investigation, Ranton Priory was given full independence. But it still had to pay Haughmond Abbey 100 shillings each year.

Haughmond also had spiritual influence over other places. The monks of Owston Abbey in Leicestershire were told to live "according to the order of the church of Haughmond." This meant they should follow Haughmond's strict example of the Augustinian rule.

Life at the Abbey

The Augustinian rule allowed for different ways of living a religious life. Haughmond was a community of Canons Regular, which means they were priests who lived together under a rule. A monastery that was financially stable usually had a better religious life, and Haughmond was generally well-managed. After the mid-1300s, there were usually no more than 13 canons, though the buildings suggest there were many more in earlier times.

At first, the canons at Haughmond wore white robes, which earned them the name Canonici Albi (White Canons). This might suggest that Haughmond started as a small, independent community. However, a local record says that in 1234, Haughmond adopted the typical black robes of the Augustinian order.

Augustinian canons were expected to follow strict rules. They needed permission from their abbot to travel and were never supposed to sleep alone. Because Haughmond's lands were mostly close by, the canons didn't have to travel as much as those from other abbeys. This made it easier to follow the rules.

The food at Haughmond Abbey seems to have been quite varied. In 1280, the abbey received 147 sheep and a calf. They also had fishing rights and bought thousands of salted herrings each year. In the early 1300s, Abbot Nicholas of Longnor made changes to improve the food. He set aside money from certain churches and fisheries to buy meat and fish. He also had a new kitchen built and ordered that the abbey should keep 20 pigs for their larder (food storage).

- Sculptures of the saints at Haughmond Abbey

The art at the abbey tells us about the values of the community. In the 1300s, statues of saints were carved on the arches of the church and chapter house. St Peter and St Paul were placed at the church entrance. These saints were important because they were linked to the Pope, who gave the Augustinian order its authority. Inside the chapter house, there were statues of Augustine of Hippo (the order's namesake) and St John the Evangelist (the abbey's patron saint). Other statues showed saints who were martyrs or known for their spiritual strength, like Thomas Becket, Catherine of Alexandria, John the Baptist, Margaret of Antioch, St Winifred, and St Michael the Archangel.

Books and Learning

The abbey had a library, which Abbot Richard Pontesbury said needed repairs in 1518. A few of their books have survived, including a Bible and works by important French theologians.

John Audelay was a famous writer who lived at Haughmond in the 1400s. He was blind and deaf and worked as a priest for the Lestrange family. His poems often talked about Christian beliefs and church services. He was against the Lollards, a group that had different religious ideas. Audelay's writings give us a good look into the spiritual concerns of that time.

In the 1400s, Haughmond Abbey helped support an Augustinian study house at Oxford University, which later became St Mary's College. The abbey was supposed to send at least one canon to university. However, in 1511, they were fined for not doing so. The only Haughmond canon who became a well-known scholar was John Ludlow, who later became the abbot of Haughmond in 1464.

The Abbey's End and What Happened Next

In 1535, a survey called the Valor Ecclesiasticus estimated Haughmond Abbey's value at about £260 per year. By 1539, its actual income was over £350. At this time, King Henry VIII was closing down monasteries across England. Haughmond Abbey was wealthy enough that it didn't have to close in the first wave. However, many successful monasteries felt pressured to surrender.

Haughmond Abbey officially surrendered in 1539. The abbot, Thomas Corveser, the prior, John Colfox, and nine canons signed a document on October 16, 1539. They recognized Henry VIII as the head of the Church of England. Each of them received a good yearly payment (a pension).

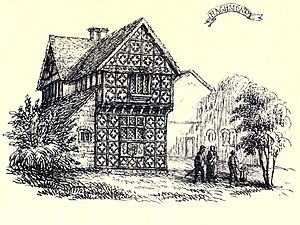

In 1540, the abbey site was sold to Sir Edward Littleton. He then sold it to Sir Rowland Hill, who later sold it to the Barker family. The abbot's hall and nearby rooms were turned into a private home. Sadly, the church and dormitory were torn down, and their stones were used for other buildings.

During the English Civil War, there was a fire at the abbey. After that, it was used as a farm. Today, English Heritage cares for the site. They have a small museum there, and you can visit during opening hours in the summer.

Burials at the Abbey

Many important people were buried at Haughmond Abbey, especially members of the FitzAlan family:

- John FitzAlan, 6th Earl of Arundel

- Maud de Verdon, his wife

- John FitzAlan, 7th Earl of Arundel

- Isabella Mortimer, Countess of Arundel

- Richard FitzAlan, 8th Earl of Arundel

- Alice of Saluzzo, Countess of Arundel

- Edmund FitzAlan, 9th Earl of Arundel

- Alice de Warenne, Countess of Arundel

The Ruins Today

- Extant ruins of Haughmond Abbey

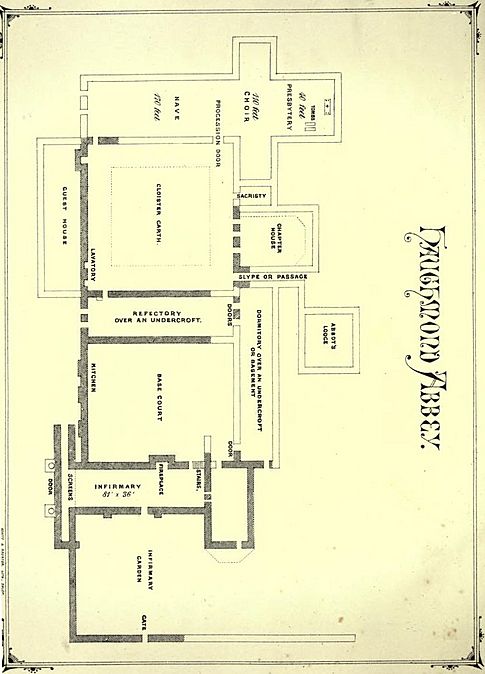

The buildings at Haughmond Abbey were mostly made of white sandstone and red sandstone. Most of the buildings were built around two cloisters (open courtyards). What remains today includes:

- The foundations and a doorway of the church.

- The chapter house from the late 1100s, which still has its roof.

- Walls of the warming house, dormitory, and dining hall.

- Parts of the infirmary (hospital) and the abbot's lodging.

The church itself is mostly gone, but you can still see its cross-shaped outline on the ground. The abbey site would have been surrounded by a ditch, but it's no longer visible. There are also remains of fish ponds and other features from the Middle Ages.

Today, you enter the abbey site from the south. Here, you'll see the impressive, decorated bay window of the abbot's private rooms. This window was added in the late 1400s, showing how the abbots' living spaces became more luxurious over time. The large abbot's hall, with its big west window, was built in the 1300s.

On the western side of the ruins, you can see the walls of the kitchen and dining areas. You can also walk through the entrance to the undercroft of the frater (dining hall). This was the main storage area for food. The kitchen had large fireplaces, which are still very clear. The frater itself was on the upper floor and is now gone.

The main cloister was a large, open area. It led to important parts of the abbey, like the dining hall, chapter house, dormitory, and the church.

The chapter house is very well preserved. It has three beautifully decorated arches from the late 1200s. The middle arch was a doorway, and the side arches were windows. The chapter house was partly rebuilt in the 1500s. It still has an impressive wooden ceiling, which might have been moved from another part of the abbey.

The church is the most ruined part of the site. Only a few walls remain standing. A single Norman arched doorway leads from the cloister into the church. This doorway has beautiful carvings of St Peter and St Paul. The church was about 60 meters (200 feet) long. The ground sloped upwards to the east, so steps led from the nave (main part of the church) to the choir, and then more steps to the sanctuary and high altar. This created a feeling of spiritual ascent.

The remains of the canons' dorter (dormitory) are small. It was probably a two-story building. The bottom floor was used for storage and a warming house. At the north end of the dormitory was Longnor's Garden, where the abbot grew herbs. At the south end, a doorway led to the reredorter, which was the communal washing and latrine area. You can still see a clear stone drain there, which was supplied by a diverted stream.

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |