A History of British Birds (Yarrell book) facts for kids

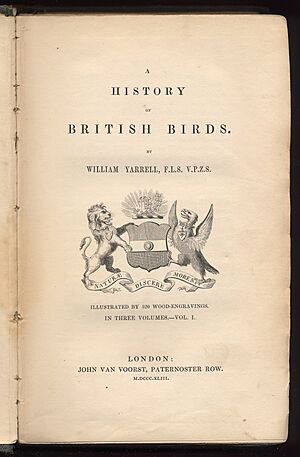

Title-page of first edition

|

|

| Author | William Yarrell |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Alexander Fussell (drawing) John Thompson (engraving) |

| Country | England |

| Subject | Birds |

| Genre | Natural history |

| Publisher | John Van Voorst, Paternoster Row, London |

|

Publication date

|

1843 |

| Pages | 3 vols (525, 669, 528 pp.) |

A History of British Birds by William Yarrell is a famous book about birds found in Britain. It was first fully published in three books in 1843. Before that, it came out in smaller parts over six years.

This book isn't about the history of bird science. Instead, it's a guide that describes every bird species known in Britain at the time. Each bird gets its own section, usually about six pages long. These sections include a picture, a description, and details about where the bird lives around the world. They also share interesting stories about the birds' behavior.

Yarrell's book quickly became the main guide for bird experts in Britain. It was more scientifically correct than older books, like one by Thomas Bewick with the same name. But like Bewick's book, it mixed scientific facts with accurate pictures, detailed descriptions, and fun stories. This made it popular with both scientists and the general public.

William Yarrell was a newsagent, not a university-trained scientist. He talked with many famous naturalists, like Thomas Pennant and Coenraad Jacob Temminck. He also read works by scientists like Carl Linnaeus. This helped him gather correct information for the hundreds of birds in his book.

The book has over 500 drawings. Most were drawn by Alexander Fussell directly onto wood blocks. Then, John Thompson carved these drawings into the wood. The book was first released in 37 parts. Later, these parts were collected and bound into books. Four different versions of the book were made between 1843 and 1885.

Contents

About the Author: William Yarrell

William Yarrell (1784–1856) was born to Francis and Sarah Yarrell. His father and cousin owned a book and newsagent business in London. William joined the family business in 1803 after finishing school. He took over the company in 1850.

Yarrell had enough free time and money to enjoy his hobbies. He loved shooting and fishing. He soon became interested in rare birds. He even sent some bird samples to the famous artist and writer Thomas Bewick.

He became a very keen student of natural history. He collected birds, fish, and other wildlife. By 1825, he had a large collection. He was also active in many science groups in London. He held important roles in several of them for many years. For example, he was the treasurer of the Linnean Society of London and a vice president of the Zoological Society of London.

Knowing many leading naturalists of his time helped him a lot. This was especially true when he wrote his books. His most famous works are A History of British Fishes (1836) and A History of British Birds.

How the Book Was Made

Yarrell knew about earlier bird guides, especially Bewick's popular book. Yarrell even used the same title, A History of British Birds. But Yarrell's book was different. He used a lot more communication with other experts. He also focused more on scientific accuracy. This was possible because bird knowledge was growing fast in the 1800s.

Talking to Experts and Collecting Samples

Yarrell wrote many letters to people all over Britain and Europe. He also looked at other bird guides. He used his memberships in groups like the Zoological Society of London to learn about new discoveries. He referred to the work of many bird experts, including William Macgillivray, John James Audubon, and John Gould.

During the six years he was writing the book, many people sent him descriptions, observations, and bird samples. These contributions filled the book with new information. Yarrell wrote in his introduction that he learned about "many occurrences of rare birds" from friends and other publications.

Sometimes, Yarrell's friends and books helped him describe where a bird lived around the world. For example, for the ringed plover, he used information from experts in Sweden, Norway, Lapland, Russia, Siberia, Turkey, and Japan. For the wood sandpiper, he got samples from Malta and South Africa. Yarrell also wrote about his own observations. For instance, he mentioned finding young wood sandpipers and one nest with eggs.

How the Book is Organized

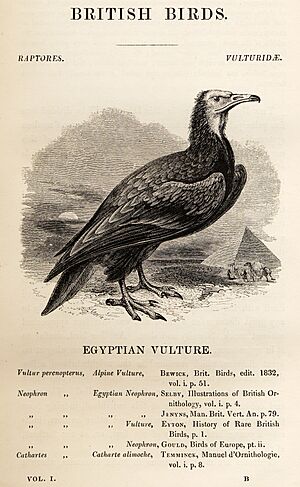

Yarrell followed Bewick's style by giving each bird its own section. There isn't a main introduction or a table of contents. The first bird, the Egyptian vulture, starts right after the index.

Like Bewick, each section begins with a large wood carving of the bird. The pictures show the bird in a natural setting. For example, the Egyptian vulture picture shows a pyramid and camels. A key difference from Bewick is that Yarrell immediately lists the bird's Latin names. This shows his more scientific approach and how much bird science was changing.

For the first bird in each group, like the vulture group Neophron, Yarrell adds a "Generic Characters" paragraph. This describes the beak, legs, wings, and other features that help identify the bird. These details often required looking closely at bird samples. The book often mentions that people shot birds to collect unusual ones. The Egyptian vulture, for example, was described from a bird shot in Somerset, England. Yarrell then describes where the bird lives, what it does, what it eats, and how it looks. A typical bird section, like the Egyptian vulture's, is about six pages long.

Many articles end with a small carving called a "tail-piece." Yarrell's tail-pieces are more serious than Bewick's. They often give more information. For example, the Egyptian vulture article ends with a detailed carving of another vulture. This shows both young and old birds with different feathers, which are also described in the text.

Bird Descriptions and Stories

Besides simple facts, Yarrell added many stories to make the bird descriptions more lively. He chose these stories from his own experiences, from his friends, or from recently published accounts.

For example, for the "Fulmar Petrel," he quotes a long article by John Macgillivray. This article describes a visit to St Kilda in 1840. It explains how many fulmars live there and how important they are to the islanders. It also talks about how the birds vomit oil, which smells bad but is very valuable.

Yarrell was realistic about hunting, just like Bewick. He notes that corncrakes "are considered most delicate as articles of food." But he always provides accurate and entertaining stories. For instance, he tells a story about a corncrake that pretended to be dead when caught by a dog. It fooled a gentleman twice before finally escaping!

Yarrell's Own Discoveries

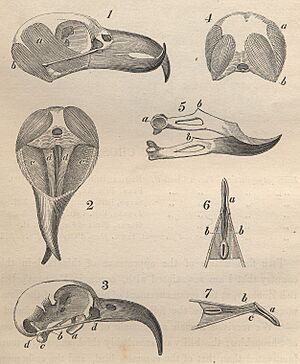

Yarrell didn't just collect information. He also made his own scientific observations. He described the windpipe (trachea) of several bird species. He also wrote a detailed, seven-page account of the skull, jaw, muscles, and feeding of the common crossbill (Loxia curvirostra). The crossbill article is one of the longest in the book, at 20 pages.

Yarrell was very interested in the crossbill's head. He wrote that its unique beak and how it works had always fascinated him. He explained that crossbills are special because their beaks move sideways. He described the bones and muscles that allow this powerful side-to-side action.

He then quoted a Mr. Townson, who described how crossbills eat pine cones. They insert their beaks between the scales and force them sideways to open the cone. Yarrell then went back to anatomy, explaining in detail how the tongue helps get the seed out. He then shared another quote from Mr. Townson, who said crossbills loved to use their strong beaks for fun. They would even tear up pencils!

Yarrell added his own observation, correcting a famous scientist named Buffon. Buffon had said the crossbill's beak was a "defect of Nature." But Yarrell proved that crossbills could pick up tiny seeds. He concluded that the crossbill's beak, tongue, and muscles are a beautiful example of how nature adapts things perfectly for a purpose.

Amazing Illustrations

Yarrell's book used wood engravings for its pictures. This method was made popular by Bewick. It involved carving images into the end grain of boxwood blocks using a special tool called a burin.

Making illustrated books in the 1800s was expensive, especially if the pictures were hand-colored. By using black-and-white wood engravings, Yarrell saved money. This also meant the pictures could be printed directly on the same pages as the text.

Alexander Fussell drew most of the pictures for the book. Yarrell thanked Fussell for "nearly five hundred of the drawings." He also thanked John Thompson and his sons for carving these drawings into wood. The book's title page says there are 520 drawings in total.

Besides bird figures, there are 59 small "tail-pieces." These are small woodcuts that fill empty spaces at the end of articles. Some are funny, like Bewick's. But many show details of bird anatomy, like breastbones and windpipes. Others show birds' behavior or how humans interact with birds. For example, one tail-piece shows a bittern swallowing a frog. Another shows how to shoot an eagle from a pit.

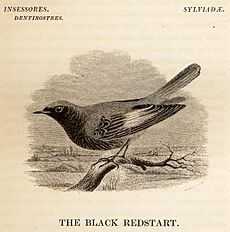

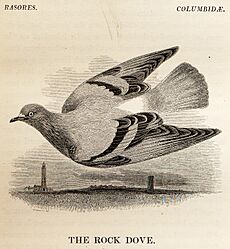

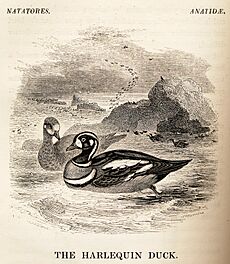

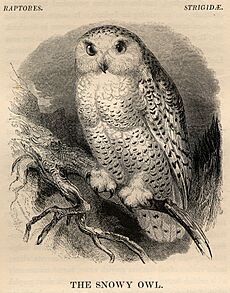

Fussell worked on the drawings for six years, starting in 1837. Many drawings were made from bird skins or stuffed specimens. But every bird picture looks alive, showing the bird standing, flying, or swimming in its natural home. Some drawings are signed "A. FUSSEL DEL." (meaning A. Fussel drew this). A few, like "The Black Redstart," are signed "THOMPSON DEL ET SC." (meaning Thompson drew and carved this).

The quality of the illustrations was very high. This was because Yarrell could afford to hire Thompson and his sons, who were very skilled. Thompson senior even won a gold medal at the 1855 Paris Exhibition.

Book Contents

The first edition of the book was organized into four main groups, called "Orders." These groups don't exactly match how birds are classified today.

Volume 1

- Introduction and Index

- Raptores (Birds of Prey, like the Egyptian vulture to Tengmalm's owl)

- Insessores (Perching Birds, like the Great grey shrike to Twite)

Volume 2

- Insessores (continued, like the Bullfinch to Nightjar)

- Rasores (Scratching Birds, like the Common wood pigeon to Little bustard)

- Grallatores (Wading Birds, like the Cream-colored courser to Purple sandpiper)

Volume 3

- Grallatores (continued, like the Collared pratincole to Red-necked phalarope)

- Natatores (Swimming Birds, like the Greylag goose to Storm petrel)

In Popular Culture

Yarrell's Birds was mentioned in a famous letter to The Times newspaper in 1913. A scientist named Richard Lydekker wrote that he had heard a cuckoo in February. This was unusual because Yarrell's book said hearing cuckoos so early should be doubted. Six days later, Lydekker wrote again, admitting that the sound was actually made by a bricklayer! Letters about the first cuckoo of the year then became a tradition in the newspaper.

Different Editions

Birds was first published in 37 parts, with three sheets each. These parts came out every two months, from July 1837 to May 1843. The sheets were then put together into three books. New information about rare birds was added to these collected volumes.

The book was printed in three different sizes. The smallest was "octavo." There were also two "large paper" sizes. A special extra section was added in 1845. Only 50 copies of the largest size edition from 1845 included this extra section.

The fourth edition of the book was updated and expanded by bird experts Alfred Newton and Howard Saunders. It included even more illustrations, bringing the total to 564 engravings.

- First edition, 1843. 3 volumes. (with an extra section in 1845).

- Second edition, 1845.

- Third edition, 1856.

- Fourth edition, 4 volumes. Published between 1871 and 1885. Volumes 1 and 2 were edited by Alfred Newton. Volumes 3 and 4 were edited by Howard Saunders.

Tail-pieces in the Book

Yarrell's tail-pieces are small engravings placed at the end of articles. They follow the style set by Thomas Bewick. However, Yarrell's tail-pieces are rarely silly or whimsical. Instead, many of them are like extra pictures. They show details of bird anatomy or features that help identify birds.

Images for kids

-

Tracheae and bronchial tubes of male and female shoveler ducks

-

Sternum and trachea of a young male crane

-

Tail-piece vignette showing "a mode of shooting an Eagle from a pit"

-

Tail-piece of bittern swallowing a frog

-

Whimsical tail-piece of mediaeval lady and gentleman on horseback with falcons

See Also