History of Bahrain (1783–1971) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Bahrain and Its Dependencies

البحرين وتوابعها

al-Baḥrayn wa Tawābi‘hu |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1783–1971 | |||||||||||

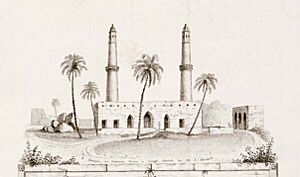

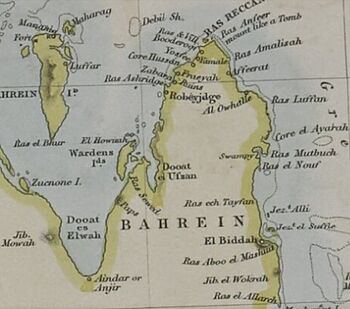

Territory controlled by Bahrain in 1849

|

|||||||||||

| Status | Protectorate of the United Kingdom (1861–1971) | ||||||||||

| Capital | Muharraq (1783–1921)

Manama (from 1921) |

||||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic | ||||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Authoritarian absolute monarchy under a caretaker government | ||||||||||

| Hakim | |||||||||||

|

• 1783–1796

|

Ahmed ibn Muhammad ibn Khalifa | ||||||||||

|

• 1961–1971

|

Isa bin Salman Al Khalifa | ||||||||||

| Chief Political Resident | |||||||||||

|

• 1861–1862

|

James Felix Jones | ||||||||||

|

• 1970–1971

|

Geoffrey Arthur | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period / Cold War | ||||||||||

|

• Established

|

23 July 1783 | ||||||||||

|

• British protectorate

|

31 May 1861 | ||||||||||

|

• Qatari–Bahraini War

|

1867–1868 | ||||||||||

|

• Independence

|

15 August 1971 | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

|

• 1941

|

89,970 | ||||||||||

|

• 1959

|

143,135 | ||||||||||

|

• 1971

|

216,078 | ||||||||||

| Currency | British Indian rupee (19th century–1947) Indian rupee (1947–1959) Gulf rupee (1959–1965) Bahraini dinar (1965–1971) |

||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | BH | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Today part of | Bahrain Qatar |

||||||||||

This article tells the story of Bahrain from 1783 to 1971. It covers the time when the Al Khalifa family first took control until Bahrain became an independent country, no longer ruled by the British Empire.

In 1783, Bahrain was part of the Persian Empire. That year, the Bani Utbah tribe, led by the Al Khalifa family, took over Bahrain. They came from Al Zubarah in what is now Qatar. Their leader, Ahmed bin Muhammad, became known as the conqueror. For the next 75 years, his family faced many challenges but kept control of Bahrain.

Bahrain was often threatened by Oman and the Wahhabis, who even ruled it for short periods. The Persians and Ottomans also claimed the country. In 1820 and 1861, Britain signed peace treaties with Bahrain. These treaties recognized the Al Khalifa family as the rightful rulers.

In 1867, a war broke out between Bahrain and Qatar. Britain stepped in, and Qatar became independent from Bahrain. The British then chose a new Al Khalifa ruler, Isa bin Ali. During his rule (1869–1923), Britain protected Bahrain from outside threats. Isa and his family had absolute power. They treated people as subjects and controlled much of the land like personal property. The money collected from taxes and rents was the ruler's private income. A special group of fighters helped the ruler enforce his orders.

The main parts of Bahrain's economy were growing palms, fishing, and pearl diving. The Al Khalifa family closely controlled palm farming, which was mostly done by the Shia community. However, they were more relaxed about pearl diving. This was controlled by Sunni tribes who had a lot of freedom and resisted interference.

By the late 1800s, Britain made Bahrain a protectorate. This meant Britain protected Bahrain but also controlled its foreign affairs. After World War I, Britain started making changes in Bahrain. These changes, known as the "reforms of the twenties," were about how the government was run. The Shia community supported these reforms, but Sunni tribes and some of the ruling family did not. There was a lot of disagreement and even violence. Britain stepped in again and replaced the ruler with his son, Hamad bin Isa, who supported the changes.

The reforms affected the pearl industry, private land ownership, the justice system, policing, and education. In 1932, oil was discovered in Bahrain. This led to huge economic and social changes. The oil industry soon replaced pearl diving and palm farming as the main parts of the economy.

Contents

Rise of Al Khalifa Family

The Al Khalifa family is a Sunni family. They are part of the Bani Utbah tribe. In 1766, they settled in Al Zubarah in Qatar, after moving from Kuwait. Their ancestors were forced out of Umm Qasr in Iraq by the Ottomans. This was because they often attacked trade caravans and ships. They were exiled to Kuwait in 1716 and stayed there until 1766.

Around the 1760s, the Al Khalifa family moved to Zubarah in modern-day Qatar. The Al Jalahma family, also part of the Bani Utbah tribe, joined them in Al Zubara. This left the Al Sabah family as the only rulers of Kuwait.

However, the Al Khalifa and Al Jalahma families later disagreed about how to share money. The Al Jalahma family moved to Reveish, just east of Al Zubara. The Al Khalifa family attacked them there and killed their leader, Jaber Al Jalahma.

Al Khalifa Rule (1783–1869)

Ahmed's rule (1783–1796) was peaceful. During this time, pearl production and trade grew a lot. But over the next 75 years, the Al Khalifa family faced serious threats. These threats came from both inside and outside Bahrain. Still, they managed to keep control by making alliances with their enemies.

Outside Challenges

In 1796, the Wahhabis took over Al Zubara. This happened after they captured Al-Hasa the year before. Salman bin Ahmed, who took over after his father, moved to Jaww on Bahrain's eastern coast. He later moved to Riffa and built an impressive fort there. In 1799, the ruler of Muscat, Oman attacked Bahrain but failed to control it. The next year, he attacked again and succeeded. He appointed his son to oversee the island.

In 1801, the Al Khalifa family, who had fled to Al Zubara, took back control of Bahrain. They took advantage of the Omani fleet being away. The Omanis fought back the next year but were defeated. The Wahhabis supported the Al Khalifa family against Oman. They protected Bahrain between 1803 and 1809 and directly controlled it in 1810.

As the Wahhabis became weaker in 1811, the Al Khalifa family allied with Oman. They paid tribute to Oman for two years. Then, when Oman was weakened, the Al Khalifa family declared their independence. Rahmah bin Jabir, a leader of the Al Jalahma family, was based in Khur Hassan. He strongly opposed the Al Khalifa family. He attacked their ships and supported their enemies. He was killed in a dramatic battle in 1826.

In 1820, representatives from the British Empire signed a "General Treaty of Peace" with tribal chiefs, including the Al Khalifa. By signing this treaty, the British recognized the Al Khalifa as the "legitimate" rulers of Bahrain. However, they also gave Persia a claim over Bahrain. Persia continued to claim Bahrain until its independence in 1971.

During this time, Oman was the main threat to Bahrain, not Persia. Between 1816 and 1828, Oman launched four military attacks on Bahrain. All of them failed, and the last one caused them huge losses. During the rule of Muhammad bin Khalifa (1843–1868), threats came from the Wahhabis, Ottomans, and Persians. Muhammad tried to please both the Ottomans and Persians by pretending to support them. For the Wahhabis, he used military force. Britain opposed this and secretly offered to defend Bahrain. When Muhammad refused to stop his campaign, Britain stepped in. They surrounded his war fleet and forced him to stop the attack.

The British blockade ended with the signing of the Perpetual Truce of Peace and Friendship in 1861. This agreement stated that Bahrain's ruler would not engage in "war, piracy, and slavery at sea." In return, Britain would provide protection. Britain then removed all outside threats to Bahrain. They attacked the Wahhabis in Dammam. They also used diplomacy to stop Persian and Ottoman claims.

Inside Challenges

The Al Khalifa family treated Bahrain like their personal property. They collected as much money as possible from the local people, especially the Shia community. The Al Khalifa family took over land and property. They also destroyed local sources of power until the early 1930s. The Shia, who say they are the original people of Bahrain, talk about a perfect past. They say that before the Al Khalifa invasion, Shia religious leaders would elect a council of three. It is hard to prove or disprove this, as there are not enough old documents.

After outside threats decreased in 1828, the Al Khalifa family started fighting among themselves. These internal conflicts caused more damage to Bahrain's economy and society than outside invasions. The Shia community suffered the most. Soon after arriving in Bahrain, the Al Khalifa family split into two groups. One group was led by Salman bin Ahmed, based on the mainland. The other was led by his brother Abdulla, based on Muharraq Island. Over time, Muharraq became almost independent, with its own tribal government. Khalifa bin Salman took over after his father in 1826. Khalifa's death in 1834 made the internal conflict worse. His uncle, Abdulla, became the sole ruler of Bahrain.

Abdulla's rule (1834–1843) was full of conflicts and wars. This caused a lot of chaos in Bahrain. Its trade dropped by half. Many locals, especially the Shia, were forced to move to other ports. This was because of the harsh taxes and looting they faced. In 1835, Abdulla crushed an uprising in Qatar. This uprising was led by one of his sons and supported by other tribes. In 1842, he fought with his grandnephew, Muhammad bin Khalifa. Muhammad fled to Riyad after being defeated. Muhammad, now supported by the Wahhabis, moved to Al Zubara. There, he allied with other tribes. With his brother Ali in Manama, they defeated Abdulla. Abdulla then fled to Dammam. Between 1844 and 1846, Abdulla tried three times to get his throne back from different places. He finally left for Muscat, where he died in 1849.

In 1867, an uprising happened in Wakra and Doha in Qatar. Muhammad, wanting to buy time, invited Jassim Al Thani of Doha to Bahrain for talks. But he arrested him when he arrived. In October of that year, he declared war on Qatar. The British saw this as breaking the peace treaty. They sent their troops to Bahrain. Muhammad fled to Qatar. He left his brother Ali as ruler of Bahrain. Ali then agreed to British demands. He gave up their war ships and paid a fine of $100,000. Also, the Al Khalifa family had to give up their claims over Qatar. Britain recognized Qatar as a separate country. Muhammad returned to Bahrain after his brother convinced the British to let him in. However, they soon sent him away to Kuwait. They accused him of planning conspiracies.

Muhammad went to Qatif. With help from others, they managed to make Muhammad bin Abdulla the ruler. This happened after Ali bin Khalifa was killed in battle. Two months later, in November 1869, the British navy stepped in. Under Colonel Lewis Pelly, they took control of the island. The main leaders, except for one, were sent away to Mumbai. The British then talked with the Al Khalifa chiefs. They appointed 21-year-old Isa bin Ali as the ruler of Bahrain. He held this position until 1923. From this point until independence, Britain completely controlled Bahrain's security and foreign relations.

Economy and Government Under Isa bin Ali (1869–1923)

How money and power were managed was handled by tribal councils. These councils did not follow set laws or procedures. Personal and social matters were handled by religious courts. Each council's power came from the money and resources it controlled. During this time, Bahrain's economy relied on pearl diving, fishing, and growing palms. These ways of life existed long before Isa bin Ali's rule, but they were very important during his time.

World War I changed many things in Bahrain. It affected politics, society, the economy, and trade networks.

Ruler's Power

The ruler had a special council called diwan. Unlike other tribal councils, the ruler used force to collect taxes or anything else from people. The ruler was like the "government" without offices. He was the "administration" without a system of workers. He was the "state" without public agreement or fair laws. The ruler's power was similar to other sheikhs (members of the Al Khalifa family) who controlled their own areas. But he had more resources and wealth. The ruler controlled all ports and markets. He also controlled many areas, including Manama and Muharraq, the two largest cities. The government in Manama and Muharraq was led by a high-ranking fidawi called an emir. This group had thirty other fidawis. In Riffa, where Sunni Arab tribes lived, the emir was an Al Khalifa family member.

There was no difference between the ruler's private money and public money. All public money, including taxes and rents, was seen as the ruler's personal income. Much of this money was spent on the ruler's helpers. Very little, if any, was spent on things like schools and roads. When it was spent on these things, it was seen as a personal act of kindness. Distant relatives of the ruler were put in charge of his lands. His brothers and sons were given their own lands to prevent family conflicts. Government jobs were only for Sunnis. Market jobs were mostly for Shia and foreigners. The ruler and most sheikhs lived in Muharraq city. None lived in the Shia villages. Their fidawis and council members followed them wherever they lived.

Fidawis were the ruler's military force. Their main job was to carry out the sheikhs' orders using physical force. They were made up of people from Baluchis, African slaves, and Sunni Arabs whose tribal origins were unknown. They carried sticks and could question, arrest, and punish those they thought were wrongdoers. Bahrainis often complained about the fidawis' unfair way of handling law and order. Fidawis were also responsible for forcing people into labor, called sukhra. They would gather a random group of adult men from public places like the market. Then they would force them to do a specific task. The men would not be freed until they finished the task. These tasks usually did not need special skills and could be done in no more than two days (for example, construction).

Palm Farming and Land Management

Most farming in Bahrain was focused on palm trees. Vegetables and animal feed were only grown in small amounts. Palm trees were mainly found on the northern shores, which had the best farming land. Unlike people in central Arabia who relied on camels, Bahrainis relied on palms. Dates were a basic part of their diet. Palm branches were used to build houses and fish traps. Flowers and buds were used for medicine, and leaves for making baskets. Local culture was also deeply connected to palms. Many stories, songs, and even ways of describing people were about them. Growing palms required full-day work throughout the year. Most farmers were Shia. They involved all family members, children and adults, male and female, in the work. It was their only way to make a living.

Palm farming was tightly controlled by the ruling family. They were also the landlords. They rented out lands they directly managed. They also collected taxes on private lands. If people failed to pay, their property was taken. Only Shia people had to pay taxes. This was because they were not part of the army, even though they were never asked to join it. Land was divided into several areas. These areas were managed by sheikhs, mostly the ruler's brothers and sons. The size of each area was not fixed. It grew or shrank based on the owner's power and influence. The closer someone was to the ruler's direct family line, the more power they had and the larger their land. For example, when a ruler died, land management would shift from his brothers and sons to the new ruler's brothers and sons. The new ruler's cousins would not inherit their fathers' lands. Mothers also played an important role, especially if they were from the ruling family.

Sheikhs who controlled an area had a lot of freedom within it. Their power was almost as great as the ruler's. They imposed taxes, settled disagreements, and protected their people from outsiders, including other Al Khalifa family members. They did not deal directly with farmers. Instead, they had a wazir who would rent palm gardens through middlemen, and then to individual farmers. A wazir, which means minister in Arabic, was a Shia person trusted by the sheikh. Sometimes wazirs also acted as special advisors to the sheikh.

Besides wazirs, the sheikhs' administration included kikhda and fidawis. Kikhda were Shia people assigned to collect taxes. Because of their job, wazirs and kikhda, who lived in Shia villages, had important positions in society. But in heavily taxed villages like Bani Jamra and Diraz, they were so disliked that they fled to Manama after the reforms of the 1920s. In total, there were two to five people between the sheikh and the farmer. Contracts were spoken agreements before the reforms of the 1920s. After that, they were written down. Rents depended on how much was harvested. They increased or decreased with the yield. This meant farmers were always left with only enough to survive.

Fishing

Bahrain's waters are full of many kinds of fish. Fish had no trade value (they were not imported or exported). So, fishing traps, the main way of fishing, were not controlled by the Al Khalifa family. Most Bahrainis had something to do with fishing and the sea. They knew as much about it as people in northern Arabia knew about camels and the desert. Specialized fishermen called rassamin built fishing traps. They rented them for $150 to $5000 a year. The most expensive ones were in Sitra island. The ruling family owned a small number of fishing traps, while the Shia community owned most of them.

Pearl Diving

Pearl diving has been known in the region for thousands of years. But it became very important economically from the 1700s to the early 1900s. In 1876, pearl diving in Bahrain brought in about £180,000 each year. By 1900, this rose to £1,000,000. This was more than half the value of all exports. However, by 1925, it only brought in about £14,500. Pearls were sent to Mumbai and then to the rest of the world. Indian merchants, known as Banyans, were active in sending pearls from Bahrain to Mumbai. By the end of the 1800s, Bahraini and European merchants took over. They sent pearls directly to Europe.

In the 1800s and early 1900s, pearl diving became very important for thousands of Bahrainis. Almost half of all adult men worked in pearl diving. The official pearl diving season, called al-ghaws, lasted from May to October. Over time, a few rich merchants, known as "kings of pearl," came to control the pearl industry. This was because boat supplies were expensive, and good divers needed a lot of money to hire.

A boat's crew had six types of workers: the pilot (nukhada), his assistant, divers, pullers, apprentices, and servants. While at sea, the pilot, who was usually from a tribe and owned the boat, had the power to judge and punish wrongdoers. He also settled disagreements. Unless crimes were too serious for him to handle, they were dealt with using "an eye for an eye." Otherwise, they were dealt with after returning to land. The rest of the crew were from southern Persia, Baluchis, or slaves. Only a few were native Shia. Divers and pullers worked as a team. Divers stayed at the bottom of the sea collecting pearl oysters until they needed to breathe. Then they would pull a rope attached to them. More pullers would then pull them back to the boat. Good divers could stay underwater longer and make 100 dives a day. They had more respect than pullers. But they also faced dangers like eardrum rupture and blindness.

Even though pearl diving made a lot of money, divers and pullers got only a small share. Pilots and merchants got most of it. Disagreements over shares and loans were usually taken to Islamic courts. But if it was about pearls, it went to a special court called the salifa. This court was unfair to merchants and pilots because its judge was always from a tribe. In a system similar to palm farming, interest on loans increased with the pearl catch. So, divers and pullers were almost always in debt to the pilot. The pilot, in turn, was in debt to the merchant. Skilled divers were given bigger loans. This meant they were more in debt. They had to keep working with the same pilot because they could not pay the loan and its high interest (up to 50 percent) on their own. Loans were also passed down from fathers to sons. They could take another loan from a different pilot to pay the first, but they would still be stuck in the system. Only a few divers were rewarded for their loyalty and hard work.

Pearl diving was controlled by Sunni Arab tribesmen. They had a lot of freedom within their areas. They settled disagreements and held their own courts. But they did not collect taxes. Each tribe controlled specific pearl banks. The power of each tribe came from their overall power in the Gulf and Arabia. The most powerful tribe was Al Dawasir. They lived in Budaiya and Zallaq. They were rich, numerous, and could gather many allies in Arabia. To attract as many pearl tribes as possible, the Al Khalifa family did not interfere with pearl diving. They also did not tax boats or catches. This increased the amount of exports and thus increased taxes on them. It also increased local trade and rents. Interfering in tribal affairs had bad results. Tribes threatened to move away, which would mean less trade and a hidden threat of war. This happened with the Al Bin Ali tribe in 1895 and the Al Dawasir tribe in 1923. Both moved away from the island.

Some historians argue that the Al Khalifa family's tight control over palm farming and relaxed rules for pearl diving was not meant to favor Sunnis and oppress Shia. Instead, their goal was to make as much money as possible from both groups. Sunni tribes strongly resisted any interference in their affairs. They also had better production in a relaxed environment.

Religious Courts

Religious courts at the time followed Sharia (Islamic law). This law comes from the Qur'an and Hadith. There were four different religious groups in Bahrain then. Urban Hawala (Sunni) followed Shafi'i law. Urban Najdi (Sunni) followed Hanbali law. Tribal Arab Sunni communities followed Maliki law. The Shia community followed Ja'fari jurisprudence. During Isa bin Ali's entire rule, Jassim al-Mihza was the only religious judge for the Sunni community. Appointed by the ruler, al-Mihza handled personal and family matters like divorce and inheritance. But loans related to pearl diving were not included. This was because Sharia clearly speaks against loan interests. Instead, these loans were taken to the tribal salifa court.

The Shia courts, on the other hand, were many and independent of the ruler. Their judges were not appointed or inherited their positions. They gained their positions through their wisdom and qualities. They used ijtihad (interpretation) instead of qiyas (analogy). Shia judges had more social power than their Sunni counterparts. This was because they were independent of the government. Also, religion had more social influence on Shia people, as they believed in taqlid, which means religious imitation. In addition, Shia judges controlled how money from Shia religious properties was used. These properties included land, fish traps, houses, shrines, and more. The Shia religious properties were much more numerous than the Sunni ones. They were run in a similar way to tribal councils, but they followed Islamic principles. So, Shia judges offered an alternative to the government. Their followers saw them as the "legitimate" authority. The ruler, however, treated them as religious leaders.

British Protectorate

The British signed two more treaties with the Al Khalifa family in 1880 and 1892. These treaties gave Britain control over Bahrain's defense and foreign relations. This made Bahrain a British colonial protectorate. After an event in 1904, where a relative of the ruler attacked Persians and Germans, the ruler agreed to let Britain handle foreign affairs. The term "foreigner" was unclear. Bahrain had no laws for becoming a citizen, no population count, or an office for people leaving the country. This, along with the fast-growing number of foreigners due to the pearl boom, created two systems of power. One was led by the British agent, and the other by the Al Khalifa ruler (Isa bin Ali).

During the First World War, Bahrain was again threatened by the Wahhabis. They had re-occupied the eastern part of Arabia. The Ottomans and Persians also did not give up their claims over the island. Britain responded by tightening its control over Bahrain. Bahrainis were not supportive of the Allies. The British thought this was because they had not paid enough attention to the Shia community's problems and had not enforced reforms. When the war ended, Britain changed its policy in Bahrain. Instead of being careful and giving advice to the ruler, they started directly making reforms.

Government Reforms

The government reforms happened between 1919 and 1927. These changes, sometimes called "reforms of the twenties," were about how the government was run. They were not about who should rule or giving people a say in government. Instead, they focused on changing public offices and economic resources. These reforms were not just because Britain stepped in. Other things, like Bahrain's social order and tribal system, also played a big part. The main result of these reforms was the creation of a modern government system.

Starting in 1919, H. R. P. Dickson, the British political agent, began improving schools, courts, local governments, and other institutions. In 1919, a joint court was set up. It was led by Dickson and Abdulla bin Isa, the ruler's son. This court handled cases involving foreigners against Bahrainis. The next year, the fidawis (the ruler's armed group) were removed after a Municipal Council was formed. All council members were appointed. Half were chosen by the ruler and half by the British. Their job was to handle civil responsibilities. In 1923, the salifa court (for pearl diving disputes) was removed. It was replaced by the Customary Council. This council was formed in 1920. Its members were appointed in the same way as the Municipal Council. But it was given power over trade, including the pearl industry. In the same year, a Shia religious judge was appointed to the government. The Al Khalifa family and their allies rejected these reforms. They sent many requests to the Mumbai government against Dickson's changes.

Challenges to Reforms

Dickson was replaced by Major C. K. Daly (1920–1926). Unlike Dickson, Daly used strong and firm methods to introduce reforms. He started by reducing the power of Abdulla bin Isa, who strongly opposed the reforms. He also strengthened Abdulla's elder brother and the next in line to rule, Hamad bin Isa. By 1921, the country was split into two groups. One group supported the reforms. This group included Hamad bin Isa, the British political agent, and the Shia community (who made up about half the population). The other group opposed the reforms. This group included the ruler, his son Abdulla, and tribal members. Both groups sent many requests to different British officials, including the Foreign Office.

The Shia community desperately wanted to get rid of the tribal system. In one of their many requests to Daly, they asked for Bahrain to be officially protected by Britain. Daly supported their demands. He wrote a letter to a higher official. In it, he mentioned the Al Khalifa family's poor management and corruption. He also spoke of the "harsh actions and unfair treatment" they had done, especially by Abdulla bin Isa. The other group, mainly the tribal chiefs and pearl merchants, rejected the reforms. They argued that fair and standardized laws would take away their advantages. These advantages included not paying taxes and having power over their lands. The Bombay government was careful and moved slowly. The year 1922 ended without the reform plans being put into action. This encouraged the Al Khalifa family and the Al Dawasir tribe, who felt they would lose the most, to use violence. The Al Dawasir tribe asked for help from the Wahhabis. The Wahhabis controlled Al-Hasa and wanted to add Bahrain to their new religious state.

Full-scale violence broke out in 1923, after smaller incidents the year before. The violence stopped after the British fleet arrived in Bahrain. After that, ruler Isa bin Ali was forced to step down. His son, Hamad, took over. However, the requests and political crisis continued into Hamad's rule.

Hamad began his rule (1923–1942) by setting up a criminal court. This court was to try those involved in the violence.

Putting Reforms into Action

One of the ruler's cousins tried to assassinate him in 1926, but it failed. Other than that, the rest of his rule was peaceful. He continued to put the government reforms into action. In 1926, a new "adviser" position was created. This person would handle Bahrain's internal affairs. From its creation until 1957, this position was held by Charles Belgrave. He became known locally as "the adviser."

- Pearl Industry

The reforms in the pearl industry happened between 1921 and 1923. These were a "test" for the whole reform process. They faced the strongest resistance from the tribes. Once this tribal resistance was broken, the way was open for other reforms. These reforms focused on protecting divers' interests. They also aimed to limit the merchants' control over the pearl industry. The changes included separating business activities from pearl diving. Pilots also had to write down a record for every diver in a book held by the diver. In the 1930s, the pearl industry lost its importance. This was due to several reasons, including the creation of cultured pearls and the discovery of oil.

- Private Property and Public Rights

Starting in the early 1920s, a long and detailed land survey was done. An Indian team registered private properties. Those who had lived on a piece of land for ten years or more, or had "gift declarations" from the ruler, were given ownership of the land. Soon, problems arose within the ruling family over how to divide former lands. But a deal was reached in 1932. This deal included ending forced labor and tax collection. It also set up a "family court" to handle disagreements within the Al Khalifa family. In total, the ruling family owned 23% of the palm gardens. This made them the second-largest landowners after private landowners.

Land renting was put under government control. Parties involved had to write down and submit the terms of their contracts to the authorities. With taxes and forced labor ended, wazirs and kikhdas were no longer needed. So, these positions were removed. A lighter state tax system was introduced. It only contributed a small part to the state budget. The biggest part came from customs, especially those on the pearl industry. The ruling family received much of the budget. In 1930, half of it was given to them as allowances or salaries.

- Justice System

There was no standard set of laws. So, the Joint Court, set up in 1919, used Indian, British, or Sudanese laws as needed, along with local customs. Before the Bahrain Court was established in 1926, cases went to the Joint Court, Sharia courts, or the Customary Council. The Bahrain Court was both the lowest and highest court until a Bahrain Lower Court was set up in 1927 and an appeal court in 1939. It was led by the adviser and a member of the Al Khalifa family. Religious courts became part of a central justice system. But they were under the Bahrain Court. This weakened the power of Shia religious judges.

- Policing System

The fidawis were replaced by municipal police in 1920. In 1922, most police officers were Persians. But in 1924, one hundred Baluchis were hired. The Baluchis were later removed after several problems with their skills and behavior. They were replaced by retired Indian Army Punjabis. These Punjabis served until 1932. The policy of hiring from "minority cultures" continued. Because of this, Bahrainis avoided joining the police. By the 1960s, Bahrainis made up only 20% of the police. The rest were foreigners (Baluchis, Yemenis, Omanis, etc.). The Bahrain army was founded in 1968. It adopted the style of the Jordanian army. Bahrainis, especially those from tribal origins (Sunnis), made up most of its recruits. Villagers (Shia) made up only a small percentage in non-fighting departments. In general, Sunnis from tribal origins controlled important departments like justice, interior, military, and immigration. The Shia community mostly worked in technical departments like water, health, finance, and electricity.

- Education

The first school in Bahrain was the American Missionary School (now Al Raja School). It was built in the early 1800s. At first, it only attracted Christians and Jews. Bahrainis only started sending their children there in the 1940s and 1950s. The first two Arabic schools in Bahrain were separated by religious groups. Al-Hidaya, built in 1919 in Muharraq, was for Sunnis. Al-Ja'fariyah, built in 1929 in Manama, was for Shia. The Al Khalifa family saw this religious division as a threat to their power. So, in 1932-1933, both schools were opened to everyone. Their names were changed to Muharraq and Manama primary schools. In the following years, more public schools were opened, and an education department was founded.

Discovery of Oil

A study of the land in the Persian Gulf region was done in 1912. This is believed to be the first such study in the area. In 1914, Bahrain's ruler promised Britain that he would not allow oil to be taken or give any oil rights without their approval. The first oil rights were given to the Bahrain Petroleum Company in 1928. Oil was later found in Bahrain in 1931. The first oil shipment was sent out a year later. A few years later, an oil refinery was built in Sitra. It processed and refined Bahrain's 80,000 barrels of oil each day. It also processed 120,000 barrels from Dammam in nearby Saudi Arabia, which was connected by a pipeline. In the following decades, money from oil increased a lot. It went from $16,750 in 1934 to $6.25 million in 1954, and to $225 million in 1974. The discovery and production of oil brought many economic and social changes to the island.

Economically, pearl diving and palm farming, which were once the main parts of Bahrain's economy, almost disappeared. The number of pearling boats dropped from 2,000 in the 1930s to 192 in 1945, and to none by the 1960s. Oil production offered steady jobs, not just in Bahrain, but across the whole Persian Gulf region. Many Bahrainis moved to other places for these jobs. This, along with pearl tribes moving away, reduced the number of divers. This led to the end of pearl diving. Palm farming declined for similar reasons, but it was more gradual. It dropped sharply only in the 1960s and later. Instead of farming palms, growing vegetables became more common. Palm farming became a luxury activity.

See also

- Bahrain province