History of education in Spain facts for kids

The history of education in Spain shows how schools and learning changed over time. It was shaped by political changes and new ideas in society. Education began in the Middle Ages, mostly for the clergy (church leaders) and nobles. Later, during the Renaissance, a growing middle class, called the bourgeoisie, started to lead the way. The Constitution of 1812 and the ideas of liberal thinkers helped create modern education in Spain.

Contents

- Early Education in Spain

- Education in the Middle Ages

- Education in the Modern Age

- Education in the Contemporary Age

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Education in Spain

The Romans brought their education system to Spain. Around 80 BC, a Roman leader named Sertorius started a special school in Osca (now Huesca). Here, the children of important local families learned Greek and Roman subjects. This helped them prepare for leadership roles later on.

Archaeologists have found remains of the "House of Hippolytus" in Complutum (Alcalá de Henares). This building, from the 3rd and 4th centuries, was a school for young people. It was connected to a powerful Roman family and used for both learning and fun.

Even after the Roman Empire declined, some education continued. However, it mostly became focused on Christian religious teachings, especially in monasteries. There might have also been a special school in Visigothic Toledo for high-ranking nobles, including some women.

Education in the Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages in Spain, three main religions existed: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim. Each had its own ways of educating people.

Christian education often happened in schools connected to cathedrals, called cathedral schools. These schools originally trained future priests. But because they were the only places to learn, they slowly started accepting other people too.

In the 13th century, King Alfonso VIII of Castile made the Palencia school a Estudio General (a type of early university) in 1212. King Alfonso IX of León likely founded the Estudio General de Salamanca in 1218. Later, King Alfonso X the Wise officially called it a "University" in 1253. This might make Salamanca the first place to use that title.

These early universities used cathedral buildings and rented spaces for classes. Special colleges were also created to prepare students for university exams. In Salamanca, the Colegio de Santa María de la Vega was founded in 1166. In 1401, Bishop Diego de Anaya started the first Colegio Mayor (major college), called San Bartolomé. This college helped poor but smart students by giving them scholarships for tuition, food, and housing.

Universities offered degrees like Bachelor, Licentiate, Master, and Doctor. The way they were run was quite democratic. The rector, who was like the head of the university, was elected by students and professors for one year. Students had special privileges, and the university even had its own police and prison!

Education in the Modern Age

This period covers the 16th and 17th centuries. At first, universities were somewhat fair, helping many poor students. However, over time, studying at certain prestigious colleges became very popular. This led to noble students taking over these colleges and universities. They used tricks, like demanding proof of "cleanliness of blood" (meaning no Jewish or Muslim ancestors), which only noble families could easily provide.

In the late 1400s and early 1500s, Spanish education was shaped by humanism. This was a movement that focused on human values and classical studies. The Catholic Monarchs encouraged humanism in their court.

Humanist Education

Education for Nobles

Princes and other royal children, along with kids from important families, studied in special "royal classrooms." They learned from the best humanist teachers. Many books were written to guide future rulers. Their education included physical training like jumping, javelin throwing, and sword fighting. They also studied classical writers and history. While they read ancient texts, they were also taught to admire saints and God. Good manners and diplomatic skills were also important.

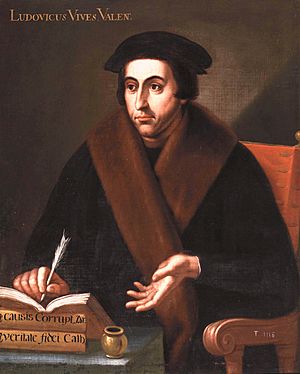

Girls from noble families also received special attention. People realized that educating women was important for keeping religious and moral values strong. Juan Luis Vives wrote a famous book in 1523 called On the Instruction of Christian Women. It stressed the importance of religious reading for girls.

Education for the Middle Class

In the Modern Age, the oldest son in a family usually inherited everything. So, younger sons often went to colleges or universities to find a career. Even poorer nobles, called hidalgos, attended. University education was a way to improve one's social standing and gain respect. Kings needed educated people for government jobs. The most important universities were Salamanca, Alcalá de Henares, and Valladolid. Students studied theology, law, and medicine. Latin and the liberal arts were also taught.

However, humanist ideas became less popular during the 17th century.

Education for Society

Since the Middle Ages, there was an effort to help smart people, even if they were poor. Bishop Diego de Anaya founded the Colegio Mayor de San Bartolomé in Salamanca in 1401. It offered scholarships to poor boys. Other wealthy people also created schools for this purpose. However, by the 17th century, these colleges became so prestigious that wealthier students started taking the places meant for the poor.

Most other people in society could not read or write. They learned mostly by listening or by seeing images from the Catholic Church. However, literacy slowly increased in the 1500s. Religious groups and local governments started "first letters" schools. These taught reading, writing, numbers, and catechism (religious instruction). Children also learned trades and some reading/writing by working for artisans in guilds. Some teachers, often priests or university students, also taught pupils at home.

In the 17th century, education faced challenges due to a lack of organization. But it was also when teachers started getting paid by town councils. Their work and hours became regulated, and they began using textbooks. Teachers also formed their own groups to control who could teach and protect their interests. The government did not have a clear plan for children's education. Many children had to leave school early to work and help their families.

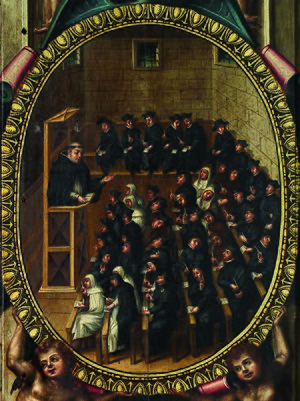

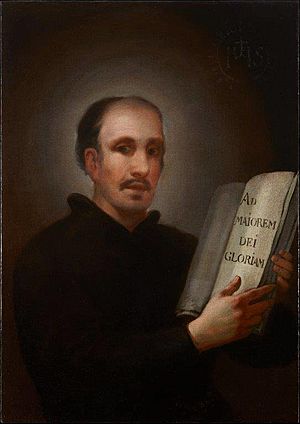

The Jesuits and Education

The Society of Jesus (Jesuits) was a religious order founded by Ignatius of Loyola in 1534. At first, they didn't plan to teach. But they started offering theology and philosophy classes, which were free. This meant that children from wealthy families, as well as humble young people, could attend and learn to read. The College of Gandía was the first Jesuit school to offer classes and accept outside students. Many more Jesuit colleges were founded for teaching throughout the 16th century.

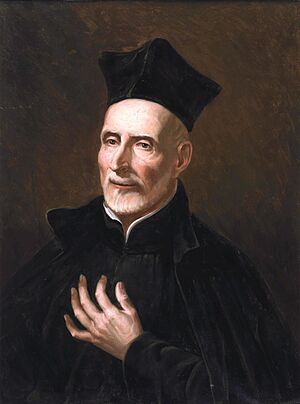

The Piarists and Free Schools

The Order of the Pious Schools, founded by Saint Joseph Calasanz (1557–1648), brought free public schools to Europe in the 17th century. These schools were open to everyone, especially the poorest children. The first Piarist schools in Spain opened in the late 1600s. By the 18th century, there was a huge demand for Piarist schools, but many requests could not be met. Calasanz's teaching style focused on helping the poor, being effective and innovative, and combining "Piety and Letters" (which means "Culture and Faith"). After him, many other religious groups also started schools dedicated to education.

The Enlightenment and Education

When the Bourbon family came to power in Spain, they brought new ideas from the Enlightenment. However, these ideas didn't change education much until the government of Charles III. His reforms included expelling the Jesuits, changing universities and colleges, and making education less controlled by the Church.

First Steps in Basic Education

In the 18th century, people realized that many Spaniards could not read or write. This was seen as a problem for progress. So, the government started taking steps to train teachers and open schools. In 1780, the Colegio Académico del Noble Arte de Primeras Letras was created to train teachers. Important thinkers like Pedro Rodríguez de Campomanes and Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos wrote about new teaching methods and the need for better public schools. They believed that a state could not be wise, rich, or powerful without good education.

University Reforms

Spanish universities were slow to adopt new scientific and philosophical ideas. Their old, medieval teaching methods were seen as outdated. The government tried to reform them with the Plan of Studies of the University of Salamanca in 1771. This plan aimed to change how universities were run and what they taught. However, students and professors resisted these changes, and the reforms were not very successful.

After the Jesuits were expelled in 1767, the Reales Estudios de San Isidro de Madrid were founded for secondary education. Teachers there were chosen based on their skills, not by religious orders. They taught subjects like Fine Arts, Mathematics, Physics, and Greek. Other important institutions founded during this time included medical colleges and royal academies for arts and sciences.

Education in the Contemporary Age

The Cortes of Cadiz (1812)

The Constitution of 1812 was very important for education. It said that "first letters" schools (basic education) should be set up everywhere. It also called for more "instruction establishments" and a "competent number of universities." The government was tasked with overseeing public education. The Constitution even set a deadline: by 1830, all citizens who wanted to vote had to know how to read and write.

In 1813, a plan for national education, known as the Quintana Report, was created. It later became law during a period of liberal rule.

Ferdinand VII's Rule

When King Ferdinand VII returned to power, he brought back absolute rule. This meant the Catholic Church regained its strong role in education. Private schools were shut down because they were seen as "poisoning the youth" with foreign ideas. Universities were also changed. Many professors were removed, and teaching became more focused on traditional religious views. Modern science was even removed from the curriculum.

Primary schools were also regulated. Boys learned Christian doctrine, reading, writing, and basic math. Girls learned Christian doctrine, reading, and "work proper to their sex," like knitting and sewing. Teachers had to prove their "cleanliness of blood" (meaning no Jewish or Muslim ancestors). To prevent revolutionary ideas, universities were closed for a few years in the early 1830s.

Isabella II's Reign

The 19th century was a time of political unrest in Spain, and education was affected. Different governments introduced various laws. The Pidal Plan of 1845 aimed for "freedom, gratuity, centralization, inspection and uniformity" in education. However, it didn't last long.

The Concordat of 1851 (an agreement with the Catholic Church) stated that all education, from universities to schools, must follow Catholic doctrine.

The Moyano Law of 1857

The Public Instruction Law of 1857 was the first complete and organized education law in Spain. It aimed to tackle the serious problem of illiteracy. This law brought together many ideas that had been discussed for years. It created a stable education system that lasted for over a hundred years.

The Moyano Law divided education into three levels:

- First Education: Taught in schools and was free for children whose parents couldn't pay.

- Secondary Education: Taught in secondary schools. Students earned a Bachelor of Arts degree, which was needed for higher education.

- University Education: Included Faculty Studies (like Philosophy, Law, Science, Medicine), Technical Education, and Professional Education. Only studies done in public institutions were officially recognized.

This law emphasized:

- Free primary education (for those who needed it).

- Central control over education.

- Uniformity (the same system everywhere).

- Secularization (less direct church control, though still influenced by Catholicism).

- Limited freedom of education (private schools had to meet certain requirements).

The law also had some unfair rules for women. Their education was not seen as important, and specific subjects were created just for them. Teaching was often the only suitable job for educated women.

In 1865, student protests against government interference in universities were harshly put down. This event, known as the Night of St. Daniel, resulted in deaths and injuries.

The Democratic Sexennium (1868-1874)

After the Revolution of 1868, the government focused on academic freedom. A decree in 1868 allowed teachers to choose their own teaching methods and textbooks. Both public and private schools had to have students take the same exams. Secondary education was reorganized, with more emphasis on Spanish language and new subjects like psychology and agriculture. The 1869 Constitution allowed anyone to open and run schools, with the government only checking for "hygiene" and "morality."

The Restoration (1874-1923)

Orovio's Circular and the Institución Libre de Enseñanza

At the start of the Restoration period, the Minister of Public Works, the Marquis of Orovio, forced teachers to swear an oath not to teach anything against Catholicism. Many teachers, especially those with Krausist ideas (a philosophical movement), refused. They left the university and founded the Institución Libre de Enseñanza (Free Institution of Education) in 1876. This was a very important movement for educational reform, led by Francisco Giner de los Ríos.

Romanones' Decrees (1901)

In 1901, the Minister of Public Instruction, Count de Romanones, issued decrees to modernize secondary and primary education. The Secondary Education Decree aimed to create "General and Technical Institutes" offering many subjects. It set a six-year curriculum for the bachelor's degree with seven or eight subjects per year. It also limited class sizes and regulated teacher salaries.

The Primary Education Decree aimed to improve basic schooling. Romanones believed that the state should pay teachers' salaries and that this reform was a "national aspiration."

Board for the Extension of Studies and the Student Residence

In 1907, the Board for the Extension of Studies and Scientific Research was created. In 1910, the famous Student Residence (Residencia de Estudiantes) was established. These institutions aimed to promote science and culture.

The Second Republic (1931-1939)

The Second Republic brought major changes to education:

- Bilingualism: Recognized different languages like Catalan. Teaching could be in the mother tongue up to age 8.

- Religious Education: Made religious teaching optional, based on religious freedom. Schools had to offer it, but it was taught by church-appointed teachers outside regular lessons.

- Pedagogical Missions: These groups traveled to rural areas to spread general culture, educational guidance, and civic education. They set up libraries, gave readings, and showed films.

- Focus on Primary Schools: The Republic aimed to build 27,000 new schools to educate one million children who didn't attend school. However, due to economic problems, this goal was not fully met.

Lorenzo Luzuriaga drafted a new education law based on these principles:

- Public Education: Should be a main job of the State. Private schools were allowed if they didn't have political goals.

- Secular Education: Public schools should not teach religion as a compulsory subject.

- Free Education: Especially at the primary level.

- Active Learning: Education should be creative and ongoing, with training for teachers.

- Social Focus: Schools should be connected to society and parents.

- Coeducation: Boys and girls should be educated together with the same curriculum at all levels.

- Unified System: Education had three levels: Primary (4-12 years), Secondary (12-18 years), and University.

- Teacher Preparation: Teachers needed to be well-prepared and believe in the new educational goals.

The Second Republic had two main periods:

Progressive Biennium (1931-1933)

During this time, many educational changes happened. Adult education was regulated. The Pedagogy section was created at the University of Madrid. Inspectors for primary and secondary education were given more independence and a technical-pedagogical role. The Law on Religious Denominations and Congregations removed teaching functions from the Church.

Conservative Biennium (1934-1936)

A shift in government led to an "educational counter-reform."

- Coeducation was banned in primary schools, meaning boys and girls had to study separately.

- The Central Inspectorate of Education was abolished.

- Student representation in university governing bodies was removed.

Franco's Regime (1939-1975)

Education Laws (1938-1953)

During and after the Civil War, new education laws were passed. The Law for the Reform of Secondary Education (1938) and the Law on the Organization of Spanish Universities (1943) were introduced.

The Law on Primary Education of 1945 reflected the ideas of Franco's regime, which was based on national-Catholic thinking. Education was seen as a right of the family, the Church, and the State. It was compulsory, free, and required the separation of boys and girls. The Spanish language was compulsory everywhere. Primary education was for ages six to twelve and taught in national, Church, or private schools.

The Law on the Organization of Secondary Education of 1953 also followed these ideas. Students had to pass an entrance exam for secondary education. There were different types of baccalaureate (high school) programs, including a preparatory course for university.

General Education Act of 1970

The General Education Law of 1970 was a major reform. It aimed to create a fairer and more efficient education system. It covered all levels of education and focused on unity and flexibility.

The structure of education became:

- Nursery Education: (2-4 years old), voluntary.

- Pre-school Education: (4-6 years old), voluntary, preparing for reading, writing, and math.

- General Basic Education (Educación General Básica, EGB): (6-14 years old), compulsory and free. It had eight grades divided into three cycles. Students could get a High School Diploma (Graduado Escolar) to continue studies or a Completion Certificate for Compulsory Education.

- Unified Polyvalent Baccalaureate (Bachillerato Unificado Polivalente, BUP): (14-17 years old), three courses. After this, students took a University Orientation Course (COU) to prepare for university entrance exams.

- Professional Education: For students who wanted job qualifications. It had two levels, leading to Auxiliary Technician or Specialist Technician titles.

- Special Education: For students with special needs, this law greatly boosted support for them.

- Adult Education and Distance Education were also expanded.

- Higher Education: At universities, with three levels: Diploma, Bachelor's Degree (or Engineering/Architecture), and Doctorate.

This law introduced modern teaching methods, like continuous assessment. It was the first law since Moyano's to regulate the entire education system. It created a common basic education, integrated vocational training, and improved the teaching profession. It also helped achieve full schooling for all Spaniards at compulsory levels.

Education in Democracy (1978-Present)

Constitution of 1978

The Constitution of 1978 established the right to education and freedom of education. It made basic education compulsory and free. It also allowed for both public and private schools to receive government funding. Parents were given the right to choose the religious and moral education for their children. This meant that "Catholic Religion" became an optional subject in schools.

Key Education Laws

Since 1978, several important laws have shaped Spanish education:

- Organic Law regulating the Statute of Educational Establishments (LOECE) (1980): This law regulated schools but was partly changed by the Constitutional Court.

- University Reform Law (LRU) (1983): The first major update to university laws since Franco's time.

- Organic Law regulating the Right to Education (LODE) (1985): This law focused on how schools were run, promoting democratic management and participation from the educational community.

- Organic Law on the General Organisation of the Spanish Education System (LOGSE) (1990): This law extended compulsory education from age 14 to 16. It introduced Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO) and emphasized concepts like attention to diversity and education in values.

- Organic Law on the Quality of Education (LOCE) (2002): This law was mostly not put into practice because the government changed soon after.

- Organic Law on Education (LOE) (2006): Another important education law.

- Organic Law for the Improvement of the Quality of Education (LOMCE) (2013): This law aimed to improve the quality of education.

- Organic Law for the Modification of the LOE (LOMLOE) (2020): This is the current education law in Spain (as of 2024).

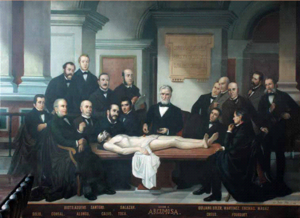

Images for kids

-

Orla (graduation photo) of the 1940–1941 academic year at the Zaragoza medical school.

-

Photograph of José Ibáñez Martín (1944), who was Minister of Education during Franco's regime.

-

The end of the 1812 Constitution by Ferdinand VII. His return to absolute rule meant education went backwards.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la educación en España para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la educación en España para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |