History of Chester facts for kids

The history of Chester goes back almost 2,000 years! The city of Chester was first built as a strong fort called Deva Victrix by the Romans around AD 70. This was a very important place for battles between the Welsh and Saxon kingdoms after the Romans left. Later, the Saxons made the fort even stronger to protect it from Viking raiders.

After the Norman Conquest in 1066, Chester became very important. It was ruled by the Earl of Chester and was a key place for defending against Welsh attacks. It was also a starting point for trips to Ireland.

Chester grew into a busy trading port. But over time, the Port of Liverpool became more powerful. Even so, Chester didn't fade away. During the Georgian and Victorian times, people saw it as a nice escape from the busy, industrial cities like Manchester and Liverpool.

Contents

Roman Chester: A Mighty Fort

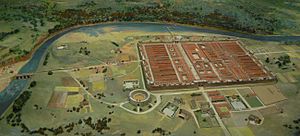

The Romans built Chester as a fortress called Deva Victrix in the AD 70s. It was in the land of the Celtic people called the Cornovii. They built it during their expansion north into Britain.

The name "Deva" might have come from the goddess of the River Dee, or directly from the British name for the river. The "Victrix" part came from the name of the Roman army unit, the Legio XX Valeria Victrix, who were based there. A town grew around the fort, probably started by traders and their families.

This Roman fort was 20% bigger than other forts built around the same time in Britain, like those in York and Caerleon. Some people think this means it was meant to become the capital of Roman Britain, instead of London.

Chester also had a large amphitheater built in the 1st century. It could hold between 8,000 and 10,000 people! This was the biggest military amphitheater known in Britain. The Minerva Shrine in the Roman quarry is the only Roman shrine carved into rock that is still in its original place in Britain.

The Roman army stayed at the fort until at least the late 4th century. Even after the Romans left Britain around 410, people continued to live in the town. They probably used the fort's strong walls to protect themselves from raiders coming from the Irish Sea.

After the Romans: Saxons and Vikings

By 410, the Romans had mostly left Britain. The local Britons then formed their own kingdoms. The area around Chester was part of the kingdom of Powys. Chester is thought to be the "Fort Legion" mentioned as one of the 28 cities of Britain in an old book called the History of the Britons.

Legend says that King Arthur fought a big battle against the Saxons at the "city of the legions." Later, in 616, a Saxon king named Æthelfrith of Northumbria defeated a Welsh army at the Battle of Chester. This probably helped the Anglo-Saxons take control of the area.

The Anglo-Saxons called the city "Legeceaster," which later became "Ceaster," and finally "Chester." In 689, King Æthelred of Mercia started a church called the Minster of St John the Baptist. This later became the city's first cathedral.

In the 9th century, the body of St Werburgh was moved to Chester to protect it from Danish raiders. She was buried in a church that later became the current Chester Cathedral. A street in Chester, St Werburgh's Street, is still named after her.

The Saxons made the city walls stronger to protect against the Danes. The Danes occupied Chester for a short time. But King Alfred's daughter, Æthelflæd, rebuilt the Saxon fort and drove them out. In 907, she built a new church dedicated to St Peter.

An old record says that in 973, King Edgar came to Chester after his coronation. He held court near the River Dee. He supposedly took a boat up the river, and six or eight other "kings" rowed him! This showed that many smaller rulers accepted him as their king.

The Middle Ages: Norman Rule and Trade

After the Norman Conquest in 1066, the Normans took control of Chester. They destroyed 200 houses in the city. Hugh d'Avranches, a nephew of William the Conqueror, became the first Norman Earl of Chester. He built a castle near the river, which is now Chester Castle. It was rebuilt in stone in 1245.

The Earls of Chester had a lot of power. They controlled huge hunting forests. One earl, Ranulf I, even turned the farmlands of the Wirral into a hunting forest. Another earl, Ranulf II, helped capture King Stephen in 1140 and ended up controlling a third of England!

The independence of Chester under these earls was officially confirmed in 1398. The earls are remembered today with their shields on the suspension bridge over the River Dee.

In 1092, the first earl started a large Benedictine monastery dedicated to Saint Werburgh. This monastery was later closed by Henry VIII in 1540. It was then renamed and became Chester Cathedral.

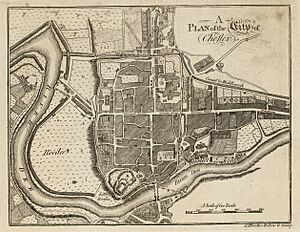

There's a popular story that the silting (when mud and sand build up) of the River Dee created the land where Chester's racecourse (called the Roodee) is now. However, the Roodee existed as early as the 13th and 14th centuries. The silting that shaped the Roodee as we see it today happened later, from the late 1500s onwards. This is shown by old maps and archaeological findings. For example, the 14th-century Water Tower, which is part of the city walls, was originally built out into the river. This shows how much the river has changed.

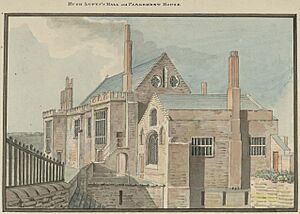

The weir (a low dam) above the Old Dee Bridge was not built by the Romans. It was built by Hugh Lupus, the Earl of Chester, between 1077 and 1101. Its purpose was to keep the water level high for his river mills. One of these mills led to the traditional song "Miller of Dee." The weir also stops salty tidal water from entering the fresh water of the Dee.

Chester's port became very busy under Norman rule. In 1195, a monk wrote that "ships from Aquitaine, Spain, Ireland and Germany unload their cargoes of wine and other merchandise." Chester was one of only five English ports that imported wine. In the 13th century, Chester was famous for its fur trade. Even in the mid-1500s, the port imported huge amounts of fur and skins.

However, the river estuary (where the river meets the sea) was silting up. This meant that large trading ships had to dock further downstream at places like Neston, Parkgate, and Hoylake.

Chester's first known mayor was William the Clerk. Mayors in early Chester often held their position for many years.

Tudor and Stuart Times: War and Change

In September 1642, tensions were rising between King Charles I and Parliament. It looked like a civil war might start. King Charles visited Chester and made sure a mayor who supported him, William Ince, was elected. In March 1643, a leading Chester Royalist, Francis Gamull, was asked to raise an army to defend the city. Outer defenses were built around Chester, including ditches, mud walls, and gun platforms.

Parliamentary forces then began to surround Chester. In September 1645, they took over the eastern defenses and reached the city walls. They set up cannons and fired at the walls. On September 22, a cannon battery in St John's churchyard made a 25-foot wide hole in the city walls near the Roman amphitheater. The defenders quickly filled the hole with woolpacks and featherbeds to stop the attack. You can still see the repairs to the wall today.

On the evening of September 23, 1645, King Charles I entered Chester with 600 men. He stayed at Sir Francis Gamull's house. Meanwhile, a Parliamentarian army was close by.

The next morning, September 24, 1645, the Battle of Rowton Heath took place. This battle happened on moorland southeast of Chester. Parliamentary forces defeated the Royalist army. The Royalists were trying to lift the siege of Chester and join with Scottish allies, but they were stopped by the Parliamentarians.

The battle lasted all day. It was mainly fought on horseback, with musketeers supporting the cavalry. King Charles I watched the fighting from Chester's Phoenix Tower on the city walls. He then moved to the Cathedral tower, but even there, a captain standing next to him was shot by musket fire from the victorious Parliamentarians.

About 600 Royalists died in the battle, including Lord Bernard Stuart, the king's cousin, and William Lawes, a famous English composer. Today, there is a small memorial to the battle in the village of Rowton.

The next day, the king left Chester. He told the city to hold out for 10 more days.

By 1646, after refusing to surrender nine times, and with the citizens starving, a treaty was signed. The city's mills and waterworks were destroyed. Even though there was a treaty, the Puritan forces destroyed religious symbols in the city, including the high cross. In 1646, King Charles I was declared a traitor next to this cross.

Things got worse. The starved citizens then suffered from the plague. From the summer of 1647 to the following spring, 2,099 people died.

In 1643, Sir Richard Grosvenor was allowed to enclose the Row in front of his house. After the war, other people on the street also enclosed their Rows. This is why Lower Bridge Street lost its Rows, except for a small trace at number 11.

Most of Chester was rebuilt after the Civil War. Many beautiful half-timbered houses from this time are still standing today.

Chester's port continued to decline. Most ships from the colonies now went to Liverpool. However, Chester was still the main port for passengers traveling to Ireland until the early 19th century. A new port was set up on the Wirral called Parkgate, but it also eventually fell out of use.

Georgian and Victorian Eras: A New Beginning

The port of Chester seriously declined from 1762 onwards. By 1840, it couldn't compete with Liverpool anymore. This wasn't mainly because of the silting of the River Dee, as once thought. It was because ships became much larger. These big ocean-going ships needed deeper water, so trade moved to Liverpool and other places on the River Mersey.

In the Georgian era, Chester became a wealthy town again. Rich families lived in elegant houses there. This continued during the Industrial Revolution. People from the upper classes moved to Chester to escape the busy, industrial areas of Manchester and Liverpool.

Edmund Halley (famous for Halley's Comet) worked at Chester Castle for a short time. In 1697, he recorded a one-inch hailstones falling in the area.

The Industrial Revolution brought the Chester Canal (now part of the Shropshire Union Canal) to the city. It was called "England's first unsuccessful canal" because it didn't bring heavy industry to Chester. Railways also arrived, with two large stations, though only one remains today.

A sad event happened during the building of the railway to Holyhead. A cast iron bridge over the River Dee near the racecourse collapsed. This was the Dee bridge disaster. It shocked the whole country because many other bridges were built with a similar design. Robert Stephenson, the engineer, faced a lot of criticism. The design was faulty, and many other bridges had to be taken down or replaced.

A leadworks was built by the canal in 1799. Its shot tower, used for making lead shot during the Napoleonic Wars, is the oldest remaining shot tower in the UK.

The beautiful Gothic Revival Town Hall was opened in 1869 by the Prince of Wales. It was designed by an Irish architect, William Henry Lynn. Along with the Cathedral, it still stands out in the city's skyline. The three clock faces were added in 1980.

The Eastgate clock was also built around this time. It's a central feature that crosses Eastgate street and is part of the city walls. This clock is very popular with tourists. It's even called the second most photographed clock in the UK, after Big Ben!

See also

- Chester

- List of people from Chester

- History of Cheshire

- History of England

- De laude Cestrie

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |