History of Czechoslovakia (1918–1938) facts for kids

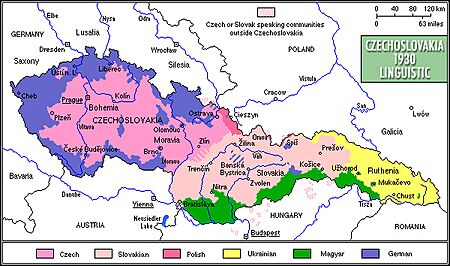

The First Czechoslovak Republic was a new country formed in October 1918. It came about after the big Austro-Hungarian Empire broke apart. This new nation was mostly home to Czechs and Slovaks. But it also included many other groups, like Germans (who made up about 23% of the people), Hungarians (about 5.5%), and Ruthenians (about 3.4%).

The country started with a good government where people could vote and a strong economy. However, in the 1930s, the world's economy got worse. This led to more arguments between the different groups of people living in Czechoslovakia. The biggest problem was between the Czech and German populations. This was made worse by the rise of Nazism in nearby Germany. Eventually, parts of Czechoslovakia were lost because of the Munich Agreement in 1938, which led to the end of the First Republic.

Becoming an Independent Country

After an agreement called the Pittsburgh Agreement in May 1918, the Czechoslovak declaration of independence was written in Washington. Important leaders like Tomáš Masaryk, Milan Rastislav Štefánik, and Edvard Beneš signed it in Paris on October 18, 1918. It was officially announced in Prague on October 28.

A new group called the National Assembly took charge in Czechoslovakia on November 14, 1918. At first, it was hard to know exactly where the country's borders would be, and it was impossible to hold proper elections. So, the first National Assembly was put together using results from older elections. People from Slovakia were added too. However, groups like the Germans and Hungarians were not included.

Around this time, on November 12, 1918, a new country called the Republic of German Austria was declared. It wanted to join Germany. This new state claimed all the German-speaking areas from the old empire, including those in Czechoslovakia.

The National Assembly of Czechoslovakia chose Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk as its first president. They also picked a temporary government led by Karel Kramář and started writing a temporary constitution.

In January 1919, a big meeting called the Paris Peace Conference took place. The Czech leaders, Kramář and Beneš, went to represent their new country. The conference agreed to create the First Czechoslovak Republic. This new country would include the historic lands of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia, along with Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia. Adding Ruthenia meant Czechoslovakia shared a border with Romania, which was an important friend against Hungary.

There were some arguments about the borders, especially regarding areas where many Germans lived. Some people, like the British, thought these areas should not be part of Czechoslovakia. However, the borders were decided without asking the people living there what they wanted.

In March 1919, there were reports of problems between Austria and Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovakia claimed Austria and a German state called Saxony were planning to attack. The main disagreement was over German-speaking parts of Bohemia and Moravia, later known as the Sudetenland. The German people there wanted to join Austria or Germany. But Czechoslovakia wanted to keep these areas because they had valuable mines. Czech troops were sent into these areas, and there were reports of clashes.

In January 1920, the Czechoslovak army moved into a region called Trans-Olza, which had many Polish people. This went against earlier agreements with Poland. After some fighting, a truce was made, and Czechoslovakia took control of areas west of the Olza River.

On September 10, 1919, Czechoslovakia signed an agreement called the Minorities Treaty. This treaty promised to protect the rights of all the different ethnic groups living in the country.

Building the New Country

The Constitution of 1920 set up a parliamentary system where people voted for their representatives. This meant many different political parties could form, and no single party was much stronger than the others.

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk was elected the country's first president in 1920. His leadership helped keep the country united. A group of five main Czechoslovak parties, known as the "Pětka" (The Five), worked together to form the government and keep things stable. Prime Minister Antonín Švehla led this group for most of the 1920s. Masaryk was re-elected in 1925 and 1929. He served as president until December 14, 1935, when he resigned because of poor health. Edvard Beneš took over as president.

Beneš had been Czechoslovakia's foreign minister from 1918 to 1935. He created a system of alliances that guided the country's international relations until 1938. Beneš was a democratic leader who looked to Western countries for ideas. He strongly believed in the League of Nations to keep peace and protect new countries. He also formed the Little Entente in 1921, an alliance with Yugoslavia and Romania. This was to protect against Hungary wanting to regain lost lands or the old royal family returning to power.

The leaders of Czechoslovakia had to find ways for the many different cultures to live together peacefully. From 1928 to 1940, Czechoslovakia was divided into four "lands": Bohemia, Moravia-Silesia, Slovakia, and Carpathian Ruthenia. Even though these lands had their own local assemblies, their power was limited. They mostly helped to adapt central government laws to local needs.

Special protection was given to national minorities. In areas where a minority group made up at least 20% of the population, they could freely use their language in daily life, in schools, and when dealing with government officials. German political parties even joined the government starting in 1926. Hungarian parties, however, never joined the government because they wanted Hungary to get back some of its old territories.

Growing Problems

Because Czechoslovakia had a very central government, people from non-Czech groups started to feel more nationalistic. Many parties and movements formed, wanting more political freedom for their regions. An example is the Hlinka's Slovak People's Party led by Andrej Hlinka.

When the German dictator Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, people in Central Europe became very worried about Germany attacking. President Beneš continued to focus on alliances with Western countries like France. He also sought an alliance with the Soviet Union. In 1935, the Soviet Union signed treaties with France and Czechoslovakia. These treaties said that the Soviet Union would help Czechoslovakia, but only if France helped first. Hitler himself later said he wanted to take over Bohemia and Austria. He even vaguely mentioned getting rid of two million Czechs and eventually the whole Czech nation.

There was a large German minority in Czechoslovakia, mostly living in a region called Sudetenland. These Germans demanded more freedom within Czechoslovakia. They claimed the government was treating them unfairly. A new political party, the Sudeten German Party (SdP), led by Konrad Henlein, pushed for these demands. This party was funded by the Nazis. In the 1935 elections, the SdP had a big success, getting over two-thirds of the votes from Sudeten Germans. This made relations between Germany and Czechoslovakia much worse.

Hitler met with Henlein in March 1938 and told him to make demands that the Czechoslovak government could not accept. On April 24, the SdP presented its demands, asking for self-rule for the Sudetenland and the right to follow Nazi ideas. If these demands were met, the Sudetenland could then join Nazi Germany.

On September 17, 1938, Adolf Hitler ordered the creation of the Sudetendeutsches Freikorps. This was a military-like group that took over from an organization of ethnic Germans in Czechoslovakia. The Czechoslovak government had shut down that group the day before because it was involved in many violent acts. The German government secretly helped, trained, and armed this new group. They then carried out attacks across the border into Czechoslovakia. Because of these actions, Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš and the government later considered September 17, 1938, as the start of an undeclared war between Germany and Czechoslovakia. The Czech Constitutional Court also agrees with this view today.

|

See also

- Germans in Czechoslovakia (1918–1938)

- Poles in Czechoslovakia

- Ruthenians and Ukrainians in Czechoslovakia (1918–1938)

- Slovaks in Czechoslovakia (1918–1938)

- Hungarians in Czechoslovakia (Slovakia)