History of Taranto facts for kids

The city of Taranto started as a Greek colony called Taras around 706 BC. It grew to be a powerful trading city-state in Magna Graecia (Greater Greece), which was the name for the Greek areas in southern Italy. Taranto controlled many other Greek colonies in the region.

Contents

Ancient Greek Times

How Taranto Began

Taranto was founded in 706 BC by people from Sparta, a famous Greek city. These founders were called Partheniae. They were the sons of unmarried Spartan women and free men who were not full citizens. The Spartans had allowed these unions to get more soldiers during a big war, but later they made the sons leave.

A legend says that the leader of the Partheniae, Phalanthus, asked an oracle (a wise person who could see the future) where to build a city. The oracle gave a strange answer: he should build it where rain fell from a clear sky. Phalanthus struggled to find such a place. One day, his wife was comforting him, and her tears fell on his forehead. Her name meant "clear sky," and Phalanthus finally understood the oracle! He found the perfect spot in Apulia, which is now Taranto's harbor.

The Partheniae built the city and named it Taras after the son of the Greek sea god, Poseidon. The symbol of Taranto, even today, is Taras riding a dolphin. At first, Taranto was ruled by a king, like Sparta.

Growing Strong and Facing Challenges

Taranto wanted to expand, but local tribes in Apulia resisted. In 472 BC, Taranto teamed up with another Greek city, Rhegion, to fight the Iapygian tribes. But their armies were badly defeated. Later, in 466 BC, Taranto lost to the Iapygians again. So many noble people died that the city changed its government from a rule by nobles to a democracy (where people vote).

Even as a democracy, Taranto stayed friends with its mother city, Sparta. During the Peloponnesian War, Taranto helped Sparta against Athens. Athens, in turn, supported the Messapians, who were enemies of Taranto.

In 432 BC, Taranto made peace with the Greek colony of Thurii. Both cities helped start a new colony called Heraclea, which soon came under Taranto's control. In 367 BC, powerful cities like Carthage and the Etruscans made a deal to stop Taranto's growing power in southern Italy.

Taranto reached its peak under the wise leader Archytas, who was a philosopher and mathematician. It became the most important city in Magna Graecia, a major trading port, and had a strong army and navy. But after Archytas died in 347 BC, the city slowly began to decline. Taranto's army was good, but it didn't have enough citizens to match the numbers of its enemies, like the Apulian tribes, Samnites, and later, the Romans.

Taranto often asked for help from other Greek cities against its neighbors. In 343 BC, it asked Sparta for help against the Brutian League. The Spartan king, Archidamus III, came to Italy but was killed in battle in 338 BC. Later, in 333 BC, Taranto called on Alexander Molossus, a king from Epirus, to fight the Bruttii, Samnites, and Lucanians. But he was also defeated and killed.

Wars Against Rome

First Fights

By the early 200s BC, Rome was becoming very powerful, and Taranto started to worry. Rome was building new towns in Apulia and Lucania. Some Greek cities in southern Italy even asked Rome for military help against their neighbors. For example, Thurii, which was under Taranto's influence, asked Rome for help in 282 BC. Taranto felt Rome was getting too involved in Greek affairs, which Taranto considered its own business. This led to a conflict.

There were two main groups in Taranto. The democrats, who were in charge, were against Rome because they knew Rome would take away their independence. The aristocrats, who had lost power, were more open to Rome, hoping it would help them regain influence.

Taranto had the strongest navy in Italy at the time. It had an agreement with Rome that Roman ships could not enter the Gulf of Taranto.

In 282 BC, Rome sent a fleet to help Thurii. Ten Roman ships were caught in a storm and ended up near Taranto during a religious festival. The Tarentines saw this as a hostile act, breaking their agreement. They attacked the Roman fleet, sinking four ships and capturing one.

After this, Taranto's army and navy went to Thurii. They helped the democrats there send the aristocrats into exile, and the Roman soldiers left Thurii.

The Pyrrhic War

Rome sent diplomats to Taranto, but the talks failed. The Roman ambassador was even insulted. So, Rome declared war on Taranto. Taranto decided to ask for help from King Pyrrhus of Epirus, a famous Greek general. In 281 BC, Roman soldiers attacked Taranto and took its treasures. Taranto, with help from other tribes, lost a battle against the Romans.

Pyrrhus agreed to help Taranto because they had helped him before. He also knew he could get help from other tribes in Italy. His big dream was to conquer Macedon, but he needed money. He planned to help Taranto, then go to Sicily to fight Carthage. If he won, he would have enough money to build a strong army and conquer Macedon.

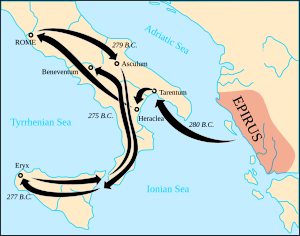

Pyrrhus arrived in Italy in 280 BC with a large army, including 20 war elephants. The Romans had a huge army too. Pyrrhus fought the Romans at the Battle of Heraclea. He won, but he lost many soldiers. He thought the Roman army would be easy to beat, but they were much stronger than he expected. Also, Rome could quickly replace its lost soldiers, while Pyrrhus was far from home.

Pyrrhus then marched towards Rome, hoping to get people to join him, but he didn't succeed and had to go back to Apulia.

In 279 BC, Pyrrhus defeated another Roman army at the Battle of Asculum. Again, he lost many of his best soldiers and officers. He couldn't easily get new soldiers, and his allies were not very reliable. The Romans, however, kept getting stronger. At this point, Greek colonies in Sicily asked Pyrrhus to help them fight Carthage. So, he left Italy for Sicily, leaving a small group of soldiers in Taranto.

The Tarentines called Pyrrhus back in 276 BC. The war against Rome started again. But this time, Pyrrhus was defeated by the Romans at the Battle of Beneventum. He decided to give up his fight in Italy. After six years, Pyrrhus returned to Epirus, leaving only a small group of soldiers in Taranto.

The Romans finally captured Taranto in 272 BC. They destroyed the city's walls. Thirty thousand Greek people were sold as slaves, and many valuable artworks were taken to Rome.

Second Punic War

During the Second Punic War, Rome kept a strong army in Taranto because they feared the city might join Hannibal, their enemy. Some Tarentine hostages in Rome tried to escape and were executed, which made people in Taranto even more anti-Roman. In 212 BC, some people in Taranto who supported Carthage helped Hannibal enter the city. However, Hannibal couldn't capture the city's main fort, which was defended by Roman troops. This meant he couldn't use Taranto as a major port for his invasion of Italy.

The city supported Hannibal against Rome. But in 209 BC, a commander from the Bruttii tribe betrayed the city to the Romans. The Romans then attacked, killing many people, including the Bruttians who had helped them. Thirty thousand Greek people were sold as slaves again. Taranto's art treasures, including a statue of Victory, were taken to Rome.

Roman Republic and Empire

Even in ancient times, Taranto was known for its pleasant weather. Famous people from Taranto included poets, a painter named Zeuxis, and the mathematician Archytas.

In 122 BC, a Roman town called Neptunia was built next to Taranto. It was named after the Roman sea god, Neptune, whom the Tarentines worshipped. This Roman town was separate from the Greek city at first. But later, in 89 BC, Taranto became a Roman municipium (a self-governing town), and the two areas joined.

In 37 BC, important Roman leaders like Marcus Antonius, Octavianus, and Lepidus signed a treaty in Taranto. This extended their shared rule (the second triumvirate) until 33 BC.

Taranto had its own local law, called Lex municipii Tarenti. Parts of this law, written on bronze plates, were found in 1894.

During the late Republic and the entire Roman Empire, Taranto was just a regular city in a Roman province. The city's population decreased over time. Emperor Trajanus tried to help by giving land in Taranto to his retired soldiers, but it didn't work. Taranto's story followed the rest of Italy during the late Empire, facing attacks from groups like the Visigoths and being ruled by the Ostrogoths.

Middle Ages: Changing Rulers

Byzantine and Lombard Control

After the Gothic wars, the Byzantine Empire (the eastern Roman Empire) took control of Taranto in 540. They ruled it until the Lombards (a Germanic people) from the Duchy of Benevento captured it in 662.

In 663, the Byzantine Emperor Constans II came to Taranto with his army and defeated the Lombards. He then conquered Apulia and visited Rome.

After the Emperor left, the Byzantines and Lombards fought again. The Lombards eventually took Taranto and Brindisi from the Byzantines in 686.

In the 8th century, Muslim groups from North Africa, called Saracens, began raiding Taranto and southern Italy. This threat lasted for many centuries.

Arab Rule

In the early 800s, internal fights weakened the Lombard rulers. In 840, the Saracens took control of Taranto, taking advantage of the weak Lombard government. Taranto became an Arab stronghold and a busy port for 40 years. From here, ships full of prisoners sailed to Arab ports, where the prisoners were sold as slaves. In the same year, an Arab fleet from Taranto defeated a Venetian fleet and raided cities along the Adriatic Sea.

Taranto was used as a base for many Arab raids into other parts of Italy. This worried the Byzantine Emperor Basil I, who decided to fight the Arabs and take back Taranto.

In 880, two Byzantine armies and a fleet recaptured Taranto from the Arabs, ending their 40-year rule. The Byzantines brought in Greek settlers to increase the population. Taranto became an important city in the Byzantine area of southern Italy. However, in 882, the Saracens captured it again for a short time.

Back Under Byzantine Rule

In 928, a Saracen fleet attacked Taranto, taking all the remaining people as slaves and sending them to North Africa. Taranto was empty until the Byzantines took it back in 967. The Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus II Phocas understood how important Taranto was for military control in southern Italy. He rebuilt the city, added strong defenses, and made it a key point against the rising Norman power. But the local Byzantine government was weak, and Taranto faced more Saracen raids. In 977, Saracens attacked again, taking prisoners and burning parts of the city.

Norman Conquest

The 11th century saw a fierce struggle between the Normans and the Byzantines for control of Taranto and other lands. In May 1060, the Norman leader Robert Guiscard conquered the city. But in October, the Byzantine army took it back. After three years, in 1063, a Norman count entered Taranto, but he had to flee when a Byzantine admiral arrived. Taranto was finally conquered by the Normans. In 1071, the Normans appointed the first Norman archbishop for Taranto.

Principality of Taranto (1088-1465)

Taranto became the capital of a Norman principality (a territory ruled by a prince). The first ruler was Bohemond of Taranto, son of Robert Guiscard. He received Taranto and most of the heel of Apulia as his share of his father's lands. For 377 years, the Principality of Taranto was sometimes a powerful, almost independent area within the Kingdom of Sicily (and later Naples). Other times, it was just a title given to the heir to the crown or to the husband of a queen.

Ferdinand I of Naples eventually united the Principality of Taranto with the Kingdom of Naples after his wife, Isabella of Taranto, died. The principality ended, but the kings of Naples continued to give the title "Prince of Taranto" to their sons.

From Renaissance to Napoleon

In March 1502, the Spanish fleet of King Ferdinand II of Aragon, who was allied with Louis XII of France, captured Taranto's port and the city.

In 1570, Admiral Giovanni Andrea Doria brought his fleet to Taranto's Mar Grande (Big Sea) for repairs. The famous writer Miguel de Cervantes was with this fleet. This fleet later joined other Christian forces and defeated the Turkish fleet at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. Some nobles from Taranto also fought in this battle.

In 1647, a revolt in Naples spread to Taranto. The city also joined the short-lived Parthenopaean Republic in 1799.

In 1746, Taranto had about 11,526 people, all living on the small island. In 1765, a local nobleman started the Mysteries of the Holy Week celebrations, which are now the most important event in Taranto.

After a defeat of Ferdinand IV of Naples, the French general Jean-de-dieu Soult occupied Taranto and other areas in 1801. Napoleon wanted to build a strong fort in Taranto to put pressure on the British base in Malta. On April 23, 1801, 6,000 French soldiers entered Taranto and fortified it. The French presence and defensive works helped Taranto's economy. A famous French officer, the novelist Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, who was an expert in fortifications, died in Taranto in 1803.

In 1806, Napoleon made Taranto a special hereditary dukedom in the Kingdom of Naples.

When Napoleon fell and Joachim Murat was defeated, southern Italy and Taranto returned to the rule of the Bourbon family, forming the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

Since Italian Unification

On September 9, 1860, Taranto became part of the temporary government created by Giuseppe Garibaldi after he conquered the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. The next year, all of southern Italy joined the Kingdom of Italy. At that time, Taranto had about 27,000 people.

Between May and June 1866, the new Italian navy, called the Regia Marina, gathered in Taranto's harbor. This was because Italy was about to declare war on Austria (Third Italian War of Independence).

During World War I, Taranto was an important base for the Italian navy. On August 2, 1916, the Italian battleship Leonardo da Vinci sank there, possibly due to sabotage.

On the night of November 11, 1940, during World War II, British naval forces severely damaged Italian ships anchored in Taranto in what became known as the Battle of Taranto.

British forces landed near the port on September 9, 1943, as part of the Allied invasion of Italy (Operation Slapstick).

See also

- Greek coinage of Italy and Sicily

- Archbishopric of Taranto

- Timeline of Taranto

Images for kids