History of salt facts for kids

Salt, also known as table salt, is a special chemical compound called sodium chloride (NaCl). It's made of two tiny parts: sodium and chloride. All living things need salt to survive!

Humans have used salt for thousands of years. It was super important for keeping food fresh, especially before refrigerators existed. This helped early civilizations grow because people could store food and move it over long distances. Because salt was so hard to find, it was a very valuable item for trading. Some societies, like ancient Rome, even used it as a form of money! The word "salary" might even come from the idea of Roman soldiers being paid in salt, though historians still discuss this. Many "salt roads," like the Via Salaria in Italy, were built way back in the Bronze Age to transport salt.

Throughout history, having salt was key for civilizations. In Britain, some town names ending in "-wich," like Northwich, show they were once places where salt was found. The Natron Valley in Egypt was very important because it provided a type of salt called natron to the powerful Egyptian Empire. Today, salt is easy to find, cheap, and often has iodine added to it, which is good for your health.

Contents

History of Salt

Salt in Ancient Times

People started making salt very early, around 6,000 BCE, in places like Romania.

Solnitsata, which is thought to be the oldest town in Europe, was built around a salt-making site. This town in Bulgaria likely became rich by selling salt to other areas.

Salt was highly valued by many ancient groups, including the Greeks, Tamils, Chinese, and Hittites. As the city of Rome grew, roads were built to make it easier to bring salt to the capital. The Via Salaria (meaning "Salt Road") went from Rome to the Adriatic Sea. The Adriatic Sea was saltier and better for making salt than the sea closer to Rome.

During the later Roman Empire and the Middle Ages, salt remained a valuable product. It was carried along "salt roads" to Germanic tribes. Long lines of camels, sometimes forty thousand strong, traveled hundreds of miles across the Sahara desert to bring salt to markets in Africa. In China, salt was important for new inventions and provided a lot of money for the government.

Cities and Salt Wars

Salt played a big role in where important cities grew and how powerful they became. For example, Liverpool in England became a major port because it exported salt from the large Cheshire salt mines.

Salt also made cities and even whole countries rich. Poland is a great example, with its famous salt mines in Wieliczka and Bochnia. These mines once provided a third of the country's income! Salt mining there started in the 1200s and continued until 1964.

Cities along salt roads often charged high taxes on salt passing through their lands. This even led to the creation of new cities, like Munich in 1158.

The gabelle, a very unpopular salt tax in France, lasted from 1286 to 1790. This tax made salt so expensive that it caused people to move away, attracted invaders, and even led to wars.

In American history, salt was important in wars. During the American Revolutionary War, British supporters tried to stop American soldiers from getting salt to preserve their food. Before Lewis and Clark explored the Louisiana Territory, President Thomas Jefferson even mentioned a huge "mountain of salt" as a reason for their journey.

During the movement for India's independence, Mahatma Gandhi led the Salt Satyagraha protest. This was a famous protest against the British tax on salt in India.

Salt Production in England

People were making salt in England very early. Evidence of salt production from as far back as 3766–3647 BCE has been found in Yorkshire. Salt was made from both mines and the sea in Medieval England. The open-pan salt making method was used along the coast, where salty water was heated in large, shallow pans.

The words "wich" and "wych" in English place names often mean there was a salty spring or well there. By the 11th century, these names were linked to places that specialized in salt production. Several English towns are famous for their salt history, including the four "Cheshire wiches": Middlewich, Nantwich, Northwich, and Leftwich, as well as Droitwich in Worcestershire. These towns were so important that they were mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086, showing how vital salt was to the economy.

Salt Trade

In imperial China, the government controlled salt production and trade. This was a main way for them to earn money for centuries.

In more recent times, it became more profitable to sell salted food, like fish, than just pure salt. So, places that had lots of fish, like the British-controlled cod fisheries in North America, worked closely with salt makers.

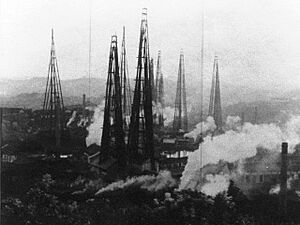

The search for oil in the late 1800s and early 1900s actually used the same methods and technology that salt miners had developed. They even looked for oil in places where large salt deposits were found underground.

How Salt is Made

On a large scale, salt is made in two main ways: by letting salty water (brine) evaporate, or by mining it from underground. Evaporation can happen using the sun's heat or with special heating machines.

Solar Evaporation from Seawater

In places with lots of sunshine and not much rain, people can make salt by letting seawater evaporate using the sun. Salty water is moved through a series of connected ponds. As the water evaporates, the salt becomes more and more concentrated. In the last pond, the salt crystals form and settle on the bottom.

Open Pan Production from Brine

One traditional way to make salt in cooler climates is using open pans. In this method, salty water is heated in large, shallow open pans. The earliest pans were made of ceramic or lead. Later, iron pans were used, and people started using coal instead of wood to heat the brine. As the water boiled away, salt crystals would form. Workers would rake out the salt, and more salty water would be added.

Closed Pan Production Under Vacuum

Today, the old open-pan method has mostly been replaced by a closed system. In this system, the salty water is evaporated in a sealed container under a partial vacuum. This makes the water boil at a lower temperature, saving energy.

Salt Mines

In the late 1800s, new mining and drilling methods made it possible to find and dig up more salt from deeper underground. This increased the amount of mined salt available. Even though mining salt was often more expensive than getting it from evaporating seawater, this new source helped lower the price of salt because it broke up monopolies. Mining salt is still very common today. For example, a company in Middlewich, UK, produces a lot of the salt used for cooking in the country.

Salt from Ashes

In the Visayas Islands of the Philippines, there's a traditional way to make salt called asín tibuok. People soak coconut husks or driftwood in seawater for months. Then, they burn these materials into ash. Seawater is poured through the ashes to create a very salty liquid. This liquid is then heated until the salt forms. Sometimes, coconut milk is added before heating. This traditional method is becoming rare because it's hard to compete with cheap, factory-made salt.

Other Uses for Salt

The Chinese were among the first to write down different kinds of salt, how to use them, and how to get them, around 2700 BCE. The ancient Greek doctor Hippocrates suggested using salt water to help heal sick people by having them bathe in the sea. Later, in 1753, an English doctor named Richard Russell wrote a book about the uses of seawater. He said salt was a "common defense against corruption" and helped with many cures.

In Ethiopia, blocks of salt called amoleh were cut from salt flats. These blocks were carried by camels to highland areas and then traded throughout the rest of Ethiopia. These salt blocks were even used as a form of money!

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la sal para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la sal para niños

- Alberger process

- Bath salts

- Cerro de la Sal (Salt Mountain), Peru

- Fish sauce

- Garum

- Illinois Salines

- International Salt Co. v. United States

- Iodised salt

- James Ford (pirate)

- Joy Morton

- John Crenshaw

- Lüneburg Saltworks

- Mineral lick (salt lick)

- Morton Salt

- Red hill (salt making)

- Saltern

- Salt evaporation pond

- Salt in Cheshire

- Salt industry in Ghana

- Salt in the American Civil War

- Salt March (India)

- Salt Riot (Moscow uprising of 1648)

- Seawater greenhouse

- Anikey Stroganov (Solvychegodsk and Perm salterns)

- Sülze Saltworks

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |