Corn crake facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Corn crake |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Gruiformes |

| Family: | Rallidae |

| Genus: | Crex Bechstein, 1803 |

| Species: |

C. crex

|

| Binomial name | |

| Crex crex (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

|

|

|

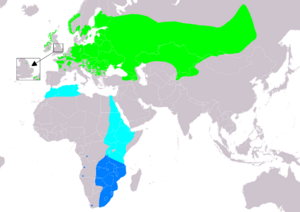

| Range of C. crex Breeding Passage Non-breeding Extant & Reintroduced (breeding) | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The corn crake, also called the corncrake or landrail (Crex crex), is a fascinating bird. It belongs to the rail family, which includes nearly 150 species. This medium-sized bird breeds in Europe and Asia, as far east as western China. When winter arrives in the Northern Hemisphere, corn crakes fly all the way to Africa.

Corn crakes have brownish-black feathers on their backs, streaked with buff or grey. Their wings have cool chestnut markings, and their undersides are blue-grey. You might notice rust-coloured and white stripes on their sides. They have a strong, flesh-coloured beak, pale brown eyes, and pale grey legs. Young corn crakes look a lot like adults. Baby chicks are black, just like all rail chicks.

The male corn crake makes a very loud krek krek call. This sound is so unique that it gave the bird its scientific name, Crex crex. Corn crakes are a bit larger than their closest relative, the African crake. African crakes are also darker and have plainer faces.

Corn crakes love to live in grasslands, especially hayfields. They build their nests on the ground, hidden in grass leaves. Females lay 6 to 14 cream-coloured eggs with reddish-brown spots. These eggs hatch in about 19 to 20 days. The black chicks are ready to fly after about five weeks. Sadly, modern farming methods often destroy nests before the chicks are ready. This has caused a big drop in corn crake numbers in many areas.

Corn crakes eat a mix of things, but mostly small creatures without backbones, like insects. They also eat some plants, seeds, and grains. Even though their numbers have gone down in western Europe, the corn crake is listed as "least concern" by the IUCN Red List. This is because there are still many of them in Russia and Kazakhstan.

Contents

Discovering the Corn Crake's Name

The rail family is a group of nearly 150 bird species. Scientists believe this family started in the Old World (Europe, Asia, Africa). The corn crake's closest relative is the African crake.

The famous scientist Carl Linnaeus first described the corn crake in 1758. He called it Rallus crex. Later, in 1803, a German scientist named Johann Matthäus Bechstein moved it to its own group, Crex. He named it Crex pratensis. But because Linnaeus used crex first, the bird's official name became Crex crex.

The name Crex crex comes from an ancient Greek word that sounds like the bird's call. It's an example of onomatopoeia, where a word sounds like what it describes. The common English name "corn crake" refers to how the bird nests in dry hay or grain fields. Most other birds in this family prefer marshes.

What Does a Corn Crake Look Like?

The corn crake is a medium-sized bird. It is about 27 to 30 centimeters (11 to 12 inches) long. Its wings can spread out from 42 to 53 centimeters (17 to 21 inches) wide. Males usually weigh about 165 grams (5.8 ounces), and females weigh around 145 grams (5.1 ounces).

Adult males have brown-black feathers on their head and back, with streaks of buff or grey. Their wing feathers are a bright chestnut colour with some white stripes. Their face, neck, and chest are blue-grey. They have a pale brown stripe from their beak to behind their eye. Their belly is white, and their sides have chestnut and white bars. The beak is flesh-coloured, the eyes are pale brown, and the legs and feet are pale grey.

Females look similar but have warmer brown colours on their backs. Their eye stripe is also narrower and duller. After the breeding season, both males and females get darker feathers. Young birds look like adults but have a yellowish tint. Baby chicks are completely black.

Corn crakes don't have different types (subspecies). However, birds from the eastern parts of their range tend to be a bit paler. Adults change all their feathers after breeding, usually by late August or early September. They do this before flying to Africa for the winter.

When in Africa, the corn crake lives in the same areas as the African crake. But you can tell them apart because the corn crake is bigger. It also has paler upper feathers and a different pattern on its underside. When flying, the corn crake has longer, less rounded wings. It also has a white edge on the inner part of its wing.

The Corn Crake's Voice

On their breeding grounds, male corn crakes make a very loud and repeated krek krek sound. They usually make this call from a low spot, with their head and neck pointing up and their beak wide open. You can hear this call from up to 1.5 kilometers (0.9 miles) away! This call helps them claim their territory, attract females, and warn other males to stay away.

Each male's call is slightly different, so you can tell them apart. Early in the season, they call almost all night and sometimes during the day. A male might repeat his call more than 20,000 times in one night! This loud call helps females find them, even though the birds are hidden in tall plants.

Female corn crakes can make a call similar to the male's. They also have a unique barking sound. Chicks make a quiet peeick-peeick sound to stay in touch. They also chirp when they want food. Because corn crakes are so hard to see, scientists often count them by listening for the males calling at night.

Where Corn Crakes Live and Travel

Corn crakes breed from Ireland all the way east through Europe to central Siberia. They used to live in many more places, but their numbers have dropped. There's also a large group of them in western China.

For winter, corn crakes fly mainly to Africa. They spend their winters from the Democratic Republic of the Congo south to eastern South Africa. They are mostly seen during migration in other parts of Africa.

These birds migrate along two main routes: one through Morocco and Algeria, and another, more important one, through Egypt. They have been seen in many countries between their breeding and wintering areas. Some birds from Scotland even stopped in West Africa on their way south.

The corn crake usually lives in lowlands. But they can breed at high altitudes too, up to 1,400 meters (4,600 feet) in the Alps. Their natural homes used to be grassy river meadows. Now, they mostly live in cool, moist grasslands used for hay. They like traditional farms where grass is cut less often. They avoid very wet places and open areas.

After breeding, adults move to taller plants like reeds or nettles to change their feathers. In Africa, they live in dry grasslands and savannas. They like plants that are 30 to 200 centimeters (1 to 6.5 feet) tall. They can also be found in old fields or uncut grass.

How Corn Crakes Behave

The corn crake is a very shy bird. It usually stays hidden in tall plants. But sometimes, they can become quite friendly! There's a story of a corn crake in Scotland that came into a kitchen for five summers to eat food scraps.

In Africa, they are even more secretive. They are rarely seen out in the open. Corn crakes are most active early in the morning and late in the evening. They also like to be active after heavy rain or during light rain. Their flight looks weak and fluttering, but they can fly long distances for migration. When they walk, they lift their legs high. They can run very fast through grass, keeping their body flat. They can even swim if they need to.

If a dog scares a corn crake, it will fly less than 50 meters (160 feet). It often lands behind a bush and then crouches down. If it's in the open, it might run a short distance with its neck stretched forward. Then it stands up straight to watch what scared it. If caught, it might pretend to be dead!

Corn crakes are usually alone in their winter homes. Each bird uses a small area of about 4 to 5 hectares (10 to 12 acres). But they might move around if there's flooding or if the grass is cut. During migration, groups of up to 40 birds might form. They sometimes travel with common quails. They migrate at night.

Breeding Habits

Scientists used to think that corn crakes only had one mate. But it turns out that a male corn crake might have a shifting territory. He can mate with two or more females, moving on when the eggs are almost laid. A male's territory can be anywhere from 3 to 51 hectares (7 to 126 acres). Females have much smaller territories, about 5.5 hectares (14 acres).

When another male enters his territory, the male will call with his wings down and head forward. If the intruder doesn't leave, they might face each other with raised heads and wings touching the ground. They run around, making growling sounds and lunging at each other. Sometimes, they even fight, jumping and pecking. Females do not help defend the territory.

The male might offer food to the female during courtship. He also does a short dance where he stretches his neck, holds his head down, fans his tail, and spreads his wings. The nest is usually in grassland, hidden in a hollow on the ground. It's made of dry grass and other plants, lined with finer grasses.

A female corn crake lays 6 to 14 eggs, but usually 8 to 12. The eggs are oval, slightly shiny, and creamy with reddish-brown spots. They are laid one egg per day. Only the female sits on the eggs. She sits very still when disturbed, which can be dangerous during hay-cutting. The eggs hatch together after 19 to 20 days. The chicks leave the nest within a day or two. The female feeds them for a few days, but then they find their own food. Young birds can fly after 34 to 38 days.

Nests in quiet places are very successful, with 80-90% of chicks surviving. But in fields that are fertilized or used for crops, success is much lower. The way and time of mowing grass is very important. Machines can kill many chicks. Adults can often escape, but some females sitting on nests die.

What Do Corn Crakes Eat?

Corn crakes eat both plants and animals, but mostly small creatures without backbones. This includes earthworms, slugs, snails, spiders, beetles, dragonflies, and grasshoppers. They also eat small frogs and mammals sometimes. For plants, they eat grass seeds and cereal grains. In Africa, their diet is similar, but they also eat termites and cockroaches.

They find food on the ground, on low plants, and inside clumps of grass. They might search through fallen leaves with their beak. They also run to catch active prey. They usually hunt while hidden, but sometimes they feed on grassy tracks or dirt roads. They swallow small stones, called grit, to help grind up food in their stomach.

Who Hunts the Corn Crake?

Animals that hunt corn crakes include wild and pet cats, American mink, ferrets, weasels, rats, otters, and red foxes. Birds like the common buzzard and hooded crow also hunt them. In Lithuania, raccoon dogs have been known to catch corn crakes.

When chicks are exposed by fast mowing, large birds like the white stork, harriers, other birds of prey, gulls, and crows might catch them. Nests in quiet places are rarely attacked.

Corn crakes can also get sick from tiny worms and other parasites. Sometimes, bacteria can cause illness in these birds.

Corn Crake Conservation Status

The corn crake is currently listed as "least concern" on the IUCN Red List. This is because there are still many of them, especially in Russia and Kazakhstan. There are an estimated 1.3 to 2.0 million breeding pairs in Europe. Most of these are in European Russia.

However, in western Europe, the number of corn crakes has dropped a lot. This decline started in the 1800s and sped up after World War II. The biggest reason for this is that nests and chicks are destroyed by early mowing. Farmers now cut hay earlier and faster because of modern machines and fertilizers. Old-fashioned hand-cutting with scythes was much slower.

Modern machines can cut large areas quickly. This leaves the corn crake with no safe places to raise their chicks. The way machines cut, often from the outside of a field inwards, traps the chicks. This gives them little chance to escape. Adults can often fly away, but some females sitting on nests die.

Loss of habitat is another big threat. Traditional hay meadows are being replaced by different types of farmland. In eastern Europe, the end of collective farming has led to many fields being left unmanaged. Other local threats include spring floods and disturbance from roads or wind farms.

Corn crakes are also sometimes hunted. In Egypt, many migrating birds are caught in nets set for quail. This can affect a large number of birds.

Many European countries are working to protect the corn crake. They are trying to change when and how hay is harvested. Cutting later gives the birds more time to breed. Leaving uncut strips at the edges of fields and cutting from the center outwards helps chicks escape. If these changes are made widely, they could stop the population decline. Stopping illegal hunting is also important. Some countries are even trying to bring corn crakes back to areas where they disappeared.

Corn Crakes in Culture

Most rails are shy wetland birds that people don't notice much. But the corn crake used to be a common farm bird with a loud call at night. This call sometimes kept people awake! Because of this, the corn crake has many local names and appears in old stories and poems.

Names for the Corn Crake

The name for this bird has changed over time. "Landrail" and different spellings of "corncrake" have been popular. The name "corncrake" became well-known because of Thomas Bewick's book A History of British Birds in 1797.

Other names, like "quailzie" or "king of the quail," show that people linked the corn crake to the small gamebird, the quail. The name "daker" might come from the sound the bird makes, or from an old Norse word meaning "cock of the field."

Corn Crakes in Literature

The corn crake appears in poems by famous writers. The 17th-century poet Andrew Marvell wrote about a mower accidentally cutting a corn crake in his poem "Upon Appleton House". He wrote about how dangerous it is for birds to nest low in the grass.

John Clare, an English poet from the 1800s, wrote "The Landrail." This poem is about how hard it is to see corn crakes, even though you can hear them. He wrote, "Tis like a fancy everywhere / A sort of living doubt." His writings help us understand where corn crakes lived when they were more common.

The Finnish poet Eino Leino also mentioned the bird in his poem "Nocturne":

The corncrake's song rings in my ears,

above the rye a full moon sails

People sometimes use the corn crake's call to describe someone with a harsh or unpleasant voice. This saying has been around since the 1800s.

Corn Crakes in Music

In the song "Lullaby of London" by The Pogues, Shane MacGowan uses the corn crake's cry. He sings about how he misses the countryside in the city:

Though there is no lonesome corncrake's cry

Or sorrow and delight

You can hear the cars

And the shouts from bars

And the laughter and the fights

In The Decemberists song "The Hazards of Love 2 (Wager All)", Colin Meloy sings: "And we'll lie until the corn crake crows."

Images for kids

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |